The 'Money-Burning War' Among Sino-US Tech Giants Erupts Again: Who Has Calculated the Costs of AI Investment?

![]() 02/10 2026

02/10 2026

![]() 569

569

AI commercialization is turning into an increasingly expensive 'dinner party'.

During the 2026 earnings season, AI spending has not become a moat for tech stocks but rather a trigger for valuation declines.

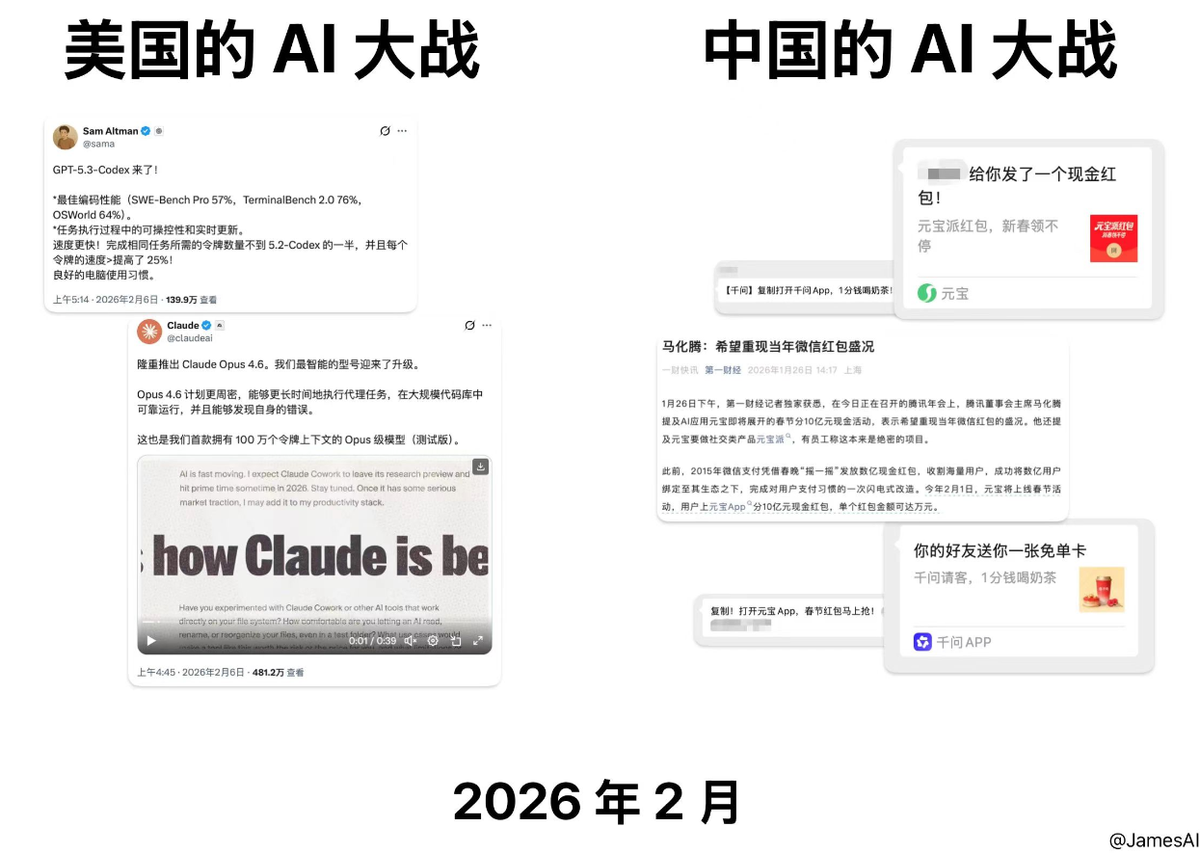

On one side, giants like Amazon, Google, and Microsoft have announced combined annual capital expenditure plans exceeding $650 billion, a scale comparable to the GDP of a medium-sized country. On the other side, Chinese internet giants have intensively launched billions of yuan in AI application subsidies around the Spring Festival, attempting to use 'red envelopes' to acquire market share, time, and user habits.

However, the capital market's reaction has been remarkably consistent. After the aggressive spending plans were announced, the stock prices of these tech giants fell sharply.

Figure: Stock Price Trends of Microsoft, Amazon, Tencent, and Alibaba

Is the market suddenly bearish on 'AI'? Not quite. However, investors are explicitly stating for the first time that they will no longer unconditionally pay for 'long-term investments without a clear path to realization.'

