What has China's gaming industry gone through in the past 20 years of ChinaJoy?

![]() 08/12 2024

08/12 2024

![]() 574

574

Author | Xiaodong

Disclaimer | The cover image is sourced from the internet.

Original article by Jingzhe Research Institute. For reprinting, please leave a message to apply for permission.

On January 16, 2004, Beijing. The panic caused by SARS had gradually dissipated, and four days later would be the New Year's Eve. Amidst the festive atmosphere of welcoming the new year, the inaugural ChinaJoy, which was originally scheduled to open in the summer of 2003, was finally postponed and held at the Beijing Exhibition Hall.

As the first large-scale gaming exhibition held in China, the first ChinaJoy had many shortcomings: with an exhibition area of only 20,000 square meters spread across two halls, there were only around 100 participating exhibitors, and the number of visitors did not exceed 60,000. However, for China's gaming industry at that time, the holding of ChinaJoy was like a key unlocking the gaming market, ushering in a new era for the entire industry.

Today, 20 years later, when we view ChinaJoy as a special time dimension and look back at the fragments marked with the era and the characters who left their stories in the industry, we can reflect on the ups and downs and glories of China's gaming industry over the past two decades.

The Beginnings of a Competitive Industry

On the opening day of the first ChinaJoy, crowds queued outside the Beijing Exhibition Hall, braving the cold winter wind, while inside the hall was bustling with activity. The exhibitors' loudspeakers blared, and visitors carried large gift bags filled with promotional materials and souvenirs from various exhibitors – these two "staple programs" eventually became standard at subsequent ChinaJoys.

*People queuing up to attend the first ChinaJoy

At that time, the gaming market was transitioning from a single-player era to an online gaming era, and many so-called "industry giants" were merely "newcomers" with a few years of development. More accurately, China's gaming industry at that time was a "wild west" of competition, and those who first sensed the business opportunities became leaders – Shanda was one of them.

Flashback to six years earlier. 1998 was a special year for China's internet industry. In June, Liu Qiangdong founded JD.com in Beijing; in November, Pony Ma's Tencent was established in Shenzhen; and Jack Ma, who had failed in his entrepreneurial endeavors in Beijing, was preparing to return to Hangzhou with his team to start anew… Meanwhile, Chen Tianqiao, a recent graduate of the economics department at Fudan University, was just 25 years old.

As the secretary to the chairman of the Lujiazui Group, Chen Tianqiao enjoyed the benefits of a state-owned enterprise at a young age and was considered a "young talent" by many. However, he gave up his position at the state-owned enterprise and joined a securities company. A year later, China's stock market experienced the famous 519 rally, and within two months, the Shanghai Composite Index surged from below 1100 points to a peak of 1725 points, a gain of over 50%. Chen Tianqiao earned his first 500,000 yuan in the stock market.

In the stock market, Chen Tianqiao saw not only his "first pot of gold" but also business opportunities in the internet industry. In 1998, Chen Tianqiao and his wife, with their newly earned savings of 500,000 yuan, teamed up with his younger brother Chen Danian to rent a three-bedroom apartment in Pudong New Area, Shanghai, and established Shanda Interactive Entertainment. However, initially, Chen Tianqiao did not venture into gaming but aimed to create China's version of Disney. To this end, Shanda produced a large number of flash animations to establish an online animation website and acquired the copyright to "Black Cat Detective."

However, with the bursting of the internet bubble in the stock market in 2000, Chen Tianqiao had to shelve his dream of a "Chinese version of Disney" and look for other opportunities. At this point, the new business of game agency successfully caught his attention.

