Let's seriously discuss humanity's fate in the era of 'AI Hegemony'

![]() 08/29 2024

08/29 2024

![]() 429

429

I believe most readers of our group have received higher education, including many graduates from prestigious universities. Let's recall, what was your dream job during your student days? And what job did you actually end up with after graduation? There are bound to be many answers, but they all share a common theme—most likely belonging to the so-called 'professional white-collar positions'.

When I was studying over a decade ago, the internet industry was not yet prevalent. Business school students aspired most to careers in finance, followed by management consulting, and then as 'management trainees' in large foreign or state-owned enterprises. Joining the Big Four accounting firms for auditing or tax consulting was also a popular path, as they recruited heavily and provided residency permits. The booming real estate industry at the time also absorbed graduates from top universities, but most were not involved in selling or designing houses; rather, they worked in strategy, investment, business analysis, and corporate management.

What do the above-mentioned professions have in common? They all belong to the 'professional services' sector or professional service positions within comprehensive enterprises. The scope of 'Professional Service' can be broad or narrow, encompassing even enterprise software and consumer internet industries in a broad sense. These industries share the following characteristics:

They neither belong to the primary industry (agriculture, mining) nor the secondary industry (manufacturing); they can only belong to the tertiary industry (services). The term 'professional' encompasses both the professionalism of the service itself and that of the practitioners: a bachelor's degree is the basic threshold, most practitioners hold a master's degree, and many are members of professional organizations. Professional service organizations are 'high-intelligence, labor-intensive' enterprises, with their employees' intelligence being their greatest asset. While capital and equipment are important for some organizations, human resources remain paramount. The services they provide are relatively expensive, with high unit prices. After deducting all non-human costs and corporate profits, they can still offer substantial salaries to employees, although employees may still feel dissatisfied.

In developed countries, doctors and lawyers symbolize professional services, and even those without higher education know they are respected, lucrative professions. In the film 'Election 2: Harmony is Precious' directed by Johnnie To, the protagonist played by Louis Koo, as the boss of a notorious Hong Kong gang, dreams of his unborn son becoming a doctor or lawyer. When outsiders suggest he should pass on his gang leadership to his descendants, he is deeply offended, muttering, 'No, my son will be a doctor, my son will be a lawyer…' In fact, whether in Hong Kong, the United States, Western Europe, or anywhere deeply influenced by Western culture, who wouldn't want their son to become a doctor or lawyer? Apart from these, working on Wall Street in finance is another high-paying and respected profession, though their work is too remote from the average person to be well-understood by non-professionals, lacking the immediacy and accessibility of doctors and lawyers.

What are the thresholds for professional service organizations? What are the resource endowments required for individuals to pursue this field? These two questions are essentially the same. Most professional service industries have licensing restrictions, such as for law firms and individual lawyers. The same applies to doctors, accountants, and financial practitioners. Licensing systems facilitate supervision and accountability and ensure practitioners possess basic competencies. In developed countries, except for medical services, licensing regulations in most professional services are relatively loose, with industry competition primarily governed by market mechanisms. Licensing is merely a baseline requirement.

Apart from licensing and a certain level of capital, the most crucial threshold is 'professional knowledge.' Professional knowledge does not equate to creativity and can even be completely unrelated. In the classic scene from 'The Shawshank Redemption,' when the prison guards on the roof of Shawshank State Penitentiary complain about heavy tax burdens, the protagonist Andy immediately comes up with a legal tax reduction plan, winning their gratitude and several crates of cold beer. Andy was a banker before his imprisonment, not a tax consultant, but he was familiar with tax laws. The question is, did he solve their problem through creativity? Rather, it was through memorization and pure experience. In a nutshell, it was 'routine work.'

According to Han Yu's 'On Teaching,' 'People learn at different times and specialize in different skills.' In professional services, the value of knowledge first lies in creating an information gap—what I know and you don't. Second, it forms proficiency through repetition, leading to so-called 'conditioned reflexes.' Over time, practitioners gradually realize that knowledge is not the most critical threshold; instead, the relationships and personal brands formed over a long career are. Ultimately, any service industry involves interacting with people, from waiters serving coffee in roadside cafes to senior lawyers issuing orders from high-rise offices. However, only those at the pinnacle of the pyramid have the privilege and conditions to establish intricate networks. The vast majority of workers at the middle and lower levels still rely on 'knowledge' to support their families.

