E-commerce New Forces Can No Longer Remain Hidden

![]() 03/25 2025

03/25 2025

![]() 714

714

It was just eight years ago, in 2017. According to CICC research reports, during the heyday of e-commerce at that time, Taobao and JD.com dominated the market with a combined share of 93%. However, the tide turned swiftly and silently. By 2025, that figure had plummeted to 50%.

On the other side of this eight-year upheaval stands the rise of a cluster of "e-commerce new forces," codenamed: "Tencent, Douyin, and Pinduoduo."

This may be the most significant paradigm shift in China's internet industry in recent cycles. After a "revolution of equal rights" from "customer collusion" to "user co-governance," the new e-commerce forces have taken center stage: WeChat, which was still "restrained" eight years ago, now boasts an e-commerce ecosystem that has permeated to the "atomic level"; Pinduoduo, which hadn't yet IPO'd eight years ago, now firmly holds the second position in China's e-commerce industry; Douyin, whose future was uncertain eight years ago, has emerged as China's third-largest e-commerce platform.

Is the phenomenon of these new e-commerce forces, represented by "Tencent, Douyin, and Pinduoduo," an inevitable outcome of technological advancement, or a triumph of the thinking and cognition of a new generation of entrepreneurs?

The 2018 Upheaval

First, let's review the changes in e-commerce market share in recent years:

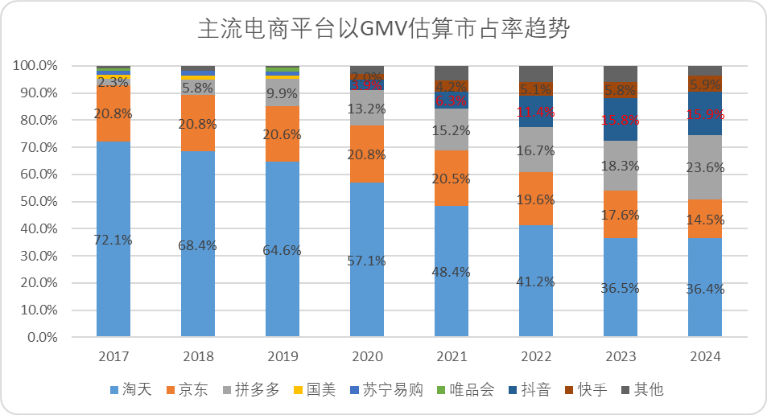

In 2017, shelf e-commerce was at its peak. According to CICC research reports, the combined market share of Taobao and JD.com, measured by GMV, once reached a staggering 93%. Three years later, in 2020, that number was 85%. In 2023, the sky changed abruptly as Pinduoduo surpassed JD.com with a market share of 18.3%, breaking Taobao and JD.com's unassailable monopoly and taking the second spot in the industry. By 2024, according to data released by 36Kr, Pinduoduo's GMV reached 5.2 trillion, and Douyin's GMV was 3.5 trillion, both occupying the second and third positions after Taobao. As of the end of 2024, based on the estimated total GMV of 22 trillion in the e-commerce market, the market share of Taobao and JD.com is precisely around 50%—the new forces are at the gates, and the traditional shelf e-commerce is no longer in its prime.

Figure: Estimated market share trends of mainstream e-commerce platforms based on GMV, source: CICC, JinDuan estimates

The reasons behind the quiet reshuffling of the e-commerce landscape are indeed complex, but at its core, we can straightforwardly present our post-review viewpoint—this is a war of deconstruction and reconstruction of the power chain in the e-commerce industry, akin to a "meticulously designed" strategy. In other words: while the defenders were still calibrating the accuracy of their courses on the old compass, the new forces quietly completed the race by changing their routes and sails. For observers familiar with the history of e-commerce over the past decade, the logic is not difficult to understand:

Over the years, the mainstream narrative of e-commerce platforms has revolved around the primacy of "platform value," constructing a classic "people-goods-place" theory that permeates every pore of the industrial chain from top to bottom, ultimately becoming an unassailable industrial benchmark. On both the demand and supply sides, especially the supply side, under the "guidance" of this theory, each occupies its place, takes platform rules as the bible, sits in rows, and divides the fruits.

Throughout the process, the only ones able to compete with the platform are the top suppliers—only brand merchants have the ability to pay for the platform's marketing expenses and "traffic tax" through product premiums. Most of the platform's revenue comes from this, which naturally transfers more power to top brands. And in order to attract top suppliers, they have to continuously invest in traffic to ensure platform value, raising costs and becoming even more dependent on top brands. Over the long term, a notable feature of the narrative logic of the e-commerce industry was the collusion between the platform and the top suppliers on the supply side. The game of power has an end, and this end is what we later saw: with the evolution of technology and changes in cognition, external new forces violently cracked the existing rules, deconstructing the inherent power chain and ultimately reconstructing the game rules on both the demand and supply sides through a "revolution of equal rights."

