The Rise and Fall of the Final Fantasy Series: “Remember, All Glory is Fleeting”

![]() 02/06 2025

02/06 2025

![]() 646

646

Phantom Thief Leader's Note: Written in 2018, when I served as Chief Internet Analyst at a securities firm, this article is a profound research report imbued with emotion and logic. As a seasoned player of the Final Fantasy series, I've played and completed games from 1 to 10, including 10-2. This journey reflects not just the series' rise and fall but also mirrors the evolution of the gaming and broader content industries. Unfortunately, focusing solely on industry analysis rather than stock recommendations, it garnered little attention from the capital market despite its impact. However, this was never the intent. These in-depth reports aim to enhance fundamental research rather than elicit short-term market reactions. The article predates the remakes of Final Fantasy VII and the emergence of Final Fantasy XVI, but these developments haven't altered the series' decline, nor do they undermine the article's core arguments. Paradoxically, Final Fantasy XIV remains robust, consistently topping the list of most profitable MMOs globally.

Basic Conclusion

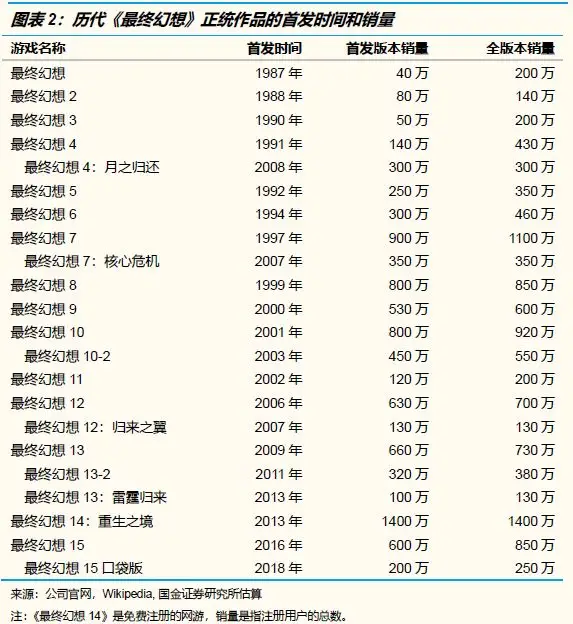

Once a cornerstone of the global gaming industry, the Final Fantasy series has enjoyed immense popularity since its inception in 1987. With 15 mainline games and over 30 spin-offs selling over 150 million copies across consoles, online, and mobile platforms, its rise was a product of Japanese game developers' golden age and the global expansion of Japanese culture.

Recently, however, high development costs, concentrated risks, and a shrinking Japanese market have contributed to the series' decline. Its cross-industry expansion into film and television has also faltered. The production company has resorted to "reheating old dishes" to maximize IP monetization, overdrawing its value and sparking backlash from players and media. This historical lesson serves as a cautionary tale for Chinese game developers.

Final Fantasy once defied IP economics, thriving on innovation and product iteration rather than IP reliance. Its eventual decline prompted a shift towards IP maintenance, highlighting that in the entertainment industry, IP's role is less significant than investors often assume. It's just one piece of the success puzzle.

Since 2007, the series has attempted to revitalize itself through the mobile game market with limited success. Mobile gaming has its limitations, and players' willingness to pay for classic IPs is waning. Excessive mobile game development has tarnished the Final Fantasy IP, sounding an alarm for other classic IPs.

After nearly a decade of mobile game dominance and global integration, the gaming industry stands at a crossroads. The mobile market is nearing saturation, lacking new blockbuster themes, and high development costs hinder innovation. In gaming, there's no such thing as "easy money"; change is the only constant. Without innovative directions, the market risks stagnation.

Integration of mobile and console gaming platforms may offer a way forward, with Nintendo Switch leading the charge. Combining mobile portability with console expertise could unleash new market demand. In the 5G era, high-speed mobile internet could make "cloud gaming" a reality.

To combat homogenization and encourage innovation, Tencent Holdings, Perfect World, and NetEase are investing in independent games. WeGame and Steam China could become hubs for game innovation, contingent on supportive regulatory policies.

As players mature, their tastes diversify, making segmented and niche markets increasingly important. Platforms like Bilibili for secondary game distribution and Kingsoft Software for independent IP development will continue to benefit from this trend.

Final Fantasy in its Heyday: Top Content Determines Channels' Fate

In China, debate rages among investors and professionals: Is it the channel/platform or the content/product that reigns supreme in the cultural and entertainment industry? So far, the "channel is king" proposition prevails, as channels often suppress content rather than the other way around. However, "content determining channels' fate" has occurred, most notably twice with the Final Fantasy series.

On January 29, 2000, Square, the series' developer and publisher, held a grand "Square Millennium" event in Yokohama, Japan, announcing Final Fantasy IX, X, and XI. IX would be on Sony's PS (Playstation), nearing the end of its life cycle, while X and XI would be on the upcoming PS2. This event virtually shaped the global gaming industry for the next decade: Sega exited console hardware manufacturing, transforming into a software vendor; Microsoft launched the Xbox; leaving Sony, Nintendo, and Microsoft as the major platforms.

Without Final Fantasy, Sega DC (Dreamcast) might have triumphed: launched earlier than PS2, with powerful features and diverse software. During the 1999 Christmas season, DCs sold out across the US, plagued only by production shortages. However, with new Final Fantasy announcements, Sega was cornered—the series ran only on Sony's PS/PS2. Players, impressed by the full 3D demo of Final Fantasy X and multiplayer battles of XI, voted with their feet. Sega DC's sales never met expectations, and PS2 became the most successful console ever.

This was the second time Final Fantasy dictated a console's success. In 1995, Square faced a tough choice: release Final Fantasy VII on Nintendo's N64 or Sony's PS? Nintendo had dominated consoles for a decade, with an unassailable industrial chain advantage, while Sony was a newcomer from the home appliance industry. Square chose PS for its larger storage (via optical discs) enabling "cinematic" gaming. This decision shook Nintendo's foundation—mainstream players in Japan and the US couldn't accept a console without Final Fantasy. When VII released in 1997, it became PS's crown jewel, breaking global console game sales records. Since then, a consensus emerged: whoever wins Square wins the world, or more accurately, whoever wins Final Fantasy wins the world.

