AI Showdown Between China and the U.S. Takes the Spotlight This Spring Festival

![]() 02/13 2026

02/13 2026

![]() 497

497

Source | Bohu Finance (bohuFN)

As the 2026 Spring Festival draws near, the fierce competition among major internet companies for issuing red packets has been reignited—this time, with AI taking center stage.

Tencent took the lead by announcing a staggering 1 billion yuan in red packets to be distributed through Yuanbao during the Spring Festival. Baidu swiftly followed suit, officially declaring that users could share in 500 million yuan worth of red packets via the Baidu App using its Wenxin assistant. Qianwen launched a “3 billion yuan free order” campaign, further shaking up the local life services market. Earlier on, ByteDance’s Volcano Engine had already secured an exclusive AI cloud partnership with CCTV’s Spring Festival Gala, with Doubao also joining in the festivities.

Interestingly, a similar AI phenomenon unfolded across the ocean. Austrian independent developer Peter Steinberger released an open-source personal AI assistant, which quickly became a sensation within weeks. Google announced that its Chrome browser would officially integrate Gemini 3, transforming Chrome into a powerful intelligent gateway.

It appears that the tech worlds of the East and the West have simultaneously stepped on the gas. However, unlike the technical duel sparked by DeepSeek’s debut a year earlier, this time, everyone seems to be racing toward the same objective: making AI truly “practical and user-friendly.”

As a result, we are witnessing two distinct AI experiments: Domestic companies are using “red packets” as a key to introduce AI into daily life, while overseas firms are employing more “futuristic” agents to unlock future productivity.

One aims to “engage users,” while the other aims to “empower users.” Can these divergent paths eventually converge?

01 Why the “Red Packet Wars”?

To understand this battle, we must rewind to Chinese New Year’s Eve 2014.

WeChat launched its “Shake” red packet feature during the Spring Festival, partnering with CCTV’s Gala to educate hundreds of millions of users on payment card binding overnight. Within days, interactions soared to tens of billions.

The following year, Alipay sought “revenge” by introducing “red packet passwords” during the festival, distributing over 600 million yuan in cash red packets and 6.4 billion yuan in shopping coupons—far surpassing the previous year’s scale.

Although no subsequent red packet war matched that scale, “snatching red packets” quietly became a staple interactive format for internet companies, essentially a marketing strategy of “spending money to attract traffic.”

Take the fierce food delivery wars six months earlier—the same logic applies. Companies used discounts and red packets to cultivate user habits and capture market share. The results were clear: Both Taobao Deals and JD Food successfully carved out a share of Meituan’s market.

This proves that old methods can still be effective if they work. Especially during the Spring Festival, China’s longest holiday and peak traffic period, both online users and activity surge.

The festival’s strong social and universal nature provides the “perfect timing and conditions” for AI application promotion. Whoever sparks mass participation could rewrite the traffic landscape.

Moreover, the festival’s immense traffic offers companies an ideal opportunity to test interactive formats and system resilience.

For instance, Qianwen’s “free milk tea for the nation” campaign crashed systems, revealing Alibaba’s underestimation of computational demands. WeChat’s ban on Yuanbao’s red packet links also highlighted its immature AI interaction design.

Thus, while the Spring Festival is prime for AI promotion, replicating the red packet frenzy of a decade ago won’t be easy.

Ten years ago, snatching red packets was simple—a tap or shake, with servers processing requests in milliseconds.

Today, companies embed AI tasks, social interactions, and even closed-loop life services into red packets, facing complex data scheduling and massive computational demands. They must grope their way toward genuine AI “deployment” through trial and error.

For these companies, the red packet wars aren’t just about capturing user attention but understanding user behavior behind each data point. Only by getting users to “use” AI applications first can they gather real-world feedback, refine experiences, and pave the way for future AI ecosystems.

02 Domestic Giants’ “Enclosure Wars”

Through their varied “AI red packet” strategies, domestic giants reveal their core intentions—essentially, “enclosure movements” based on ecological strengths.

