Is Your Brain Really Being 'Eroded' by AI?

![]() 07/10 2025

07/10 2025

![]() 584

584

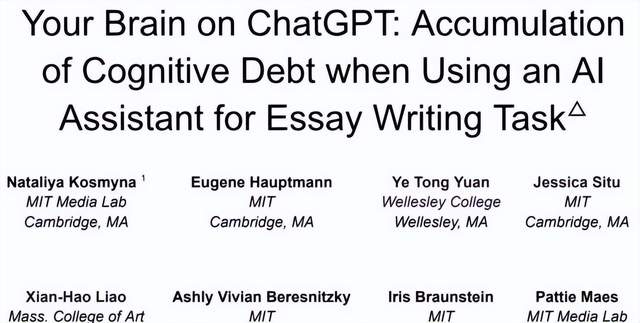

Recently, an MIT research report titled 'Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt when Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task' has sparked considerable controversy.

Numerous media outlets have reported that the 216-page study directly implies that AI usage may degrade brain function, leading to headlines such as 'ChatGPT Shrinks the Brain by 47%', causing widespread anxiety among AI users.

However, a careful reading of the 206-page report reveals that media interpretations have significantly deviated from the core findings, simplifying complex scientific research into stark, black-and-white assertions.

In fact, MIT's research does not support the simplistic notion that 'using AI makes people dumber.'

The study delves much deeper and broader than what the media has portrayed.

Let's first briefly introduce MIT's study, 'Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt when Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task.'

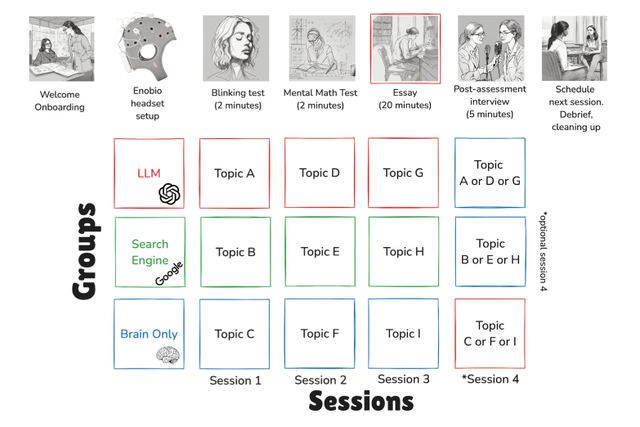

The study divided 54 participants into three groups for writing tests: a purely manual group relying solely on their own knowledge, a search engine group using Google, and an AI-assisted group using ChatGPT.

Over a four-month period, college students in these three groups were required to complete four rounds of writing tests, equivalent in difficulty to SAT-level essays. Each test lasted 20 minutes, with intervals of 1-2 weeks between tests.

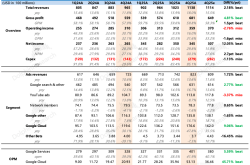

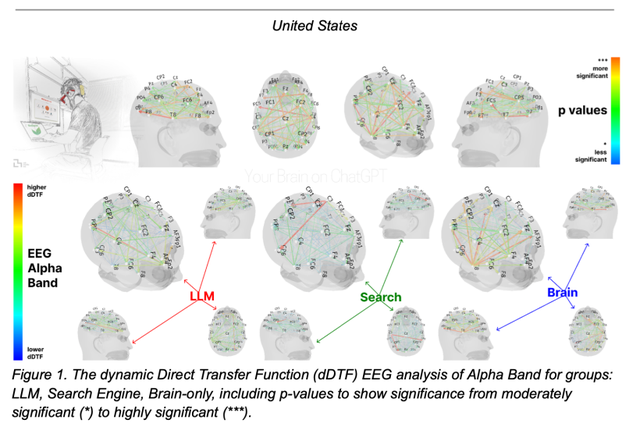

MIT's EEG monitoring revealed that in the first three rounds of writing tests, the purely manual group exhibited the most extensive neural network connections in the brain, involving multiple brain regions working in concert during tasks such as memory retrieval and logical integration. The search engine group showed moderate brain activity, relying on visual information management and screening abilities, but still requiring autonomous knowledge integration. The AI-assisted group showed significantly reduced brain activity, with neural connections decreasing by 45%-55% compared to the purely manual group, and 83.3% of AI users were unable to recall content they had created just minutes earlier.