From 1987 to 2006, Final Fantasy released 15 generations and 22 mainline games, selling nearly 100 million copies. Including spin-offs, sales surpassed 150 million. During its heyday, it not only determined platforms' fate but also dictated industry trends: VI ushered in the RPG era; VII pioneered 3D cinematic storytelling; X achieved full 3D scenes and voice acting; XI was one of the earliest globally operated MMORPGs; XII evolved from turn-based to action RPG... Final Fantasy didn't follow trends; it set them.

In 2008, when asked about Final Fantasy XIII's platforms, Square executives responded arrogantly: "We don't want PS3 to lose too badly, so we'll release it on PS3; but we also don't want PS3 to win too easily, so we'll release it on other platforms too." XIII launched simultaneously on Sony's PS3, Microsoft's Xbox 360, and PC. Despite declining, Final Fantasy still dictated major platforms' fate. Where did this confidence come from? How was this top-tier IP, spanning over 30 years and 100 countries, forged?

From Rise to Peak: The Road to Success of the Final Fantasy Series

Final Fantasy's rise from the late 1980s to its 2000s peak was a mix of necessity and chance. The rapidly developing Japanese game industry was bound to produce world-class developers and IPs. Square, an unknown small developer, gathered talented producers, moving from imitation to innovation. Early success propelled Square to relentlessly accumulate technical and creative advantages, pushing Final Fantasy to unprecedented heights.

Early Final Fantasy: Innovation meant being the first to imitate, constantly trial and error, striving for excellence.

In 1983, Nintendo released the groundbreaking FC (Famicom) console, known as the "Red and White Machine," marking the birth of the modern gaming industry. Within a few years, consoles entered tens of millions of households worldwide, making electronic games a mainstream home entertainment form. Before this, gaming was limited to arcades or expensive early computers.

Nintendo dominated the industry for two generations: FC in the 1980s and SFC (Super Famicom) in the 1990s. For over a decade, players worldwide enjoyed inserting cartridges into Nintendo consoles, picking up controllers for leisurely entertainment. However, games were often too simple, lacking playtime and challenges. Completion times were usually within 10 minutes, even for groundbreaking games like Super Mario.

Most 1980s games fell into action or shooting categories. Platform action (Super Mario), flight shooting (Salamander), action fighting (Wrestling)... While novel, they soon felt repetitive. Could electronic games be deeper and broader, occupying more user time? Everyone wanted to know.

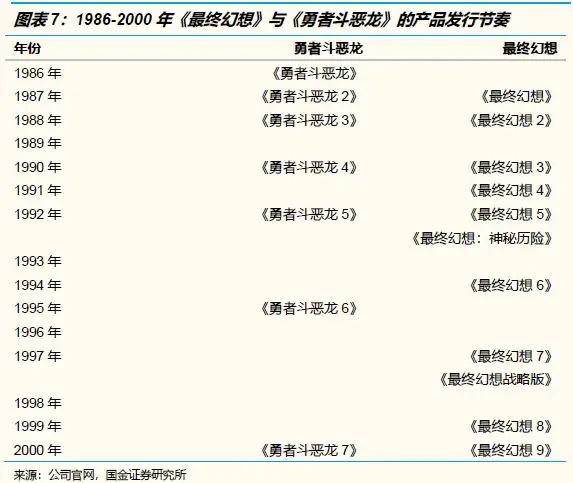

In 1986, Japanese developer Enix answered with the world's first large-scale commercial RPG—Dragon Quest. Early RPGs like Wizardry and Ultima existed on PCs, but their gameplay was cumbersome, lacking a mass audience. Through modifications and innovations, Dragon Quest made RPGs mainstream: simple yet complete storylines, turn-based combat, large map exploration, multi-character team-ups, and a rich "sword and magic" fantasy style. Players discovered games worth tens of hours, with vast worlds to explore and linear storylines to experience. Dragon Quest was a milestone.

Meanwhile, fledgling Square struggled for survival. By 1986, Square had released six failed games across PC and FC platforms, spanning adventure, action, and shooting genres. R&D head Sakaguchi Hironobu repeatedly proposed an RPG but was rejected. Dragon Quest's success changed management's mind, allowing him to develop a similar RPG.

Drawing from Dragon Quest, Sakaguchi Hironobu innovated: players could choose professions like warriors, thieves, and magicians (Dragon Quest had no profession settings), creating unique adventure teams; battles were in third-person perspective (Dragon Quest was first-person), accommodating more information; and the storyline was deeper and more complex. Unsure of success, he named it Final Fantasy—if it failed, it would be Square's last game before bankruptcy.

Fortunately, this risky venture culminated in triumph—Final Fantasy sold 400,000 copies upon its initial release, a mere one-fifth of Dragon Quest's sales, yet sufficient for Square's survival and growth. From then on, Sakaguchi Hironobu enjoyed complete autonomy in forming a team and developing products. Consequently, the Final Fantasy series maintained a pace of releasing a new game every 1-2 years. By the time Final Fantasy V was released in 1992, the series had been recognized as one of Japan's two major "national RPGs," alongside Dragon Quest, and had also garnered success in the North American and European markets. Square's rise to become a leading global game company was almost entirely attributable to the Final Fantasy series.

The birth of Final Fantasy is undoubtedly the fruit of imitating Dragon Quest and earlier RPGs like Wizardry and Ultima. After all, innovation often sprouts from imitation, a highly cost-effective strategy. The crux lies in Square's bold reforms and trial-and-error approach after establishing a foothold through imitation: Final Fantasy II surprisingly abolished the leveling system; the third generation reinstated it and introduced a more intricate job system; the fourth generation transitioned from the traditional turn-based system to a semi-real-time system; the fifth generation introduced an "ability point" system independent of experience points... For players, each iteration of Final Fantasy brought numerous novel ideas with a high degree of polish and virtually no major flaws. Furthermore, with the continuous advancement of development technology, the depth and expressive power of the games were also continually enhanced.

For the RPG genre as a whole, the 1980s to 1990s can be deemed a golden period: Game console hardware at that time was not yet sufficiently developed to handle complex data and offered limited visual effects. Genres such as FPS, SLG, RTS, ARPG, and sandbox, which are now popular, struggled to shine on the hardware of that era. In contrast, turn-based RPGs, represented by Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest, thrived: They did not require extensive real-time data processing, had less demanding graphics requirements, and had an overall storage capacity within an acceptable range. Final Fantasy stood at the right wind vane, possessing a certain first-mover advantage and swiftly expanding this advantage. Thus, success became a highly probable outcome.

