Lost in Idealism, Li Xiang Stages a Comeback

![]() 11/28 2025

11/28 2025

![]() 557

557

In the business realm, there's no single, foolproof path to lasting success, not even for those who've once soared to great heights.

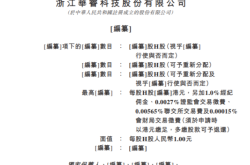

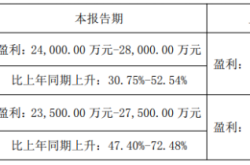

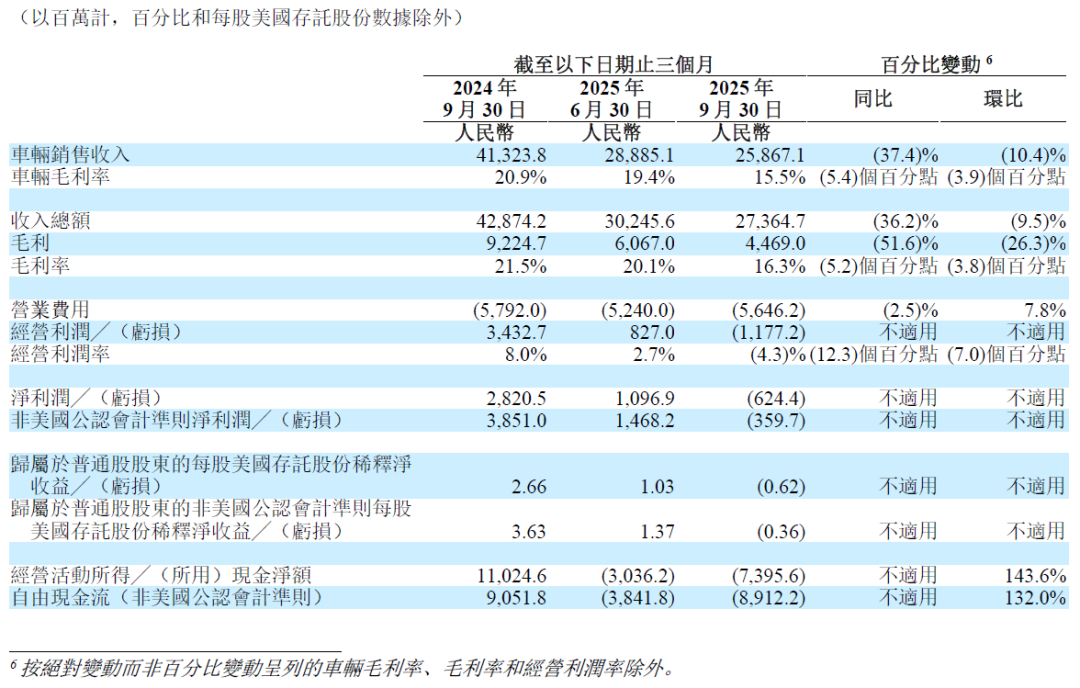

On November 26, Li Auto unveiled a staggering third-quarter financial report: revenue plummeted to RMB 27.365 billion, marking a 36% year-on-year decline; a net loss of RMB 624 million was reported, a stark reversal from the RMB 2.8 billion net profit achieved in the same period the previous year.

Moreover, as 2025 unfolded, Li Auto found itself facing a barrage of challenges:

Early in the year, Li Auto relinquished its crown as the top-selling new energy vehicle (NEV) brand, ceding the title to XPeng Motors for several consecutive months and altering the competitive landscape among the 'NIO, XPeng, and Li Auto' trio. In the latter half of the year, the long-anticipated second all-electric model, the Li i8, underperformed upon its launch, triggering a continuous decline in the company's stock price. Recently, the recall of the Li MEGA further strained the company's profitability, compounding the pressure already evident in the third-quarter results.

The former frontrunners among new energy vehicle startups—'NIO, XPeng, and Li Auto'—are now each navigating through critical transformational phases. However, in contrast to the swift responses from He Xiaopeng and Li Bin, Li Xiang's introspection seemed delayed until the company 'transitioned from profit to loss,' at which point he conceded that 'the past version of himself was the worst.'

Yet, amid intensifying market competition and dwindling capital patience, how much time does Li Auto have to reinvent itself?

