OpenAI's Annual Revenue Hits $140 Billion: Why Is Domestic AI Still Unprofitable?

![]() 08/14 2025

08/14 2025

![]() 563

563

Over the past year, Meta's actions in AI have bordered on the extraordinary: spending billions to acquire a 49% stake in Scale AI, investing hundreds of millions of dollars to poach talent and strengthen its team, and appointing the 26-year-old Alexandr Wang as Meta's first "Chief AI Officer."

According to this year's forecasts, Meta's capital expenditure intensity has soared to a staggering 35% of revenue. This means that for every $100 of revenue, $35 is invested in AI, essentially wagering a substantial portion of the company's assets.

Three other US companies are also "betting big on AI" like Meta: Microsoft, Google, and Amazon.

Based on the financial forecasts released by these four tech giants, their AI-related capital expenditures this year will reach an astonishing $400 billion, primarily invested in AI infrastructure construction.

This figure surpasses the entire EU's defense expenditure for the entire year of 2023 and is significantly outpacing us.

Even considering unlisted companies such as ByteDance, along with the AI capital expenditures of operators undertaking basic tasks, estimates by CICC suggest that domestic AI's overall capital expenditures will not exceed RMB 500 billion by 2025.

Many attribute the gap between the two to a "computing power bottleneck." However, the root of the problem is not just the lack of GPUs but rather the absence of a sufficiently clear business logic that can support trillion-level investments.

The US has swiftly identified this logic.

From a data perspective, the speed at which AI generates revenue in the US is accelerating rapidly. The annualized revenue of OpenAI+Anthropic will exceed $29 billion by the end of this year, and investment banks predict that this figure may rise to $60-$100 billion by the end of 2026. AI applications led by startups are also thriving on both the consumer (C-end) and enterprise (B-end) sides.

In contrast, domestic AI commercialization has yet to find a suitable answer. Even for products like Keling AI that have emerged, more than 70% of their revenue comes from overseas.

More concerning, amidst geopolitical uncertainties, AI innovations originally born in China are accelerating their "spillover." Companies such as Manus, Lovart, and Heygen are either relocating their headquarters to Singapore or the US, or simply establishing companies overseas.

These relocation moves are not merely to be "closer to overseas markets"; the deeper reason lies in the fact that the difficult-to-navigate domestic commercial path is lowering the expected return on capital expenditures.

In the global technology competition, domestic technology companies are facing increasing structural barriers. Even if we set aside the chip restrictions, if the path to AI commercialization is not navigated soon, the return on capital expenditures will be difficult to establish. And once the return rate continues to decline, the gap between us and the US in the AI race will only widen.

Making a lot of noise but not making money may be the biggest hidden worry behind the apparent "prosperity" of our AI industry.

/ 01 / Global AI Is Making Money Faster and Faster

The speed at which AI generates revenue far exceeds everyone's imagination.

Over the past year, the most astonishing thing has not been the speed at which AI models are updated but rather the slope of commercial monetization they bring.

Let's first look at the top players:

At the end of last year, OpenAI's annualized revenue (ARR) was $5.5 billion, breaking through $10 billion in June this year. Recently, the New York Times revealed that its revenue has reached $12-$13 billion in annualized revenue and will reach $20 billion by the end of the year, with an increase of nearly 300%.

Anthropic's growth is even more impressive. Anthropic's ARR was only $1 billion last year, reaching $4 billion in the first half of this year, and is expected to exceed $9 billion by the end of the year, with a year-on-year surge of 800%.

That is, by the end of this year, the combined ARR of OpenAI+Anthropic will reach $29 billion. Investment banks predict that at this growth rate, this figure may climb to $60-$100 billion by the end of 2026.

What does this mean? Amazon's cloud computing business AWS had a full-year revenue of $107.6 billion last year—the two leading large model manufacturers have almost recreated an AWS in just three years.

And this explosion does not only exist at the basic model layer. On the application side, whether it is for consumers (C-end) or enterprises (B-end), the US AI market has produced astonishing revenue curves.

In the C-end market, startups represented by AI programming are starting to explode:

The ARR of the AI programming tool Agent Cursor, priced at $20 per month, has reached $500 million, attracting more than 360,000 users worldwide; the AI programming product Lovable achieved $10 million in revenue within 2 months and reached $100 million in ARR by the 8th month.

Even niche AI applications have impressive commercial performance.

Tolan, an AI companion app developed by Portola, has achieved an annual recurring revenue (ARR) of $12 million just a few months after its launch. The ARR of the AI video editing tool OpusClip has also reached $20 million.

The B-end market, on the other hand, has become the most important wealth creation machine for AI, giving rise to a batch of high-valuation, rapidly growing AI companies across various fields such as law, customer service, healthcare, and recruitment.

Glean (Search): Valuation of $7.2 billion, ARR of $100 million

Mercor (Recruitment): Valuation of $2 billion, ARR of $100 million

Crescendo (Customer Service): Valuation of $500 million, ARR of $91 million

Harvey (Legal): Valuation of $5 billion, ARR of $75 million

Clay (Sales): Valuation of $3 billion, ARR of $30 million

Abridge (Healthcare): Valuation of $2.75 billion, ARR of $100 million

The common characteristics of these companies are: they have been established for a short time, have extremely steep revenue slopes, rapid product penetration, and rising valuations. This speed is making many larger companies feel anxious.

The new consensus in Silicon Valley over the past year has been that "large companies can't compete with small companies." The reason is simple: these small companies are more agile, able to produce products that meet market demand in a very short time, and talent is more willing to go to innovative environments. More crucially, small companies can also obtain financing.

While the US AI market is surging along the path of commercialization, our AI market presents a completely different picture.