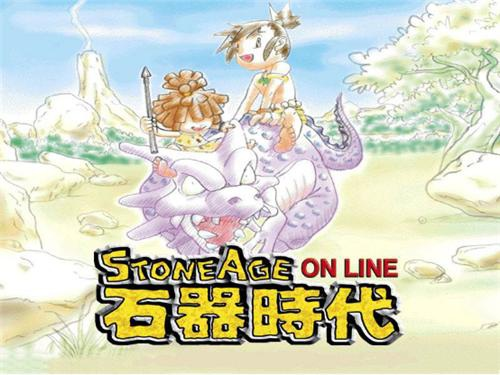

In 2001, "Stone Age," considered the progenitor of online games in China, swept the nation. At the same time, Korean game companies sought to expand their market by recruiting agents to develop overseas businesses. The Chinese market, with its geographical advantages, became the primary target for Korean game developers. Thus, in 2001, Shanda acquired the exclusive agency rights for the Korean online game "The Legend of Mir" from Actoz Soft in China for US$300,000, officially entering the gaming industry.

Chen Tianqiao's judgment about the internet industry was spot on. After the millennium, internet cafes rapidly spread from first-tier cities to towns and villages across the country, with online games and chat rooms becoming the primary online entertainment for a generation of young people. As a result, one month after the open beta of "The Legend of Mir," the number of concurrent online players quickly surpassed 400,000, and with its point card charging system and sales model in internet cafes, it contributed to Shanda's rapid cash flow growth.

Originally, Chen Tianqiao had anticipated it would take a year to recoup the investment, but "The Legend of Mir" became profitable within one month of its open beta. The point cards were in high demand, and it was said that some players, unable to wait for the point cards to be printed and sold, went directly to Shanda's offices to pay cash for the card numbers and passwords. In those days, without the need for equipment recycling or endorsements like "Join me, brothers!", most people in internet cafes, aside from those playing single-player games, were playing "The Legend of Mir."

Seeing the game's immense popularity, Chen Tianqiao immediately decided to use the profits from the first three months of the open beta to expand the servers, and as a result, the user base and revenue of "The Legend of Mir" grew exponentially like a snowball. According to industry media reports, Shanda achieved US$42 million in revenue and US$17 million in net profit in 2002 thanks to "The Legend of Mir." To sustain the game's popularity, Shanda later developed and launched "The Legend of Mir II" into the market, and these two "Legend of Mir" games created Shanda's own legend.

In March 2003, Shanda received a US$40 million investment from SoftBank Asia. One year and two months later, in May 2004, Shanda successfully listed on NASDAQ as the first domestic online gaming stock, raising US$152 million, creating the largest IPO for a Chinese internet company in the US at the time. Meanwhile, the number of concurrent online players of Shanda's games had grown to 1.2 million, far ahead of other gaming companies.

However, Shanda's success was not without flaws. After securing the top spot in China's gaming industry with "The Legend of Mir," the licensor Actoz suddenly publicly accused Shanda of defaulting on payments for revenue sharing from the game. Later, Shanda acquired a 28.96% stake in Actoz for US$91.7 million, becoming its largest shareholder. However, the copyright to "The Legend of Mir" was not solely held by Actoz. Wemade, which also held the copyright, granted the agency rights for "The Legend of Mir 3" to Guangtong Telecom, which had just ventured into the gaming sector, in 2003.

Thus, an intriguing scene unfolded at the first ChinaJoy: to promote their "orthodox" status, both Shanda and Guangtong spared no expense in promoting their respective "Legends," from the lineup of showgirls and cosplay stages to generous gift giveaways. This brutal yet straightforward competition within reasonable bounds was a true portrayal of the industry at the time.

Chaotic Prosperity

The successful holding of the first ChinaJoy demonstrated the vitality of China's gaming market to game developers, and more importantly, Shanda's success was traceable. Suddenly, local developers flocked to develop instant MMO (Massively Multiplayer Online) games similar to "The Legend of Mir," and even Shi Yuzhu, who had made a fortune in the health product market, invested in "Conquest." At the second ChinaJoy held in Shanghai in October 2004, "World of Warcraft," represented by The9 Limited (hereinafter referred to as "The9"), created a shared memory for all Chinese MMO players.

Before launching "World of Warcraft," The9 had already tasted the sweetness of the agency model.

