Earning 500 million in Brazil, they just want to make a fortune quietly

![]() 10/08 2024

10/08 2024

![]() 565

565

Editor | Liu Jingfeng

On some travel websites, Brazil is rated as one of the must-visit destinations in life.

Located on the other side of the globe, Brazil boasts landscapes, cultures, and markets vastly different from those of China. In the first eight months of this year, 4.45 million foreign tourists entered Brazil, marking a 10.7% increase from the same period in 2023. During this year's National Day holiday, Brazil emerged as a popular destination for outbound Chinese tourists.

However, today, we're not discussing Brazil's tourist attractions but rather the Brazilian market, particularly changes in e-commerce, that are of concern to those venturing overseas.

According to incomplete statistics from Xiaguang News, since August this year, at least six summits and salons related to "going overseas to Latin America" have been held in Shenzhen alone. Similarly, in the recently concluded September, no fewer than five companies chose Brazil as the destination for their "overseas inspection teams" amidst the overseas expansion trend.

Even on August 31, a Latin American summit held in Bantian, Shenzhen, was fully booked, with merchants eager to learn about the new market state even standing outside the venue. Throughout the approximately four-hour summit that afternoon, this "congestion" persisted. Of the six guests who spoke at the event, three focused their presentations on the Brazilian market.

Even MercadoLibre's second-quarter financial report released in early August 2024 noted that Brazil's GMV growth reached 36%, the highest level since 2021; the number of items sold in the Brazilian market led the pack, with a year-on-year increase of 37%.

Latin America is undeniably on fire. For cross-border e-commerce, it's currently the hottest spot in the region. If Latin America is "the last blue ocean in the world," then Brazil is the rapidly growing "Shenzhen" within that blue ocean.

So, has Brazil become the new hotbed for cross-border e-commerce?

You probably rarely hear stories of Chinese companies making money in Brazil, although legends do exist. However, these are often vague tales of "Zhang San, Li Si, Wang Wu," whose names are easily forgotten, achieving prosperity through unknown means.

The reality of e-commerce in Brazil is that while there's a lot of buzz, actual progress is slow. Brazil is hot, but few dare to venture there.

In fact, this aligns with the development pattern of most markets: hype precedes substance. The market gains momentum, attracting ambitious entrepreneurs. As supply increases, it fuels desire, cultivates consumer loyalty, and expands the market.

However, in Brazil, "hype precedes substance" seems to take longer. Geographically, Brazil ranks sixth among the 10 countries farthest from China, at a distance of 16,632 kilometers (from the geographical centers of the two countries). The farther the business, the more crucial it is to consider input-output ratios, high risks, and low controllability.

Thus, Brazil is indeed hot, fueling the enthusiasm of countless overseas ventures like a blue ocean. Yet, while many observe, few actually do business there. Most merchants hesitate at Brazil's gateway, lacking the courage to step into the market.

In this article, we aim to present a true picture of Brazil to merchants who hesitate at the gate. We hope that with this prior understanding of an unfamiliar market, you'll still find the courage to venture forth.

The phrase "the last blue ocean market in the world" doesn't exclusively refer to Latin America; Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia are also often described in similar terms.

As long as development hasn't reached its ceiling and Chinese products can find a use there, it can be considered a "last" + "blue ocean." It sounds like an opportunity not to be missed, a once-in-a-lifetime chance that vanishes forever if let slip away.

However, just because there's room in a blue ocean market doesn't mean Chinese merchants can easily succeed, or that there's necessarily demand. For instance, while Africa is a blue ocean, its basic logistics infrastructure needs development, requiring patience for returns. Russia has demand, but political turmoil hinders economic flow; survival takes precedence over growth. The Middle East is also a blue ocean for cross-border e-commerce, but its small population limits market potential.

In comparison, Latin America is not just the last blue ocean but one with visible promise. For cross-border e-commerce, Latin America, especially Brazil, represents the fastest-growing market over the next 5-10 years, according to Xiaguang News.

Brazil is too far away for Chinese merchants. Flying from Shenzhen to Brazil takes at least 34 hours with two transfers. In the past, distance deterred many Chinese merchants from entering the Brazilian market; they required a compelling advantage over closer markets.

Today, that advantage is becoming clear.

In terms of elimination, European and American e-commerce has developed for 11 years, while Southeast Asia has boomed for eight. Both are now relatively mature, attracting numerous Chinese merchants. As one Brazilian e-commerce practitioner described it, "The competition is fierce."

