OpenAI Courts the 'Trillion-Dollar Club', Ushering in AI Investment 2.0 Era

![]() 10/17 2025

10/17 2025

![]() 549

549

OpenAI is orchestrating a 'high-stakes game' involving the world's top tech companies, with trillion-dollar deals at stake.

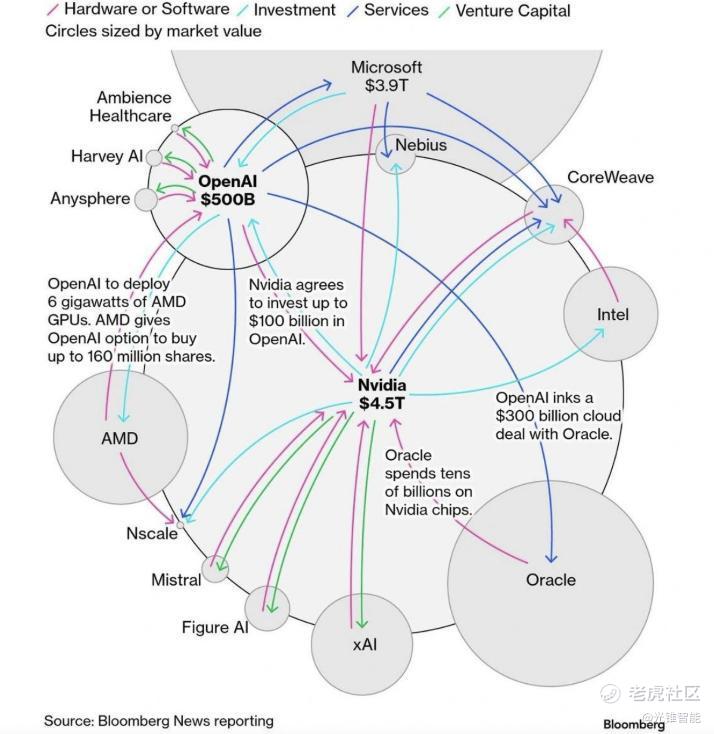

In just a few months of 2025, OpenAI has spearheaded a series of colossal orders with giants like NVIDIA, AMD, Oracle, and Broadcom, planning to launch large-scale AI infrastructure projects. On October 13, OpenAI secured another deal with Broadcom for AI chip deployment.

Amid OpenAI's 'frenetic ordering spree,' the market values of its partner companies have surged.

Oracle, in particular, has seen the most dramatic growth. With a $300 billion deal with OpenAI over the next five years, Oracle's stock price soared 36%, pushing its market value to nearly $1 trillion. AMD's market value also jumped nearly $70 billion in a single day following the partnership announcement.

Amid the flurry of AI investment deals, some have noticed OpenAI is forming a closed-loop value chain through orders for chips, data centers, and AI technology services. Players involved in OpenAI's partnerships are organizing a systematic AI construction alliance.

However, others argue that these orders carry significant risks. The expected returns on these AI investments largely hinge on OpenAI's long-term profitability. If AI-generated revenues and profits fall short, it could lead to severe 'value destruction.'

'We're going to spend big on infrastructure. We're taking this gamble—a company-wide bet that now is the right time to act.'

As OpenAI CEO Sam Altman emphasized in an October 9 interview, the recent flurry of collaborations between tech giants and OpenAI may reflect a new consensus emerging in the AI industry—

The days of 'playing it safe' are over; it's time to go 'all in' on AI.

01 The AI Investment 2.0 Phase Has Arrived

If one phrase could summarize the significance of OpenAI's deal with Oracle, it would be: This transaction shatters the 'comfort zone' of 'rational AI investment' that tech giants once enjoyed.

Previous AI investments were essentially a contest of disposable funds among tech giants.

Take Alibaba and Google as examples. Both have remained relatively conservative in their AI investments, maintaining a highly rational approach overall.

Here, we introduce the Capex (Capital Expenditure)/EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization) ratio as a reference. This metric reflects how much of a company's operating profit is allocated to capital investments.