In July 2002, The9 acquired the agency rights for "MU Online," an MMO game developed by Korean company Webzen, for US$2 million plus a 30% profit share in China. In February 2003, "MU Online" officially began charging fees in China. According to Zhu Jun, the founder of The9, who revealed in a media interview that "MU Online" generated an average daily revenue of 2 million yuan, with a profit margin exceeding 50%, resulting in a steady stream of cash flow. The pride in Zhu Jun's tone when discussing the profitability of "MU Online" did not hint at the fact that acquiring its agency rights was originally a risky gamble.

Similar to Chen Tianqiao's experience, Zhu Jun saw the development prospects of the internet industry and China's gaming industry in 1998 and registered a foreign-funded company named "Gamenow" in Hong Kong with US$500,000 in capital, simultaneously establishing the virtual community "GameNow.net," later renamed "The9 Limited."

After the bursting of the Chinese internet bubble in 2001, Zhu Jun struggled to pay his employees' salaries for a time. Later, in an interview with the media, Zhu Jun revealed that during The9's most difficult period, senior executives only held shares but did not receive salaries, and to maintain the company's normal operations, Zhu Jun himself had to contribute money every month. "At that time, I had to personally fund the company's operations, 1.2 million yuan per month, for 18 consecutive months," he said.

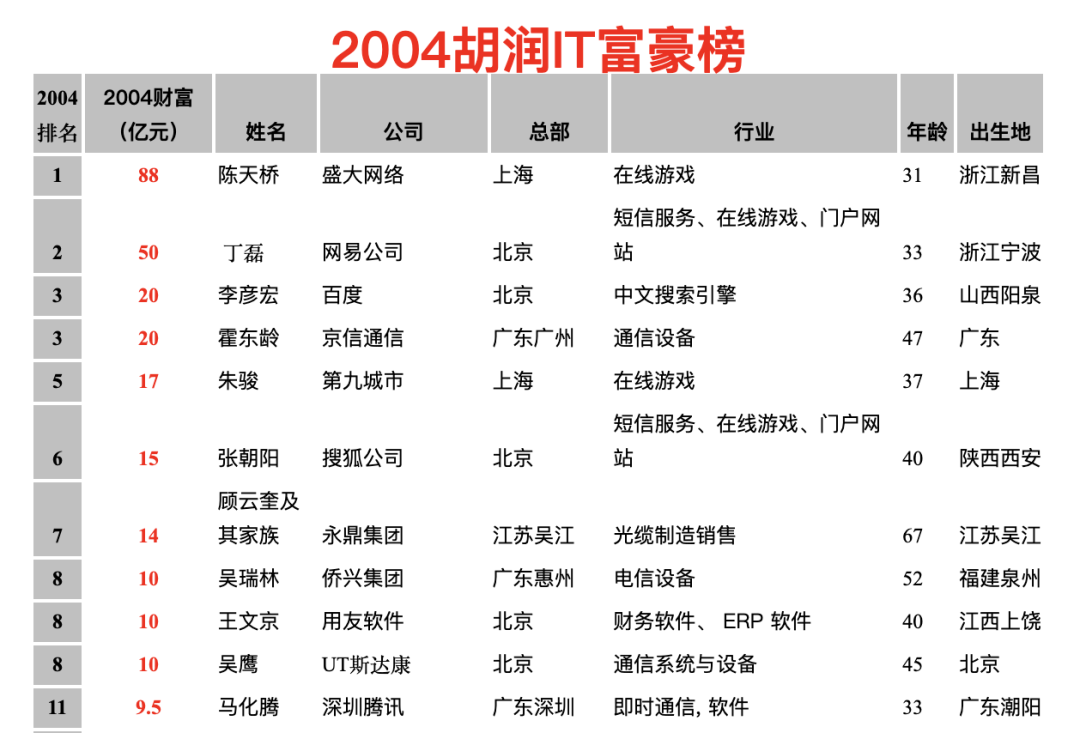

It was this experience of hitting rock bottom that allowed Zhu Jun to experience the thrill of "striking it rich overnight" with the success of "MU Online." In the 2004 Hurun IT Rich List, Chen Tianqiao topped the list with a net worth of 8.8 billion yuan, while Zhu Jun, the chairman of The9, ranked fifth with a fortune of 1.7 billion yuan.