Towards the peak: First-class content + forward-looking marketing = a global classic IP

From the late 1980s to early 1990s, Final Fantasy was consistently overshadowed by Dragon Quest: The latter was the spiritual cornerstone of the Japanese people, and its release date invariably sparked tens of thousands of truancy and absenteeism incidents, even drawing the attention of the Japanese government. Although Final Fantasy was not inferior in quality, its popularity and market heat were far less. The first generation of Dragon Quest sold over 2 million copies in Japan, while Final Fantasy did not achieve this milestone until the fifth generation.

However, in the mid-1990s, a subtle shift occurred: The release frequency of new Dragon Quest games drastically declined, with gaps of 3-5 years, and the quality of the works became severely inconsistent; Final Fantasy, on the other hand, maintained a higher release frequency, with word-of-mouth and sales showing a trend of catching up, and several derivative works were also launched. Entering the 21st century, Dragon Quest lagged significantly behind Final Fantasy in the global market and struggled to maintain its edge even in Japan. Why was that?

The answer lies in content control. The development and distribution of Final Fantasy were handled exclusively by Square, with a highly stable development team deeply passionate about this IP; Enix, the publisher of Dragon Quest, was not responsible for development, with most of the development work outsourced to third parties. Although the main creative team of Dragon Quest remained largely stable, it was challenging to guarantee progress and final completion. By the late 1990s, the problem became increasingly acute: The development team of Final Fantasy VII remained above 100 people, while Dragon Quest VII only had 35; the Final Fantasy series could develop 2-3 works simultaneously, while new products in the Dragon Quest series were continuously delayed. Additionally, the outsourcing development model made it difficult for Enix to keep pace with technological advancements – when Dragon Quest VII was released in 2000, its graphics quality was already over 3 years behind mainstream games.

The success of the Final Fantasy series is primarily the success of its core creative team. In the first five generations, producer and main planner Sakaguchi Hironobu, designer Amano Yoshitaka, and composer Uematsu Nobuo formed an "iron triangle" with a profound understanding and strong passion for the Final Fantasy IP. Starting from the sixth generation, Sakaguchi gradually stepped back from the front line, but the producers he trained, Hashimoto Motomu, and planners Kitase Kazushige and Itō Hiroyuki, seamlessly took over the heavy responsibility. Simultaneously, Square nurtured fresh talent such as designers Takahashi Tetsuya and Nomura Tetsuya, screenwriters Noda Kazunori and Kato Masato, and musician Mizutani Naoshi. In the early 2000s, most members of the Final Fantasy development team had experience developing multiple works, which was highly beneficial to the continuity of the IP.

Years later, when Nintendo President Iwata Satoru inquired why the early Final Fantasy games could achieve such high quality and rapid development speed, Sakaguchi replied: At that time, the game industry was undergoing rapid technological advancements in software and hardware, and player demand was also evolving swiftly; Square was permeated with an innovative sense of leading the trend, with every employee believing that their work would impact the entire world, and even regarded innovation as their obligation, so they never felt fatigued. This vibrant spirit is rare in the gaming industry of any country.

It must be acknowledged that Square's advantage in content development was built on a significant premise: In the 1990s, European and American game companies were generally weaker than Japanese companies and struggled to gain mainstream market status. Today's renowned European and American gaming giants such as EA, Ubisoft, and Activision Blizzard all began with PC games in their early years, and the PC was not the most mainstream gaming platform at that time. In genres where Japanese companies excelled, such as action shooting, fighting, and RPGs, the presence of European and American companies was weak. The highly developed Japanese economy in the 1990s also provided Japanese companies with inexhaustible market resources and capital advantages. In other words, had Square not been a Japanese company, it would have been impossible for it to develop such a powerful IP as Final Fantasy. The decline of the Japanese economy and the progress of European and American technological strength also foreshadowed the decline of the Final Fantasy series after the 2000s.

Although North America lacked world-class game companies in the 1990s, it was not devoid of players: Nintendo's Super Mario series and Sega's Sonic series achieved great success in the United States. North American players were not unfamiliar with RPGs, as early RPGs like Wizardry and Ultima originated in the United States, and RPG masterpieces such as Might and Magic and Baldur's Gate emerged in the United States in the late 1990s. Therefore, the Final Fantasy series began cultivating the North American market from 1990. During the localization process, the production team would not only translate the game text into English but also make significant modifications to scenes, characters, and even gameplay based on the usage habits and culture of North American users. By the time Final Fantasy VI was released in 1994, Square had launched a large-scale marketing offensive in North America; Europe also became a key region for marketing for the first time.

Until the sixth generation, the Final Fantasy series had achieved only limited commercial success in Europe and the United States; its total sales in these regions were weaker than those of the Dragon Quest series, not to mention classics like Super Mario, The Legend of Zelda, and Sonic. However, the IP image of Final Fantasy had been firmly established, and "turn-based RPG = Dragon Quest & Final Fantasy" was recognized by European and American players. Starting from the sixth generation, the plot and art style of the Final Fantasy series gradually leaned towards science fiction, making it easier for European and American players to accept. All it took was a groundbreaking work, and the European and American markets would fall like dominoes – that work was Final Fantasy VII.

Golden Age: In the early 21st century, Final Fantasy was synonymous with the best games

In the mid-1990s, the gaming industry witnessed unprecedented technological changes: Advances in computer graphics processing capabilities made 3D graphics a reality; the popularization of optical disc media significantly increased game storage space; and the development of multimedia technology enabled game consoles and PCs to display complex animations and sound effects. The prevalent view in the gaming industry at that time was that future games would be "cinematic," with the ultimate development of games being "interactive movies." It should be noted that the gaming industry is still moving towards this goal today.

From the day it commenced developing Final Fantasy VII in 1994, Square decided that it would be a "true 3D game." Specifically, the game characters would use 3D modeling, while the background environment would utilize 2D textures converted from 3D modeling; although it was still a step short of full 3D modeling, this was the optimal solution achievable with the technological conditions at that time. To achieve "cinematic storytelling," a plethora of 3D animations would be incorporated into the game, and the length of the plot would also set a new historical high. To this end, Square spared no expense, investing $40 million in research and development and establishing a 150-person development team. Such a scale of investment was shocking at the time and is still substantial enough to develop a high-level game today.

