When AI Invades Your Phone, Unleashing the 'Eyes of God'

![]() 11/10 2025

11/10 2025

![]() 551

551

As I lounged on the sofa, finally getting over the awkwardness of talking to myself, I barked at my phone's AI assistant, "Braised chicken with rice." The screen of my newly acquired phone flickered as if real fingers were swiping across it, gradually opening the delivery app's storefront. I stared blankly for about five seconds as several nearby restaurants popped up for me to choose from.

This AI can do even more for me. For instance, it can craft Xiaohongshu (Little Red Book) posts, though the writing is rather pedestrian; it can scan my WeChat chat history to set up schedules; and it attempts to remember my habits and recommend various functions.

While marveling at its capabilities, I suddenly realized that all my information on the phone was laid bare before the manufacturer. My operating habits and the data left in various apps were all being monitored by the phone. Then, it guessed what I wanted based on my information. Although the functions are still quite basic, the scope of information it gathers is expanding, and the destination of the data captured by large models remains unclear. This realization sent a shiver down my spine.

It wasn't always like this. Phone manufacturers weren't permitted to do this before.

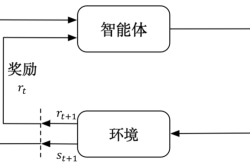

Both Apple's iOS and Android systems feature built-in 'App Sandbox Isolation Mechanisms' to prevent apps from accessing each other's data, as well as 'Permission Control Frameworks' to restrict phone manufacturers from accessing sensitive information without user consent. However, the AI assistants pre-installed on phones from these manufacturers have quietly opened the 'Eyes of God' for their AI by leveraging a system-level permission—accessibility service permissions. This enables them to simulate cross-app operations and activate 'God Mode.'

Accessibility services are highly sensitive permissions designed specifically for people with disabilities, allowing them to use screen readers to 'hear' screen information and utilize automatic clicks to reduce manual operations.

This permission has rapidly expanded the application scenarios for phone companies' AI assistants but has also left users' phones vulnerable, potentially breaching the final barriers of privacy data and financial security.

Why are these phone companies so audacious as to delve into users' forbidden zones?

The new phone market continues to shrink, with new entrants like Google and returning veterans like Meizu and ZTE intensifying competition, heightening survival anxieties and the risk of industry shakeouts.

There is also a sense of crisis stemming from the highly disruptive nature of AI technology. "In five years, phones and apps will be obsolete," predicted Elon Musk, who added that all interactions will be generated, predicted, and completed in real-time by AI. His latest controversial remark sent ripples through the entire mobile industry.

Additionally, AI assistants that have accessed 'God Mode' through accessibility channels provide phone companies with more means to manipulate the software ecosystem for monetization, such as traffic distribution.

Faced with this sense of crisis and the allure of profits, as well as the convenience offered by customized system permissions, many phone manufacturers have chosen to take risks, leaving users with virtually no choice.

Phone Companies Activate 'God Mode'

From the application ecosystem to the capital market, AI has profoundly transformed the face of today's internet industry.

The cost of AI computing power has plummeted, with the price per million tokens dropping from over a hundred dollars at the beginning of the year to just a few yuan in Renminbi, thanks to Deepseek. On this basis, the AI process has accelerated comprehensively, with innovations in AI-driven application and functionality reconstruction, as well as hardware, emerging endlessly.

OpenAI launched Sora, an AI video generation application, and ventured into browsers. ByteDance is busy enabling its Doubao AI to 'add links,' while Alibaba's Quark is moving into AI glasses.

Phone manufacturers are not far behind, launching their own AI phones and attempting to reconstruct products and even the entire mobile industry value chain from hardware, systems, to applications using AI innovation.

'One-sentence operation' is becoming a key marketing highlight for phone manufacturers. With just one sentence, the phone's intelligent agent can complete complex tasks like booking tickets, ordering food, and canceling subscriptions across multiple apps.

From product launch demonstrations and presentations, the imagination packaged in AI interaction has become a new selling point. Through frictionless design, it constructs a layer of static screen-perceived intelligence, enabling multi-step reasoning, contextual understanding, and cross-platform operations.

However, in actual implementation, the low accuracy caused by AI hallucinations and the operational delays in 'screen reading' simulated clicks often significantly reduce the efficiency of such operations, while the security risks remain undiminished.

From a technical standpoint, many current AI assistant functions are achieved by using the 'accessibility channel' originally developed for people with disabilities in the Android system. When you order a cup of coffee, the phone assumes you are disabled and reads the information on your screen, clicking step by step on your behalf. When you manage your work schedule, it reads your information across various apps and directly hands it over to a large model for analysis and operation.

Regarding the exploitation of this accessibility channel, I have seen cybersecurity experts warn—accessibility functions primarily grant phone intelligent agents three capabilities: first, the ability to read all content on the screen, including bank card information, special password keyboards, and chat records, not just specific data. Next, the ability to simulate interactive actions like clicks, swipes, and inputs, enabling it to operate the phone like a human finger. Finally, cross-app control. Accessibility functions act as a universal access card, bypassing the isolation between different apps and calling up the required content across programs.

This capability is known as 'God Mode.'