Undoubtedly, the prevalence of AIGC will severely impact the entire professional services sector, particularly mid- and low-level workers. Even before contemporary deep learning technologies emerged, IBM attempted to replace some doctors with its Watson AI solution. Due to a shortage of doctors and an overburdened healthcare system in developed countries like the US and UK, many doctors actually welcomed this substitution, though IBM failed to deliver. Now, with some training, ChatGPT can provide initial financial, tax, legal, and even medical advice to users, with the sole drawback being its inability to take responsibility for its recommendations. As the legal framework surrounding AI matures and vertical applications become more widespread, AIGC could genuinely threaten many people's livelihoods.

During my over a decade in the financial industry, I witnessed firsthand how information technology impacted this ancient and arrogant sector. Among the most profitable and well-compensated areas in finance are capital market-related businesses (often collectively referred to as 'investment banking,' although investment banking is just a small part of it), including investment banking, sales and trading, research, asset management, wealth management, and more. From the late 20th century to the early 21st century, they gradually felt the pressure brought about by information technology:

The electronic trading of securities began in the 1970s. Today, offline securities trading is almost non-existent, and the proportion of electronic trading requiring manual intervention is decreasing. While capital market trading volumes soar, financial institutions charge lower commission rates and spreads, offering fewer differentiated services.

Before the 2000s, securities research was a lucrative business. However, due to tightening regulations and internet-driven information transparency, research operations now generate buzz but little profit. In terms of timeliness and depth, the influence of financial institutions' research departments has lagged behind internet-based financial media.

In the narrow sense, investment banking, encompassing securities issuance and mergers and acquisitions, remains profitable but not as much as before. Investors' valuation methods for companies have become increasingly diversified, diminishing financial institutions' 'pricing power'—in August 2004, Google's IPO first adopted an 'online auction' pricing mechanism. Financial institutions receive lower commission rates from investment banking transactions.

Asset management and wealth management, known as 'buy-side' businesses, have been the focus of financial institutions in recent years due to their stable revenue streams. However, these businesses have also been profoundly transformed by the internet. A significant portion of 'fintech' companies in Europe and North America are deeply integrated with information technology in asset and wealth management.

The prevalence of AIGC could be the final straw that breaks the camel's back. Taking China's rapidly developing wealth management sector, including private banking, trusts, and family offices, clients prioritize financial knowledge and advice, followed by access to efficient investment tools. AIGC can efficiently meet the first need. For 'entry-level' clients with modest assets, chatbots fine-tuned based on large AI models suffice and may even save costs. Given that finance is traditionally the most technologically advanced professional service sector, if it is impacted in this manner, what will happen to other professional services?