There is no such thing as just one gamble; there are only countless gambles. In 2004, The9 poured all its resources into acquiring the four-year agency rights to "World of Warcraft" for the exorbitant price of "US$13 million + 22% profit share + US$70 million for independent datacenter construction fees." It is said that Blizzard initially intended to collaborate with Shanda but rejected their offer due to perceived harsh conditions, paving the way for Zhu Jun's gamble. With "World of Warcraft" in hand, The9 successfully listed on NASDAQ before the game was fully localized and officially launched, raising over US$100 million. Zhu Jun, whose personal wealth skyrocketed, later purchased the Shanghai Shenhua Football Club, entering the football industry earlier than real estate tycoons like Xu Jiayin.

The rise of Zhu Jun and The9 once again confirmed a fact: in the early stages of the gaming industry, daring to take risks could lead to a dramatic turnaround. As Shi Yuzhu of Giant Network Group described it, "This is an industry flowing with milk and honey. Right now, online games are the most profitable sector in the entire internet industry." From the perspective of game developers, securing game agency resources and attracting users through various marketing strategies was the path to success in the online gaming industry. Thus, ChinaJoy, as an essential platform linking games and players, became a stage for developers to showcase their strength and tactics.

At the second ChinaJoy, celebrities endorsing games became one of the most dazzling elements on-site. Miriam Yeung, as the spokesperson for NetEase's "Fantasy Westward Journey," attended the event and participated in the annual top ten game awards ceremony. Yao Zhuangxian, the producer of the domestic Chinese single-player RPG game "Chinese Paladin," and Hu Ge, who played "Li Xiaoyao" in the TV series adaptation, also appeared at exhibitor booths. Hu Yanbin, who had just debuted and won numerous awards, was invited to sing at the Softstar booth for the game "Mahjong 3-Missing One."

Apart from celebrities, exhibitors also invested heavily in their showgirl lineups, with the number and beauty of showgirls continuously increasing. This gave rise to famous showgirls such as Wei Jing Treasure Sun Ting, "Sina Princess" Ding Beili, Ayawawa, "Red Dress Girl" Xie Yufan, and "Bedridden Princess" Zhu Hong.

*Showgirl Ding Beili

The competition among exhibitors for the "most beautiful showgirl" at ChinaJoy reflected the chaotic prosperity of the gaming industry on the one hand and, on the other, revealed the hidden concern of game homogenization amid rapid industry development. The MMO model, represented by "The Legend of Mir," became the basic formula for virtually all large-scale games, with gameplay centered around monster killing, leveling up, joining guilds, and farming dungeons. When gameplay mechanics failed to bring new excitement, developers resorted to "off-field tactics.""To compete for players' attention, showgirls became increasingly attractive, with less and less clothing. In-game NPCs and poster characters also became increasingly exaggerated. As a result, Wu Shulin, then the Deputy Director of the General Administration of Press and Publication, publicly criticized some online games for their adverse effects on teenagers at the 6th ChinaJoy Summit Forum in 2008, implicitly accusing some companies of "adding program features unsuitable for minors in pursuit of economic benefits and player attention.""Behind the public criticism from regulatory authorities lay a prevalent issue in the gaming industry at the time: the vast majority of developers still relied on past experiences, focusing on a single product and maintaining player engagement through operational means, neglecting the development of game IPs. This resulted in short lifespans of three to five years for many games, with only premium games like "World of Warcraft" able to survive in the market for over a decade."Meanwhile, the scarcity of self-developed blockbusters and high-quality games limited the further development of game developers. As The9's agency rights to "World of Warcraft" expired in 2009, its business performance plummeted, underscoring the urgent need for China's gaming industry to shift to a faster-paced new trajectory.""A Turnaround in Pan-Entertainment""Why are there so few self-developed blockbusters? The core issue lies in the high risks involved.""Industry insiders have analyzed that over a decade ago, based on a 100-person development team and a two-year development cycle, the cost of developing a PC game was approximately 24 million yuan. Even if the team size was reduced to around 30 people and the development cycle compressed to 1.5 years, the development cost would still be at least 5.4 million yuan, not including marketing and promotion costs. For companies that had just entered the gaming industry after the millennium, taking the risk to develop games in-house undoubtedly posed a significant challenge."" ""Therefore, some developers chose to summarize the gameplay and essence of excellent games, making minor innovations in story backgrounds, character settings, etc., to shorten the development cycle and quickly bring products to market. However, this "copy-paste" model still failed to address the issue of game operation monotony. It was not until the context of pan-entertainment emerged that the gaming industry found the golden key to driving overall development beyond products alone – esports.