Focusing on Latin America, Mexico has the most free trade agreements globally, while Chile has no anti-dumping measures against Chinese products and boasts a relatively complete logistics network and transportation system, making its entry barriers lower than Brazil's. A 2023 report by consulting firm kaweslab revealed that AliExpress, SHEIN, and Temu collectively accounted for over 50% of Chile's cross-border e-commerce market. In the same year, Amazon Mexico's seller count grew by 52%, reaching nearly 27,000 sellers.

Brazil, though the largest consumer market in Latin America, has complex customs and tax policies, deterring many Chinese merchants. "Most merchants entering Latin America target Mexico and Chile first before considering Brazil," explained one source. "Brazil's popularity this year stems from increased competition in Mexico and Chile, driving merchants to Brazil."

The market is vast in Brazil; once products enter, they seldom go unsold. Despite the distance and entry barriers, sales aren't a concern. With over 150 million poor people, demand for cost-effective products is high, and they're willing to buy now and pay later. Wealthy individuals also seek premium products to satisfy their upgrading needs.

Moreover, Brazilians embrace digitalization and enjoy entertaining apps. A prime example is Kwai, the international version of Kuaishou, which focuses on the Brazilian market and boasts over 60 million monthly active users, equivalent to 30% of Brazil's population. International cloud service providers like Tencent Cloud have also established data centers in Brazil, offering cloud services like computing, storage, big data, AI, and security to Brazilian and other South American clients.

Due to this digital leaning and product demand, Brazil's wholesale market is undergoing a retail transformation from offline to online. This year, several e-commerce platforms have set their sights on Brazil. For instance, Temu made Brazil its 70th site, while MercadoLibre invested approximately US$4.6 billion (its largest investment ever) in new distribution centers in Brasilia, Pernambuco, and Porto Alegre. Amazon Brazil also joined the Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) Remote Fulfillment program in 2024, allowing Brazilian sellers to share US FBA inventory.

Latin America is one of the farthest regions from China. The geographical distance creates a significant information gap, reducing competition and business opportunities, creating a distant utopia for Chinese merchants.

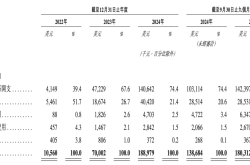

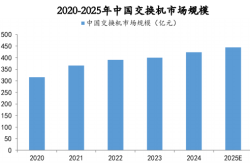

As Latin America's largest e-commerce market, Brazil presents ample opportunities for Chinese merchants. From 2020 to 2022, Brazil's e-commerce sales rose from approximately BRL 126 billion to BRL 169.6 billion. According to the Brazilian E-commerce Association (ABComm), sales in the Brazilian e-commerce market are expected to reach BRL 204.3 billion in 2024.

Some liken Brazil to Shenzhen in China. Brazil's diverse population is innovative, favoring fresh, personalized products, validating its growth potential and vast market. Yet, it's also the hardest market to enter, testing aspirants with a rigorous "entrance exam" requiring a perfect score for full preparedness.

Where does Brazilian e-commerce currently stand? One practitioner told Xiaguang News, "It's like China in the 1990s."

Offline channels still dominate consumption in Brazil, accounting for around 90% of transactions. This low level of online penetration and relatively primitive social state characterize Brazil's true consumption pattern—a fully competitive market with ongoing safety concerns like robbery and theft.

A Brazilian cross-border e-commerce service provider shared with Xiaguang News, "Sometimes, thieves steal things that are laughable. Our surveillance footage once captured a thief who spent about an hour climbing over a wall to steal... a faucet worth around RMB 20. But that day, we spent over RMB 2,000 fixing the water leak it caused." He added, "But for him, that faucet was worth the time and effort."

Container thefts and lost goods are common in Brazil, reflecting its "old-fashioned" state. Yet, this also underscores Brazil's enormous development potential compared to mature markets.

Despite rising e-commerce penetration, Brazil's demand for foreign goods is more of an "upgrade" rather than a rigid need.

Agriculturally, Brazil boasts one of the world's largest arable land areas, ranking fifth globally with approximately 557,000 square kilometers, even with much arable land yet to be developed. Industrially, while Latin American countries generally have low industrialization levels, Brazil's industrial system is sufficiently complete. It's the world's sixth-largest steel producer, Latin America's largest, and the world's ninth-largest automobile producer, with notable scale and strength in shipbuilding, oil, cement, chemicals, metallurgy, power, textiles, and construction.

Notably, since the 1980s, Latin American countries have generally relied on imports but have prioritized domestic industrial development, aiming to reduce dependence on imports. Thus, whenever Brazil can meet its self-sufficiency needs, it reduces its demand for foreign products.