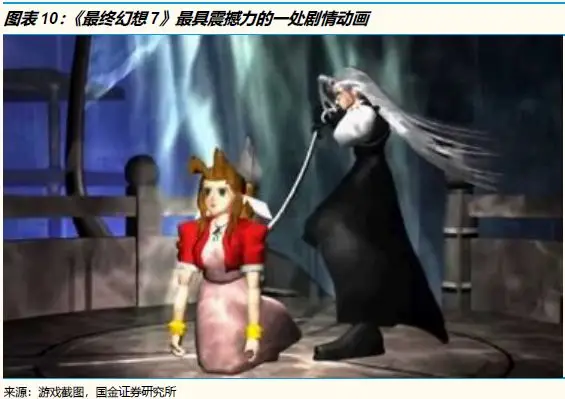

In terms of plot, Square abandoned the previous "swords and magic" style and ventured into science fiction. In Final Fantasy VII, players can witness settings with a "space opera" style, such as spaceships, laser swords, and genetic modifications. The characters and story are significantly more complex and solemn than previous works, filled with tragedy and fatalism, more suitable for older players and consuming longer gameplay time. To be fair, the plot of Final Fantasy VII rivals top-tier science fiction movies.

The challenge was that the mainstream Nintendo SFC platform and the N64 platform being developed by Nintendo at that time lacked sufficient graphical processing power and storage space to support the ambitions of Final Fantasy VII. After meticulous consideration, Square announced in February 1996 that Final Fantasy VII would switch to Sony's PS platform, which boasted stronger 3D technology and optical disc media. This decision was risky; who could have predicted that Sony would triumph over the thriving Nintendo? However, when the product was released in 1997, all doubts were dispelled. The majestic cities, deep and dark streets, and characters with rich expressions... it was an interactive movie. In comparison, all previous games seemed too simplistic.

The total sales of the first version of Final Fantasy VII exceeded 9 million copies. It was the best-selling new game in Japan, North America, and Europe. It accomplished a triple mission: First, it established 3D modeling and "cinematic storytelling" as the undisputed mainstream in the gaming industry; second, it solidified Sony's PS as the undisputed winner of the game platform competition in the late 1990s; finally, it made RPGs (especially turn-based RPGs) the undisputed market mainstream for the next decade.

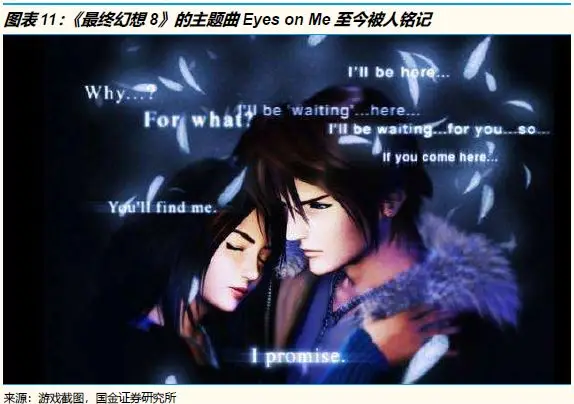

Following the resounding success of Final Fantasy VII, Square reached its historical peak in terms of technology, capital, brand, and morale, becoming almost omnipotent. In 1999, Final Fantasy VIII was released, and its opening and ending animations are still considered the pinnacle of gaming history. The 3D modeling technology that was not yet mature in the previous generation of works had been significantly optimized in this iteration, with more realistic and vivid character designs. More importantly, Square clearly developed this game with pop culture as the compass: The main plot revolved entirely around a love story, which was unprecedented; a theme song sung by a real person was added for the first time, namely the renowned "Eyes on Me"; and "Hollywood elements" such as science fiction, magic, suspense, and even time travel were emphasized like never before. Final Fantasy VIII was not an isolated game but bore the profound imprint of global pop culture in the late 1990s.

Square's nurturing of the European and American markets bore fruit at the right time: over half of the 8 million sales of Final Fantasy VIII came from these regions, and it also garnered the "Game of the Year Award" from North American players. Encouraged by this success, Square began seriously contemplating collaboration with American entertainment giants like Disney, leading to the later popular Crisis Core: Final Fantasy VII series. Released in 2000, Final Fantasy IX visibly leaned towards the artistic style of American cartoons and reintroduced the medieval "swords and magic" plot setting. This marked a significant effort by the Final Fantasy series to explore style diversification and globalization, but unfortunately, the reception was underwhelming as players had grown accustomed to the realistic style and science fiction setting. Sales of the initial version of Final Fantasy IX barely surpassed 5 million, a far cry from the previous two installments. Embarrassingly, Sakaguchi was deeply involved in this project, even personally penning the script. This was a grim omen: the older generation of Final Fantasy creators might be losing touch with market demand, and Square could not stay at the forefront of trends indefinitely.

Nevertheless, the release of Final Fantasy X in 2001 was enough to bring a smile back to Square's face. Leveraging the powerful computing power of Sony's PS2 platform, the game featured characters and scenes entirely modeled in 3D, a significant leap in picture quality. The introduction of real human voices and a record-high duration of 3D animations further enhanced the experience. The game extensively used motion capture and facial expression capture technology, which was still nascent even in the film industry. If the seventh generation was "cinematic," then the tenth generation was "dreamlike," leaving an almost irreplaceable impact on players. The game's plot, a classic "love tragedy," was not only imaginative but also brutally harsh. At the dawn of the 21st century, countless players adorned their walls with posters of the heroine Yuna, and many sighed at the tragic ending while listening to the theme song. Sales of the initial version of Final Fantasy X exceeded 8 million again, with two-thirds coming from outside Japan. At this juncture, Final Fantasy seemed omnipotent!

However, reality struck hard: while Final Fantasy X dominated various game charts, developer Square Enix was on the brink of bankruptcy. In February 2001, producer Hironobu Sakaguchi resigned; in October, Square Enix sought Sony's investment to sustain operations; in November, founder and CEO Hisashi Suzuki also stepped down. After a series of complex restructurings, Square Enix merged with its long-time rival Enix in 2003. Finally, the publishers of Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest united, but both companies were teetering on the edge of collapse; the golden age of Final Fantasy was also drawing to a close. How did this happen? Even today, recalling these events, people still find it hard to believe. Stagnation and Decline: How Final Fantasy Gradually Became a Second-Tier IP

On the surface, the decline of the Final Fantasy series stemmed from a failed attempt at 'IP crossover.' Essentially, soaring game development costs, Japan's economic downturn, and the gaming industry's shift of focus to North America were the true culprits behind Final Fantasy's downfall. Unfortunately, Square Enix failed to adequately address these challenges and timely embrace the Internet era. By the 2010s, Final Fantasy had stepped down from its pedestal as a top IP, a painful lesson etched in history.

