Trillion-Yuan Food Delivery War: Financial Reports of the Three Industry Leaders Released, Showing a Tenfold Difference in Loss Ratios

![]() 12/02 2025

12/02 2025

![]() 426

426

The half-year trillion-yuan food delivery battle has recently submitted its “mid-year performance report,” revealing results so grim that one wonders: Was this battle even worth waging?

Recently, Meituan, JD.com, and Alibaba have sequentially released their financial statements. The top performers and the laggards are clearly distinguishable.

JD.com reported losses of 30 billion yuan over two quarters, while Alibaba incurred a single-quarter loss of approximately 36-40 billion yuan. Meituan’s core local business experienced a loss of 14.1 billion yuan.

In such a brief period, within an industry with a mere 3% net profit margin, nearly 100 billion yuan was expended. This marks the fiercest cash-burning war in the internet sector over the past three years.

By connecting the dots, a conclusion emerges: The food delivery war is not impossible to win, but it cannot be fought recklessly. Reckless combat leads to pure losses—the fiercer the battle, the faster the losses accumulate.

Why? The financial statements offer three practical answers:

The food delivery war is not about burning money but about efficiency. This is evident from each company’s “loss ratio.”

The food delivery industry is inherently low-margin and cannot withstand prolonged subsidy wars. While short-term subsidies may delight users, long-term reliance will only lead to ruin.

Food delivery is not e-commerce; their operational logics are entirely different. The idea of using food delivery to drive e-commerce growth may be a miscalculation. Thus, from its inception, this war may not be sustainable.

Next, this article will dissect the trillion-yuan battle step by step, examining efficiency competition, subsidy traps, and sectoral logic to reveal who is burning money to defend market share and who is learning costly lessons.

- 01 -

Times have changed. This is no longer the bygone era of internet competition, where having more money or offering bigger subsidies guaranteed market share. That logic is obsolete and even more irrelevant in today’s food delivery industry.

What truly matters in the food delivery war? It’s efficiency, loss ratio, and who can secure a larger market share with less money.

What is a loss ratio? Imagine an ancient battle where you and your opponent both aim to capture a city. The enemy needs 30,000 troops, while you only need 10,000. This ratio is the loss ratio.

In this food delivery war, “losses” represent the resources you deploy, while “revenue” represents the city you aim to capture. Spending fewer losses to generate more revenue means higher operational efficiency and a lower loss ratio.

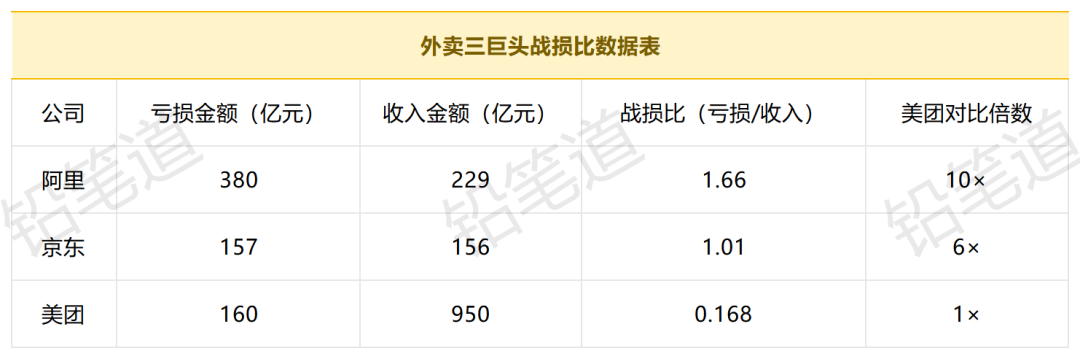

Through the performance reports, we can calculate each company’s loss ratio.

Roughly estimating from the loss ratios, Meituan ranks first, JD.com second, and Alibaba third.

First, let’s compare Alibaba vs. Meituan.

In the third quarter, Alibaba burned 38 billion yuan in instant retail, generating 22.9 billion yuan in revenue.

How was the 38 billion yuan figure calculated? In the third quarter of last year, Alibaba’s China e-commerce group reported an adjusted profit of 44.3 billion yuan. Assuming a 10% revenue growth rate, its theoretical profit should have been 48.7 billion yuan, but the actual profit was only 10.5 billion yuan—a shortfall of 38.2 billion yuan, roughly Alibaba’s actual loss (instant retail).

As for Meituan, its latest quarterly results show: It incurred 16 billion yuan in losses (including local commerce and new businesses) to generate 95 billion yuan in revenue.

Converting this to a loss ratio: For every 1 yuan of revenue, Alibaba lost 1.66 yuan, while Meituan lost only 0.168 yuan. Conclusion: Alibaba’s loss ratio is ten times that of Meituan.

Now, let’s compare JD.com vs. Meituan.

Since JD.com did not disclose precise data, we can only make a rough comparison. In the third quarter, JD.com’s “new businesses” (food delivery, JX self-operated, overseas business) incurred losses of approximately 15.7 billion yuan, generating about 15.6 billion yuan in revenue.

Converting this to a loss ratio: For every 1 yuan of revenue, JD.com lost roughly 1 yuan—about six times Meituan’s loss ratio.