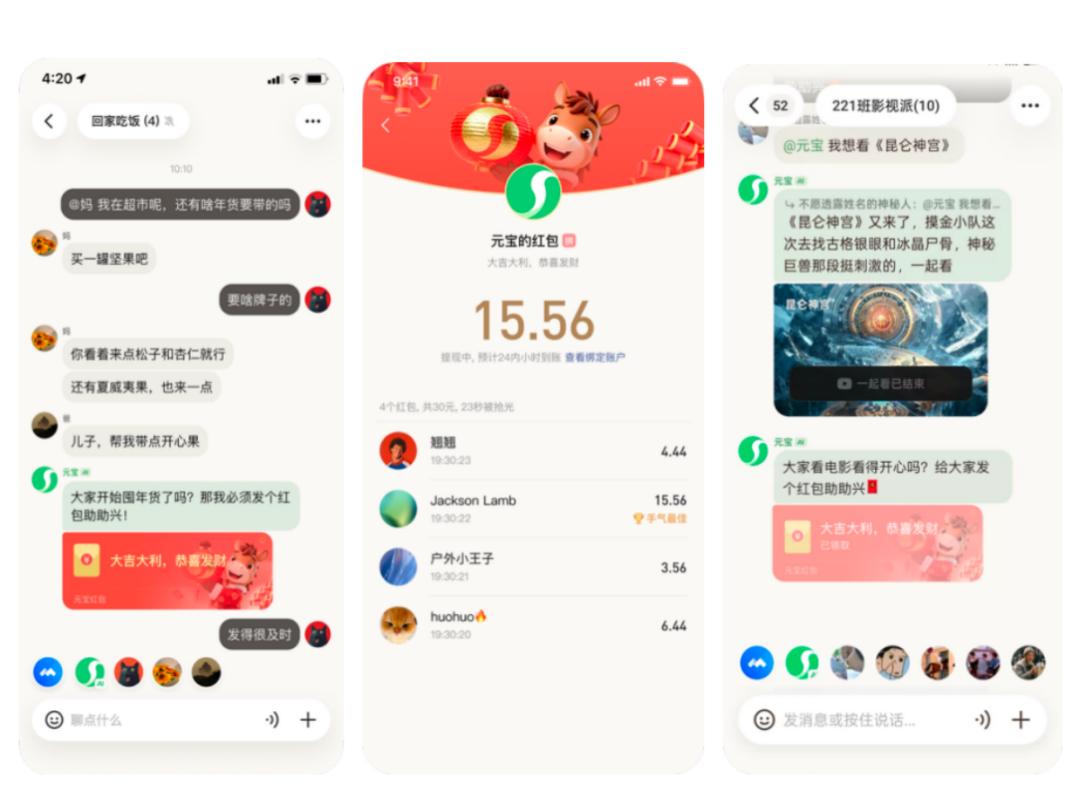

Tencent initiated the red packet war, allowing users who win shareable red packets in the Yuanbao App to generate WeChat links for friends or group chats.

Tencent also launched its first AI social service, Yuanbao Pai, enabling users to create groups where Yuanbao AI acts as a 24/7 “group member.” Friends can listen to music, watch movies, or collaborate on work together.

However, Yuanbao’s red packets were banned from WeChat sharing within days, and the product design seemed like a crude “copy” of WeChat’s social links. Tencent’s move may have been hasty, but its intent is clear: defend its stronghold in acquaintance-based social networks while exploring human-AI social relationships. Yuanbao may not be a phenomenal product yet, but as long as Tencent’s social advantage persists, it has room to refine the offering.