Excessive Costs, Aggressive Strategies, and Risky Ventures

While developing Final Fantasy IX, gold producer Hironobu Sakaguchi diverted much of his attention to movies. He wanted to personally direct a sci-fi CG animated film representing the pinnacle of technology at that time—Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within. Square Enix established a film company for this purpose. Over the four-year production cycle, approximately 200 developers and over 1,000 workstations were utilized, costing $107 million; another $30 million was spent on promotion and distribution.

To be fair, Square Enix's venture was justified: in the late 1990s, CG films like Disney's Toy Story series and DreamWorks' Antz achieved commercial success, and CG was clearly the future of animation. The popularity of the Final Fantasy IP was at its peak, the development team had accumulated rich experience in animation production, and Columbia Pictures, one of the Hollywood Big Six, was willing to handle global distribution. However, the result was a nightmare: the global box office of Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within was only $85 million, resulting in a total loss of $94 million for the production and distribution sides.

Media consensus was that Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within was the most technologically advanced CG film at that time, but the plot was weak, and the theme lacked appeal. After all, this was Square Enix's maiden foray into film production, with a focus entirely on technology, leading to severe cost overruns. The industrial system and business logic of movies are fundamentally different from those of games, but Square Enix no longer had the opportunity to learn—after incurring huge losses, it completely withdrew from the film business in 2002. This was indeed a tragic ending: the lessons learned from the colossal investment of $137 million were not passed down.

In the following decade, Final Fantasy only released one animated series, one OVA, and one DVD animated film, all focused on cost control and limited distribution. In 2016, to coincide with the release of Final Fantasy XV, Square Enix authorized a third party to produce the animated film Final Fantasy: Kingsglaive. The film's commercial performance was also poor, with a global box office of only $9 million. The reason is straightforward: with declining technical prowess and insufficient funding, Square Enix and its partners could no longer produce world-class films; the popularity of the Final Fantasy IP had long passed its zenith.

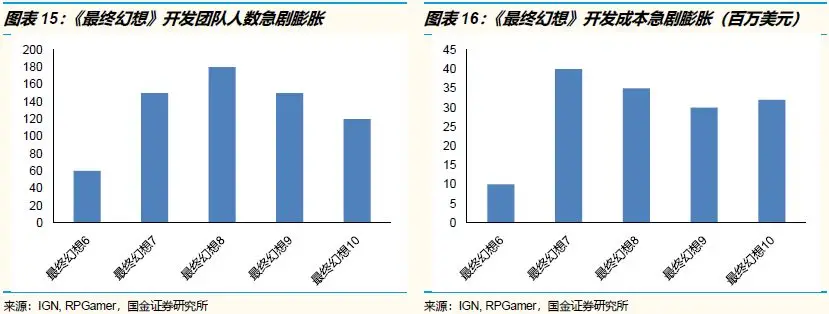

Even more crippling was the relentless inflation of game development costs. In 1994, the development team of Final Fantasy VI comprised only about 50 people and cost around $10 million; in 1997, the VII development team swelled to 150 people with a cost of about $40 million; VIII also set a record with a development team of 200 people. Starting from 1999, Square Enix had to maintain large teams in Japan and the United States simultaneously, and the development cycle also increased from 1 year to 2-4 years. Marketing expenses also continued to soar, necessitating simultaneous promotional campaigns in major global markets. Although Final Fantasy IX sold over 5 million copies, the return on investment was still low, which became a significant reason for Hironobu Sakaguchi's resignation.

Why did game development costs rise? Due to technological advancements, the transition from 2D art to 3D modeling brought about geometric changes; players' demands increased, necessitating continuous improvements in game content's length and depth. Crucially, Square Enix could not only scale back but must actively expand: investors expected the company to develop more IPs beyond Final Fantasy, and gold producers flocked to Square Enix, causing the company to pour resources into new projects. By 2001, the situation was irreparable: either cut peripheral projects, delay core projects, and conduct large-scale layoffs and restructurings, or face bankruptcy. The Final Fantasy series was crushed by its own success!

After nearly two years of arduous restructurings, the new 'Square Enix' was officially established in 2003. Now, the company owned two top IPs, Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest, and its production prowess was still at the forefront in Japan. However, beneath the seemingly glamorous veneer, it was no longer the original soul—early creators like Hironobu Sakaguchi, Yoshitaka Amano, and Nobuo Uematsu had left the company, and the management team was replete with newcomers who had no emotional attachment to Final Fantasy. Game technology was still advancing rapidly, and development costs continued to soar; online games had emerged as a new force and become the main growth engine of the gaming industry within just a few years. To tackle these challenges, Square Enix's strength was insufficient. Moreover, against the backdrop of a sluggish economy and a shrinking domestic market, the era of Japanese game companies calling the shots was over. A prolonged period of decline had arrived.

Struggling to Embrace Online Games, But Barely Keeping Up

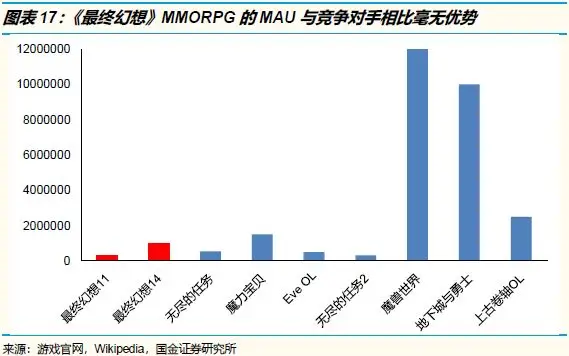

The first 10 installments of the Final Fantasy series were all single-player games, and the concept of online play did not exist at that time. However, Square Enix foresaw the future of online games very early on and announced in 2001 that Final Fantasy XI would be an MMORPG. At that time, the online game industry was still in its infancy, with only a handful of products on the market, such as Ultima Online, Stone Age, and even text-based MUDs. Theoretically, relying on the technological accumulation, IP popularity, and financial resources from the single-player era, Final Fantasy could naturally gain an edge in the MMORPG field.

However, reality did not align with expectations—Final Fantasy XI, released in 2002, sold only 2 million copies with a peak monthly active user (MAU) of about 300,000. The game received favorable reviews from the media: it adopted an instant battle system, emphasized teamwork, had a very rich job system, and featured multiple large expansion packs. Unfortunately, it was merely an 'excellent game' and not a 'groundbreaking masterpiece'; its innovativeness paled in comparison to same-era games like EverQuest, Eve Online, and the slightly later World of Warcraft. Overemphasis on teamwork excluded a significant portion of casual players. Although it achieved great success in Japan, its presence in the European and American markets was minimal.

