The Race for Space Dominance: China’s Bold Leap

![]() 01/23 2026

01/23 2026

![]() 336

336

Space Beckons, and Time is of the Essence.

By Zhang Jingbo, Hua Shang Tao Lue

In Texas, at SpaceX’s Starship base along the Gulf of Mexico, thousands of engineers are relentlessly working around the clock. Meanwhile, as Musk’s fleet surges ahead:

China has finally made its decisive move.

[01 A Stunning Move]

In late 2025, a news item posted on the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) website sent ripples of alarm across the globe:

China submitted a single, sweeping application for frequency and orbital resources for approximately 203,000 low-Earth and medium-Earth orbit satellites!

How significant is this? Let’s examine the data:

By early 2026, there were about 14,000 satellites orbiting the Earth, with over 60%—nearly 9,400—belonging to Musk’s Starlink program.

Starlink has ambitious plans to launch a total of approximately 42,000 satellites.

In other words, China’s application is five times larger than Starlink’s planned constellation and 15 times the current global total of in-orbit satellites.

While this is merely an application—not guaranteed approval, and approved projects may not be fully deployed—the news still sent shockwaves across the world, even prompting actions such as the U.S.’s strategic space maneuvers.

Following China’s announcement, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) swiftly approved SpaceX’s additional deployment of 7,500 Starlink satellites.

At the same time, Musk announced that 4,400 Starlink satellites would be lowered from 550 km orbits to 480 km!

Musk claimed this move was to reduce collision risks, but many analysts interpret it as an aggressive orbital squeeze strategy.

International media attention surged.

Reuters, BBC, and other outlets used terms like "record-breaking" and "unprecedented," viewing it as a significant escalation in the space resources race.

The Economist (UK) argued:

This 200,000-satellite application is not merely a technical competition but the opening salvo for control of the sky in the 21st century.

In reality, China’s application is both a national strategic move and a response to urgent circumstances.

The capacity ceiling for near-Earth orbit satellites stands at a stark 60,000.

This physical limit, determined by Earth’s gravity and radio frequency interference thresholds, leaves no room for negotiation. The ITU, which oversees global coordination, follows a "first-come, first-served" principle for allocating satellite positions.

In other words, low and medium orbits, along with radio frequencies, are scarce global resources—once filled, they’re gone for good.

The current competitive landscape:

The 500-600 km "golden orbit" offers signal latency as low as 20 milliseconds, making it ideal for satellite communications. Over 70% of this prime real estate is now occupied by U.S. Starlink.

Prime frequency bands for civilian communications (L, S, C, etc.) have already been claimed by Western nations, setting extremely high barriers for new entrants.

If China doesn’t accelerate its efforts, it may face a future without available frequencies for 6G development.

Applying for 200,000 satellites at once may seem exaggerated, but when even Rwanda—a poor African nation—has applied for 327,000 satellites under French influence, the intensity of this global space race becomes clear.

More urgently, the ITU’s 2019 milestone mechanism requires:

Any declared satellite must launch its first unit within seven years and complete full deployment within 14, or face automatic cancellation.

This is not flexible guidance—it’s a strict use-it-or-lose-it deadline.

Space won’t wait. The window won’t reopen. Missing this chance means ceding control of 6G’s future and the trillion-dollar aerospace economy.

Moreover, our rivals aren’t giving us time to catch up.

[02 Global Race]

On January 15, 2026, shortly after China’s 200,000-satellite declaration, Musk responded to a netizen’s question with a shocking plan:

In about three years, Starship will launch more than once per hour!

In 2025, SpaceX conducted 165 launches—nearly double China’s total—deploying over 3,000 satellites.

At its peak, SpaceX achieved a remarkable record of 16 launches in a single month, even launching from California and Florida on the same day.

The shortest turnaround time at Cape Canaveral was just 45 hours.

If Musk’s vision of over one launch per hour materializes, SpaceX could reach nearly 10,000 launches annually.

Behind this lies unimaginable hardship and relentless effort.

At SpaceX’s Texas Starship base, thousands of engineers and technicians endure:

Extreme heat, mosquitoes, dust storms, loud factory noise, and welding sparks. Many tasks combine heavy labor with precision operations.

During launch peaks and critical phases—like pre-flight tests or post-explosion repairs—engineers often work 16+ hours daily, sleeping just a few hours over several days. Some describe it as warlike, with management frequently saying, "Mars won’t wait."

Musk’s mantra: "Maximum speed. Failure is learning."

This culture of rapid failure and iteration has allowed SpaceX to saturate and dominate the industry:

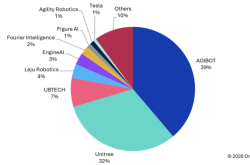

Starlink now has nearly 10,000 in-orbit satellites, over 60% of global active satellites.