""Therefore, some developers chose to summarize the gameplay and essence of excellent games, making minor innovations in story backgrounds, character settings, etc., to shorten the development cycle and quickly bring products to market. However, this "copy-paste" model still failed to address the issue of game operation monotony. It was not until the context of pan-entertainment emerged that the gaming industry found the golden key to driving overall development beyond products alone – esports.

The elements of e-sports were already present at the first ChinaJoy. At that time, Lightone, which was competing with Shanda, held a FIFA competition among China, South Korea, and Germany on site and invited Duan Xuan, a well-known CCTV host, to host the event. Before ChinaJoy was held, on November 18, 2003, China's digital sports platform was officially launched, and the China Sports General Administration officially announced that e-sports had become the 99th official sport recognized by the Administration.

This means that games, once considered as frivolous distractions, have become competitive events. Players, in addition to playing games, have also started paying attention to various competitions, both domestically and internationally.

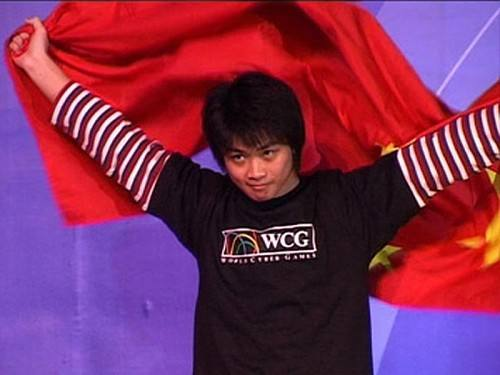

In 2005, Chinese e-sports player Li Xiaofeng (game ID: Sky) won the world championship in the real-time strategy game Warcraft III at the WCG World Finals held in Singapore, winning China's first individual gold medal in WCG. The following year, he successfully defended his title, becoming the first player to win back-to-back championships in this event. At the 9th ChinaJoy in 2011, Sky was also invited to perform an exhibition match.

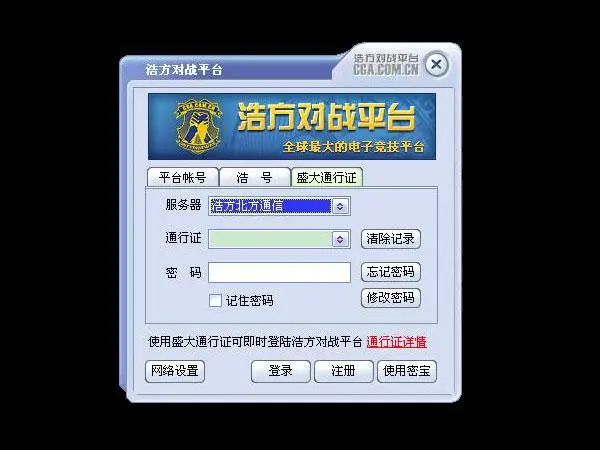

The celebrity effect of e-sports stars has rapidly driven the development of gaming competitions. Since Warcraft III is a single-player game, players need to register and log in to a third-party platform to compete. Therefore, platforms like Haofang Battle Platform in the early days, and later 11 Game Battle Platform, VS Game Battle Platform, and Tencent's TGA platform, began to emerge.

Founded in 2002, Haofang Battle Platform, although not the earliest battle platform in China, became the largest one domestically with the popularity of Warcraft III and DOTA maps. In 2006, Haofang had over 100 million registered users, surpassing the combined global sales of the three major single-player games - Counter-Strike, StarCraft, and Warcraft III.