According to Alibaba's latest quarterly report (as of June 30, 2025), its Capex stood at RMB 38.676 billion, with adjusted EBITDA at RMB 45.735 billion, resulting in a Capex/EBITDA ratio of 0.846.

For Google, referencing its parent company Alphabet's latest quarterly report (as of June 30, 2025), Capex (Purchases of property and equipment) reached $22.446 billion. Since Google does not disclose EBITDA, we approximate it by adding Operating Income ($31.271 billion) and Depreciation of property and equipment ($4.998 billion), totaling $36.269 billion. This gives Google a Capex/EBITDA ratio of approximately 0.619.

Overall, both tech giants exhibit healthy Capex/EBITDA ratios, indicating they can fund AI initiatives with a portion of their annual profits. Alibaba is even pursuing AI while simultaneously engaging in a 'food delivery war.'

Such investments can be seen as profit-and-loss-based decisions. Companies allocate a fixed percentage of their profits to AI. However, OpenAI's deal with Oracle represents a debt-based AI investment, far more aggressive than Alibaba's or Google's approaches.

According to the order details, OpenAI has committed to purchasing $300 billion worth of computing power from Oracle over five years starting in 2027.

On the surface, this means OpenAI will spend $60 billion annually on cloud services. However, there's a prerequisite: Oracle must first expand its data centers to provide full services. To achieve this, Oracle plans to issue approximately $18 billion in new debt to fund the expansion. Since neither OpenAI nor Oracle has 'ready cash,' the deal will rely heavily on debt financing.

AI investment has shifted from profit-and-loss-based decisions to balance-sheet-driven 'high-stakes bets.' The AI race has officially entered a financing competition phase. Companies are now willing to pay higher risk premiums for AI.

From the perspective of the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC), we can broadly divide corporate investments into two stages, from low to high risk.

In the first stage, companies utilize low-cost funds, primarily cash and free cash flow. These funds are essentially 'internal' and readily available. As long as companies expect investment returns to exceed the interest earned from keeping cash idle, deploying these funds is justified.

This was the stage most tech giants were in previously. Shareholders allowed companies to use 'idle cash' for GPUs. When shareholders felt companies weren't investing enough in AI, they complained about insufficient focus, even triggering 'AI Capex too low' penalties that dragged down valuations.

In the second stage, companies begin financing AI through debt, equity, and flexible financing methods. These approaches provide rapid access to large sums but come with significantly higher costs. Companies must believe AI investments will yield higher returns.

This is where tech giants find themselves today. For example, AMD's partnership with OpenAI appears to be about selling GPUs. However, AMD effectively 'ceded' a 10% stake, which OpenAI then used to purchase GPUs. By locking in orders through equity, AMD essentially engaged in equity financing. Similarly, Elon Musk's xAI's collaboration with NVIDIA represents a flexible financing approach. Specifically, xAI borrows from a financing platform (SPV) and sells a portion of its equity to NVIDIA, using these funds to buy GPUs from NVIDIA.

The shift in investment strategies resembles players in Texas Hold'em choosing to go all-in with borrowed chips. If other players cannot match the stakes, they risk losing everything.

The AI investment 2.0 era has arrived.

02 OpenAI is Selling 'Tickets' to the AI Era

Behind these developments, questions arise.

Why are these tech giants willing to take such risks? Why increase AI investment stakes now?

On the surface, OpenAI's 'Midas touch' has inflated the valuations of every partner. While these orders cannot be immediately realized, expected revenues and profit margins can be directly translated into a company's Price-to-Earnings (PE) ratio. From a financing perspective, rising market values facilitate subsequent fundraising, further paving the way for AI infrastructure.

However, OpenAI's orders also reveal a certain ecological relationship.

For instance, among OpenAI, NVIDIA, and Oracle, OpenAI provides AI capabilities, NVIDIA supplies computing power, and Oracle offers data services, forming a relatively complete ecosystem. Similarly, OpenAI's partnerships with NVIDIA, AMD, and Broadcom involve NVIDIA providing mature GPUs, AMD supplementing GPU computing power, and Broadcom supplying custom AI chips and related networking infrastructure.