Final Fantasy XI used Sony's PS2 and Microsoft's Xbox 360 as the primary platforms, and although there was also a PC version, it was not emphasized. Facts have proven that the main battleground for MMORPGs is the PC, and CrossGate, an MMORPG released by Enix during the same period, achieved immense success. To this day, players on game console platforms are still more accustomed to single-player games, weakly online games, and e-sports games, and they are not very enthusiastic about MMO games that require prolonged online sessions. Additionally, due to the mindset of the single-player era, Final Fantasy XI still maintained a buy-to-play payment system, greatly limiting the player base's size.

After learning from its mistakes, Square Enix launched Final Fantasy XIV in 2010, a time-based MMORPG. It became the biggest nightmare in Final Fantasy's history: despite its high technological level, the game's pace was too slow, the plot lacked interest, and the interface design was poor, leading to harsh criticism from players upon release. Some media outlets even believed that the golden brand of Final Fantasy might be completely tarnished! In 2012, Final Fantasy XIV was forced to shut down its servers and be rebuilt from scratch. In 2013, the completely revamped Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn was officially launched and achieved a certain degree of success, and it is still operational to this day.

Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn is a well-crafted, old-school, slow-paced MMORPG. Its graphics are top-notch among similar games, with a grand main storyline and abundant side quests, bearing a deep Japanese single-player RPG imprint. It is neither as eager to develop new concepts and gameplay as World of Warcraft nor inclined towards fast-paced gameplay to attract wealthy players like many competitors, but it is tailored for 'traditional RPG enthusiasts.' In the context of free-to-play games being prevalent, it adheres to the model of 'time-based subscription + cosmetic item sales.' In summary, this game is meticulously crafted and has a long lifespan, but it is destined never to become a colossal hit. On the Chinese servers operated by Shanda Games, the MAU may never have surpassed 1 million; the global peak MAU was only about 3 million.

Final Fantasy XI and Final Fantasy XIV are emblems of Square Enix's fate: in the single-player RPG era, it was the undisputed king and the object of imitation for all; in the MMORPG era, it was merely a formidable competitor that could only achieve limited commercial success and could not lead the trend. In this era, American companies represented by Blizzard possess strong technical prowess and financial resources, enabling continuous innovation; Chinese and Korean companies represented by Shanda, NetEase, and NCSoft have vast domestic markets and benefit from being early adopters of imitation. The golden age of Japanese game companies is over, and Japanese culture is no longer a globally dominant force. The gaming industry has never been an isolated sector but is closely intertwined with the overall economic situation and social changes.

The most alarming aspect is that the heyday of MMORPGs is waning, and we are now in the golden era of FPS, MOBA, SPT, and other e-sports games, with the potential for sandbox games to usher in their own golden age in the future. In the realms of e-sports and sandbox games, Japanese developers hold virtually no advantage. Square Enix is acutely aware of this crisis and has long attempted to diversify by producing fighting and action games under the Final Fantasy banner, but these efforts have merely served as temporary fixes. Ultimately, with a shrinking domestic market, waning technological prowess, and inadequate capital, Japanese developers are unlikely to achieve remarkable success in new game genres. As a result, companies like Square Enix are compelled to continue down the well-trodden path of traditional RPGs, relying on Japan's unique 'craftsmanship spirit,' despite the fact that mainstream gamers are no longer as impressed by this approach.

Caught in a quandary: if Final Fantasy cannot be the best, players will refrain from purchasing it.

While developing MMORPGs, the Final Fantasy series did not cease creating single-player titles: Final Fantasy X-2 in 2003, Final Fantasy XII in 2006, Final Fantasy XIII in 2009, and Final Fantasy XV in 2016 were all single-player or weakly online games. Additionally, single-player spin-offs such as Final Fantasy Type-0 and Final Fantasy Theatrhythm were also released. Most of these games featured some multiplayer and social elements. Unfortunately, Square Enix struggled even in its 'home turf,' especially after Final Fantasy XV, when the IP deteriorated significantly.

The battle system of Final Fantasy XII underwent radical changes compared to its predecessors: turn-based combat was replaced with real-time combat, and a complex 'command setting' mechanism was introduced, leading to an 'automation' trend in battles. The game's job system remained as deep and enjoyable as ever, with numerous side quests, mimicking MMORPGs. However, the game's main storyline was overly thin, allowing players to complete it too swiftly! Ultimately, Square Enix succumbed to 'cost phobia': to mitigate risks, it was necessary to control costs; the best way to do so was to limit game content, even at the expense of truncating the main storyline. But how can a single-player RPG that fails to tell a compelling story attract players? Despite high media scores, player dissatisfaction began to spread.

Final Fantasy XIII continued down the 'cost-saving' path: side quests were significantly weakened, scene details were sparse, and many daily battles were omitted. Players were essentially confined to the main storyline, which itself lacked appeal. While European and American developers focused on enhancing game freedom and establishing open worlds, Square Enix regressed. Thanks to the popularity of the Final Fantasy IP, the game still sold over 6 million copies, but its media reputation hit an all-time low, and its sales proportion in European and American markets declined.

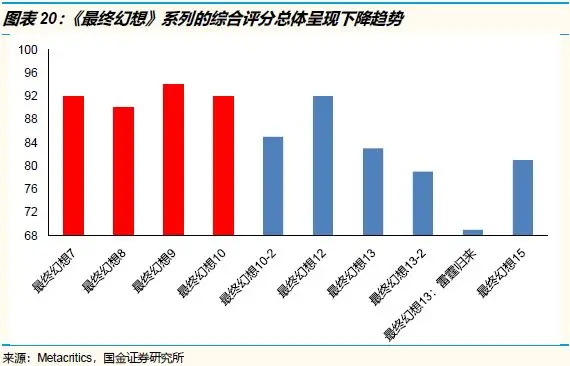

Encouraged by the decent sales of "Final Fantasy XIII," Square Enix decided to launch two sequels based on this game: "Final Fantasy XIII-2" and "Lightning Returns: Final Fantasy XIII." Sales of these sequels plummeted, and their reputation was even worse. Especially "Lightning Returns: Final Fantasy XIII," which was mocked by critics as "resembling an MMORPG tutorial chapter," achieved the lowest media score in the history of the Final Fantasy series. Among these three games, issues such as weak plot, inadequate game time, and low freedom persisted. In the minds of players, "Final Fantasy" is a sacred IP that must embody the pinnacle of RPGs; otherwise, it is deemed irrelevant. They will not accept a hastily developed and cash-grab oriented "Final Fantasy" game.