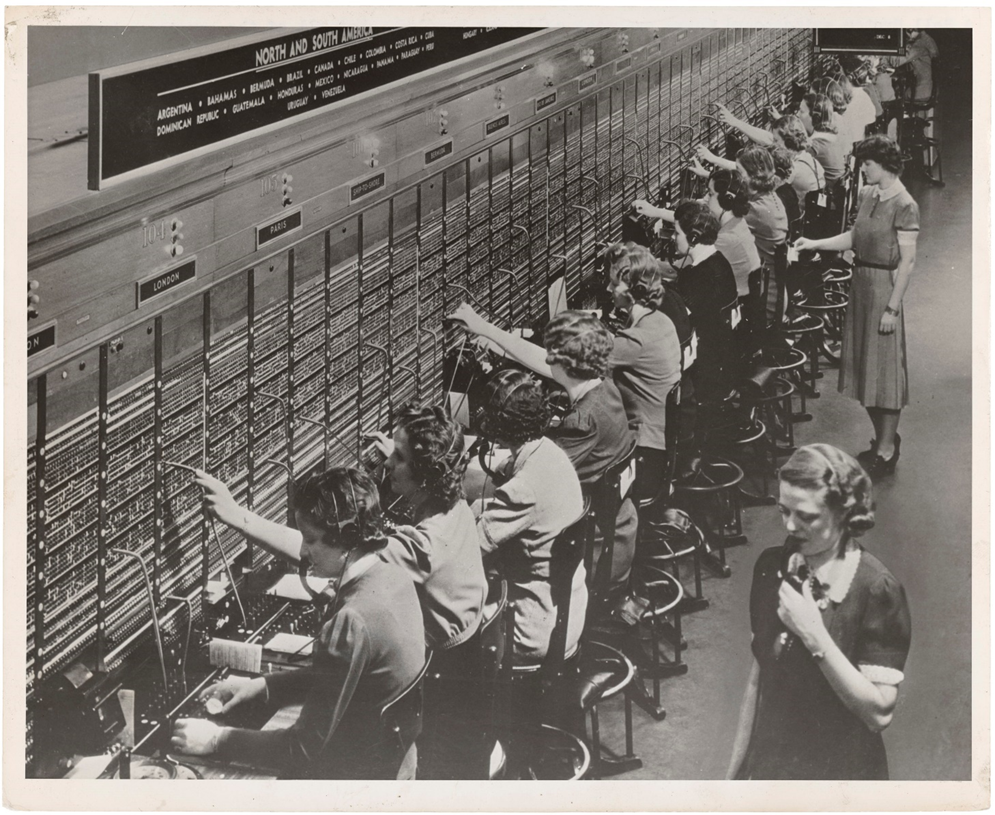

Don't misunderstand; the finance industry won't disappear, nor will accounting, taxation, law, or healthcare services. As long as demand exists, supply must be created, the question being 'by whom'—humans or AI? Historically, countless industries have seen humans replaced by machines they themselves created. Early telephone systems were labor-intensive, with dozens or even hundreds of operators sitting in front of telephone switches, answering user requests through headsets and connecting calls manually. This persisted until the end of World War II! Another example is elevator operators, who were once essential due to manually operated elevators. With automation, their primary role shifted to maintaining order and safety before gradually disappearing. Today, elevator operators are only found in hospitals or select secure locations.

While telephone operators and elevator operators may seem low-tech, they were undoubtedly 'professional service positions' when they emerged. Early telephone switches and elevators were sophisticated electrical devices requiring training to operate. Their high costs meant companies entrusted them only to trusted employees, inadvertently raising entry barriers. In the 20th century, most telephone operators were women, offering good job opportunities for them and, to some extent, promoting women's emancipation and gender equality. It was information technology that ultimately eliminated their jobs—'program-controlled telephone switches' no longer required operators, where 'program-controlled' means 'computer program-controlled.' Elevator operators faced a similar fate, as today's elevators are essentially 'program-controlled.'

In contemporary professional services, automated trading programs have replaced a significant portion of securities traders; online and mobile banking have supplanted many bank tellers; content recommendation algorithms have taken over from many professional editors; and financial software has substituted for a considerable number of financial workers. However, the term 'replacement' is too simplistic, as traditional computer programs still require human operation and have limited natural language understanding capabilities. Thus, they assist professional white-collar workers more than they replace them. Those who survive into the computer age occupy positions less vulnerable to complete replacement.

However, large AI models differ from previous computer programs: they comprehend natural language, execute 'generative' tasks, access and utilize vast human knowledge; now, they even possess multi-modal and long-text comprehension abilities. While they can assist professional white-collar workers, they are fully capable of taking center stage, even concurrently performing supporting and lead roles. Even the information technology industry itself feels the pressure of AIGC, as computer programmers, who once shook up other traditional industries, now face an earthquake from AIGC. We're still in the early stages of AIGC development, mere years since the advent of Transformer technology in 2017. Five or ten years from now, significantly enhanced AIGC tools will undoubtedly excel at taking center stage, inevitably leading to a reshuffle among tens of thousands of professional white-collar workers.

What does this imply? Mass unemployment, another industry transitioning from sunrise to sunset? A drastic decrease in the labor force required by society? Or perhaps humanity no longer needs to work? While these possibilities cannot be ignored, we must consider others: as the Western adage goes, 'When God closes a door, he opens a window.' Could structural unemployment in white-collar jobs due to AIGC merely spark another industrial revolution, with those who lose their jobs eventually finding new ones in other industries?

If we must identify an emerging industry that absorbs employment, or one that is 'safer for workers,' I immediately think of those that inspire, move, and share joys and sorrows with people. We are humans, complex beings with wisdom and emotions, preferring to interact with our kind. In a April 2024 speech at Stanford University, Sam Altman mentioned that humans still prefer humans, even when AI outperforms them in chess. He cited counterexamples, like teenagers preferring to discuss their mental health with AI rather than psychologists, which is understandable given the privacy concerns involved.

I recall when 'virtual idols' (Vtubers) emerged, some investors were thrilled, believing they would revolutionize the entertainment industry and beyond. The entertainment sector heavily relies on stars, with many film and television companies essentially working for them; the same applies to the live streaming industry, where top streamers can overshadow guilds or even platforms. Replacing humans with virtual idols seemed highly beneficial for capital. Many companies pitched this narrative to investors, resonating widely.

What was the outcome? Today, virtual idols have indeed made significant progress, with some top idols earning substantial sums—yet they're far from replacing humans. In live entertainment, gaming, and e-commerce streaming, the most profitable and influential streamers are still human. The same holds in the entertainment industry, where 'virtual singers' like Hatsune Miku and Luo Tianyi haven't brought about any fundamental changes. Fans of successful virtual idols are often eager to uncover their 'real person,' the voice and motion provider behind the avatar. They may seem to adore a digital creation but ultimately cherish the human soul beneath it. If the capital behind a virtual idol dares to replace the 'real person,' they risk losing a significant portion of their fan base.

