The Retreat of Early Investors from the Humanoid Robot Race: A Positive Turn for Innovation

![]() 04/03 2025

04/03 2025

![]() 659

659

Recently, the humanoid robot industry has ignited intense debates.

Zhu Xiaohu of GSR Ventures has issued a "retreat declaration," announcing the withdrawal from numerous humanoid robot projects, such as Xinghai Robotics. He bluntly remarked, "A machine costing 200,000 yuan can't even hold a cup of coffee steadily, and state-owned enterprises' purchases are mere vanity projects."

This "bubble theory" instantly sparked discussions: Zhang Ying of Matrix Partners responded on WeChat Moments, urging Zhu Xiaohu not to stir up trouble, while the CEO of Zhongqing Robotics sarcastically labeled him as someone who "only deserves fast-food investments." Xinghai Robotics, which was exited, countered with data on takeovers by Hillhouse Capital and Ant Group to refute the claims.

In my view, the primary discussion point in this incident should not be the feasibility of the race but rather another crucial question: What kind of investment institutions are most needed for this trillion-dollar humanoid robot industry?

-01-

First and foremost, I unequivocally oppose herd behavior among institutions. The venture capital community has suffered significantly from this phenomenon over the past decade. In the short term, some star projects benefit, being hoarded by institutions and receiving excessively high valuations.

However, in the long run, an influx of funds into a particular sector leads to an oversaturated market with too many star participants, resulting in a severe oversupply. Ultimately, this often results in a queue of unprofitable unicorns waiting for IPO, all starving for funds to sustain them.

Caption: The bubble in the industry caused by herd behavior among investors over the past decade.

These issues then shift to the secondary market: Should these unicorns be allowed to go public? If they are, there are too many companies with little differentiation for the market to absorb; if not, their capital chains may snap, affecting numerous investors waiting to exit. Failure to exit could trigger a capital winter in the primary market, thereby stifling technological innovation.

There's an industry joke: "If you don't let me go public, my company will go bankrupt." Such cases do exist objectively.

I am also opposed to herd behavior in the humanoid robot industry. During the 2025 Spring Festival Gala, Unitree Robotics gained popularity, and I was initially pleased. This company, founded in 2016, caught my attention when Pencil News organized the 'Unicorn Escort Plan,' during which I exchanged ideas with its founder, Wang Xingxing.

However, things took a turn for the worse. When almost the entire nation became aware of Unitree, investment institutions began to swarm in.

For instance, there was a rush to buy old shares, with some institutions offering a valuation premium of 12 billion yuan (a 50% premium over the C round of 8 billion yuan) to secure them. Some investors even said, 'As long as I can invest, everything else comes later.' During this period, intermediary institutions approached me to inquire about participating in discounted old shares.

Frankly, I disapprove of these actions. Equity investment earns profits from 'cutting-edge insights.' The premise of making money is discovering valuable companies early and investing in them. Now that the entire nation is aware of Unitree Robotics and the value of humanoid robots, and you're only acting now, isn't it too late?

Investment competition is akin to a queue game; those at the front get the best deals. If you're at the back, even behind the general public's awareness, can you still get the best? You might not even get the scraps.

In the long run, this type of investment behavior is detrimental to the market.

While it can temporarily alleviate the market's capital shortage, due to the herd behavior of funds, there is often no long-term vision, just fleeting enthusiasm. Once the industry cycle cools, their enthusiasm wanes, and they may consider exiting after 3-5 years, for example, by using methods like 'unlimited joint and several liability + repurchase' to make things difficult for companies, leaving long-term hidden dangers.

From this perspective, I appreciate Zhu Xiaohu's stance – because some of his remarks may benefit the industry. At the peak of the humanoid robot bubble, his words may make some herd behavior institutions sober up, thereby preventing the waste of significant funds.

-02-

As for the rest, you needn't take it too seriously: whether humanoid robots succeed or fail will ultimately depend on action, which can be discussed now.

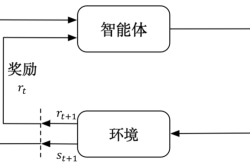

Personally, I am optimistic about the prospects of humanoid robots. The core reason is that in society, any commodity or service is designed to facilitate human behavior, such as cups, keyboards, and mice.

If robots are to maximize their value, the core principle is: 100% compatibility with humans. What humans can use, robots can also use, and everyone follows the same rules, becoming one species.

Of course, when will this point be reached? In 3 years, 5 years, 10 years, or 20 years. For investment institutions, this is a practical concern: they need to exit within 8-10 years. So, can robot companies allow them to exit safely?

I believe a safe exit must meet two conditions:

1. In the next 6-8 years, humanoid robots must have the potential for IPO.

2. Robot companies cannot have an oversupply or excessive homogenization.

Regarding the second point, it has been mentioned earlier that investment institutions should not flock in and invest in a batch of homogenized companies.

Especially in the humanoid robot industry, which is currently in the technology validation phase and will gradually move towards market introduction in the next 1-3 years, order capacity is limited and cannot support numerous humanoid robot companies.

Caption: Commercialization scenarios for humanoid robots

Based on my experience, when there are 3-5 leading competitors in the same niche, it becomes challenging for newcomers to enter. If new institutions still wish to participate, they should invest in these established players rather than cultivating new ones, which is healthier for the industry.

Otherwise, it will easily lead to herd behavior.

For example, in the past 1-2 years, a dozen autonomous driving unicorns went public, with little differentiation and insufficient market capacity, leading to severe losses for each. Most are in a precarious state, fearing they won't survive if they don't list within two years. Personally, I am reluctant to see such a scenario repeat, wasting vast funds and resources.

As for the first question: in the next 6-8 years, will there be a wave of humanoid robot companies going public? I believe there is a chance.

First, supply chain companies may take the lead in profitability. For example, a precision electronics company (net profit up 796.99% year-on-year) and a spring manufacturer (net profit expected to increase by 214.51%) have already seen their performance soar.

Secondly, among robot manufacturers, with the avoidance of herd behavior, some companies can pioneer breakthroughs in industries, scientific research, and education.

For instance, Tesla's Optimus Gen2 has received over 5,000 orders from automakers, priced at $200,000 each, primarily used in factory automation production lines. Unitree Robotics' H1 robot, with 60% of its orders coming from industrial scenarios, delivered over 1,200 units in Q1 2025.

From a market cycle perspective, it will take at least 5-10 years for humanoid robots to achieve large-scale commercialization. However, in the current market introduction phase, some orders can already enable leading companies to thrive.

But the premise is: there cannot be herd behavior; otherwise, no one will survive. Therefore, such industry discussions on humanoid robots are, in my opinion, beneficial and necessary.

The content of this article is for reference only and does not constitute any investment advice.