In truth, Square Enix put in considerable effort—the graphics, character design, and combat system of "Final Fantasy XIII" and its sequels were widely acclaimed, comparable to similar games from major European and American developers. The problem lies in the fact that Japanese game developers' strengths are no longer sufficient to balance both 'quality' and 'completeness': Producing an RPG with cutting-edge technology, stunning graphics, a compelling storyline, and substantial content entails immense costs and extremely high risks. After experiencing the bankruptcy crisis at the turn of the 21st century, how dare Square Enix repeat the same mistake?

The issues of excessively high costs and risks plague not only Japanese developers but also European and American ones. Mainstream European and American developers such as Activision Blizzard, EA, and Ubisoft have become increasingly conservative since the 2010s, either focusing on developing "annual products" with minimal innovation or striving to maximize game value through in-app purchases of props and DLC. Ultimately, these developers also fell into a vicious cycle of negative player reviews and diminished appeal of popular IPs. "Final Fantasy" is confronting a common challenge.

"Final Fantasy XV," released in 2016, might be the IP's "collapsing work": Despite decent sales and an acceptable media score, the plot was severely truncated, and freedom was extremely limited, rendering it almost a half-finished product. Clearly, the production team lacked the resources and courage to complete the game. Initially, players hoped that subsequent updates and DLC could "complete" the game; however, in November 2018, Square Enix announced that further development of the game was essentially over, shattering players' hopes. When an IP consistently disappoints fans, its end is near.

"Final Fantasy" Revelation: Will future generations mourn its decline without learning from its mistakes?

During the golden age of the "Final Fantasy" series, it scarcely resembled a conventional "IP." When the production company recognized the significance of "IP economics," this IP was already on the decline. Square Enix is not unaware of the importance of mobile games and has even proactively transformed into a "mobile game giant," but it has yet to complete this transformation. Ultimately, the gaming industry is a dynamic and ever-evolving sector—no one can make money by being complacent, and there is no universally applicable business model. One thing is certain: Players' demands for content are continually increasing. Today's powerful game giants may swiftly plunge into oblivion if they lack a sense of crisis.

The "Final Fantasy" series in its golden age was precisely the least like a conventional "IP"

Since 2014, "IP economics" has become a buzzword in China's cultural and entertainment market, with participants across various industries such as games, film and television, animation, and music exploring ways to maximize IP value. The question arises: What constitutes an IP? What is the secret to long-term monetization of popular IPs? The "Final Fantasy" series can be regarded as the first IP in the global gaming industry, still achieving high sales and influence even after years of decline. However, it is precisely the least like a conventional "IP" in the general perception.

Until 2003, there was no connection between the plots, characters, and worldviews of previous "Final Fantasy" titles. That's right; regardless of the success of the previous "Final Fantasy," the next one would start anew. We wouldn't see any protagonist reappear, nor any continuation of the story. So, how was the "Final Fantasy" series coordinated? This involves the so-called "tone" or "style." Firstly, the backgrounds of all official "Final Fantasy" works are exceptionally grand and harsh—huge evil forces seek to destroy the world, and weak protagonists strive to grow and defeat them through arduous struggles to restore balance. Each work is an epic worthy of song and tears, captivating players and delivering a profound spiritual impact.

Secondly, the "Final Fantasy" series often delves into humanity's ultimate questions: life and death, man and nature, love and hatred, oppression and resistance, technological progress and tradition... The 7th generation depicts a "dystopian" society controlled by large technology companies, the 8th generation deeply discusses the shaping effect of memory on humans, the second half of the 9th generation's plot revolves around "the meaning of life," and the 10th generation portrays "breaking the cycle of death with sincere love." For pure entertainment players, these plots may seem too heavy; however, precisely because of their depth, they leave room for contemplation and repeated pondering. Strictly speaking, the primary audience of the "Final Fantasy" series are adult players with certain life experiences; moreover, as they age, they repeatedly revisit and relish this series.

Furthermore, the "Final Fantasy" series shares many common details: Almost every game features golden chocobos and airships for rapid player movement; summon monsters appear in each generation, with certain commonalities in their names and attributes. During combat, players always hear the same music; the end-game music remains unchanged. Many secondary characters share the same names throughout the series. Veterans of the "Final Fantasy" series can determine if a game belongs to the series within half an hour of starting it. In summary, the IP attributes of "Final Fantasy" are not inherited through characters or plots but through "content tone." This is a double-edged sword: Each work is novel and offers immense room for creativity; however, it's challenging for the fan base of previous works to be directly inherited, and the workload of recreation is substantial.

In 2001, under the pressure of bankruptcy, Square decided to break tradition and develop a sequel to "Final Fantasy X," which was "Final Fantasy X-2" released in 2003. The tragic ending of the original work caused dissatisfaction among many fans, and Square was eager to leverage the character and scene design of the original for secondary monetization. Consequently, "Final Fantasy X-2" achieved commercial success and opened Pandora's box—Square became increasingly eager to exploit IP popularity to "reheat old rice" rather than innovate. Since then, sequels to the 12th, 13th, and 15th generations have been launched, and even sequels to the 4th and 7th generations released many years ago have been revived. Some of these sequels were successful, but most overdrew the IP value. In short, when the production company realized that "IP economics" is a lucrative path, the "Final Fantasy" IP embarked on the journey of "living off old capital."

In the eyes of some investors, IP is a lazy tool that can turn stones into gold and decay into magic. However, fans will not unconditionally support any IP, and all monetization efforts come at a cost. Exhausting resources is certainly not a viable option. In reality, IP should only be used to "add flowers to the brocade"—when the production team is passionate, experienced, and technically proficient, a high-quality IP can enhance their efficiency. Throughout the 1990s, the "Final Fantasy" production team led by Hironobu Sakaguchi continually innovated and accumulated new capital for this IP, rather than "living off old capital"; they even deliberately developed several new IPs with different creative visions. When Square decided to develop "Final Fantasy X-2," Hironobu Sakaguchi chose to leave the company. He knew better than anyone that destroying an IP is far easier than creating one, and any compromise on principled issues leads to doom.

Square Enix, now a "pseudo-mobile game giant"

Since the launch of the iPhone in 2007, smartphones have emerged as a significant gaming platform. Currently, most of the growth in the global gaming market stems from mobile games, overshadowing traditional console and PC platforms. Many traditional European, American, and Japanese manufacturers have missed this mobile gaming wave, but Square Enix is an exception—it has enthusiastically embraced the mobile game market since 2007, independently developing and licensing numerous "Final Fantasy" themed mobile games. Simultaneously, it has ported many official "Final Fantasy" titles to the mobile platform.