As the saying goes, "People fear fame, pigs fear getting fat." Haofang's rise to prominence also attracted the attention of Aumei Electronics, the domestic agent of Warcraft III. Since many players and internet cafes were using pirated versions of Warcraft III at the time, Haofang, which provided battle services to these players, was sued by Aumei Electronics for infringement and was asked to pay 120 million yuan in compensation.

Interestingly, when many players discussed Haofang's lawsuit on forums at the time, they almost unanimously criticized Aumei Electronics, reflecting the unique early environment of the domestic gaming market.

Li Lijun, who has a technical background, initially focused on telecom system integration-related businesses for Haofang. When asked why he founded Haofang Platform, Li Lijun replied, "At that time, online games were already popular, but my team and I were still very passionate about supporting LAN games. When we had mature technology that allowed players to freely combine and play LAN games on the internet without geographical restrictions, we didn't hesitate to do it."

Although Aumei Electronics' lawsuit was later dismissed, the case made Haofang's founder Li Lijun consider selling the platform. Subsequently, Haofang was acquired by Shanda, which was interested in entering the e-sports battle platform, while Li Lijun and his key staff members founded the Qifan Platform and launched a game similar to the Warcraft III map "Dynasty Warriors," called "Three Kingdoms." This marked the beginning of a new model based on developing battle maps for existing games and opened up the market for MOBA-style competitive games.

As gaming competitions themselves attract a large number of players, in order to capture this audience, series competitions hosted by hardware and game manufacturers, such as NVIDIA's e-sports tournament and Tiandicheng's K1 TV Professional League, have become increasingly common. Additionally, as vertical content channels for players to watch competitions, gaming events broadcast platforms like Gamefy, GTV, and ImbaTV have extended the experience and value of games from within the computer screen to beyond it.

While the trend towards e-sports has not provided much assistance to game developers in the development process, as an extension of game value, e-sports has opened up a new stage for the operation of game products. Games like Tencent's CrossFire and League of Legends have surpassed the traditional life cycle of PC games through competition operations, raising the upper limit of game revenue.

According to a research report released by Gamma Data in January 2024, the proportion of CrossFire players watching related competitions is already at a high level, with even 26% of users temporarily stopping playing the game for various reasons but still maintaining a high level of interest in related competitions.

Furthermore, CrossFire enhances player engagement and drives paid content by adding tournament-related weapons, skins, sound effects, items, and sprays within the game. Nearly 60% of CrossFire users make tournament-related paid content their first choice, and CrossFire users are twice as likely to pay during major tournaments compared to other FPS game users. E-sports competitions have become an important driver of CrossFire's high revenue performance.

Another change brought about by the trend towards pan-entertainment in China's gaming industry is that the otaku community has gradually become the mainstream user base, which can also be seen from the changes in ChinaJoy.

Starting from the third ChinaJoy in 2005, the scale of the Cosplay Carnival has continued to expand, attracting high attention from otaku fans. In addition to the Showgirls arranged by manufacturers to portray characters from their own games on the Cos stage, more and more Cosplayers have joined in, making ChinaJoy a grand otaku event comparable to other large-scale comic conventions. As the gaming industry welcomes the infusion of fresh otaku blood, the rise of mobile internet has brought the entire industry onto a new track.

The True Prosperity of the Mobile Internet Era

Around 2012, smartphones gradually became ubiquitous, and a batch of "killer apps" like Fruit Ninja and Angry Birds dominated the App Store, introducing many players who were not traditionally part of the gaming community to mobile gaming. According to publicly available network data at the time, the number of mobile internet users in China exceeded 500 million in 2013, accounting for more than 80% of the overall internet user population, presenting a brand-new market to Chinese game manufacturers.

At the 13th ChinaJoy in 2015, Tencent brought a MOBA mobile game called Honor of Kings. An equal-scale "Crystal Base" and "Defense Tower" from the game were built on the exhibition stand, and popular streamers like Feng Timo were invited to live stream on site. Later, the game was renamed Arena of Valor and became one of Tencent Games' main sources of revenue.

