China's Autonomous Driving Revolution: Beyond Baidu, Embracing a Dynamic Data Network

![]() 08/07 2025

08/07 2025

![]() 553

553

When Baidu announced its partnership with Lyft to venture into Europe, and German media hailed it as "China's autonomous driving technology going global," a profound question arose: Who truly epitomizes China's autonomous driving prowess?

The answer isn't confined to Baidu alone. It lies in the -30°C icy roads of Harbin, the "ant colony algorithm"-like electric vehicle traffic in Guangzhou, and the synaptic connections of 1,600 smart intersections in Yizhuang. China's autonomous driving future is a symphony, not a solo, orchestrated by a super data network that seamlessly integrates vehicle-end perception with roadside intelligence. Baidu does not embody China's autonomous driving; it's a chaotic yet layered battle of innovation.

Equating Baidu with China's autonomous driving landscape is akin to using the Forbidden City to represent all of Chinese architecture, overlooking the diverse ecosystem spanning 9.6 million square kilometers.

Among the initial batch of demonstration licenses for intelligent connected vehicles issued in Shanghai, Luobo Kuaipao is but one player among Volkswagen, Pony.ai, Chery, CIIC Auto, UDI, Qiangsheng, and Jinjiang. The high cost is another challenge; the sixth-generation driverless car's hardware expenses amount to millions. When Wuhan claimed "break-even," Baidu's free cash flow plummeted to -8.9 billion yuan. This isn't a sustainable business model; it's a capital-intensive marathon. The capital market's response is even more blunt: WeRide secured investment from Yutong Heavy Duty Vehicles, while GAC invested 500 million yuan to establish a driverless vehicle subsidiary. This decentralization underscores that China's autonomous driving isn't a "Baidu vs. the world" narrative but a collective breakthrough by thousands of players across various fields.

Luobo Kuaipao's limitations are evident. During morning rush hour in Wuhan, it struggled amidst a sea of electric vehicles, prompting honking from frustrated drivers, earning it the moniker "slow Luobo." The hardware cost of its sixth-generation driverless car nears a million, keeping operational costs per kilometer high, while Baidu's free cash flow in Q1 2025 dropped to -8.9 billion yuan. A business model reliant on continuous capital injections from its parent company cannot claim to represent China.

China's true strength lies in more pragmatic endeavors: JD Logistics' unmanned delivery vehicles have achieved a commercial closed loop in Suzhou, Mogu Auto's RoboBus has safely traversed over 2 million kilometers, and even BYD equips its 70,000-yuan Seagull electric car with L2-level assisted driving, feeding algorithms with 20 million kilometers of real-world road test data daily. This comprehensive "from ports to townships" penetration is the genuine essence of China's autonomous driving.

Data War: Cameras + Millimeter-Wave Radars Are Just the Beginning, Roadside Intelligence Is the Ultimate Testbed. Tesla's pure vision approach is incompatible with China not due to technological backwardness but because it underestimates the "complexity of road conditions" here.

From the mixed traffic of motor and non-motor vehicles in Yunnan townships to Chongqing's "Akina-style" mountain city curves, from icy Harbin roads to rain-flooded Chengdu streets, China's roads offer the world's most extensive "stress test set." Relying solely on vehicle-end cameras + millimeter-wave radars is like using a stethoscope to examine an elephant—you can't grasp the whole picture.