1. A Top Student Loses Ground

In the first half of 2025, Li Auto delivered a financial report that fell short of expectations. By the third quarter, the company faced its first quarterly loss since going public, with all performance indicators raising red flags.

Beyond the overall decline in revenue and net profit, total vehicle deliveries in the third quarter stood at 93,211 units, a 39.0% year-on-year decrease. Worse still, Li Auto's fourth-quarter sales guidance projected only 100,000-110,000 units, showing no significant improvement from the third quarter.

Additionally, impacted by the Li MEGA recall, the gross profit margin in the third quarter plummeted by 3.8 percentage points sequentially to 16.3%. However, excluding the recall's impact, the vehicle gross profit margin would have been 19.8%, slightly rebounding by 0.4 percentage points sequentially.

Concerns over Li Auto's third-quarter report stem not only from declining sales and the shift from profit to loss, which can be attributed to short-term challenges. The deeper issue is that Li Auto appears to be experiencing a systemic slowdown.

From the MEGA to the delayed and underperforming all-electric i-series, and even the gradually fading extended-range L-series, where does Li Auto's problem lie?

One contributing factor is the turning point for extended-range vehicles. In recent years, under intense competition from formidable rivals like Leapmotor and Seres, coupled with the relatively shallow technological moat of extended-range technology, the dividends (benefits) of the extended-range route are gradually diminishing.

In the first half of this year, the market share of extended-range vehicles in China's NEV market dropped from 10.7% in 2024 to 9.8%. Since June, domestic sales of extended-range vehicles have declined year-on-year for five consecutive months.

Li Auto was not oblivious to this trend; it launched its first all-electric product, the Li MEGA, as early as March 2024. However, as we all know, the Li MEGA failed to make an immediate impact due to its design, disrupting Li Auto's布局 (layout/strategy) in the all-electric market.

Ultimately, the delayed Li i8, arriving a year late, faced competition from the 'last-ditch effort' LeDao L90, as well as the Seres M8 all-electric version and the Tesla Model YL, missing the optimal market entry window.

The product strategy is even more central to the issue. Currently, both the Li i8 and the subsequently launched Li i6 have their own shortcomings.

The Li i8, launched in July, urgently announced a unified configuration version just one week after its debut, simplifying the previous three versions into one and upgrading features like refrigerators and VLA from optional to standard. This move was seen as a response to external criticism of the i8 being 'overpriced and under-equipped.'

