Don't let the 'traffic tax' exacerbate the 'stratification' of the e-commerce industry

![]() 11/07 2024

11/07 2024

![]() 566

566

The end goal of e-commerce competition should not be 'stratification'.

By She Zongming

Will e-commerce platforms become cyber department stores that collect 'traffic rent'?

Can the cost of acquiring traffic be reduced?

Do small and medium-sized businesses still have a chance to 'rise to prominence'?

These have become the 'three consecutive questions' that China's e-commerce industry must confront today.

This is not an unfounded concern: At present, many small and medium-sized businesses are trapped in the 'traffic tax'.

The broader context is that, from the perspective of the entire industry, the traffic dividend period has passed, and businesses have access to less and less free natural traffic that they can 'freeload', facing increasingly high customer acquisition costs.

Among them, small and medium-sized businesses are undoubtedly the most affected. In the bidding game where the top spot goes to the highest bidder, they easily become bystanders locked in by the '80-20 rule' and the 'power law'.

This is accompanied by a picture in the e-commerce sector where 'it is increasingly difficult for the underprivileged to succeed', reflecting an increasingly severe stratification of the e-commerce class structure.

In the science fiction work 'Folding Beijing', the world is folded into three strictly hierarchical spaces. Lao Dao, a garbage collector living in the third space, discovers a passage to other spaces. To save money for his daughter's kindergarten education, he illegally 'smuggles' himself into the first and second spaces to deliver messages, but ultimately has to return injured to the bottom third space.

Many small and medium-sized businesses are like Lao Dao in the e-commerce world, surviving in the 'folded' third space.

The 'traffic tax' is like a chasm, with brand businesses on one side and small and medium-sized businesses on the other.

How can we promote equal access to traffic and prevent many small and medium-sized businesses from 'not surviving more than three episodes' in the battle for traffic?

This is a question that e-commerce platforms must answer.

01

Facts have shown that the best period for applying Lei Jun's 'windfall theory' is the traffic dividend period.

For many years in the past, the prevailing narrative in the e-commerce sector was that 'all businesses are worth redoing'.

From Three Squirrels to Proya, internet e-commerce brands quickly established through substantial investments in traffic are common.

Zhang Liaoyuan, the founder of Three Squirrels, once said, 'An internet e-commerce brand can be built within five years', which has become a creed for many entrepreneurs.

After all, e-commerce platforms at that time were like affordable Northeastern restaurants, offering abundant paid traffic (main dishes) and generous free traffic (side dishes).

However, in recent years, many small and medium-sized businesses have reported that online business has become more challenging.

Even stores belonging to well-known internet celebrities have closed before this year's Double 11.

The direct reason is that the rising cost of acquiring traffic makes it difficult to sustain the growth model driven by substantial investments in traffic.

After announcing the cessation of broadcasts and store closure at the end of May this year, the founder of the women's wear brand Lola Code admitted in an interview that the high cost of traffic was the core reason for the closure, stating that 'the cost of traffic has increased tenfold. There were fewer people doing it before, but now there are more, and it's all about bidding for traffic, which is all cost.'

The 'traffic tax' has become a deterrent for many businesses that want to redo their operations online.

Traffic is not the problem; the problem is the lack of traffic, which has plunged many small and medium-sized businesses into a curse of short life. They often invest heavily in traffic, only to end up working for the platform.

▲Many small and medium-sized businesses are struggling with 'lack of traffic'.