Summarizing these interconnected clues, a clear pattern emerges: OpenAI is positioning itself as a platform that coordinates resources from various parties, selling 'tickets' to board the 'AI Ark.'

On this ark, some focus on chips (e.g., NVIDIA and AMD), others on user products (e.g., third-party apps integrating ChatGPT and Sora), and still others on infrastructure (e.g., Oracle and Broadcom's data centers). All are striving toward the goal of Artificial Superintelligence (ASI).

The entrance to this ark, whether software or hardware, may be more unified than in the internet era.

For example, in edge AI, Qualcomm's first AI trend proposed this year is that 'AI is the new UI (User Interface).' AI will replace the traditional UI-centric interaction model of smart devices. Users will no longer need to click specific icons; instead, AI will provide intelligent interaction entry points tailored to them.

'ChatGPT aims to become the unified gateway, connecting users to various services,' as Sam mentioned in an interview. OpenAI has already become the world's largest AI application. Following this trend, Google's Gemini and Anthropic's Claude are vying to become the default user entry points.

According to Menlo's data, one in four U.S. users chooses ChatGPT as their primary gateway. The market is fiercely competitive, and while OpenAI leads, its advantage is not overwhelming. Regarding the importance of entry points, Menlo noted in its report, 'Consumers almost always try their default tools first.'

The capabilities and impact of AI that can continuously serve users may not be the top concern for the AI industry today.

Without sufficient AI infrastructure and hardware ecosystems, attempting to build stable businesses like food delivery, online shopping, or cloud services before the millennium would have been futile, given the lack of network infrastructure, billions of smart devices, and users.

'You need to generate electricity, build all physical infrastructure, handle everything outside data centers, manage chip manufacturing capacity, set up racks, and ensure consumer demand and business models can sustain it all. This requires many things to happen simultaneously,' as Sam stated. Joining the 'OpenAI Alliance' means collectively inflating the AI industry's scale with tech giants. Before AI can be widely monetized, the risk of a 'bubble burst' looms. Conversely, without consensus among players with defined roles, AI adoption faces immediate challenges.

Currently, AI's marginal costs may be significantly higher than in the internet era.

Generating each AI token incurs tangible computing and electricity costs. Today, when most AI entrepreneurs discuss business logic, phrases like 'clarify monetization from day one' and 'obvious marginal costs' dominate. Without perfect infrastructure (improved infrastructure), AI cannot fully demonstrate its technical capabilities. Even Sam admits, 'Insufficient computing power has delayed the release of new features and products.'

As a result, users struggle to experience AI's full potential.

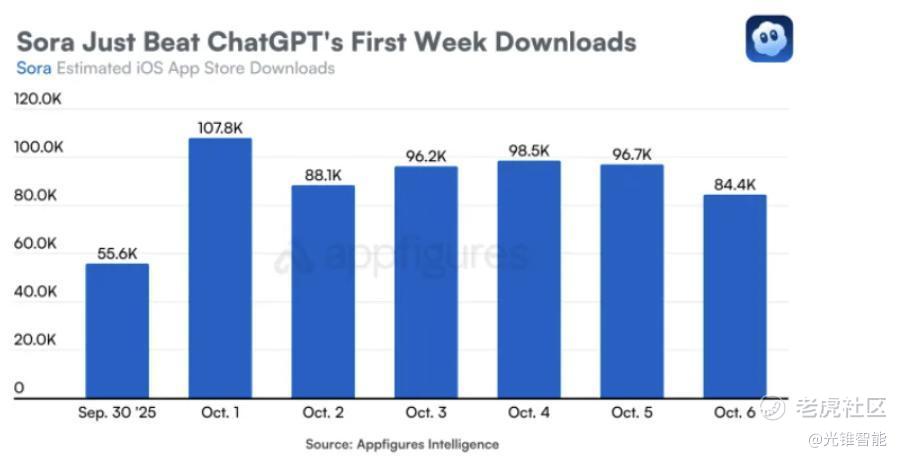

For example, Sora2, the viral video generation model from this year's National Day holiday, saw download numbers peak just three days after launch. With surging user numbers, 'strained' computing power struggled to deliver the same quality as official demo videos.

