Can Stainless Steel Used in the Kitchen Propel Huang Jingyu to 'Space'?

![]() 01/26 2026

01/26 2026

![]() 521

521

The 'Space Land Grab' Has Commenced

For a mere 3 million yuan, you can send Huang Jingyu into space.

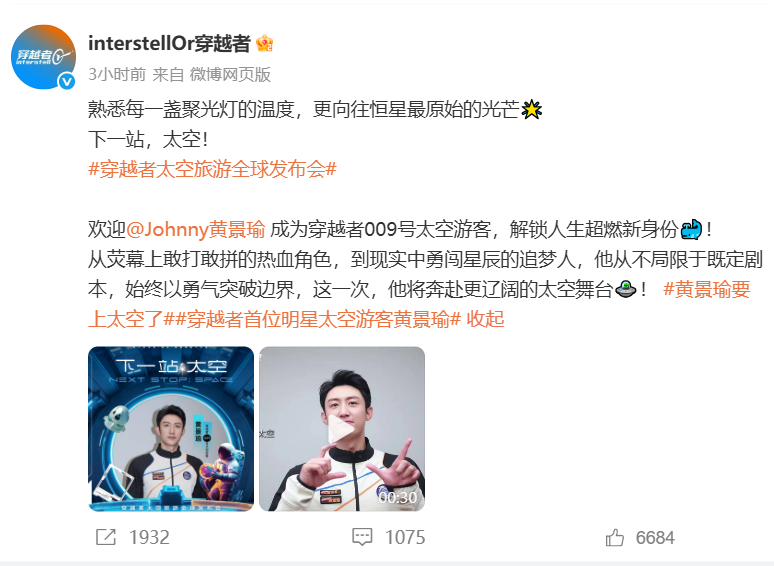

On January 22, @interstellOr Crosser officially unveiled actor Huang Jingyu as the 009th space tourist. In a video recording, Huang expressed his honor at becoming a space traveler, set to journey to the starry expanse aboard a Chinese spacecraft.

Don't get the wrong idea—this isn't a publicity stunt for a new drama; it's a genuine endeavor to send him into the vastness of space.

This marks the first significant breakthrough for commercial spaceflight in China. However, if you look across the ocean, you'll see that this industry, which holds the future of humanity, has already become a fervent pursuit for investors.

According to the UK’s Financial Times, SpaceX, the global leader in commercial spaceflight, plans to engage four top investment banks—Bank of America, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, and Morgan Stanley—to jointly lead its 2026 Initial Public Offering (IPO).

The IPO is expected to achieve an astonishing valuation of $1.5 trillion, breaking the record for the largest IPO in human history and necessitating the involvement of the global financial sector’s most elite group of banks to manage this unprecedented influx of capital.

In China, the fuse for investor enthusiasm has also been ignited.

Over the past two months, the stock prices of all companies remotely related to commercial spaceflight have surged dramatically. Aerospace Electronics rose from 10 yuan to 32 yuan, Aerospace Development from 8 yuan to 40 yuan, and AECC Aero Science and Technology from 26 yuan to 50 yuan—all reflecting strong investor confidence.

Beyond mere speculation, the latest project information from the SSE STAR Market reveals that LandSpace, one of the most closely watched space enterprises, has officially changed its IPO review status to 'inquiry'.

As the frontrunner in China’s race to become the 'first commercial spaceflight stock,' this progress signals that Chinese commercial spaceflight is collectively moving from labs and launch sites to the forefront of capital markets.

From celebrity spaceflights to trillion-dollar IPOs, from Silicon Valley dreams to Chinese speed, why is commercial spaceflight experiencing a collective 'boom' at this moment? Is this an expensive capital spectacle or humanity’s inevitable journey toward a multi-planetary civilization?

01

From 'Costly Experiments' to 'Priced Space Routes'

Spaceflight is no longer solely an extension of national will; it has officially become the most expensive consumer product in human history. Huang Jingyu’s 'boarding' marks the moment when science fiction transforms into consumer reality.

When Crosser announced Huang Jingyu as the 009th space tourist, the entertainment industry focused on the 'extreme tough-guy persona,' but industry observers noted that Chinese commercial spaceflight had finally leaped from 'B-end support' (business-to-business services) to 'C-end monetization' (business-to-consumer sales).