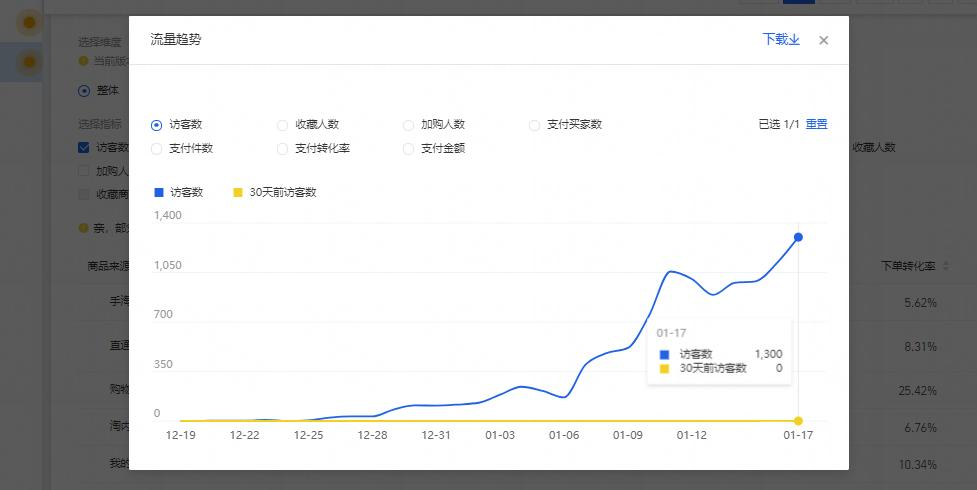

Media reports mention that Fang Yu, the head of an online toy water gun store, said that she used to spend 100 yuan a day on platform promotion, but now it costs four to five hundred yuan a day.

In May of this year, her store's promotion expenses reached 11,400 yuan, which nearly consumed 70% of her profits.

The high cost of traffic promotion has put many small and medium-sized businesses in a dilemma: Invest, and the meager profits may be eroded by marketing expenses; don't invest, and they don't have the 'natural water' like big brands.

As a result, marketing expenses have become a divider: Traffic resources tilt more towards big brands, gradually squeezing the survival space of small and medium-sized businesses.

This is why some people accuse e-commerce platforms of deviating from their original intentions: They once revolutionized the 'super rent' model with an online approach, becoming a haven for white-label startups; now, they have become rent-collecting 'establishment factions', resembling another type of commercial real estate company—traffic promotion fees are akin to the 'entrance fees' that have returned in a different guise.

02

Here comes the question: Is it reasonable to place all the blame on e-commerce platforms?