Whether it's the U.S. bet on computing infrastructure or China's push for application subsidies, the logic of this escalating AI competition—'burning money to preempt (seize) future markets'—recalls the 'food delivery/ride-hailing wars' of the past. But the problem is that this war may not have the premise that 'scale equals victory.'

Technological innovation dressed in the 'new clothes of food delivery' does not equate to a good business.

The AI narrative has shifted from 'fear of missing out' to 'fear of spending.'

Over the past two years, the core logic of the capital market paying for the AI narrative has been 'secure a position and layout first,' with valuations more closely tied to imagination.

But entering 2026, the situation has taken a sharp turn. The era of indiscriminate investment where 'anything AI-related rises' has ended, and the market has begun to focus intensely on two of the most realistic financial metrics: free cash flow and the irreversibility of capital expenditures.

For example, over the past 12 months, Amazon's free cash flow was only $11.2 billion, a significant 70.7% decline year-over-year. Its $200 billion capital expenditure plan for 2026 has raised market concerns that its free cash flow may return to negative territory.

AI is no longer just a charming growth story; the market is paying attention to the 'heavy assets, long depreciation, and low flexibility' of infrastructure for the first time.

Meanwhile, the new round of application subsidy wars in China has also revealed a striking similarity in the capital logic of this global tech competition to the past 'food delivery wars.'

The similarity between the AI competition and the food delivery wars lies not in business models but in capital logic.

First, there is the mindset of 'pre-pricing,' which involves seizing pricing power in future markets through massive investments before demand is fully validated.

Second, there is the competition for 'entry points' and 'ecosystems.' Whether it's U.S. giants investing heavily in data centers and self-developed chips or Chinese companies subsidizing developers and applications, the ultimate goal is to compete for control over the future AI world.

Finally, there is the implicit expectation of a 'winner-takes-all' outcome, with capital believing that under such high barriers, only a few oligopolies controlling infrastructure or core ecosystems will remain.

However, the market is concerned that AI lacks two critical prerequisites of 'food delivery.'

First, AI lacks a 'high-frequency, rigid demand' foundation.