The same issue plagues domestic AI products. For instance, Doubao claims its model supports multi-round dialogues with tens of thousands of words in input and output. However, after naming Doubao, users find it forgets the name within a few dozen rounds of dialogue without creating new sessions. It may even mistakenly assume the user instructed it to use that name.

Perhaps the players accelerating AI infrastructure investments see AI's 'latent capabilities hampered by insufficient support.'

03 Conclusion

The AI era is racing toward a frenzied future. However, at this juncture, we may not need to overly fear a bubble.

In the era of large language models, we are witnessing AI transform industries while humanity reaches a new technical consensus.

'During the Bubble, optimistic analysts justified high PE ratios by claiming technology would dramatically boost productivity. They were wrong about specific companies but correct about the underlying principle,' as Paul Graham, the 'Godfather of Silicon Valley Startups,' summarized the internet era in 2004.

With AI adoption, AI is becoming a vital productivity tool. For example, AI office tools eliminate manual meeting note-taking; AI agents deliver daily industry briefings. 'Technology is a lever. It multiplies rather than adds. If current productivity ranges from 0 to 100, introducing a tenfold multiplier expands it to 0 to 1000,' Graham said.

On the eve of a new technological era, it is inherently challenging to estimate a market that is expected to far exceed $10 trillion. Perhaps, we can look to the history of the internet era as a reference point for envisioning the AI era.

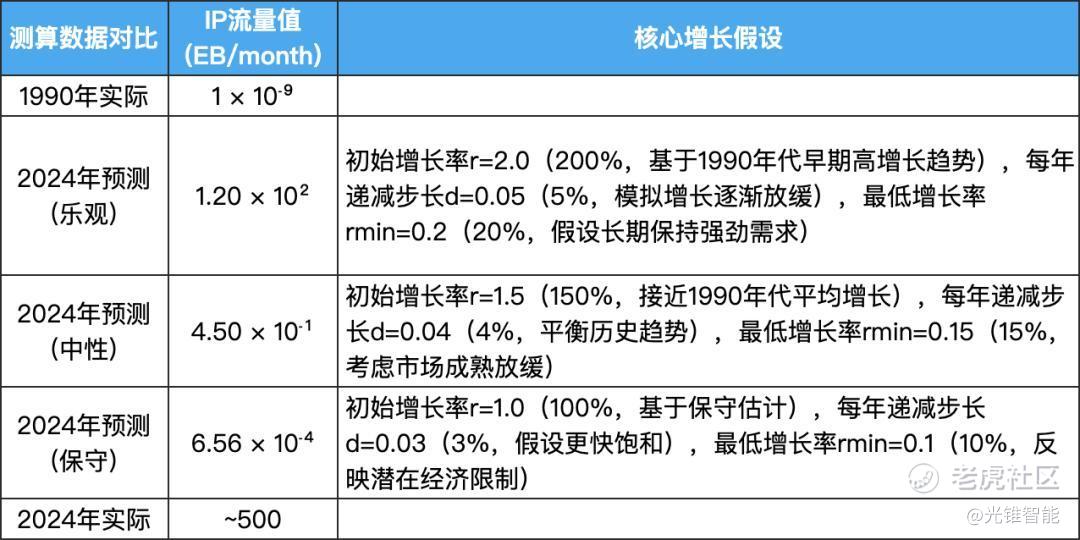

Since the fundamental unit of data transmission in the AI era is the Token, we can choose IP traffic from the internet era as a comparative reference. Suppose we find ourselves in 1990, on the cusp of the internet era, and estimate the current internet IP traffic from that perspective, then compare it to the actual figures. Grok's conclusion is that the actual internet IP traffic in 2024 is more than four times the 'optimistic estimate' from the past.

How could internet professionals in 1990 have possibly imagined the existence of cloud services, IoT, social media, and short videos today?

Today's coalition for AI development mirrors the players of the internet era. Perhaps, all we need is patience to witness how AI reshapes the world, and by working together, we can transcend limitations.