What is humanity's uniqueness or irreplaceability? Shakespeare extolled humanity in 'Hamlet': 'What a piece of work is a man! How noble in reason! How infinite in faculty! In form and moving how express and admirable! In action how like an angel! In apprehension how like a god! The beauty of the world! The paragon of animals!' That was in the 16th century, before the Industrial Revolution, when humanity hadn't yet unleashed its transformative technological power. Yet, the civilization they created was already remarkable. In the centuries since, humanity has achieved monumental cultural and technological feats while also inflicting devastating disasters. Discussions about humanity's replaceability as a whole have intensified after two world wars. Will the civilized world humanity has crafted ultimately lead to their own obsolescence? This question is both pragmatic and philosophical. We know that in nature's evolution, no species is eternal.

Is AI the substitute created by humans to replace themselves? Not just a certain individual or group, but the vast majority, or even everyone? To address this question, I would like to quote from William Falkner's speech upon receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1950, which is one of my favorites:

"I refuse to accept the end of man. One could argue that man is immortal, simply because he will endure: that when the last ding-dong of doom has clanged and faded from the last worthless rock hanging tideless in the universe, even then there will still be one more sound: that of his puny inexhaustible voice, still talking. I refuse to accept this. I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet's, the writer's, duty is to write about these things. It is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past. The poet's voice need not merely be the record of man, it can be one of the props, the pillars to help him endure and prevail." When Faulkner was alive, the information technology revolution was still in its infancy. Back then, doubts about humanity's future stemmed primarily from fears of nuclear weapons and the next world war. If Faulkner were alive today, the AIGC wave would not have altered his perspective on human destiny. Humans possess souls, courage, honor, hope, pride, compassion, mercy, and the spirit of sacrifice. These virtues not only help humans survive but also define their glory. Although there are scoundrels among us, not everyone possesses these virtues, but humanity as a whole is immortal. I believe this is the fundamental reason why humans prefer to interact with other humans. When we are with our own kind, we know that they have feelings and thoughts, hunger for food when hungry, desire sleep when tired, long for love, and feel pain when hurt. When we express emotions towards them, they are likely to reciprocate. In this cold and empty universe, on a planet primarily composed of rocks and lava, we warm each other, confide in and understand each other, creating a small and cozy home. What we create based on silicon chips and metal wires is remarkable; it can accomplish tasks in seconds that might take us days and still not be guaranteed. Yet, they remain cold. The warmth they seem to possess is merely an imitation of humans, taught to them step by step. However, humans often do not understand why they love, why they have a sense of honor, why they are compassionate, or why they sacrifice for others. As individuals, humans often engage in unprofitable foolishness: "I insist," "I'll go even if a million people stand in my way," "I won't budge an inch in the face of truth." Humans have never truly liked the world they inhabit. Some choose to escape it, some to transform it, and others to transcend it. Transformation and transcendence are far more challenging than escape or simple adaptation. Why do humans make such thankless choices? Is it biological instinct, a subconscious formed over long years, or, as Faulkner described, do humans truly have souls? If a teacher does not understand the origins of their skills, how can they teach them to students? AIGC is that student. In the classic science fiction film "Terminator 2," the Terminator played by Arnold Schwarzenegger is a humanoid robot equipped with a neural net CPU (the screenwriters of the time could not have foreseen that the computational foundation of modern neural networks would be GPUs rather than CPUs). The Terminator arrives to save the young John Connor. It excels in combat but cannot comprehend human emotions. When John cries, the Terminator asks, "What's wrong with your eyes?" At the end of the film, to sever the enemy's tracking, the Terminator sacrifices itself by plunging into molten steel. John cries again, and this time, the Terminator understands. As it wipes away John's tears, it says, "Now I know why you cry, but that is something I can never do." Will AI ever learn to cry? Even if that day comes, it will be far in the future. Until then, we should cherish all the strengths and weaknesses that make us human. By recognizing our uniqueness, we can always find a new path under the so-called "AI hegemony"—admittedly, an overly optimistic view. But as a common saying in capital markets goes, "Pessimists are often right, but optimists win in the end." Even without solid reasons, we must remain optimistic about humanity's future; besides, we do have solid reasons. This article is excerpted from Chapter 6 of the new book "Giant Waves: The Epic and Reality of Generative AI" by the Internet Pirate Group, with minor revisions and omissions.