Sometimes, users are not even notified when these permissions are activated. According to tests by authoritative media organizations, phone AI intelligent agents have numerous complex service agreements, with manufacturers like Vivo not clearly stating which AI functions will invoke accessibility permissions.

OPPO explicitly states in its personal information protection policy that Xiao Bu Screen Recognition will invoke accessibility services and does not ask for permission before enabling it, nor can users disable it.

Moreover, third-party large model companies have also caught wind of the business opportunity. Zhipu's 'Cloud Phone'—AutoGLM, which carries a large number of apps, allows one-sentence operation of over 40 apps, including Douyin, Xiaohongshu, Meituan, and JD.com, after logging in. This may further exacerbate the risk of terminal manufacturers abusing accessibility permissions.

At this critical juncture where AI invades personal space, the large-scale introduction of powerful 'invasive AI' without transparency inevitably raises concerns that it will harm users' long-term interests and trust over time.

The Data Black Box of Invasive AI

"Apple's privacy policy states that the company can only share user information with explicit user consent." This full respect for user privacy has provided Apple users with security and earned Apple their loyalty.

The disregard for user privacy and the application ecosystem are, in fact, mutually causative. The aforementioned on-device AIs share a common trait: they invade third-party apps without authorization, reading and using their user information, posing significant privacy and data security risks, collectively referred to as 'invasive AI.'

The risks involved in AI screen reading and AI-assisted operations by this invasive AI essentially require addressing two major concerns: where the data comes from and where it goes.

The longer the data transfer chain, the greater the risk of leakage.

From a data transfer perspective, the computing power limitations of on-device models make data uploading to the cloud inevitable. However, uploading large amounts of screen-reading data to the cloud without proper solutions is tantamount to data running naked.

Moreover, the data often needs to be shared with third-party large model companies, whose privacy policies are usually more lenient, further amplifying the risk of sensitive information leakage.

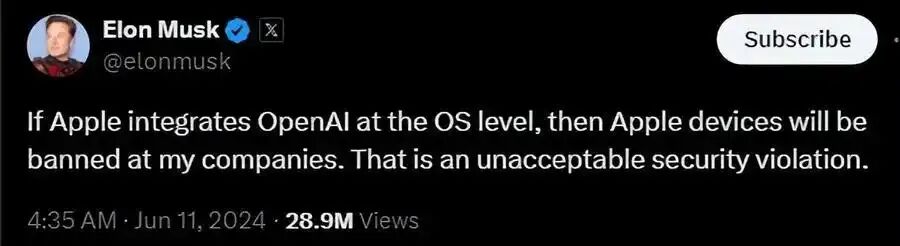

Elon Musk directly pointed out, "If Apple integrates OpenAI into its operating system, the company will ban the use of Apple devices. This is seen as an unacceptable security violation."

It is evident that this invasive AI disrupts traditional privacy protection and data security orders. How should the related security responsibilities be divided and who should bear them? The invasive AI application, the invaded application, or the third-party large model company?

This invasion risk has gradually surfaced. Xinhua News Agency reported a real case in March this year where fraudulent apps like 'Zhongyin Conference' and 'Douyin Conference' used the 'screen sharing' function to see all the victim's operations on their phone, including bank card account numbers, passwords, verification codes, and even directly control the victim's phone to complete fraudulent transfers.

Additionally, I saw a post by a user on Xiaohongshu stating, "I felt a chill down my spine when I used AI screen sharing to help my little niece write an essay. The AI-polished essay actually included the name of my residential area! The blogger thought it was a paranormal event but later realized that the information was in their group chat name. They were just lucky that no other information was leaked."

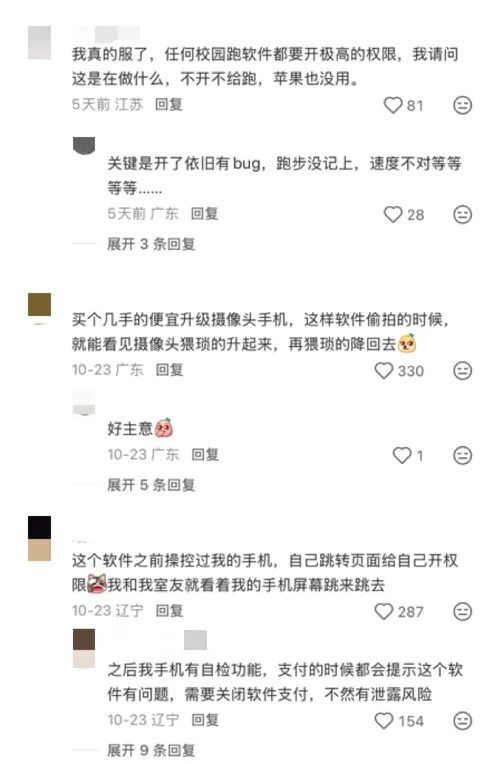

Furthermore, when searching for information on accessibility permissions, I came across complaints from college students on social media about a sports app required by their school, which demanded accessibility mode authorization to 'claim benefits.' The result was endless advertisements, with some users commenting that they saw their phone screen operating by itself in the middle of the night!