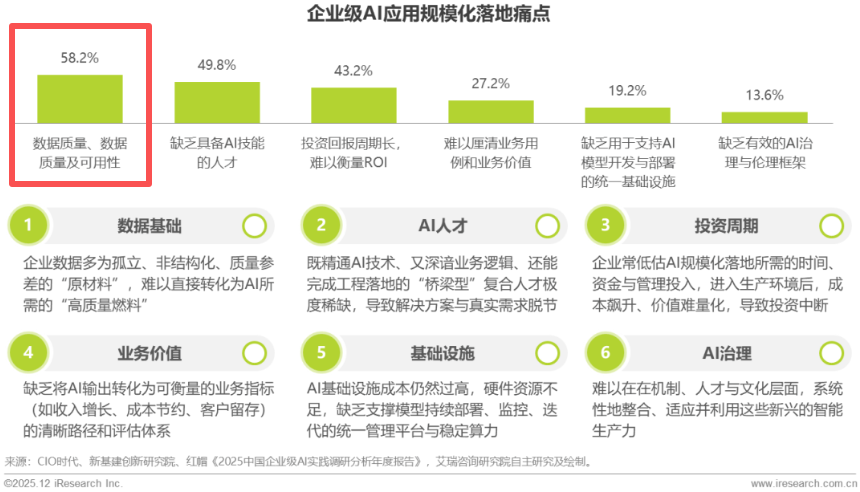

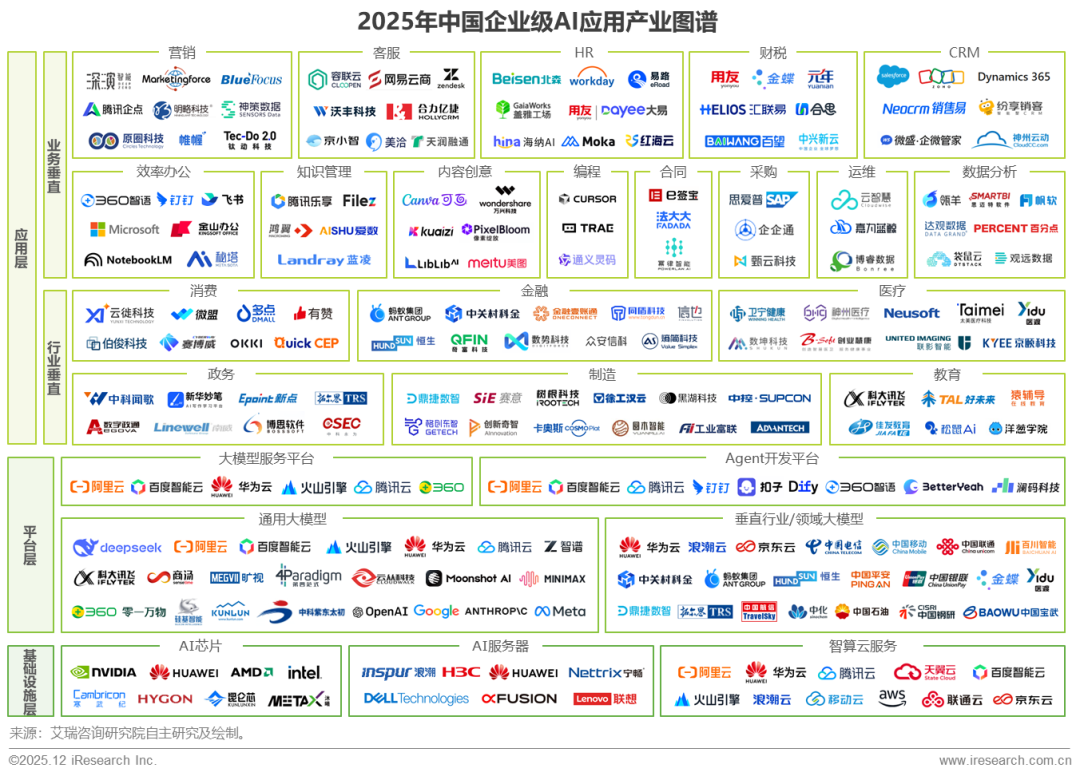

Food delivery is a confirmed high-frequency, rigid demand, and subsidies can quickly validate retention and repurchase rates. In contrast, the 'rigid demand' for AI remains extremely unclear. The success rate of large-scale model deployments for enterprise clients is still low, with iResearch surveys showing that over half of enterprise-level AI applications suffer from insufficient data quality and usability. Meanwhile, C-side users, long influenced by the internet's 'free + premium service' model, have low awareness and willingness to pay.

Second, and more dangerously, AI's massive investments are highly irreversible.

Food delivery subsidies can be adjusted, scaled back, or even halted at any time, offering relatively flexible business leverage. However, AI investments, especially infrastructure represented by data centers, server clusters, and custom chips, are highly sunk costs. These assets not only have extremely high unit costs but also carry long depreciation cycles, typically three to five years. Even if future demand falls short of expectations, companies will find it difficult to 'hit the brakes' and stop losses as quickly as shutting down a food delivery business.

When the two critical safety nets of 'high-frequency, rigid demand' and 'rapid loss mitigation' are absent, the capital market's cautious psychology is amplified.

It is at this juncture that Sino-US tech companies have demonstrated entirely different approaches to this caution.

Billion-Dollar Subsidies vs. Trillion-Dollar Infrastructure: Two Beliefs, Two Risks

In early February, the valuations of Sino-US tech stocks Synchronized callback (synchronized corrections), but behind the market sell-off lie two entirely different types of concerns. One is skepticism about whether 'limited spending' can deliver real value, while the other is fear that 'endless spending' could devour all cash flows.

This difference arises because the strategies of Sino-US tech giants are not aligned.

Figure Source: Internet, with thanks to the original author JamesAI

After discovering a broad but empty road, the core logic of Chinese companies is that 'demand can be quickly created and validated.' Thus, domestic giants are both building the road and manufacturing the vehicles.

Resources from giants like Alibaba, Tencent, and ByteDance have been intensively directed toward subsidizing developers, distributing user red envelopes, and providing computing power support. On the existing AI 'road network,' they are rapidly deploying 'vehicles' (AI applications) through massive subsidies to compete for C-side 'traffic control rights' and user habits.

The market's doubts lie here as well. When the red envelope rain stops and computing power discounts fade, how much of the attracted traffic will translate into real user retention and willingness to pay? A consensus in the industry is that getting users to pay directly for C-side AI tools is extremely difficult in the Chinese market. This battle questions whether AI applications themselves are 'pseudo-demand.'

In contrast, U.S. giants on the same road have chosen a more thorough 'infrastructure gamble': building more luxurious 'highways' a decade in advance, waiting for the entire digital economy's 'traffic' to naturally migrate there.