Revolution of Equal Rights

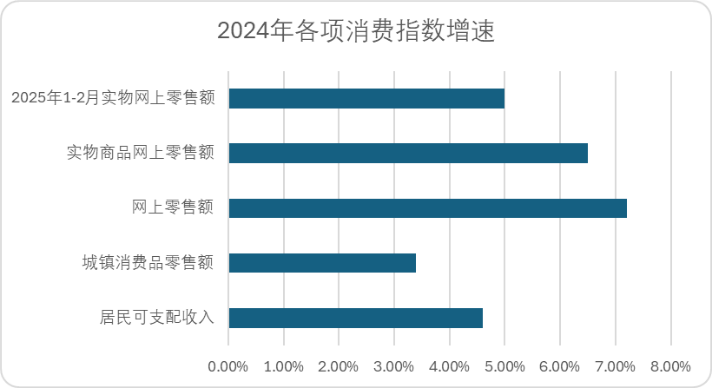

It needs to be clarified that mainstream public opinion is not optimistic about the growth rate of consumption, but from a data perspective, the growth trend of the overall e-commerce market has not changed: in 2024, the total retail sales of consumer goods in urban areas still grew by 3.4%, disposable income of residents grew by 4.6%, and online retail sales grew by 7.2%, of which online retail sales of physical goods grew by 6.5%.

Figure: Growth rates of various consumption indices in 2024, source: Choice Financial Client

This involves a key question: in a highly competitive e-commerce market, where do the increments of the new e-commerce forces come from? Some believe it is from sinking markets, after all, the culture of affordable substitutes is prevalent, and enterprises with low per-customer prices have ushered in a golden growth period; others believe it is the female economy, with the lipstick effect etched in the minds of scholars studying consumer history; still, others believe it is demographic structure, whether it's Generation Z or the silver economy, the crux is linked to consumer age. Admittedly, these statements make sense, and from any facet of consumption phenomena, we seem to be able to find increments. But all incremental demand linked to age, products, or even prices is superficial, and the actual increments brought about are very limited. Above the surface, from a higher-dimensional perspective, one can understand the core essence of incremental demand:

All research on demand is inseparable from Maslow's hierarchy of needs—everyone actually has five levels of needs, and middle to high-income consumers pursuing self-realization also have physiological and safety needs. Every individual has diverse needs, not just a single group satisfaction.

This naturally means that regardless of whether a person is poor or rich, young or old, born in the south or north, they all have needs for survival, security, respect, and self-realization. In front of needs, everyone is equal. This is the practical significance of "equal rights for demand":

There is no hierarchy between physiological and psychological needs. Just like Zhou Libo and Guo Degang's "coffee and garlic theory," there is no such thing as "drinking coffee is elegant, eating garlic is vulgar"; essentially, it is the difference in individual needs in different scenarios. In other words, if a person's real need is just thirst, the platform doesn't have to recommend a high-priced coffee or alcoholic beverage; mineral water at an appropriate price may be more in line with the user's needs. Everyone's needs deserve to be seen. Not dividing customers by price and not screening needs by brand can reach the broadest range of needs, seeing increments, and realizing increments. The new e-commerce forces not only see the consumption differences between Shanghai people and Anhui people but also see the diversity of each user's own needs. It is precisely because of their focus on real needs that the new forces can achieve equal rights for demand, and then go on to explore and provide a richer supply to more efficiently meet users' real needs in different dimensions. Under the premise of equal rights for demand, the "equal rights for supply," which is its twin, naturally becomes the optimal solution for the new e-commerce forces. Obviously, a single brand supply cannot meet the broadest range of needs. Only by adopting a decentralized mechanism to treat every kind of supply equally—be it brands or white-label products—and leaving it to consumers to choose, with real demand determining supply, can the maximization of supply and demand matching be achieved. Among the new e-commerce forces, whether it is through the unique content breadth of content platforms or specific price discovery mechanisms (for detailed logic, see "E-commerce Never Ages, It Just Enters a New Cycle of 'Price Discovery'"), all supplies are given the same exposure opportunities. As long as they can meet users' most basic and detailed needs at reasonable prices, white-label products and individual merchants can also gain more exposure. Users can see "thousand-yuan trendy shoes" in the live stream of fashion bloggers, and they can also find "9.9 yuan snacks" in a rural courtyard full of life. The logic of equal rights for supply on the supply side of the new forces also conforms to the real development law of the supply side—in the past few years, the core logic of the development of China's supply-side industry has been from centralization to decentralization:

From 2019 to 2023, the compound annual growth rate of the number of wholesale and retail legal entity enterprises in China reached 15.05%, and a large number of newly established domestic white-label brands emerged.

According to the "2024 Douyin E-commerce Annual Report" by Chanmama, the GMV growth rate of new brands further increased by 12% compared to 2023. In most sub-consumer segments, the fastest-growing dark horse brands are all new brands.