For a long time, spaceflight has been perceived as an unattainable engineering marvel, a symbol of national strength. Now, it bears a price tag: '3 million yuan per ticket.' This signifies a milestone transformation for Chinese commercial spaceflight: from the technical validation phase of 'getting there' to the commercial operation phase of 'selling it'.

Looking back half a century, spaceflight has been shrouded in the shadow of being 'expensive and inefficient.' During NASA’s Space Shuttle era, a single launch cost $1.5 billion, and the price to send 1 kilogram of material into space exceeded that of gold.

This high cost stemmed from a 'handcrafted' manufacturing mindset: each rocket was a precision instrument tailored for a single mission. To achieve extreme thrust-to-weight ratios, scientists piled on extremely expensive composite materials like carbon fiber and titanium alloy.

However, when these multi-million-dollar 'artworks' turned to ashes in the atmosphere after completing their missions, commercialization remained a pipe dream.

This illusion of 'expensiveness' was ultimately shattered by Elon Musk using the most basic material—stainless steel.

Early SpaceX was also obsessed with carbon fiber. Musk initially designed the Starship with an advanced carbon fiber shell, light as a cicada’s wing and strong as steel. But on a winter night in late 2018, Musk scrapped all the blueprints.

He discovered that carbon fiber exhibited extreme instability under extreme cold (liquid oxygen environments) and re-entry heat, with an incredibly complex manufacturing process and shockingly high defect rates. More critically, carbon fiber cost $135 to $200 per kilogram.

Thus, humanity’s craziest 'material downgrade' occurred: Musk chose 301-series stainless steel.

This material, commonly found in kitchenware, costs just $3 per kilogram. Though heavier, stainless steel gains strength at ultra-low temperatures and far outperforms aluminum alloys and carbon fiber in re-entry heat resistance.

More importantly, stainless steel can be welded outdoors like a water tower, eliminating the need for expensive clean rooms. This shift transformed the Starship from a 'lab darling' into a 'shipyard industrial product.'

When spaceflight materials dropped from 'priced per gram' to 'priced per kilogram,' the cost curve of space launches plummeted vertically.

Suddenly, aerospace seemed within reach. When SpaceX slashed launch prices to unimaginable lows, the industry’s logic shifted. What once required 'national efforts' to open now became a business accessible to those with sufficient computing power and industrial capability.

This 'industrialized dimensional strike' has also reached China.

Domestic companies like LandSpace embody this logic. LandSpace’s insistence on developing liquid oxygen-methane engines essentially pursues ultimate cost-effectiveness: cheap fuel, no carbon deposits, and easy reuse.

When LandSpace’s IPO status changed to 'inquiry,' it signaled that Chinese capital markets now recognize this logic: spaceflight is no longer pure money-burning but a 'big logistics business' that extracts cost surpluses through technological innovation.

Huang Jingyu’s participation is a public preview of this 'logistics business' targeting consumers.

When a 3 million yuan ticket no longer seems absurd under celebrity influence, the commercial spaceflight closed loop is complete: rocket companies pave the way (cost reduction), operators fill the cabins (efficiency gains), and capital markets value this future trillion-dollar market.

This is more than a new drama promotion—it’s a pre-sale for humanity’s expansion of living space. It tells us: tickets to the stars are now on sale, and the second half of the game depends on whether we’ve secured enough 'standing tickets.'

02

When Commercial Spaceflight Enters the 'Dark Forest'

However, on this journey to the stars, humanity’s first bottleneck isn’t technology but the extremely limited 'physical slots.'

The universe seems vast, but the 'gold seats' closest to Earth are nearly occupied. This is no longer scientists’ exploration but a 'star-level land grab' betting on national fortunes.

Why the urgency? Why are Chinese and U.S. commercial space giants racing against time in this seemingly prosperous market?

The answer lies in the International Telecommunication Union’s (ITU) ruthless, jungle-law rule: frequency and orbital resources follow 'first come, first served.'

Imagine an undeveloped wilderness with no detailed allocation plan—whoever circles land, plants a flag, and builds a house (deploys satellites) first claims it.

Though low Earth orbit is vast, 'high-quality orbital slots' and 'clean frequencies' that avoid signal interference and collision risks are extremely scarce.