In fact, after more than a decade of accumulation, China's gaming industry in the mobile era has developed a certain level of R&D strength and market grasp, gradually forming its own methodology. A notable phenomenon is that game company founders have gradually retreated to the background, replaced by independent game studios and game designers who communicate with players remotely. Without the "atmosphere of the Jianghu," the gaming industry may have fewer stories, but the entire ecosystem has become more scientific and efficient. This is precisely why China's gaming industry has truly flourished in the mobile era.

In 2016, NetEase showcased its self-developed game Onmyoji at ChinaJoy, which became a hit among the otaku community. A closer analysis of Onmyoji reveals that while the game adopts a semi-turn-based gameplay similar to that of Fantasy Westward Journey from over a decade ago, its otaku-focused art design, Japanese folklore worldview set in the Heian period of Japan, and unprecedentedly powerful voice actor lineup have successfully positioned Onmyoji as an otaku mobile game.

Behind this clever fusion of Oriental aesthetics and otaku culture lies the long-term accumulation of self-development capabilities and precise grasp of market demand by Chinese game manufacturers. At the same time, manufacturers have gradually realized that in the mobile gaming era, they must face a larger and more complex user base with diverse attributes. These users may include post-95s who have never been to an internet cafe or post-00s who have grown up with smartphones.

The demands of "new users" for gaming experiences have been increasing rapidly with the pace of the mobile gaming market's updates, forcing manufacturers to continuously innovate in gameplay, art design, and gaming experiences, ultimately shifting towards "boutique" development. To balance the investment costs of "boutique" development, manufacturers are no longer obsessed with creating "killer" hit products but rather turn hit products into mature IPs and achieve long-term operations through pan-entertainment formats such as porting PC games to mobile, e-sports competitions, and IP film adaptations.

However, every coin has two sides. While the "boutique" approach can indeed maximize resource utilization and form an IP matrix, the result of a game being "on standby" for too long may be that manufacturers lose their motivation and courage to innovate.

In January of this year, Pony Ma commented on Tencent's gaming business at the 2023 Tencent Holdings annual employee conference, describing it as "resting on its laurels." Pony's public mention of the gaming business was due to the lack of sufficient innovation and highlights in Tencent's gaming business in the face of challenges from new-generation gaming companies and rapid market changes.

Among the two mobile games that contribute significantly to Tencent Games' revenue, Arena of Valor was launched in 2015, and Game for Peace (formerly known as PlayerUnknown's Battlegrounds: Stimulus Battlegrounds) was launched in 2018. Although the life cycles of these two games have long exceeded those of most mobile games and still generate stable revenue, the fear of stagnation in growth has sounded the alarm for Tencent early on.

Financial report data shows that in the first quarter of 2023, Tencent Games' domestic market revenue was approximately 35.1 billion yuan, an increase of 6% year-on-year. By the second quarter, it declined to 31.8 billion yuan, a decrease of approximately 9.4% quarter-on-quarter. In the third quarter, Tencent Games' domestic market revenue increased by 5% year-on-year to 32.7 billion yuan, but the growth rate lagged behind the 14% in the international market. In the fourth quarter, Tencent's domestic market game revenue was 27 billion yuan, a year-on-year decrease of 3%. In the first quarter of 2024, Tencent Games' domestic market revenue was 34.5 billion yuan, a year-on-year decrease of 2%.

What is even more concerning for major companies is that their competitors have also changed.

Manufacturers Need to Break Down the "Dimensional Wall"

On social platforms, many netizens like to joke that whenever a country falls into chaos, a "hero will descend from the heavens." However, what the Chinese gaming industry has welcomed is the "descent of otaku."

In 2011, Liu Wei, Cai Haoyu, and Luo Yuhao, three avid otaku from Shanghai Jiao Tong University, used a 100,000 yuan interest-free loan obtained from participating in the Shanghai College Students' Innovation and Entrepreneurship Competition and a 50-square-meter office space that could be used free of charge for six months to establish miHoYo Studio with the mission of "saving the world with tech-savvy otaku."