Capital expenditures by Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and Meta are highly focused on the computing power base—data centers, self-developed AI chips, and cloud platforms. They are building barriers from the 'infrastructure control rights' downward, believing in a deterministic future: AI will become an indispensable general-purpose technology platform for society, just like electricity and the internet.

In response, the market questions whether this trillion-dollar infrastructure will long-term drag down cash flows and return on investment if AI does not become a 'necessity' as expected.

From these different angles of skepticism, it is clear that there are enormous differences in the industrial genes and market environments of Sino-US tech, which also means intensifying valuation divergences.

The Chinese internet industry has undergone multiple traffic wars and excels at using agile product and scenario innovations to force demand through rapid trial and error. In contrast, U.S. tech companies have followed successful experiences from operating systems to cloud computing, habitually building powerful underlying platforms and standards first, then waiting for ecosystems to prosper.

The former is a 'present continuous' prioritizing application efficiency, while the latter is a 'future perfect' prioritizing infrastructure. This determines that the capital market's revaluation of the two will not converge at the same endpoint.

For Chinese companies, the valuation anchor is the efficiency and speed of application conversion. For U.S. giants, the valuation anchor is the discounted calculation of long-term dominance and return on investment.

Beneath the surface of falling stock prices, a divergence in technological routes and business philosophies is just beginning to unfold.

The Faith in 'Spending as Righteousness' Wavers, and Hong Kong Stocks Become a Key Intermediate Zone for AI Revaluation

What can be foreseen is that after this earnings season, a generational valuation divergence is taking shape.

Suspicion in the U.S. stock market about whether 'AI justifies building so many roads' will persist for a long time. Meanwhile, the Hong Kong stock market has become a key arena for reassessing whether 'any vehicles are actually running' on AI applications.

In the U.S. stock market, tech giants will face long-term revaluation.

The market's fear is not AI's potential but the 'time frame' and 'economics' of its disruption to traditional business models and ability to generate economic benefits. Morgan Stanley reports estimate that global AI-related spending will approach $3 trillion by 2028. Calculated at typical software profit margins, AI software revenue will reach $1.1 trillion in 2028, leaving a significant gap.

Once the massive capital expenditures of companies like Microsoft, Google, Amazon, and Meta are initiated, they are largely irreversible, with cash flows and balance sheets being reshaped by AI investments for the long term. If the climb of AI demand curves is slower than the erosion of depreciation curves, the market's 'valuation kill' on these tech giants will continue.

Recently, Microsoft's forward P/E ratio dropped to 23.0x, even lower than IBM's, which is software and services-centric. This is the first time since 2013 that such an inversion has occurred. It suggests that in investors' eyes, a 'new Microsoft' burdened with heavy depreciation costs may be undergoing a 'permanent heavy-asset transformation,' with pricing logic becoming increasingly 'heavy.'

In contrast, the current revaluation of Chinese companies exhibits more distinct stage-specific validation characteristics.

The 'red envelope subsidy' tactics during the Spring Festival involved relatively controllable investment scales and shorter trial-and-error cycles. Market feedback will reflect rapidly and directly in stock prices, like tides.

This makes the Hong Kong stock market the 'eye of the storm' for observing the success or failure of China's AI strategy. What unfolds here is a 'midfield battle' over application efficiency, user retention, and willingness to pay. The Hong Kong stock market also has numerous AI application companies that will be driven by the revaluation effects of giants, with valuations fluctuating in vertical scenarios based on commercial conversion efficiency.

This logic of 'small-cycle revaluation,' together with the U.S. stock market's 'long-cycle pricing' based on decade-long infrastructure returns, constitutes the capital blueprint for AI industrialization.

The coexistence of these two revaluation logics also means that the AI industry is moving from its first half to its second half. Giants are gradually burning through the capital market's patience for 'future narratives,' and as global capital grows weary of 'grand narratives,' 'the ability to deliver results' itself has become a scarce asset.

For the capital market, this means that more and more AI companies do not need to prove they can dominate the entire AI world like giants. They only need to prove that their products can create sustainable commercial value in specific scenarios, such as healthcare, marketing, or design, to achieve value realization.

History has repeatedly shown that the winners of technological revolutions are not necessarily the earliest, most aggressive, or most cash-burning companies. Those adept at converting technology into stable cash flows often navigate the ups and downs of cycles to secure a place.

Source: Hong Kong Stocks Research Society