While insufficient, Brazil's "just enough" approach explains its "blue ocean" status for years. As a result, Chinese merchants focusing on Brazil view this opportunity more long-term, "akin to seizing China's market in the 1990s, a decade-long chance."

Changes are underway. At Xiaguang News' July Latin American salon, a MercadoLibre official manager shared a case where a seller's sales increased from around 1,000 orders per month last year to 1,000 orders per week this year.

However, these minor e-commerce advancements barely address the significant challenges facing most merchants.

In Brazil's consumer market, while Chinese merchants may seem absent, they're actually present. They face competition from three sources: local merchants, local Chinese merchants, and other cross-border e-commerce merchants.

Local Brazilians account for around 80-90% of the market, deeply understanding local practices but with limited product offerings and poor operational capabilities. Local Chinese merchants arrived early, familiar with local laws and taxes but lacking e-commerce knowledge. Thus, there's an information gap among these three groups, each striving to fill their respective shortcomings.

Currently, Chinese cross-border e-commerce merchants encounter a situation where, once a product category gains popularity through cross-border e-commerce, local Chinese merchants source products from Yiwu, sell them through their channels, and initiate price wars. Ultimately, cross-border merchants find their competitors are still in Yiwu, albeit through different channels.

Therefore, in Brazil, the profit window for any product rarely exceeds two months, posing the first major challenge for cross-border merchants.

The second challenge lies in Brazil's protectionist policies in this somewhat primitive land.

Brazil is well-known as the "country of taxes." For instance, since August 2023, Brazil has imposed a 17% ICMS (Imposto sobre Circulação de Mercadorias e Serviços) on cross-border packages from local e-commerce platforms. Packages under USD 50 are exempt from customs duties but subject to 17% ICMS; those above USD 50 pay 60% customs duties plus 17% ICMS.

Furthermore, Brazil has established certification systems for foreign goods, including INMETRO, ANVISA, and ANATEL. Products that may pose safety risks to non-professionals require INMETRO certification, covering items like plugs, sockets, toys, pacifiers, electrical equipment, household appliances, consumer electronics (audio-visual products), IT devices, and lighting fixtures. Telecommunications products require Anatel certification and OCD conformity certificates. For medical, food, cosmetic, and hygiene-related equipment or items, import, transportation, sale, and storage require ANVISA approval and authorization.

"The costs incurred by these various processes are substantial," a Brazilian market seller calculated for Xiaguang News. "Compared to mature markets, the same product may need to be priced 3-4 times higher when sold in Brazil to achieve profitability."

Therefore, while recognizing the trend towards online commerce in Brazil, it is also essential to acknowledge that the process of e-commerce in Brazil is concurrent with both online and localization efforts.

This year's e-commerce platform policies reveal that virtually every player is advancing localization efforts. For example, Amazon Brazil's FBA program requires a local Brazilian company, while cross-border accounts can only use overseas warehouses for dropshipping; Shopee's cross-border accounts must be linked to a local company; MercadoLibre's cross-border accounts only support small packages and do not yet support local dropshipping...

Furthermore, starting in 2023, Brazil began imposing taxes on cross-border small parcels, with the cheapest option being a 44% import duty and tariffs of up to 93% for packages over $50. The decline of cross-border small parcels signals a shift towards local supply chain centers and the rise of local accounts.

It can be said that e-commerce in Brazil is growing and opening up, but this openness is premised on protecting the domestic economy. In Brazil, the global is also local, but the global must first be local.

Even at the content level, those with distinct local characteristics prevail. For instance, Kuaishou's localization in Brazil is more profound than TikTok's. Kwai focuses primarily on Brazilian local content, including the popular short dramas of recent years, where Kuaishou hires Brazilian actors for filming. This deep localization has yielded results, making Kuaishou the top-ranked short drama brand among all social platforms in Brazil among users' hearts.

In summary, facing the distant utopia, there are two core issues that Chinese merchants must consider to succeed: first, how to thoroughly localize without any intermediary; second, finding a balance between cost-effectiveness and profitability to make the journey worthwhile.

In a sense, Brazil represents a saturated blue ocean: while appearing to be a blue ocean, the space for merchants to excel is limited. Some practitioners told Xiaguang News that "there are sellers in this market with volumes of 300-500 million," but the few who have made money are reluctant to share their experiences in this remote land, as silence is golden in leveraging information gaps.

According to data released by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics on August 29, 2024, Brazil's total population stood at 212 million as of July 1, 2024. However, some Brazilian e-commerce practitioners told Xiaguang News that the actual figure is likely higher, "with a significant 'black market' population, leading to an imprecise estimate of over 400 million people in total."