More alarmingly, Starlink’s cost advantage.

Just a decade ago, we watched SpaceX’s repeated failures in stainless steel hulls and reusable technology with skeptical interest.

Today, it has not only achieved these goals but commercialized them, creating unmatched cost efficiency.

Take Falcon 9: Through reusability, its launch cost per kilogram has dropped to $1,400–3,000, with even lower internal costs.

When Starship matures, costs could fall to $100–200 per kilogram.

In contrast, China’s commercial launch costs hover around $10,000 per kilogram. Even with rapid progress by private rocket firms, they remain significantly higher than SpaceX.

Musk is just one rival China faces.

Beyond SpaceX, Amazon’s Kuiper Project is rising. The EU is investing billions in IRIS², while Japan, India, and others accelerate.

Near-Earth orbit is like a crowded train—everyone’s fighting for seats. Each enemy satellite in orbit reduces our chances.

Winning means securing orbital high ground and 6G standard-setting power. Losing risks technological sovereignty being strangled at key junctures—there’s no middle ground.

[03 Must Succeed]

With no retreat possible, we must advance.

Even before the 200,000-satellite application, China had pressed the accelerator in its space race.

Hainan’s Wenchang, once a swaying coconut grove and coastal wasteland, is now a bustling construction site for an international commercial spaceport.

▲Source: Xinhua News Agency

Crews work 24/7 in three shifts. In temporary buildings, teams debate plans until midnight, sleeping in corners and eating bread when hungry.

Everyone shares a sense of urgency.

From barren land to first successful launch in just 878 days, they set a global record for commercial launch site construction.

Now, Phase II is underway, aiming for launch capability by late 2026, with annual capacity exceeding 60 launches.

"Every additional pad increases our odds," a young builder remarked.

Besides Hainan, China has launch sites in Yantai (Shandong), Jiuquan (Gansu), Taiyuan (Shanxi), Xichang (Sichuan), and more.

Meanwhile, guided by national policy, private commercial aerospace firms are rapidly emerging, advancing across the full spectrum—from rocket manufacturing to launch services and satellite operations.

In November 2025, a landmark event occurred: China’s National Space Administration established a dedicated commercial aerospace department:

The Commercial Aerospace Bureau.

This is the world’s first national-level regulator for commercial space. Its creation is far more than a bureaucratic shift—it’s a clarion call, signaling:

China’s commercial aerospace has entered a new phase of scale, industrialization, and marketization, becoming a key force in the space race.

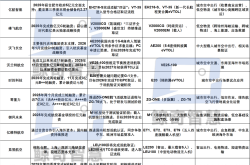

In December 2025, just a month after the bureau’s formation, China’s commercial space sector entered its first-ever intense launch period.

The Long March 12A (state-backed) and Zhuque-3 (private, by LandSpace) both targeted reusable rockets, representing national and private sector efforts.

Reusability is critical for reducing launch costs and scaling satellite deployment. While neither launch achieved full recovery, key technologies were broken through, gathering valuable data.

By 2026, more reusable rockets are poised for flight—success is now a matter of time, and not much.

Even Musk tweeted twice during Zhuque-3’s maiden flight, stating:

"They (Zhuque-3) incorporated Starship elements like stainless steel structures and liquid oxygen-methane propulsion into a Falcon 9-like framework, enabling it to outperform Falcon 9."

More telling than the 200,000-satellite application is China’s existing satellite constellation planning.

The plan calls for three major constellations—Guowang, Qianfan, and Honghu—totaling over 38,000 satellites.

Key milestones: Global coverage by 2027, core networking by 2030, and full deployment by 2035.

This means averaging 10 satellite launches daily to meet targets.

This is not just commercial competition—it’s a struggle for national destiny.

From breaking nuclear monopolies with "Two Bombs, One Satellite" to achieving manned spaceflight dreams, to today’s space race... The abacuses in the Gobi Desert calculated national survival rights. Today, satellites in orbit contend for national development rights.

Time waits for no one.

Ten years, 3,650 days, 10 satellites daily—this is China Aerospace’s KPI, and a race for our national future.

To some extent, how high our rockets soar determines how high we stand in the future world.

[References]

[1] "Growing with China’s First Commercial Space Launch Site," People’s Daily

[2] "Hainan Commercial Space Launch Site Phase II Advances," Xinhua News Agency

——END——

Welcome to follow [Hua Shang Tao Lue] for insights into influential figures and strategic legends.

All rights reserved. No unauthorized reproduction.

Some images sourced from the internet.

For infringements, please contact for removal.