If these risks spread, they will only hinder the progress of our AI industry, turning supposed shortcuts into detours.

The evolution of interaction methods is irreversible, but it also requires the gradual construction of infrastructure from hardware and software to standards. Putting in hard work to establish industry-wide collaborative standards that balance user security and industry ecology is the long-term solution.

From the European and American markets, we see that interactions between AI applications do not have to rely solely on the accessibility channel model. The protocol model represented by MCP actually provides a safer approach, typically using clearly defined framework agreements, explicit tool integration, and clear action scopes for sandboxing. This may be a more responsible innovation path for users and the industry.

It's never too late to mend. Since this spring, domestic efforts to regulate 'screen reading operations' by intelligent agents have intensified. Today, when risks have not yet spread widely, it is precisely the window of opportunity to take proactive measures.

Phone Companies 'Monetize,' Users Pay the Price

In the fierce low-price competition for hardware, many phone companies have chosen to seek profit margins in the user ecosystem. Many manufacturers have already extended their reach into the software ecosystem, engaging in pre-installation, channel revenue sharing, advertising, and even consumer finance.

Invasive AI is merely a new means for phone companies to monetize the mobile internet ecosystem. Once they rely on selling user traffic as their primary profit source, phone manufacturers find themselves in opposition to their own phone ecosystem.

Acting as both referee and player, this internal conflict also leads phone companies to over-rely on ecosystem profits rather than brand premium and system experience, which remain difficult to improve over the long term.

Forcible monetization tactics also disrupt the distribution of applications and AI services.

Many users often encounter situations where downloading apps from their phone's built-in app store goes smoothly, but downloading from third-party app platforms like 360 Mobile Assistant, App Treasure, TAGTAG, or Wandoujia frequently triggers 'risk warnings,' leaving consumers facing the dilemma of 'unable to download desired software while being bombarded with unwanted recommendations.' This type of 'system interception' hijacks user traffic at the information level, infringing on consumers' right to choose.

This excessive exploitation in app distribution has also provoked a fierce backlash from app developers.

Recently, many netizens have posted about multiple NetEase games ceasing operations on OPPO's channel server. As early as November last year, NetEase's 'Onmyoji: Yokai House' announced the discontinuation of its OPPO channel version, followed by several other NetEase games. Entering 2025, more games have ceased operations on OPPO.

Industry analysts suggest that this may be related to the traditional high revenue-sharing model in the Android channel for the gaming industry, with sharing ratios reaching up to 50%, significantly higher than the international mainstream of 30%.

Meanwhile, small and medium-sized developers overseas have also suffered from Apple's commission fees, but this situation is quietly changing. EU penalties against Apple have broken the long-term monopoly of the Apple App Store and Google Play, leading to a surge in the number of third-party app stores in the EU to 47 within a year.

In contrast, the rapid advancement of AI in China has given domestic phone manufacturers leverage to further monetize the software ecosystem.

The AI systems integrated by multiple phone manufacturers have already secured spots among the top 10 in terms of user growth for AI-native applications. AI is not only perceived as a pivotal success factor in the hardware market but also as a remarkable gateway for transforming the software ecosystem landscape and reaping substantial profits.

Apple, Huawei, Vivo, and OPPO have all unveiled their respective intent frameworks. Nevertheless, the ability to invoke atomic services and the sequence of such invocations hinge on the manufacturers' partnerships and profit-sharing agreements, rather than the quality of the services themselves. This situation has, from the very beginning, distorted the incentive mechanism for innovation within the AI ecosystem applications, inevitably leading to a scenario where inferior products prevail over superior ones.

After all, the stakes are immense. The running app that the aforementioned college student lamented about, which activated accessibility mode, was followed by a flood of pop-up ads and extremely rapid depletion of battery and data. All these factors contribute to profit generation.

On-device AI in phones has garnered a significant competitive edge by exploiting accessibility functions, which translates into advertising revenue from service and traffic distribution, as well as commercial advantages.

As the controllers of the underlying system, phone companies exploit system-level permissions to aggressively promote intrusive AI while simultaneously restricting the avenues for third-party apps to acquire users through interception tactics. This systematically diminishes the survival space for small and medium-sized apps.

More critically, users' right to privacy and their legitimate right to 'choose their own app acquisition channels' are being brazenly violated.

Phone companies ought to find their proper place within the ecosystem. If they engage in low-price hardware competition and anticipate retaining users through excessive manipulations, they have already lost strategic focus. Moreover, if they infringe on user privacy for short-term gains and disrupt their software development ecosystem, how can they possibly compete in terms of application experience?

Such overreach and unwillingness to stay within appropriate bounds should be minimized.

As Steve Jobs once articulated, we should have 'the freedom from being invaded by certain programs' in terms of privacy, the freedom from having our batteries drained by certain programs.' We should also possess the freedom from being coerced into using certain apps or services, the freedom from being invaded by this type of intrusive AI filled with interest exchanges, which compromises our privacy and even asset security.

Only when these freedoms are respected and addressed can the new world of AI be constructed on a broad and solid foundation, rather than on shifting sands, ultimately avoiding a futile endeavor.