Computing Power Race (Part 1): How GPUs Transform into the New Oil of the AI Era

![]() 02/10 2026

02/10 2026

![]() 427

427

Author | Qianyanjun

Source | Bowang Finance

At the turn of the year, the spotlight of China's capital market has never been so intensely focused on the banks of the Huangpu River. A formidable "GPU whirlwind" is sweeping in: within less than a month, three Shanghai-based GPU companies—Maxwell Technologies, Biren Technology, and Iluvatar CoreX—have made consecutive listings in the capital market. Suiyuan Technology, which is grouped with them as the "Four Little Dragons of Shanghai GPUs," has also completed its IPO counseling and is about to complete the final piece of the puzzle for this grand event.

From the wealth creation myth of a 692.95% surge on the first day of trading on the STAR Market to the astonishing subscription record of over 2,300 times on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange; from IPO fundraising scales in the tens of billions to the batch [Note: ' batch ' is translated as 'batch' to convey the idea of multiple companies entering the 'club'] batch birth of companies with market capitalizations in the hundreds of billions, domestic GPU companies are declaring the arrival of a new era in the domestic computing power industry with their aggressive capital offensives.

This is no by chance [Note: ' by chance ' is translated as 'accidental' to fit the context] accidental capital carnival. Maxwell Technologies, with 1.43 billion yuan in orders in hand and the commercialization of its "thousand-card cluster," saw its market capitalization exceed 300 billion yuan on its debut day, setting multiple records. Biren Technology, as the "first domestic GPU stock listed in Hong Kong," received support from 23 cornerstone investors. Iluvatar CoreX, as the first company to achieve mass production of domestic 7nm training and inference general-purpose GPUs, listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange with performance covering more than 20 industries.

However, beneath the glory lie concerns: Iluvatar CoreX has accumulated losses exceeding 2.8 billion yuan over three and a half years, while Biren Technology has suffered losses exceeding 6.3 billion yuan during the same period, revealing the "bleeding charge" nature of this high-investment, high-risk industry as it races to seize the window of opportunity.

This is an industrial race concerning the future of intelligence: on one side, international giants are erecting technical barriers at a pace akin to "Huang's Law," while on the other, Chinese domestic forces are collectively breaking through with the dual support of capital and policies. To understand the underlying logic of this competition, we must trace the transformation of GPUs from gaming accessories to the core of computing power.

01

Defining the Core: The Transformation from Graphics Assistant to Computing Power Engine

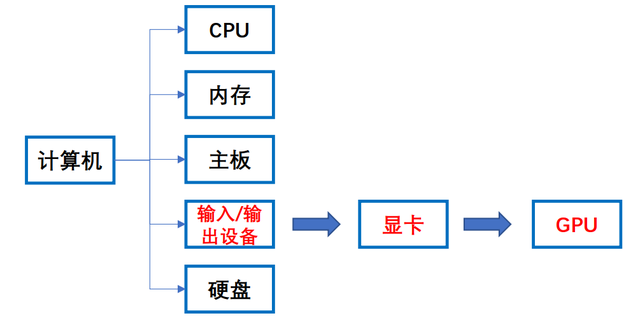

Before delving into this global computing power revolution, let's clarify a core concept—GPUs. GPU stands for Graphics Processing Unit. We often hear about CPUs (Central Processing Units), which differ from GPUs in architectural design: CPUs typically have a few powerful cores, excelling at handling complex general-purpose serial tasks, akin to a middle school student capable of solving advanced mathematics problems. In contrast, GPUs integrate thousands of relatively simple cores, specifically designed for processing massive amounts of homogeneous parallel tasks, much like hundreds of elementary school students collaborating to complete tens of thousands of addition and subtraction problems.

Figure: The position of GPUs in computers, compiled from publicly available data.

If CPUs are the "brains" of computers, responsible for decision-making and control, then GPUs are the "muscles" specialized in "large-scale repetitive labor." Their inherent parallel computing nature makes them far more efficient than CPUs in graphics rendering and high-performance matrix operations (the core of artificial intelligence).