In the fourth round of cross-testing, when the AI-assisted group wrote independently, their brain activity increased but remained significantly lower than that of the purely manual group. Conversely, when the purely manual group used AI for the first time, their brain activity did not decrease but increased, and the quality of their output was superior to that of participants who relied on AI.

MIT's experiments demonstrate that the negative effects of AI are not irreversible but that long-term unconscious reliance on AI may lead to cognitive debt. Therefore, researchers encourage a mindset of independent thinking before using AI.

However, some media outlets have exaggerated MIT's research conclusions during dissemination.

First, there is a misinterpretation of concepts. Some reports claim 'brain atrophy by 47%', but MIT's study measured changes in neural connection activity, not physical atrophy of brain structure. The study found that participants who relied on ChatGPT for writing had a reduction of about 47% in neural coupling strength during tasks compared to the purely manual group. This does not mean brain 'degeneration' but indicates that under AI assistance, certain cognitive regions of the brain are less active during specific tasks.

Second, there is confusion in logical relationships. Cognitive debt is not irreversible intellectual decline. The concept of 'cognitive debt' refers to the possibility that short-term reliance on AI may weaken long-term cognitive abilities, similar to the idea of 'use it or lose it.' However, this effect depends on the manner of use. The study found that when the purely manual group used AI for the first time, their brain activity increased, and the quality of their output was superior to that of participants who relied on AI. Conversely, the AI-dependent experimental group showed a significant decline in performance when separated from the tool.

Finally, the research conclusions were simplified crudely. The study did not negate the value of AI. MIT's paper clearly states that AI can be a cognitive enhancement tool, but only if users maintain active thinking. When individuals with high baseline cognitive abilities use AI, neural connections actually strengthen, and only those who rely on ChatGPT long-term experience temporary laziness in brain activity.

Upon reading the report, we find that not only did MIT's study not directly conclude that 'AI erodes the brain,' but its research design also has limitations. We need to understand its conclusions more objectively and cautiously.

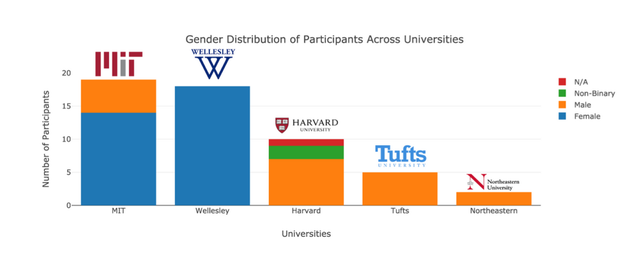

1. Limited sample representativeness. The number of participants was relatively small, with 54 initially and only 18 completing the fourth stage. These individuals were from top academic institutions in the Boston area, belonging to the typical WEIRD sample (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic), with cognitive habits, educational backgrounds, and technological literacy above average. Conclusions drawn from this specific group cannot be directly generalized to a broader, more diverse audience.

2. Experimental settings differ from real-world environments. Completing a SAT-style philosophy essay in 20 minutes is a highly structured task. Equating the results of this single, high-pressure, time-limited task with a decline in overall cognitive ability simplifies reality. In real-world scenarios, people's interactions with AI are nonlinear and multi-step, allowing more time for reflection and adjustment. This difference may exaggerate the negative effects observed in the study.

3. Inaccurate measurement tools. EEG technology has high temporal resolution, capturing instantaneous changes in thinking, but low spatial resolution, unable to detect deep structures like the hippocampus, crucial for long-term memory formation. Moreover, EEG signals are susceptible to external interference such as environmental electrical noise, potentially affecting the accuracy of results. The researchers themselves acknowledged this in the paper and suggested that future studies should use techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to obtain a more comprehensive picture of brain activity.

4. Correlation does not equal causation. The decrease in neural connections can be interpreted not only as laziness but also as 'cognitive offloading.' Reduced brain activity may indicate that the brain outsources formatted, low-level cognitive tasks such as information retrieval to AI, freeing up valuable cognitive resources for higher-level strategic planning and critical research. The current experimental design cannot fully distinguish between these two distinct cognitive modes.