It’s important to note: Since JD.com’s food delivery is bundled with JX and overseas business, this is only a rough estimate.

Even so, it’s clear: Meituan achieved with 1 yuan what its competitors achieved with 6-10 yuan.

The vast gap in loss ratios proves one thing:

The food delivery war cannot be fought recklessly. It’s not about subsidies but about systemic efficiency; not about ammunition but about tactics.

- 02 -

Why must the food delivery war be fought on efficiency? Because of a fundamental reality: The net profit margin is only 3%. The food delivery business is inherently low-margin and lacks the financial foundation for prolonged cash-burning.

Even if the industry operates steadily, annual total profits are only about 35 billion yuan. Take Meituan as an example: In 2024, its net profit was 35.8 billion yuan, a record high since listing. Broken down per order, it earned just over 1 yuan per order, with a net profit margin of 3%-4%—razor-thin.

Why is the food delivery sector so low-margin?

1. Rider costs cannot be reduced.

In the first half of 2024, Meituan’s financial report showed: The average revenue per delivery was about 3.86 yuan, while the average cost was about 4.13 yuan—a loss of approximately 0.34 yuan per order, or a 9% loss rate.

This means the delivery link alone consumes most of the profit margin.

2. The cost chain is long and inflexible.

Beyond delivery costs, Meituan also spends on marketing and subsidies—red envelopes, discounts, and user acquisition campaigns costing billions annually. It invests in technology and platform operations—algorithm scheduling, servers, and customer service systems to ensure stability. It also incurs fulfillment costs—holiday surcharges, delay compensation, and post-sale refunds—all rigid expenses that cannot be avoided.

3. Food delivery users are price-sensitive.

The average order value (AOV) for food delivery has a ceiling of around 30 yuan. According to the 2025 China Food Delivery Industry Trend Report, Meituan processes 90 million daily orders with an AOV of about 30 yuan.

In summary, the food delivery business earns “hard-earned money,” akin to scraping honey off a blade—minimal profit and high risk. The old internet playbook of “burning money to capture territory” doesn’t work here. Why? Because there isn’t enough “honey” to scrape.

Meituan’s data shows it earns just over 1 yuan per order. Can it really afford to subsidize each order by an additional 2 yuan to acquire users?

Thus, the food delivery war is ultimately a contest of “systemic efficiency.” It’s not about who has more money or offers bigger subsidies but about who can integrate delivery, technology, and operations more efficiently.

- 03 -

Furthermore, the original intent of this food delivery war lacks long-term viability. Its underlying driver is anxiety over e-commerce traffic.

In the first half of 2025, Douyin’s e-commerce GMV reached approximately 4 trillion yuan, nearing Pinduoduo’s scale, while its ad revenue surpassed Alibaba’s. This means Taobao and JD.com now face direct threats in traffic acquisition.

With user attention shifting, traditional e-commerce must find new growth channels.

Taobao and JD.com, seeing the massive traffic in food delivery, aimed to combine instant retail and food delivery traffic to boost e-commerce sales.

But reality has been harsh: CITIC Securities estimates that in 2024, instant retail contributed less than 1% to e-commerce GMV. In other words, food delivery traffic has barely translated into e-commerce growth. It’s not a new gateway for e-commerce but a new illusion.

Why is this the case? Instant retail and traditional e-commerce may both involve selling goods, but their underlying logics are entirely different.

From a user demand perspective, the former addresses “emergency, situational” needs, while the latter caters to “planned, reserve” consumption.

Under these conditions, instant retail competes on ultra-efficient operations (speed and precision), whereas traditional e-commerce focuses on product selection over fulfillment.

To illustrate: Instant retail is like serving hot soup—every step must be precisely timed, and the soup must remain scalding when delivered to the customer. It’s all about efficiency. Traditional e-commerce is like selling rice sacks—moving more sacks is what matters, and speed is less critical. It’s more about scale and subsidies.

But applying e-commerce’s cash-burning tactics to instant retail is like shaking the bowl while carrying hot soup: The more you spill, the greater your losses.

- 04 -

In conclusion, JD.com and Alibaba are fundamentally different from Meituan.

From the direction of their financial disclosures, Meituan is pursuing a path of food delivery to instant retail, while JD.com and Alibaba are making “peripheral attempts” under an e-commerce logic.

The financial reports reveal that Meituan is focusing on flash sales, grocery retail, and Keeta’s internationalization.

International users are collecting orders via Keeta.

First, the flash sales business continues to grow rapidly.

Sales from “brand official flagship flash warehouses” have surged 300% compared to the initial launch, covering hundreds of high-AOV product categories. Among them, sales of gold, coffee machines, and athletic footwear have increased more than tenfold year-over-year.

Second, internationalization is accelerating. In the third quarter, Keeta (Meituan’s international version) launched in Qatar, Kuwait, and the UAE in the Middle East, with operations officially starting in Brazil in late October.

The ultimate lesson from this food delivery war transcends the industry itself. It serves as a warning to all players in low-margin sectors: Future competitive moats will not be built by burning cash but by forging efficiency.

The essence of business competition will ultimately revert to its most fundamental form—the optimal allocation of limited resources. This is the true force that can endure cycles in low-margin industries.

This article does not constitute any investment advice.