To tap into the wallets of 400 million people, one must first address the issue of payment. According to a joint survey by the Getulio Vargas Foundation Business School and Brink's Brazil in 2021, 53.4% of Brazilians prefer to pay bills and make purchases with cash. Among them, approximately 45 million Brazilians do not have bank accounts and rely solely on cash transactions due to their inability to use electronic payment methods.

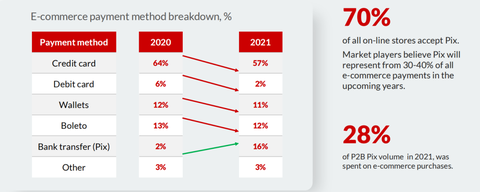

In November 2020, Brazil's Central Bank launched the instant payment system Pix. Data shows that as of August 2023, in a survey on the frequency of local consumer payment methods in Brazil, 70% of Brazilian users had chosen Pix for payments, just 1 percentage point behind cash payments, making Pix the second most popular local payment method after cash.

Global fintech company ebanx also released a report stating that in 2023, Brazil's instant payment system Pix held a 29% market share of online payments in the country, with nearly 80% of first-time online shoppers choosing Pix over the past three years. It is projected that by 2026, Pix will account for 40% of online payments in Brazil.

The prevalence of online payments, akin to the infrastructure of e-commerce, has laid the foundation for the penetration of e-commerce in Brazil.

The second cornerstone is the continuous improvement of the logistics system. In terms of last-mile delivery, the monopoly of the Brazilian Postal Service has given way to the entry of many Chinese-funded enterprises, leading to a steady enhancement of overall logistics performance.

A noteworthy case is Anjun Logistics. In 2019, it entered the Brazilian market through a partnership with the local payment platform ebanx. After extensive communication and efforts with the Brazilian government and postal service, it took approximately 15 months to establish and integrate the China-Brazil cross-border small parcel express line. Moreover, Anjun continues to expand its investments in Brazil, acquiring two local companies to address policy, customs clearance, and transportation issues. Additionally, it has established warehouses and local teams, launched B2B local delivery services and consolidation warehousing, gradually building a comprehensive logistics delivery system.

Logistics is also progressing in localization efforts. An employee of a Brazilian overseas warehouse company told Xiaguang News that warehouse rental fees in Brazil have increased by 80% over the past year due to the rapid development of e-commerce.

"The Brazilian market offers a first-mover advantage, particularly in logistics. For example, the cost difference between LCL (less than container load) and FCL (full container load) is substantial. The more containers one can secure, the lower the logistics costs," said the employee. Therefore, the more scalable the operation, the lower the costs become.

Similarly, standardization is also a trend. Customs clearance is the most challenging aspect of the entire cross-border supply chain. As the core of localization, overseas warehouses are increasingly providing customs clearance services to more merchants. The employee also mentioned that "tax-related matters also require professional overseas warehouse companies to provide additional services, aiming to minimize unnecessary costs. Therefore, when choosing a Brazilian overseas warehouse, merchants prioritize additional services over storage service pricing."

Currently, since there are not many Chinese merchants in Brazil, overseas warehouse companies primarily identify business opportunities through "word-of-mouth" referrals, such as introductions from platform providers. Standardized overseas warehouses can become platform-certified warehouses and cooperate with platform providers earlier. Due to the distance, the early layout of Brazilian overseas warehouses precedes the development of e-commerce in mature markets.

Additionally, in cross-border e-commerce, merchants must address issues related to store accounts and fund repatriation, forming the third cornerstone. For store accounts, service providers have solved the problem of bulk registration of local stores. A Brazilian e-commerce service provider told Xiaguang News that previously, an account cost over 100,000 yuan, but now it is much cheaper.

In terms of fund repatriation, cross-border payment companies such as PingPong, CoGoLinks, Ebury, Pyvio, and XT Brazil Collections have all launched solutions tailored to cross-border e-commerce. For instance, CoGoLinks has introduced a collection and payment solution for MercadoLibre's Brazilian local stores, allowing merchants to directly bind their CoGoLinks collection accounts in the store backend to experience fast Brazilian Real collection and settlement services, with accounts directly belonging to the sellers themselves. Ebury has acquired a local fintech company in Brazil to better serve Brazilian enterprises with cross-border payment services. Pyvio can tailor exclusive solutions for enterprises at different development stages, meeting their varying financial needs in the Brazilian market expansion process and resolving various cross-border payment issues...

It is evident that e-commerce in Brazil is thriving at its own pace. However, according to the channel logic prevalent in most mature markets, where online growth precedes offline branding, the current scale of e-commerce in Brazil falls short of this ideal.