SpaceX’s $1.5 trillion valuation stems less from its rockets’ aesthetics than from its unprecedented 'violent land grab' via Starlink.

Currently, Starlink has thousands of in-orbit satellites and plans to reach 42,000. This means Musk has planted flags across Earth’s near-orbit 'prime real estate.' Later entrants face complex avoidance protocols or nowhere to deploy.

This resource 'greed' has triggered a global panic grab.

On January 10, an ITU disclosure rocked the space community: from December 25–31, 2025 (the year’s final week), China officially submitted an application for 203,000 new satellites’ frequency and orbital resources.

This filing, covering 14 satellite constellations and multiple institutions, is China’s largest and densest international frequency-orbit application to date.

Why so many? Because it’s a 'seat-grabbing' process.

Under rules, satellites must be launched within a deadline, or resources expire. China’s 203,000-satellite application essentially secures 'survival quotas' for its future digital space.

Without filing, future Chinese satellites would need to coordinate with occupied frequencies, a technically and legally passive position.

Deeper anxiety lies in the fact that this is no longer just commercial competition but an invisible arms race—the ultimate ace in space defense.

By 2026, space defense has been redefined. Recent regional conflicts revealed 'satellite internet’s' dimensional strike capability in modern warfare.

A broadband network supported by tens of thousands of satellites offers unparalleled wartime resilience compared to traditional ground cables or large monolithic satellites. You can destroy a base station or shoot down a $1 billion high-orbit satellite, but not a 'net' of low-cost, miniaturized satellites.

This network provides more than communication—it’s modern warfare’s 'God’s Eye.' It guides missiles, transmits real-time drone footage, and offers millisecond-level communication for soldiers. When competitors deploy a 'dense net' overhead and you have only a few scattered satellites, the information asymmetry becomes a battlefield death sentence.

This explains why China StarNet, GalaxySpace, and private commercial space forces are racing at 'near-crazy' speeds in 2026. We’re not just chasing SpaceX’s launch frequency but vying for global space communication 'discourse power' in the next decade.

Every applied satellite slot is a stake on the space map. If you don’t claim a frequency, your spacecraft risks communication blackouts or electromagnetic shielding when passing through occupied zones. If you don’t secure an altitude, your observation equipment drowns in others’ signal oceans.

Moreover, this involves brutal 'space blockade' risks. If low orbit is saturated by one country’s satellites, orbital debris and sheer satellite count make safe entry nearly impossible for latecomers.

Thus, the 2026 domestic commercial space boom is deeply serious.

Capital is flooding in because everyone sees the truth: this isn’t just a trillion-dollar emerging industry but a 'survival rights' game.

As LandSpace’s IPO enters 'inquiry' and Aerospace Electronics’ stock soars amid volatility, higher forces are leveraging capital to urgently address China’s low-orbit constellation shortcomings within a narrow time window.

Under this grand narrative, Huang Jingyu’s 'spaceflight' resembles a heartwarming science popularization, making the public aware: a fierce competition no less intense than the chip fabrication war is unfolding overhead.

Those 203,000 applied satellites aren’t just for China’s millennia-old space dreams but to ensure equal access and decision-making power in the future 'universal operating system' covering the globe.

03

Final Thoughts

To the public, Huang Jingyu’s 'spaceflight' may seem like a costly 'adventure,' but historically, it resembles the first horns blown by 15th-century Iberian ships amid fog.

The difference: those ships carried spices and gold, while today’s liquid oxygen-methane rockets bear data, computing power, and the ultimate expansion of humanity’s physical boundaries.

SpaceX’s $1.5 trillion valuation and domestic efforts by LandSpace and others signal the same message: capital is no longer satisfied with internal competition in mature markets—it smells blood and opportunity on the eve of humanity’s 'interstellar era.'

This race has no finish line.

When costs plummet due to stainless steel and liquid oxygen-methane, and our 203,000 satellites weave a dense grid over low orbit, space will cease to be an exclusive zone and become as accessible as electricity or the internet.

By then, we’ll no longer discuss celebrities 'going to space' but whether humanity has finally secured a multi-planetary backup.

The stars remain silent, but they await those bold enough to turn 'money-burning' into 'road-building.' This interstellar relay race has just sounded its starting gun.

- END -