With the advent of the 5G and artificial intelligence eras, AI computing such as machine learning in data centers now accounts for one-fourth to one-third of total computing volume. The burden of big data processing is shifting from CPUs to more powerful GPUs. GPU applications have long surpassed traditional personal computer graphics displays, with forms divided into discrete and integrated based on access methods; their domain has expanded to multiple scenarios including mobile devices, data center servers, and personal computers. Especially amid the AI and cloud computing waves, GPUs have become the core engines for data processing by leveraging their inherent parallel computing advantages, opening up an unprecedented growth market. Although more specialized computing chips like FPGAs and ASICs are also emerging in specific fields, the industry consensus is that GPUs remain the undisputed leader and dominant architecture in the current AI computing landscape due to their exceptional versatility, mature software ecosystem (especially NVIDIA's CUDA), and powerful comprehensive computing performance.

This positioning is the logical starting point for understanding its trillion-dollar industrial value.

02

The Origin of GPUs: An Entrepreneurial History from Gaming Graphics Cards to the Foundation of AI

The rise of the GPU industry is a typical Silicon Valley tech entrepreneurship epic, and its protagonist is undoubtedly NVIDIA. The story traces back to 1989 when several engineers jointly sketched out a blueprint for a new graphics accelerator. In 1993, NVIDIA was officially established, embarking on a rocky entrepreneurial journey. By 1995, the company faced the dilemma of having designed chips but lacking funds for factory construction. Founder Jensen Huang wrote to TSMC founder Morris Chang for help and successfully secured support.

This collaboration is seen by Huang himself as a pivotal turning point: "If I had built my own factory to produce GPU chips back then, I might now be a comfortable CEO of a company worth tens of millions of dollars." TSMC's foundry model allowed NVIDIA to operate with light assets, focusing on design and innovation, thus rapidly iterating products and capturing the market.

In 1999, NVIDIA made two industry-defining moves: one was to completely transition and focus on graphics chipsets, and the other was to introduce the revolutionary concept of "GPU" globally (though for quite some time after the concept's introduction, GPUs were still only used for graphics processing, far from the current widespread acclaim). That same year, the company went public on NASDAQ with a market capitalization of $626 million, initiating a legendary tale of over two decades of rapid growth.

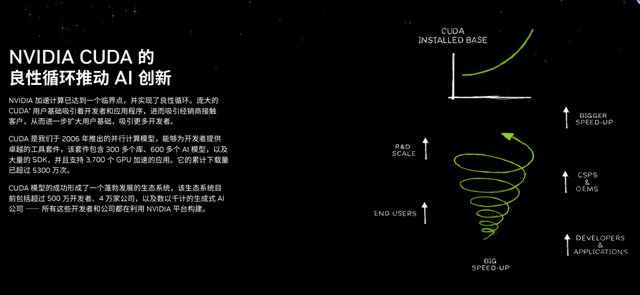

However, hardware performance leadership was not its ultimate weapon in building moats. The true "stroke of genius" came in 2006 when NVIDIA, while launching a new generation of GPUs, released the groundbreaking CUDA computing platform. CUDA, or Compute Unified Device Architecture, is essentially a set of software tools that enable developers to harness the powerful computing power of GPUs for general-purpose computing (GPGPU) with unprecedented ease, laying the groundwork for the subsequent explosion of deep learning.

Initially, the commercial value of CUDA was not immediately recognized by the market. But NVIDIA demonstrated remarkable strategic patience and foresight: it opened up and established R&D centers for free to universities and research institutes worldwide; supported startups in using it with funding; continuously open-sourced core software libraries; and even ensured that low-cost consumer-grade gaming graphics cards supported CUDA, lowering the development barrier to the thousand-yuan level.

After more than a decade of continuous irrigation without short-term returns, CUDA gradually evolved from a development tool into the de facto standard in high-end computing and graphics fields, constructing a profound ecological barrier comparable to an operating system. Even if competitors' GPU hardware performance parameters are similar, their popularity in the AI development community varies greatly, with the core difference lying in the development efficiency and computing performance enhancement brought by CUDA.

Figure: Description of CUDA, from NVIDIA's official website

It wasn't until around 2014 that NVIDIA perfectly integrated CUDA with AI computing, and NVIDIA's true takeoff began. Today, CUDA connects millions of developers worldwide, making NVIDIA GPUs the de facto "computing currency" in the AI era, with moats so deep they cannot be measured solely by transistor count or floating-point performance. This also explains why it is difficult for domestic GPU companies to achieve rapid overtaking.