/ 02 / Technology Has Caught Up, But It's Still Hard to Make Money

Despite continuous breakthroughs at the technical level, the commercialization reality of our AI industry appears particularly bleak.

According to data from Hualong Securities, the total revenue of the AI application sector in the domestic computer industry in 2024 was RMB 76.8 billion, with a year-on-year increase of only 6.4%; the net profit attributable to shareholders was RMB 3.5 billion, with an increase of only 2.7%. By the first quarter of 2025, net profit had even fallen to less than RMB 30 million, essentially stagnating.

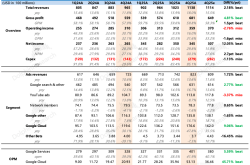

In contrast, US AI application companies have demonstrated a clear growth curve:

Taking nine companies such as Salesforce, Adobe, ServiceNow, and Palantir as examples, their combined revenue in Q1 2025 reached $23.6 billion, with a year-on-year increase of 12.1%, and an average operating profit margin of 15.8%.

Behind these data lies a fundamental difference in industrial structure:

US AI is experiencing a golden age of entrepreneurship where "small companies outperform large companies," giving rise to a large number of technology startups; while domestic AI is "dominated by large companies, with small companies running alongside," and mainstream products are almost entirely in the hands of platform enterprises.

For example, in the AI programming sector, the top domestic products come from ByteDance (Trae), Alibaba (Tongyi Lingma), and Baidu (Wenxin Kuama), with few independent startups standing out.

An even more serious problem is that even AI products that have emerged generally fall into the dilemma of "having traffic but no revenue."

According to QuestMobile data, as of March this year, the monthly active user count of domestic AI native apps has reached 270 million, even surpassing ChatGPT's 180 million. But there are very few products that have truly achieved large-scale monetization.

Even for Keling AI, which has an annual revenue exceeding $100 million, more than 70% of its revenue comes from overseas markets.

The payment dilemma is not only repeated on the C-end but also difficult to break through on the B-end. AI products in the To B market face similar problems as SaaS enterprises: small enterprises have no budget, and large enterprises rely on customization, with profits being repeatedly compressed.

On one end, user volume is insufficient, and on the other end, delivery costs are too high. A truly scalable and replicable business model has yet to emerge.

As a result, a large number of AI innovative products born in our country are flowing out.

In June this year, Manus announced that it would relocate its headquarters from China to Singapore and establish branches in the US and Japan. Of the original 120-person team in China, 40 core technical backbones relocated, and most of the rest were laid off. Prior to this, AI video company Heygen also relocated its headquarters from Shenzhen to Los Angeles. Lovart even directly established its headquarters in San Francisco.

This divergence in the commercialization of AI between China and the US is not accidental but rather a continuation of the path differences already laid down during the Internet era.

/ 03 / How Long Can the Logic of Entry Points Hold?

In August 2011, Marc Andreessen wrote the famous prophecy in the Wall Street Journal: "Software is eating the world," heralding the beginning of the mobile Internet era.

Since then, the Chinese and American Internet have taken two completely different paths.

In the US, "software" took over the wave of consumer-grade applications, driving a comprehensive explosion of SaaS startups. From 2010 to 2015, more than 1,000 new SaaS startups were added each year. During this period, venture capital investment gradually reached a peak, with amounts invested each year in the tens of billions of dollars, and most of this money flowed into the SaaS industry.

In China, however, it was the consumer Internet that truly changed the era.

ByteDance reshaped the global content distribution logic with information flow, while Pinduoduo emerged from the sinking market, bringing e-commerce into Amazon's backyard. Behind every success story is the rise of super apps and the control of traffic entry points. The domestic Internet narrative is one where traffic drives everything.

Borrowing the viewpoint from the public account "Platform Thinking," the difference between China and the US is not just in the service object they serve but rather in two underlying paradigms: China speaks of "entry points," while the US speaks of "interfaces."

In fact, we are not without enterprise software; most of it exists within the "closed-loop" ecosystems of large companies, serving as a doorstop for cloud computing sales. These software seemingly do business in enterprise services but have not yet escaped the shadow of the consumer Internet: relying on burning money to gain scale, using free products to stack users, and then relying on "traffic monetization" to replenish funds, continuing the typical "entry point" mindset.

And it is precisely this path dependence that constitutes the current divergence:

The problem is that AI is not a new application that can be installed in the App Store; it is a basic capability that "disrupts paths and compresses processes." In the world of AI, users no longer start from an app but rather from a problem or intention—directly heading towards the result.

The result is that the value of entry points is constantly being compressed: from a "path economy" to a "result economy," and the value of controlling user paths also depreciates.

This explains why AI commercialization is progressing faster in the US: SaaS companies originally operated with an "interface" mindset, and AI is merely a new capability plugin; whereas in China, an excessive reliance on the "traffic closed loop" approach makes it difficult for AI to quickly embed into existing products and organizational processes, resulting in an embarrassing situation where there is technology but no scenario, and users but no revenue.

The root of the problem lies not in technological backwardness but in rigid paths. What is truly alarming is not that we are temporarily behind the US but rather that we are still embracing an "interface world" with an "entry point mindset."

Although there are still some problems with the commercialization of the domestic AI industry, the outlook is not pessimistic.

There has never been only one standard answer for how technological waves land. Retail, e-commerce, short videos... In the past decade, every industrial leap in China has not followed the US path.

The same is true for AI. It may not overturn our "large company-dominated" industrial structure, but it will definitely force all players to shift from "controlling entry points" to "connecting interfaces":

Instead of competing for the starting point of traffic, it is better to become a pathway in the ecosystem; Instead of closing off user paths, it is better to amplify one's ability to be called upon.

This may be the true watershed for our AI industry towards commercialization.

Written by Lin Bai