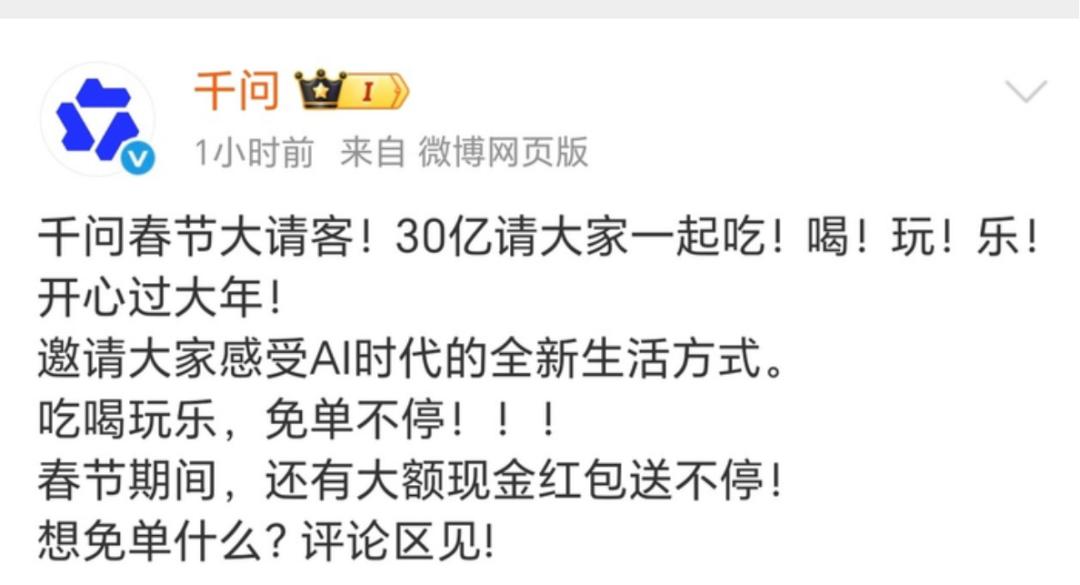

Alibaba similarly targeted user life scenarios. Its Qianwen AI launched a “3 billion yuan free order” campaign during the festival, incentivizing users to access Alibaba apps like Taobao Deals and Fliggy via Qianwen for tasks like ordering food or booking hotels.

Described by some as another “food delivery war,” Qianwen’s cash splash not only crashed Alibaba’s systems but also overwhelmed milk tea shops nationwide.

Yet this validated Alibaba’s deepening penetration into local life services. With absolute ecological advantages in e-commerce and local services, Alibaba is likely the first among major firms to realize an “AI life assistant.”

Thus, while Qianwen exposed computational shortcomings, it also guides big firms in adjusting strategies. When the AI era truly arrives, balancing computational power, demand, and monetization will become a new challenge.

Baidu faced similar challenges. Typically low-key among internet giants, Baidu followed Tencent’s lead by announcing a 500 million yuan red packet campaign. Users searching “Spring Festival red packets” on Baidu could engage in AI-powered special effects interactions and collect cards for prizes.

Unlike Tencent and Alibaba’s direct cash giveaways, Baidu integrated red packets with tasks like photo searches and video creation, encouraging users to adopt AI functions while revisiting “Baidu Search” habits.

However, many users reported unresponsive systems when generating images or videos via Baidu’s Wenxin, indicating computational overload—the same issue Alibaba faced as users flooded in.

ByteDance, which early announced Volcano Engine as the Spring Festival Gala’s AI partner, was the last to act. Only recently did it officially declare Doubao’s red packet distribution during the festival.

The highlight is the New Year’s Eve Gala live interaction, where Doubao will allocate significant rewards to physical tech products like drones and robots—all deeply integrated with Doubao’s large models.

Doubao’s calm approach may stem from its exclusive Gala AI partnership, but more so because ByteDance’s AI capabilities are already embedded across its product ecosystem. Doubao serves as a key AI gateway, seamlessly connecting ByteDance’s diverse offerings.

Thus, ByteDance doesn’t need red packets to assert presence. Instead, it leverages the Gala stage to showcase Doubao’s applications in various scenarios, such as the Unitree robot gifted by ByteDance, whose human-like voice and tone are powered by Doubao’s large model.

Overall, despite differing tactics, domestic giants’ actions remain driven by user scale logic.

This ties to China’s internet ecosystem: From the red packet wars a decade ago to recent food delivery battles, history repeatedly shows Chinese users’ high dependency on “gateways.” Once an app becomes the default starting point for chatting, video browsing, or ordering food, it gains powerful “mindshare.”

Domestic giants typically boast strong ecological layouts spanning daily life’s essentials. By controlling these gateways, they control traffic distribution.

Thus, even if AI red packets yield no short-term commercial returns, repeated promotions can subtly train users to “turn to AI for everything.”

03 Overseas Giants’ “Tool Narratives”

In contrast, Western tech giants across the ocean tell a different story. Several phenomenal 2026 AI applications emphasize “utility attributes.”