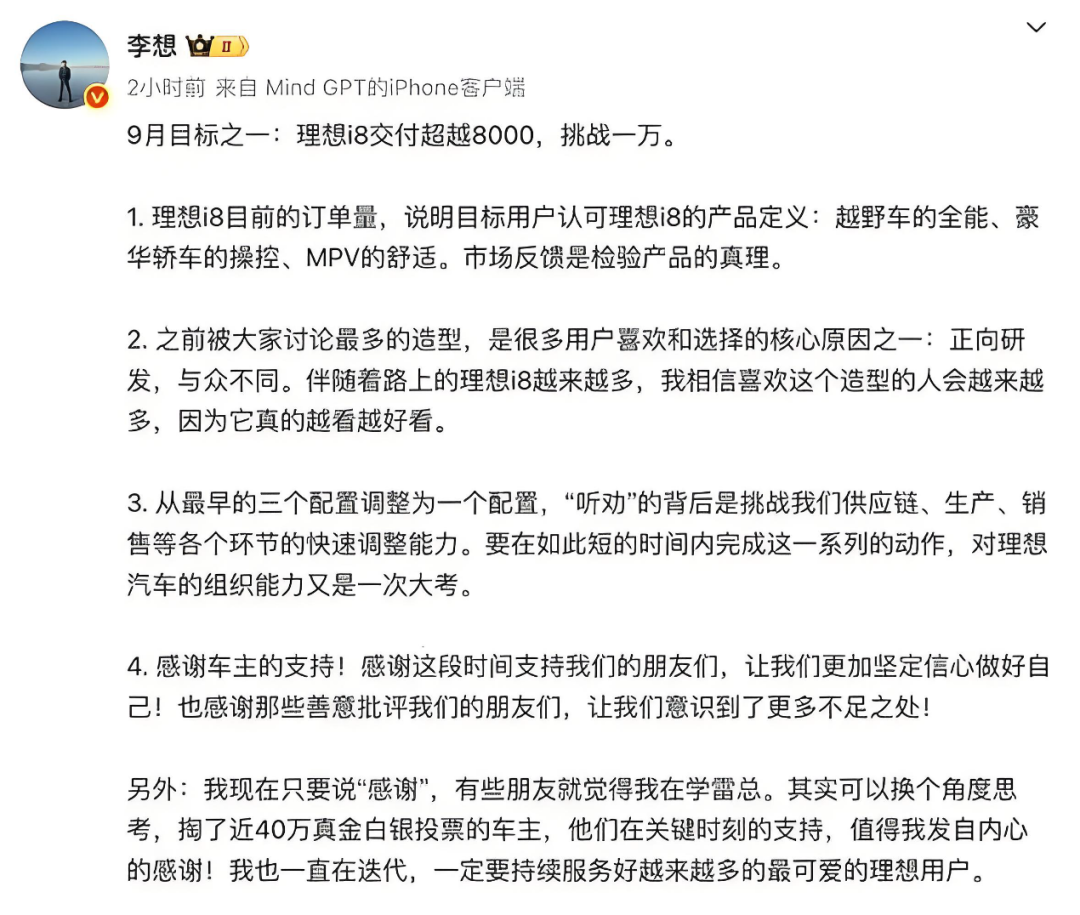

Despite the price reduction, the Li i8's deliveries fell short of expectations. Li Xiang had set a target of over 8,000 deliveries in September, ideally reaching 10,000. However, the Li i8 only delivered 5,716 and 5,749 units in September and October, respectively.

From an external perspective, the Li i8's price was not low enough to ignite the market, and the product itself was merely 'adequate.' Most consumers had also grown weary of Li Auto's 'copy-paste' product strategy.

Thus, the Li i6, launched at the end of September, took over the 'price reduction' baton. Although it secured nearly 50,000 reservations within 48 hours, production capacity constraints significantly limited its delivery capabilities. Li Xiang mentioned in a September public discussion that this year's production capacity for the i6 would likely fall short of market demand.

Even so, many consumers switched from the i8 to the i6. A Li Auto salesperson revealed that after the i6's launch, most users switched to the i6, with 80% of in-store visitors coming to see the i6.

However, Li Auto did not reap the benefits. To some extent, the more popular the i6 becomes, the more awkward the i8's position, even affecting the L-series' foundation.

In consumers' eyes, the i6 and i8 share similar appearances and design styles, differing mainly in seating capacity (five vs. six seats) and powertrain (all-electric vs. extended-range). With a price difference of RMB 70,000-80,000, consumers naturally opt for the cheaper option.

2. Is the 'Huawei Model' No Longer Viable?

The internal competition between the Li i-series models, even spilling over to the L-series, reflects Li Auto's complacency in product refinement.

As we all know, Li Auto's product strategy revolves around 'copy-paste car manufacturing.' When a hit model gains momentum, 'copy-paste' variants can quickly capitalize on market enthusiasm and user trust, seizing more market segments with lower trial-and-error costs.

However, in the business world, no hit model remains popular indefinitely. As 'copy-paste' models proliferate, product experiences increasingly overlap, leading to internal cannibalization within the product line.

When high-priced models fail to deliver perceived value, and even high-priced products underperform compared to lower-priced counterparts, a product value inversion occurs, gradually eroding the brand's control over premium products.

Thus, behind Li Auto's slowing sales lies not only issues with product positioning and promotion timing but also the challenge of redefining the 'product formula.'

Facing this dilemma, Li Auto held a three-day closed-door strategic meeting in mid-October, reflecting on declining sales, R&D, product strategies, and other issues, admitting to 'slowed efficiency.' One outcome of this introspection was Li Auto's decision to overhaul its previously revered Huawei model. On November 11, Li Auto announced an internal restructuring: the 'Organization Department' and 'Human Resources' under the Organization and Finance Group were merged into a single 'Human Resources' department, integrated into the Product and Strategy Group; the Organization and Finance Group was renamed the CFO Function Group, clarifying its core role in financial control; Yang Haishan was appointed as Head of Human Resources, reporting directly to CEO Li Xiang.

Behind these adjustments, Li Auto further clarified the finance department's central role in cost control and capital management, as well as its focus on human resources management, strategic focus, and decision-making efficiency.