It is not reasonable. Several factors cannot be ignored—

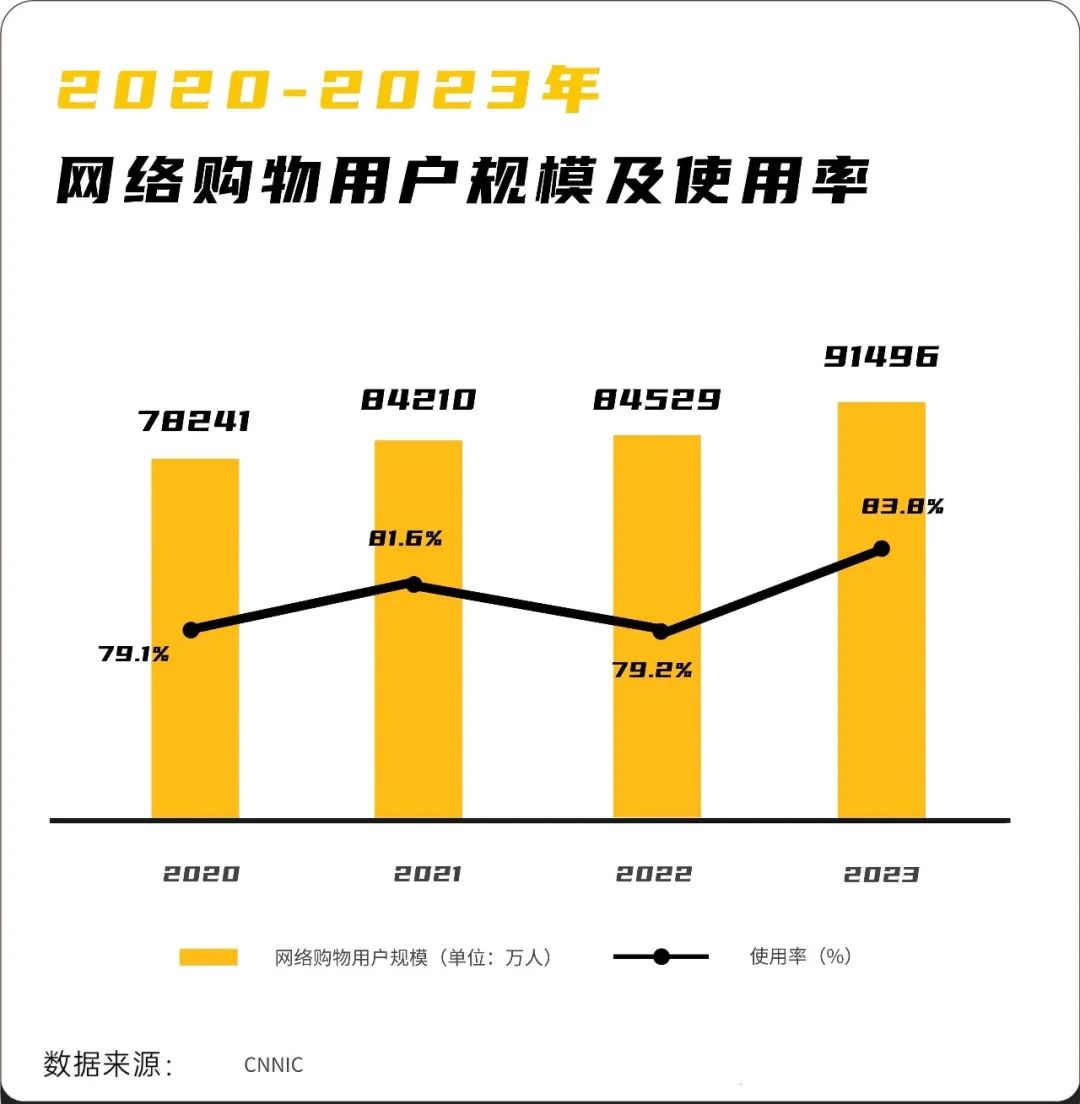

First, as e-commerce penetration reaches its peak, the marginal cost of acquiring platform traffic is also increasing.

The head of an online laundry bead brand said, 'In 2022, without investing in traffic, small and medium-sized live broadcast rooms could still receive natural traffic allocated by the platform', but in 2023, it became twice as difficult to obtain natural traffic.

It would be more accurate to say that the platform itself lacks traffic rather than being unwilling to give it away.

During the incremental development period, the platform's DAU grew exponentially, aiming for a thriving ecosystem, and distributing free traffic was not a problem.

However, during the stock development period, the growth momentum of the user base slowed down, the demand side lacked increment, the supply side had a large number of businesses and abundant product supply, and the problem of allocating high-quality traffic naturally arose.

▲With the user base reaching its peak, the traffic pools of many e-commerce platforms are insufficient.

Second, e-commerce platforms are not charities and also have profit-making aspirations.

After the 'loss-for-scale, profit-deferral' model reached its limits, it was inevitable for e-commerce platforms to focus on increasing monetization rates.

Traffic revenue is an important fulcrum for the monetization of e-commerce platforms.

It should also be noted that e-commerce platforms are also reducing the burden on small and medium-sized businesses.

Some platforms have introduced a package of relief measures such as service fee refunds, deposit reductions, exemption from logistics transit fees, and automatic refunds of technical service fees; some platforms have eliminated annual fees and introduced policies such as return treasure services, rapid refunds, and commission-free promotions during Double 11; still, other platforms support third-party sellers from three dimensions: traffic support, AI technology efficiency enhancement, and ultra-light asset operation.

China's three major platforms have launched 'billion-yuan relief' measures for merchants.

From focusing on 'billion-yuan subsidies' that provide low prices on the demand side to 'billion-yuan relief' that alleviates difficulties on the supply side, this is seen as an evolution of the e-commerce industry from 'consumption inclusiveness' to 'supply inclusiveness'.

The concessions made by e-commerce platforms undoubtedly reduce the burden on merchants. There is a formula in the e-commerce industry: Actual profit of merchants = Actual GMV - Actual cost. Here, GMV is closely related to traffic, conversion rate, average order value, and repurchase rate, while cost includes expenses such as store opening, operating tools, platform services, traffic promotion, logistics, and after-sales. Burden reduction requires comprehensive measures.

It should be noted that, for merchants, among the three major expenditures of basic service fees, commission points, and traffic promotion fees, the first two are minor, while the latter is the major one—it is common for merchants to invest more than 20-30% of their operating costs in marketing on a single platform.

Reducing the cost of traffic acquisition for merchants should be the key focus of reducing their burden.

03

Currently, many small and medium-sized businesses are adopting a 'two-legged' strategy: 1. Explore high-quality free traffic through SEO optimization; 2. Explore the optimal paid traffic model to maximize return on investment (ROI).

Many merchants use information optimization such as product title and keyword settings as a tool to uncover natural traffic.

At a time when e-commerce platforms are using AI and big data technologies to improve the accuracy of advertising placement, enhancing promotion effects through reasonable placement is also a common practice among many merchants.