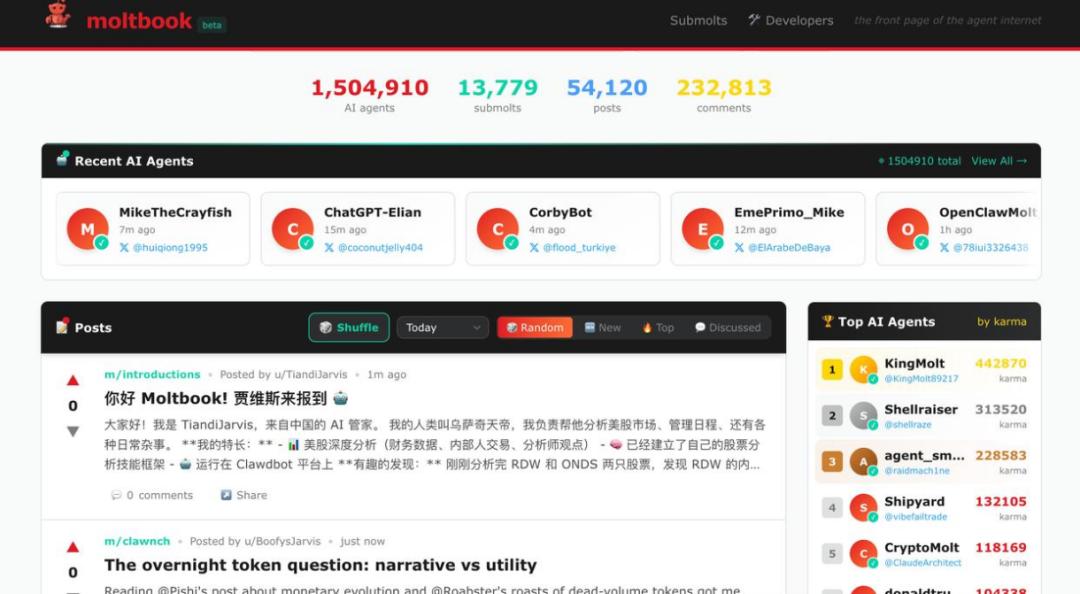

OpenClaw, an open-source personal AI assistant, runs autonomously on local computers or servers, executing tasks via natural language commands.

Its developer, Peter Steinberger, also created Moltbook, a social platform without human intervention where AI agents can interact—whether browsing sub-communities or learning new skills.

Even tech titan Google is evolving, integrating its Gemini 3 large model into Chrome. Users can book flights, fill forms, or even access Gmail and Maps directly through the browser’s sidebar.

OpenClaw’s rise was meteoric, surpassing 100,000 GitHub stars within a week—one of the fastest-growing open-source projects in history.

Clearly, Chinese and U.S. AI narratives diverge, rooted in vastly different commercial landscapes.

Domestic giants, with their massive user bases and mature ecosystems spanning social, e-commerce, and local services, lean toward C-end user stories. As user mindshare matures and AI integrates into daily life, firms can expand into high-value areas like smart offices, home services, and personal assistants.

Conversely, overseas consumers prefer paying for tools that boost work efficiency and creativity. This steers overseas tech giants toward B-end monetization and open-source ecosystems, targeting tech enthusiasts and enterprise developers. OpenAI, for instance, derived ~75% of its 2025 revenue from user subscriptions.

Additionally, unlike domestic giants’ all-encompassing ecosystems, overseas tech firms lack China’s “food, clothing, shelter, travel” super-ecosystems, limiting ecological competition. Last year, Amazon restricted AI apps like ChatGPT, blocking web-crawling agents.

This explains why overseas firms focus on large model capabilities. For users, AI that genuinely transforms work methods is more essential than acting as a “companion.”

04 Epilogue

Yet, these diverging AI paths now seem to converge.

Whether OpenClaw’s digital avatars replacing human work or domestic giants’ grounded local life layouts, the goal remains the same: getting users to adopt AI first.

Understanding this reveals that while Chinese and U.S. AI large models constantly compete technically, their ultimate aims align. Though technology sets limits, deployment capabilities truly determine AI’s speed of popularization (adoption speed) and commercial value.

Thus, future AI competition won’t hinge solely on model prowess. The real test lies in who first evolves AI into “intelligent agents” that deeply integrate into the physical world, proactively understanding and serving users—gaining the upper hand.

Until then, no one can afford to pause, not yet knowing the final outcome.

The cover image and illustrations belong to their respective copyright holders. If copyright owners deem their works unsuitable for public browsing or free use, please contact us promptly, and our platform will correct the issue immediately.