03

Technical Competition: HBM, Architectural Iteration, and Performance Arms Race

The GPU industry's advancement at a pace akin to "Huang's Law" (display chip performance doubling every six months, AI computing power achieving a thousandfold increase in eight years) is driven by continuous technological innovation and a white-hot performance arms race. The author has comb, sort out, organize, arrange, streamline [Note: ' comb, sort out, organize, arrange, streamline ' is translated as 'compiled' to fit the context of organizing information] compiled that current technical competitions mainly focus on three key dimensions:

1. The Evolution of Storage Technology

The explosive growth of computing power requires not only a powerful "engine" (GPU core) but also a "high-speed grain path" capable of feeding the engine with data in real-time. Since 2017, NVIDIA has pioneered the use of HBM (High Bandwidth Memory) technology in high-end AI GPUs (such as A100, H100).

This is fundamentally different from traditional GDDR (Graphics Double Data Rate) memory: GDDR, as a traditional memory technology, offers balanced performance and cost, suitable for a wide range of graphics applications, while HBM focuses more on providing high-performance, high-bandwidth, and more energy-efficient solutions, suitable for fields with higher requirements for data transmission speed and energy efficiency. Structurally, GDDR is a traditional graphics memory, usually existing as a single chip, with a relatively flat design, and memory chips connected in parallel to the graphics processing unit (GPU). HBM, through cutting-edge packaging processes like 3D stacking and Through-Silicon Vias (TSVs), vertically stacks multiple layers of DRAM chips like building a skyscraper and tightly integrates them with the GPU logic chip through a silicon interposer. This design brings revolutionary advantages: HBM possesses several times the bandwidth of GDDR and lower power consumption, but at the cost of extremely complex structure and high cost.

Figure: H200, NVIDIA's official website

Take NVIDIA's H200 GPU released at the end of 2023 as an example; it is the first to carry, mount, equip, deploy [Note: ' carry, mount, equip, deploy ' is translated as 'equipped with' to fit the context] be equipped with HBM3e, boasting a memory bandwidth of up to 4.8TB/second. When used for inference on a 70 billion parameter large model, its speed is 1.9 times that of the previous generation H100, while energy consumption is halved. This clearly indicates that breaking through the "memory wall" is a matter of life and death for the continuous evolution of computing power.

2. Rapid Generational Leaps in Architectural Platforms

In the GPU industry, many companies view NVIDIA as the ultimate goal, but in the author's view, a harsh reality is that this ultimate goal is not standing still waiting to be surpassed but is still charging forward, maintaining a ruthless pace of architectural upgrades about every two years. Its next-generation platform, "Rubin," is already on the agenda, planned for mass production in 2026. Rubin is no longer just a single GPU chip but a vast computing system integrating Rubin GPUs, Vera CPUs specifically designed for AI inference, next-generation NV Link switch chips, and high-speed network cards. Among them, the key indicators of Rubin GPUs present a cross-generational leap: FP4 inference performance is expected to reach 5 times that of the current Blackwell architecture. This competition has escalated from a single "chip duel" to a "system platform war," comparing full-stack optimization capabilities from chips to clusters.

3. Dual Challenges in Graphics and Computing

Although AI computing is currently the biggest trend, the technical barriers of graphics display functions are actually more formidable. In terms of hardware structure, a complete GPU needs to integrate hardware units specifically optimized for graphics, such as rasterization, texture mapping, and ray tracing, with complexity far exceeding that of AI chips focused on matrix calculations. Algorithmically, graphics processing involves computer graphics, requiring the fusion of multidisciplinary knowledge such as physical simulation and optical rendering, with extremely high algorithmic difficulty.

Therefore, "full-function GPUs" capable of simultaneously handling high-performance graphics rendering and general-purpose AI computing represent the crown jewel in the field of chip design. This is also why many domestic GPU manufacturers have made "full-function" their core strategic direction.

As international giants forge ahead at the technological frontier, defining computing power standards with each generation of products, a crucial question arises before the global industry: on this track defined by the giants, is there still an opportunity for latecomers? China's answer is quietly being written in the laboratories of Zhangjiang, Shanghai, amid the clangor of capital market gongs and behind financial statements accumulating billions in losses. From technological followership to ecological breakthroughs, the journey of domestic GPUs is far more arduous and spectacular than imagined. We will continue our analysis in the next installment.