It can be seen that only by following the trend can one find the winning move. Under equal rights for demand and supply, as the platform side, the platform rules must inevitably evolve and adapt accordingly. Therefore, during the rise of the new forces in the past, we have successively seen a series of unprecedented new rules and concepts, such as the Hundred Billion Subsidy Program, agricultural support, only refund, and universal traffic, gradually become the standard configuration of e-commerce platforms. This is equal rights for rules. In a nutshell, its core essence is: always stand on the side of consumers. The collapse of most business empires actually points to a core contradiction: the supply side cannot self-purify. Because the primacy pursued by the supply side has never been demand satisfaction but profit, it will fall into the trap of "static efficiency optimization" most comfortable for vested interests, as evidenced by cases like Kodak and Standard Oil. But by using demand to force supply, Pareto improvement can be achieved. Nobel laureate in economics Friedrich Hayek once proposed the "Consumer Sovereignty Theory" based on Adam Smith's "The Wealth of Nations": the production decisions of enterprises are essentially an extension of consumer demand, and merchants must compete for consumers' limited budgets by continuously optimizing. Therefore, only by standing on the side of consumers on the demand side and using the most authentic user feedback to force the supply side to optimize and iterate can the platform ultimately achieve maximized trade. Above, the new e-commerce forces represented by "Tencent, Douyin, and Pinduoduo" have reshaped a new power structure starting from equal rights for demand, with equal rights for supply and rules as manifestations, by deconstructing power. This has allowed them to continuously capture new increments in the fiercely competitive e-commerce market, overturning the existing competitive landscape.

User Co-governance

At this point, a key question emerges: why can the new e-commerce forces recognize the strategic significance of equal rights for demand without falling into the traditional narrative logic? Some believe that the new forces stand on the experience accumulated in the old world and are naturally more capable. Others believe it is the iteration of technology, with the emergence of recommendation algorithms breaking through the shackles of information matching under the search model. However, these viewpoints are actually based on the reverse deduction of existing results. The rearview mirror perspective cannot answer why, in a business society where metabolism is faster, there are still enterprises that can achieve enduring success. Taking Pinduoduo as an example, as a relatively early player in the new forces to enter the e-commerce market, it has still been able to achieve high growth on a high base over a longer period. This is by no means a pure technological victory; essentially, it is the result of value orientation driving behavior patterns, namely:

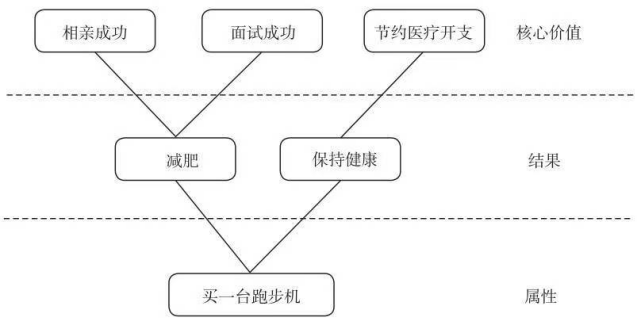

Not pursuing "customer collusion" but practicing "user co-governance." A review of past e-commerce chess games shows that since its inception, Pinduoduo has emphasized and adhered to the principle of "ultimate consumer-side rights": through the social fission model, users have become the promoters of the platform; in the product design of "only refund," users have become the supervisors of the platform; in the construction of the C2M and agricultural product industry chain, users have indirectly become decision-makers through consumption behavior. Why is "user co-governance" so important, even being considered the winning move for the rise of new forces? "Consumer Behavior" has a dedicated chapter on the deduction of the consumption link. The core viewpoint is that the incremental demand model follows an inverted pyramid logic. Different starting points of demand may lead to the same endpoint on the supply side. Taking treadmills as an example, standing on the side of consumers, the platform will realize that the core value of consumption may be dating, interviews, health, and thus dig out derivative demands such as clothing accessories, knowledge payment, and medical services. While focusing on supply-side brand promotion, the demand that can be dug out may only be a treadmill.

Figure: Evolution of the consumption link - demand and supply, source: "Consumer Behavior"

The inspiration for the e-commerce industry from this case stems from the realization that e-commerce platforms can continually unlock the core value of transaction behavior only by aligning with the interests of consumers. When the demand side enjoys an enhanced user experience, it provides constructive feedback to the e-commerce platform, offering more room for improvement. Simultaneously, supply-side merchants are better able to pinpoint incremental demand, fostering a virtuous cycle. The traditional business model of e-commerce platforms, as discussed in the previous chapter, essentially revolves around "customer collusion" aimed at maximizing profits and revenue, inherently limiting the exploration of the broader underlying real demand. Inevitably, a shift occurs: as industrial power transitions from "centralized control" to "ecological co-construction," the monopolistic barriers erected by vested interests are gradually eroded by technological inclusivity and infrastructure openness.

Conclusion

Let's recap the key viewpoints of this article:

E-commerce platforms like TPD (Tencent, Pinduoduo, Douyin) have deviated from the conventional industry narrative by reshaping the power chain and achieving efficient supply-demand matching through a three-tiered model of equal rights: demand, supply, and rules. This approach allows them to capture incremental growth.

The new wave of e-commerce players has ushered in an era of equal rights by shifting their mindset from "customer collusion" to "user co-governance." This transformation drives the e-commerce industry away from a power distribution logic and towards a logic of value co-creation.