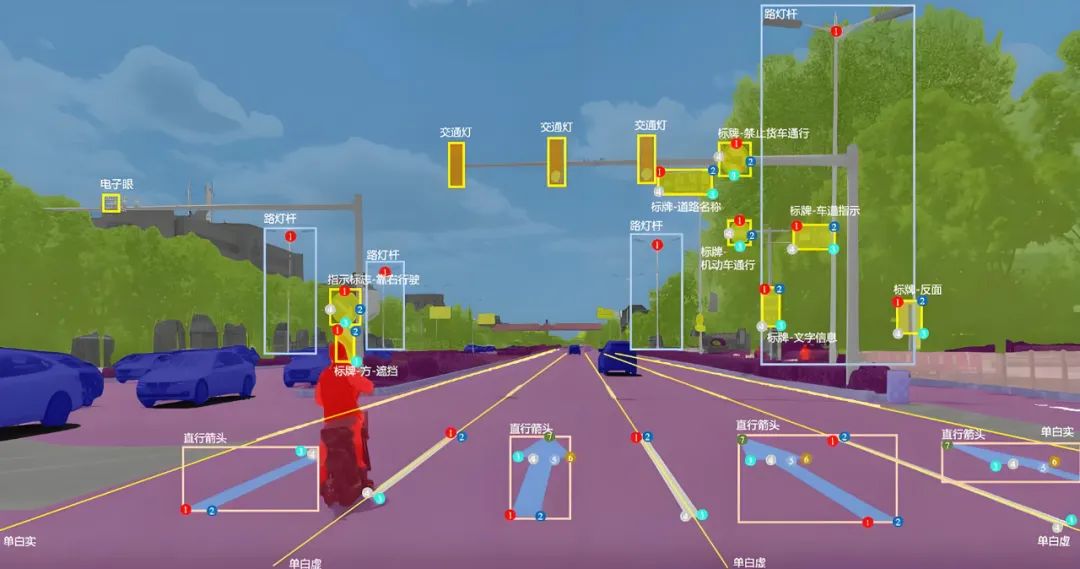

The real breakthrough lies in roadside intelligence's 24/7 ultra-visual perception capabilities. Beijing Yizhuang's "cloud control platform" proves this: 1,600 smart intersections are synaptically connected to vehicles, and traffic lights automatically adjust timing based on traffic flow, revolutionizing from "vehicles seeing lights" to "lights seeing vehicles." Roadside intelligence isn't at odds with vehicle-end perception; it's an extension—the vehicle end handles "immediate concerns," while the roadside provides the "distant poetry and fields."

Research on the Impromptu VLA dataset is even more straightforward: When an autonomous driving system encounters unstructured scenarios like temporary traffic police direction or blurred road boundaries, relying solely on vehicle-end sensors can lead to "decision paralysis." Roadside equipment offers a global perspective, such as early warning of sudden road conditions 500 meters ahead, precisely China's "vehicle-road coordination" route's core advantage.

Technical routes aren't binary; they have levels. Vehicle-road-cloud is the inevitable evolution of single-vehicle intelligence. The debate on "single-vehicle intelligence vs. vehicle-road coordination" mirrors "standalone mobile phone mode vs. mobile internet"—the former is destined to be overshadowed by the latter.

Volkswagen is betting on vehicle-road coordination, and Huawei pursues vehicle-road-cloud integration, not to negate single-vehicle intelligence but because its ceiling is obvious. Waymo achieves L4 deployment after 32 million kilometers in closed scenarios, but any random Chinese county town's road complexity surpasses American suburbs. Relying solely on vehicle-end computing power and algorithms is insufficient.

Data speaks volumes: Huawei's ADS, installed in 500,000 vehicles for "nationwide drivability," relies on roadside equipment data. Xpeng's XNGP covers 243 cities, bolstered by targeted data collection for Chinese scenarios. Even after Tesla's FSD enters China, it must adjust algorithms to adapt to local scenarios like "electric vehicles suddenly crossing"—this isn't a route debate but a consensus that "single-vehicle intelligence must embrace roadside data."