Given Square Enix's enthusiasm for mobile games, many players have dubbed it a "mobile game giant." However, its success in the mobile gaming realm has been modest, and it can at best be considered a "pseudo-mobile game giant." Firstly, until 2017, the company was still indecisive between the "paid model" and the "free model," despite the "paid model" proving unsuitable for mobile gamers. "Final Fantasy XV Pocket Edition" was tailor-made for the mobile platform but still adopted the "free first chapter + paid subsequent chapters" model. The result was dissatisfaction on both sides: Traditional players believed that the mobile game version tarnished the IP tone of "Final Fantasy XV," and mobile gamers were not accustomed to paying for story chapters.

Certainly, Square Enix has experimented with the "free download + in-app purchase of props" business model, with "Final Fantasy: Brave Exvius" launched in 2015 being the most successful example. Set to be introduced to China by Xishanju in 2018, this game stands out amidst a sea of mobile titles that have either floundered or met with mediocre success. Our observations reveal that roughly one-third of "Final Fantasy"-themed mobile games released before 2015 have ceased operations, with the majority only achieving commercial success in Japan or a select few countries. Due to Square Enix's limited development capacity, it often licenses third parties to develop these games, which complicates quality control. For instance, "Final Fantasy XV: A New Empire," developed by a third party in 2017, received overwhelmingly negative reviews.

Even when mobile games boast high production quality, the popularity of the "Final Fantasy" IP has waned, making it difficult for these titles to sustain popularity on their own. In China, for example, mobile gamers are eagerly anticipating European and American blockbusters like "Diablo," "World of Warcraft," and "FIFA," as well as classic IPs from China and South Korea such as "JX Online III," "Stone Age," and "Perfect World." Despite the decent quality of "Final Fantasy: Awakening," an ARPG mobile game developed by Perfect World in late 2016, it lingered in the top 100 of the iOS best-selling list for less than two months.

Assuming Square Enix could muster a strong R&D team or identify a suitable third-party developer to create a top-tier "Final Fantasy" MMORPG, its performance in the Chinese market would likely mirror that of "Langrisser" or "Cross Gate" mobile games: ranking highly in the best-selling list for the first 1-2 months before rapidly declining. In European and American markets, MMORPGs have never been the most popular mobile game category, making it challenging for the "Final Fantasy" series to become a hit. While the series remains highly popular in Japan, the mobile gaming market there is already quite limited. In summary, the likelihood of "Final Fantasy" reclaiming its former glory through mobile games is slim.

"Final Fantasy XV Pocket Edition," released in 2017, serves as an awkward attempt. While it boasts a high degree of completion and has garnered media praise and App Store editor's recommendations in various countries, its total download volume of only 3 million, with approximately 2 million paid downloads, falls short of commercial success. Eventually, Square Enix ported this game back to game consoles and PC platforms, as players on these platforms offer higher ARPU values. These peculiarities indicate that Square Enix has yet to master the development and operation of mobile games, unlike its counterparts in China and South Korea who, despite having weaker historical foundations, have better adapted to this era.

In the gaming industry, constant change is the only enduring theme.

For years, investors have sought ways to effortlessly profit in the gaming industry: through channel control, repeated IP value extraction, the "free + in-app purchase of props" business model, large-scale data patches, DLC, and other content overlays, or by emphasizing the social and esports attributes of games. While these methods have some effectiveness, their sustainability is questionable. In the 1980s, Nintendo, which controlled global game distribution, failed to achieve effortless profits; similarly, Tencent, which dominates Chinese game distribution today, faces the same challenge. Change is the only constant.

Since 2013, the mobile game industry has experienced explosive growth globally, particularly in China. In November 2018, Blizzard proudly announced "Diablo: Immortal," a mobile game developed jointly with NetEase, but immediately faced backlash from players, leading to a drop in Blizzard's stock price. The reason is straightforward: mobile games are not for everyone, especially not for hardcore gamers in Europe and the United States. The prevalent "skin-changing mobile games" in China have left a negative impression on Blizzard fans. Moreover, the era of players paying solely for a popular IP is over. In the Chinese market, popular IP adaptations of mobile games launched in 2018, such as "MU: Origin," "Cross Gate," and "Legend of Mir 3D," were also short-lived.

The mobile platform presents some fundamental issues: its limited operation methods and touchscreen interface are unsuitable for more complex game genres like action and shooting; hardware diversity makes it difficult for game developers to optimize for all mobile phone models; and the small device size and limited battery life are inherently unsuitable for large-scale, engaging games. Most importantly, smartphones are not designed for gaming and cannot compromise too much for gaming purposes. So, what is the solution?

Nintendo's answer is the Switch, a console with strong "mobile functionality" released in 2017. Nominally, the Switch is a "combination of a game console and a handheld console"; in reality, it is more akin to a "hybrid of a console and a mobile phone." Its tablet-like size, touchscreen design, detachable joysticks, comprehensive online functionality, emphasis on social interaction, and multiplayer collaboration all echo mobile gaming. Tencent even decided to port "Arena of Valor," the overseas version of "Honor of Kings," to the Switch, sparking controversy among players. If this trend continues, we may witness the complete integration of game consoles and mobile phones within a few years. No one knows what blockbuster games will look like at that time.

Another critical issue is the escalating cost of game development, with even mobile game development entering the "burning money" era. If this trend persists, only a handful of large companies will be able to develop blockbuster games, significantly narrowing players' choices and stifling innovation. This phenomenon is already evident on console platforms. On PC platforms, Steam has played a pivotal role in supporting independent games and promoting the monetization of niche games, delivering numerous innovations to the gaming market. Tencent's WeGame aims to replicate this success in China. In the mobile game market, developing niche markets, maintaining a thriving scene, and uncovering the creativity of the next blockbuster from niche products are common challenges faced by mainstream publishers. In this creativity-driven industry, the absence of new categories and gameplay mechanics spells doom.

For over a thousand years, Roman conquerors returning from war were honored with a triumph: a raucous celebration. During this ceremony, trumpeters, musicians, and exotic animals from the conquered territories would parade, accompanied by carriages laden with treasures and captured weapons. The conqueror would stand in a triumphant chariot, preceded by a procession of stumbling prisoners of war. Sometimes, the conqueror's children would stand beside him in white robes or ride on the horses pulling the chariot. Behind the conqueror, a slave would always hold a golden crown, whispering a somber reminder: "Remember, all glory is fleeting."