In the early stages of its establishment, miHoYo suffered market setbacks but managed to avoid losses by timely adjusting from a buy-to-own payment model to an in-app purchase model. Later, miHoYo's operating data in its prospectus showed that its revenue in 2013 was 1.3074 million yuan, with a net profit of only 284,000 yuan - an amount that may not have been sufficient to expand the team at the time.

In 2014, miHoYo developed Honkai Impact 3rd with a team of seven people. Considering its tight financial situation and precise targeting of the otaku demographic, miHoYo chose to partner with Bilibili, which was just entering the game publishing arena. The two sides immediately agreed to collaborate and pushed Honkai Impact 3rd to the top of the domestic original anime mobile game rankings.

One year after its launch, Honkai Impact 3rd generated 65 million yuan in profit for miHoYo, while 60% of Bilibili's revenue in 2014 came from the joint operation of Honkai Impact 3rd. By the time Honkai Impact 3rd went into open beta in 2016, miHoYo's monthly revenue easily exceeded 100 million yuan. From starting from scratch to earning over 100 million yuan per month in just five years, miHoYo's achievements surpassed even those of PC game manufacturers who earned 2 million yuan per day in the PC era.

From an outsider's perspective, miHoYo's survival in the market as a small company without any major company backing is almost a miracle in the industry, but ultimately, it is because the times have changed.

In 2018, Analysys released the "Otaku Industry Research Report," which showed that users spent an average of over 1700 yuan annually on otaku-related products, with 5.68 million active otaku content consumers and 80.28 million fringe active otaku content consumers. In other words, otaku users, who are adept at "generating power for love," have literally created a blue ocean in the gaming arena with real money.

Sensing the industry opportunity, major companies have also flocked in. In 2017 and 2018, NetEase launched A Certain Magical Index and Million Arthur: Arcana Blood, while Tencent launched the big IP mobile game Fairy Tail. In early 2018, Paper Games launched the otome game Love and Producer, successfully tapping into the female player market, and later miHoYo also launched the similar legal romance and mystery mobile game Tears of Themis.

As the issue of "juvenile addiction" re-emerged, license approval became stricter after 2018. However, this did not prevent otaku games from creating new "legends."

In 2020, miHoYo participated in ChinaJoy for the first time. A month after the event ended, miHoYo's open-world adventure game Genshin Impact launched its global open beta. Six months after its mobile release, Genshin Impact generated over $1 billion in global revenue, becoming the first mobile game to reach this milestone.

By 2023, according to data released by data.ai, miHoYo and Tencent were the only two Chinese mobile game publishers with overseas revenue exceeding $1 billion that year. This was also the first time miHoYo surpassed Tencent to top the overseas revenue rankings. Nearly 20 years after Shanda debuted its PC game Legend at the first ChinaJoy, Chinese manufacturers' self-developed otaku mobile games have created new "legends" in their own way.

Not long ago, the 21st ChinaJoy was held as scheduled in Shanghai. Some players who attended the event lamented on social media that ChinaJoy was no longer "pure", because in addition to game manufacturers and Coser, there were also a large number of car manufacturers, mobile phone manufacturers, and consumer goods brands unrelated to games at the event. Even at ChinaJoy's heavyweight event, the China Digital Entertainment Expo & Conference (CDEC), games were no longer the only protagonist, and more audiences were attracted by the "Short Film Innovation Forum".

In fact, it is not difficult to understand that when games are an important part of ACG, other industries naturally want to reach their users through games. Looking back at the development of China's game industry in the past 20 years through ChinaJoy, in addition to lamenting the ups and downs of an industry, perhaps we can also find the way forward from the past glories and regrets of the industry.

It is worth affirming that since the first ChinaJoy, China's game industry has experienced fierce competition and industry regulation, and has become world-class. It has both imported and self-developed works, and has the ability to synchronize the release of domestic and overseas markets. In the future, what awaits Chinese game manufacturers is a market and stage larger than "ChinaJoy".