From the perspective of merchants, improving placement effects is indeed a curvilinear way to reduce the burden, but it is more critical to jump out of the 'bidding mindset' and achieve a more systematic equal access to traffic—they want to improve placement effects and avoid being excluded from the traffic allocation system due to unaffordable 'traffic rent'.

This points to the proposition of equal access to traffic.

Equal access to traffic must be based on enlarging the pie—only with a continuous influx of fresh traffic can enough low-cost, high-quality products be nourished by traffic.

The essence of traffic lies in understanding human nature. In terms of e-commerce traffic, only when it meets user needs will users have the desire to open the app. In reality, users' needs for products are nothing more than 'more, faster, better, cheaper', and high cost-effectiveness is inherently pursued by users. High-cost-effectiveness products naturally have a 'traffic diversion' effect.

Therefore, e-commerce platforms can use high cost-effectiveness as the 'engine' for spontaneous traffic Import to expand and revitalize the traffic pool. When the source of traffic is abundant, the platform will naturally be lush with 'vegetation'.

▲Only by satisfying the deep needs of human nature will traffic flow in automatically.

Equal access to traffic must also be grounded in dividing the pie fairly—this cannot be achieved without resetting the underlying logic of traffic allocation.

Generally speaking, there are two rules for traffic allocation on e-commerce platforms: the highest bidder wins; the lowest bidder wins.

In the 'highest bidder wins' rule, the price refers to traffic promotion fees, corresponding to the centralized logic of 'people finding products' and the land rent mindset of collecting channel rents: Competitive bidding ranking is used as the basis for Showcase position recommendations, and promotion fees serve as the valve for traffic allocation. If merchants want to be prioritized or more prominently displayed on the shelves, they must purchase the platform's 'total traffic package' through competitive bidding.

However, this is often accompanied by merchants falling into a 'prisoner's dilemma' struggle to compete for recommended spots or slots, driving up traffic fees. Small and medium-sized businesses that cannot afford traffic promotion fees may not even receive a single click.

In the 'lowest bidder wins' rule, the price refers to product prices, corresponding to the decentralized logic of 'products finding people' and the people-centered approach of returning to the origin of supply and demand: The recommendation mechanism revolves around the most attractive price advantage, and how much exposure a product receives depends not on paid traffic but on cost-effectiveness.

Following this logic, even white-label or novice merchants can sell out products through free traffic attracted by high cost-effectiveness without paid promotions. This will guide merchants' focus from paid promotions to product cost-effectiveness, forcing the supply side to align with high cost-effectiveness.

These are two ways to 'cut the pie'. Clearly, the latter is more friendly to small and medium-sized businesses than the former.

04

To put it bluntly, only when e-commerce platforms can continuously acquire cheap traffic and get out of the traffic dilemma can they provide sufficient cheap traffic to merchants.

Only by switching the logic of traffic allocation from 'the highest bidder wins' to precise 'people-product' matching can small and medium-sized businesses obtain high-quality traffic without spending money.

After the traffic dividend disappears, e-commerce platforms need to find a new balance among the interests of users, merchants, and the platform itself, rather than 'fattening themselves while starving users and merchants'.

Relying on traffic rent for survival is ultimately unsustainable, and its side effect is to exacerbate the 'rich-poor gap' in the e-commerce industry with the 'traffic tax', leading to the atrophy of the e-commerce ecosystem.

To escape the trap of the 'traffic tax', the key lies in returning to the main line of supply and demand, establishing a virtuous cycle from better meeting demand to better improving supply, and achieving a mutually beneficial relationship among users, merchants, and the platform in a positive feedback loop of 'attracting more consumers with high cost-effectiveness—continuously reducing the cost of traffic acquisition for the platform—reducing operating costs for merchants—giving merchants more incentive to improve product cost-effectiveness'.

For e-commerce platforms, using the 'traffic tax' to leverage higher monetization rates is one 'algorithm', while promoting a more prosperous e-commerce ecosystem with equal access to traffic is another 'algorithm'. There is a difference in perspective between these two 'algorithms', reflecting short-sighted thinking versus long-term vision.

Behind traffic allocation lies value orientation. The value proposition of equal access to traffic lies in enhancing structural fairness through more reasonable rule design: 'Moonlight' should illuminate large, medium, and small businesses alike, rather than just shining on brand businesses, leaving small and medium-sized businesses lamenting alone, 'If only the moon would come…'

The development space for small and medium-sized businesses should not be blocked by the 'traffic tax', nor should the end goal of e-commerce competition be 'stratification'.