In July, Li Auto abandoned Huawei's PBC (Personal Business Commitment) performance model and reverted to OKR (Objectives and Key Results). Unlike XPeng and NIO, which first targeted supply chain reforms, Li Auto was more eager to revitalize its internal operations through structural adjustments.

Looking back, in 2022, Li Auto reached a consensus to fully adopt Huawei's IPD (Integrated Product Development) system. Simply put, building a skyscraper requires ensuring every component, like bricks, screws, and steel, is flawless. Thus, the core of the IPD system is not pursuing efficiency but ensuring steady project progress.

Later, Li Auto adjusted this system, treating R&D, sales, marketing, and other personnel as components, forming project teams for different product lines to enhance collaboration between horizontal project departments and vertical functional departments.

In Li Auto's view, this system avoids overly complex processes that reduce decision quality and efficiency, allowing teams to focus more on user value and operational efficiency.

However, the reality is that Li Auto, with its inherent internet-based flat organizational structure, could already solve problems more efficiently. After adopting Huawei's system, it inadvertently created 'walls' between different project teams, reducing interaction between product lines and even exacerbating internal friction.

With the industry's rapid model update cycles ('three generations in a year'), Li Auto's 'copy-paste' model could no longer keep pace with competitors. If different project teams operated independently, ensuring correct model iterations became even more challenging.

For every company, there is no universally 'best' management method, only the 'most suitable' one. The key question is whether Li Auto can become a better version of itself after abandoning Huawei's model—a more critical test for Li Xiang personally.

3. Li Auto's Second Entrepreneurial Journey

At the October closed-door strategic meeting, Li Auto mentioned adjusting its model, product, and R&D strategies, accelerating its global expansion, and increasing AI investment.

To some extent, Li Auto was denying its past self. It stated it would no longer follow the 'copy-paste' route but instead adopt a 'one platform, one style' approach for the future. It reflected on its delayed global expansion and even acknowledged strategic missteps in last year's layoffs, which significantly dampened internal morale.

At the 2025 third-quarter financial report meeting, Li Xiang also denied Li Auto's three-year attempt to transition to a 'professional manager' governance system, deeming it incompatible with the current unstable market environment and Li Auto's actual situation (realities). He bluntly described the past few years' performance as 'the worst version of himself.'"

Thus, Li Auto announced a full return to a startup model beginning in the fourth quarter of this year:

Organizationally, founders and the startup team must engage more deeply in work, replacing reports with in-depth dialogues and resource possession with efficiency gains—key elements for enhancing cognition and bold decision-making.

Product-wise, Li Xiang emphasized focusing on user value rather than mere delivery. Only things truly valuable to users warrant delivery, not just completing delivery tasks.

Technologically, Li Xiang proposed a new vision for NEVs, stating that if products merely remain electric vehicles, competition will devolve into a specification war. If Li Auto focuses solely on intelligent terminals, it would merely transplant smartphone functions into cars, offering limited value to users.

He argued for breaking free and transforming cars into embodied intelligent products in the physical world, emphasizing the importance of a complete AI system to truly change users' lives.

To some extent, Li Auto is following the path previously taken by XPeng and NIO, embarking on a new round of self-reform. However, unlike the 'urgency' displayed by XPeng and NIO during their transformation phases, Li Auto's 'second entrepreneurship' appears more composed.

Indeed, compared to the cash flow pressures faced by XPeng and NIO during their reforms, Li Auto still boasts RMB 100 billion in cash reserves.

However, in external eyes, while Li Auto's 'second entrepreneurship' addresses core issues in internal management, it seems to overlook the more pressing need for product reform, instead focusing on longer-term goals of five to ten years. Yet, the future always begins with the present.

Today, most NEV companies are striving to paint a broader technological vision, aspiring not just to 'build great cars' but to transform into genuine tech companies. Such aspirations are undoubtedly inspiring.

However, whether for intelligent vehicles or the nascent robotics business, the ultimate deciding factor has never been the grand narratives at product launches but whether solid products can solve real-world user problems.

For Li Auto to regain its growth trajectory, it cannot merely bet on AI for the future; it must ultimately return to technology and products. This is less about Li Auto's second entrepreneurship and more about founder Li Xiang's self-revolution. His vision will determine Li Auto's future.