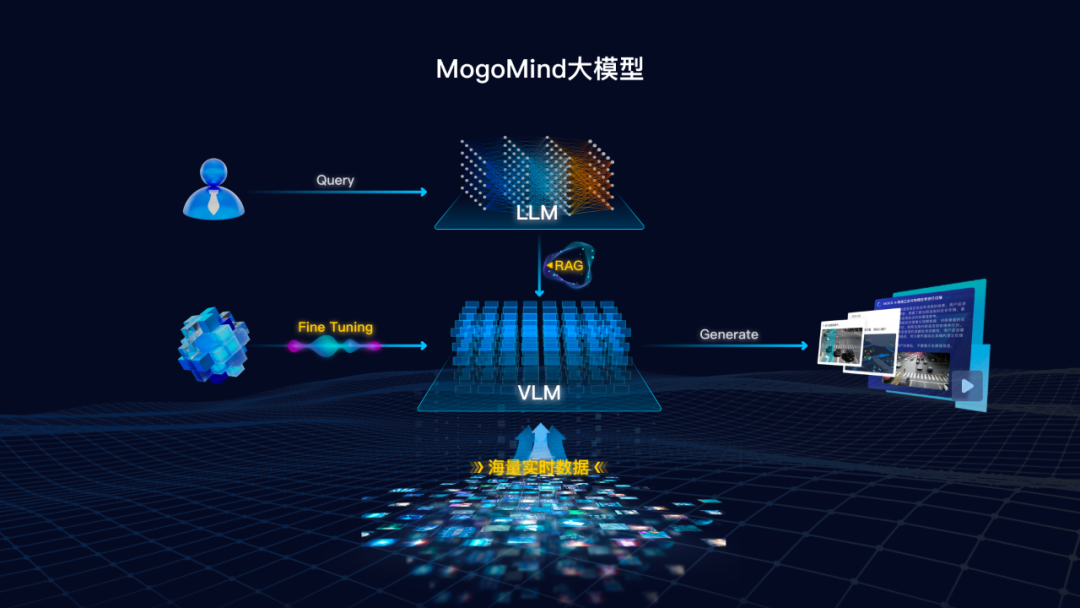

While Luobo Kuaipao grapples with intersection decision optimization, Mogu Auto has integrated its MogoMind AI large model with dynamic real-time data, achieving global perception, deep cognition, and real-time reasoning and decision-making. Roadside perception's contribution is soaring.

Robotaxi is a capital game; Robobus meets rigid livelihood demands. The Robotaxi model, favored by companies like Baidu, resembles a money-burning "technological showcase," while the true commercialization key lies in Robobus.

Behind Luobo Kuaipao's 1.4 million orders is a nearly million-yuan hardware cost per vehicle and a rigid monthly expenditure of 12,000 yuan for safety personnel. Wuhan's average order price is less than 1.5 times that of online car-hailing but costs three times more. This "subsidy-for-data" model is unsustainable. Goldman Sachs predicts China's Robotaxi market will grow 757 times over ten years to $47 billion, but this long-term gain requires astronomical funds, and how long can Baidu's cash flow sustain it?

In contrast, Robobus, in closed scenarios like parks, scenic areas, and bus lanes, doesn't need to handle complex road conditions but can directly replace traditional buses, reducing costs per kilometer to less than 1 yuan. Suzhou's unmanned buses have operated for three years with an average of 300 orders per day and zero accidents—this "small steps, quick progress" commercialization approach is more reliable than Robotaxi's "big strides forward."

JD Logistics' unmanned delivery vehicles and Yangshan Port's unmanned container trucks prove that instead of striving for L4 on open roads, it's better to earn money first in limited scenarios. Robobus is the ideal vehicle for this logic.

The answer to China's autonomous driving is inscribed in the data soil.

When discussing China's autonomous driving, we should focus not on which company has entered Europe but on the "data neural network" spanning 9.6 million square kilometers—vehicle-end cameras capturing real-time road conditions, millimeter-wave radars penetrating heavy rain and fog, roadside lidars scanning the overall situation, and cloud brains scheduling in real-time.

Baidu and Luobo Kuaipao are players in this revolution but not its definers. China's autonomous driving essence lies in Huawei's ADS vehicle-road-cloud coordination, Mogu Auto's physical AI large model, Xpeng's localized data, JD's scenario closed loop, and thousands of companies' deep cultivation in their respective fields.

Ultimately, what can pass China's ultimate road condition test isn't a single "elite car" equipped with lidars but a super data network perceiving ice, rain, and electric vehicle traffic—this is China's unique answer to the autonomous driving industry.