In short, short-term, small-sample studies cannot yield universally applicable conclusions. To derive the media-disseminated conclusion that 'AI leads to cognitive decline' requires more rigorous, longitudinal studies over a longer period.

Meanwhile, some studies have concluded that 'AI tools contribute to human brain cognitive activities,' further supporting the notion that 'using AI does not cause brain degeneration.'

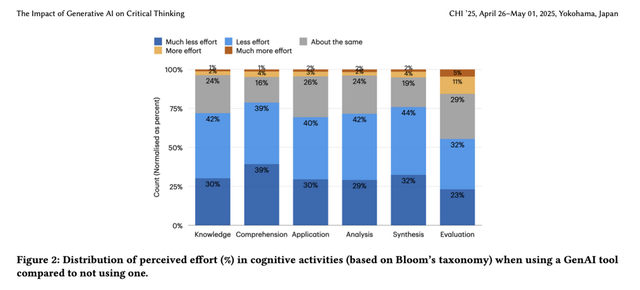

In February 2025, a study from Microsoft Research and Carnegie Mellon University titled 'The Impact of Generative AI on Critical Thinking: Self-Reported Reductions in Cognitive Effort and Confidence Effects From a Survey of Knowledge Workers' found that when users are confident in their professional abilities in a field, using AI actually stimulates more critical thinking.

A systematic review published in the journal 'Computers & Education,' titled 'Higher-order thinking skills-oriented problem-based learning interventions in mathematics: A systematic literature review,' analyzed 69 related experimental studies from 2022 to 2024. It showed that using ChatGPT can enhance students' critical thinking, problem-solving, and creative thinking abilities in higher-order thinking training. The study emphasized that AI-assisted problem-based learning (PBL) can help students engage in conceptual integration and logical reasoning more effectively.

These empirical studies convey that we need to move beyond the simplistic binary opposition of 'AI is harmful or beneficial' and instead consider more fundamental questions:

How can we use AI to make ourselves better?

Historically, every technological revolution has sparked fears of human capability degradation. The ancient Greek philosopher Socrates feared that writing would impair human memory, and the book 'Amusing Ourselves to Death' warned that television leads to the decline of linear logical thinking. McLuhan pointed out that computer systems might completely paralyze our central nervous system.

However, writing, television, and computers have not made us dumber; instead, they have enhanced our skills.

Writing indeed changed the way we remember but did not eliminate our memory abilities, creating more complex knowledge systems and preserving valuable human civilization. Television, while altering information reception patterns, cultivated new visual thinking abilities, enriching our understanding of the world. Computers have not paralyzed our nervous systems but vastly expanded human cognitive boundaries, turning the world into a miniature global village.

The media's view that 'AI makes people dumber' often implies a technological determinism fallacy, ignoring human agency in technology use.

It is undeniable that the brain, like a muscle, grows stronger with use and weakens with disuse. When writing independently, the brain undergoes deep cognitive processing, including 'conception, language organization, expression, and revision.' When using AI, one only engages in the most superficial prompt input without considering the logic and context behind the answers.

However, AI's impact on cognition is not unidirectional degradation or enhancement but highly dependent on usage patterns and educational design. Just as some use computers to learn courses from around the world, others become addicted to games, leading to psychological issues. The key lies in how we use technology.

If individuals indiscriminately, passively, and comprehensively rely on AI to complete all cognitive tasks, their ability to independently solve complex problems, engage in deep logical thinking, produce original work, and retain effective memories may substantially decline in the long run.

However, the degree to which AI affects thinking varies by individual and usage. Those who actively use AI as an auxiliary tool rather than a complete replacement, maintain critical thinking during use, and consciously engage in cognitive exercise and deep participation may experience fewer negative effects and even leverage AI to enhance their cognitive efficiency and creativity.

If we can maintain critical thinking and the habit of deep memory writing while using AI for brainstorming, AI will not make us dumber but rather serve as a more intelligent search engine assistant.

Therefore, revisiting MIT's research report, we find that it aims to convey:

Technology is neutral, and its impact depends on its application.

To prevent addiction, the next time you're about to ask AI a question, ask yourself, 'How would I solve this problem if AI didn't exist?'

Perhaps, the answer lies within your own brain.