Chinese Entrepreneurs in Latin America: The Internet Narrative of 'One Hundred Years of Solitude'

![]() 11/11 2024

11/11 2024

![]() 756

756

Editor | Liu Jingfeng

If you start from Beijing, China, and drill straight down to the center of the Earth, crossing to the other side of the Earth along the same diameter, you would end up on the southeast coast of Argentina in South America, near the Rio Negro River.

These are the two most distant points on Earth, representing the physical limit of distance that a person living in Beijing can reach.

The vast geographical distance makes Latin America a foreign land in the hearts of the Chinese. Wang Ye, who has lived in Argentina since his teens with his parents, still recalls the exhaustion he felt after taking a more than 20-hour connecting flight from Beijing to Buenos Aires.

For Chinese enterprises going global, Southeast Asia is an economically accessible backyard that can be easily reached by air travel; whereas Latin America is the last blue ocean after swimming until the sea turns red.

The vast physical distance also brings differences and gaps in social forms. Football, samba, and drug abuse are the three most well-known labels of Latin America, but most people's understanding is limited to these. Many people who venture into Latin America for the first time are deeply shocked by the culture: in the core district of Mexico City, you can see the walls covered with dense photos of missing persons – these are missing person notices posted by relatives, reflecting the turmoil and unrest in the country; the inefficiency of the government is astonishing – it takes a year and a half to obtain a local residence permit, and a colleague's husband's name was mistakenly registered under one's own name, with no cost to the government personnel for these mistakes.

Urban landscape of Monterrey, an industrial city in northern Mexico

However, to some extent, Latin America is also the emerging market most similar to China: there is a massive single market like Brazil, where per capita consumption capacity and GDP levels are similar to those in China; and compared to Southeast Asia's precocious de-industrialized industrial form, and the Middle East's leap from a traditional tribal social structure directly into a digital economy without going through a modern large-scale industrial society, Latin America, like China, has fully experienced the process of industrialization and urbanization.

Just yesterday (local time November 10), the APEC Leaders' Meeting Week kicked off in Lima, the capital of Peru. Heads of government and senior officials from 21 economies in the Asia-Pacific region, representatives of private enterprises, experts, scholars, media personnel, and others gathered in Latin America to discuss economic development. Nowadays, the changes on this land have become new stories in the conversations of those going global.

Latin America has never lacked adventurers from China.

Briann, a Chinese teacher at the Confucius Institute in Costa Rica, discovered after traveling to many Latin American countries that the vast majority of small supermarkets there are owned by Chinese people.

In the 1970s and 1980s, many villages in Guangdong and Fujian migrated en masse.

For example, Panama is home to people from Huadu, Guangdong, while Costa Rica has many people from Enping, Guangdong. Based on geographical and kinship ties, dozens of supermarkets can send a representative to negotiate with local suppliers to purchase in bulk at a lower price than local large supermarkets. The diligence and flexibility of the Chinese have gradually allowed them to monopolize the small supermarket market in Latin America.

Since the 1990s, economic globalization has accelerated. The first Chinese enterprise to explore Latin America was Huawei. At the end of the last century, Huawei arrived in this remote place, setting up communication networks connecting to cities in remote rural areas where Western communication enterprises were unwilling to set foot, ushering in the Internet era in Latin America.

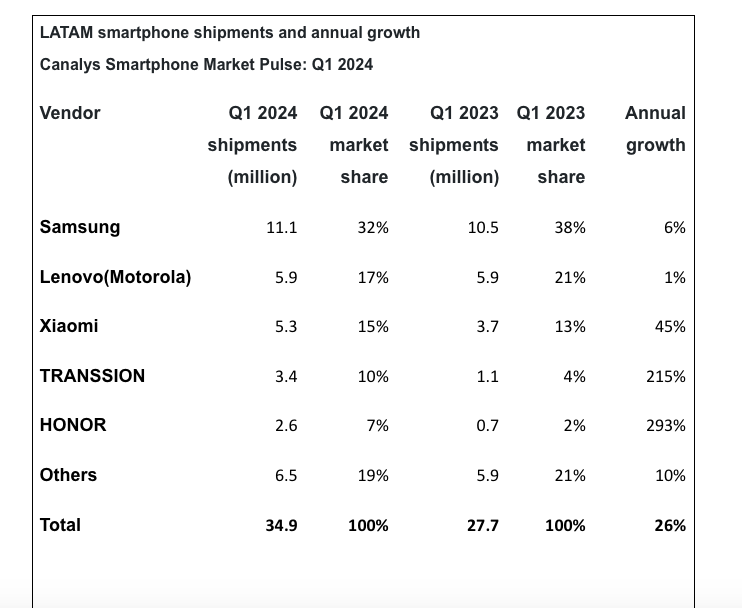

With the Internet accessible, consumer electronics brands represented by Xiaomi, Motorola, Transsion, and Honor also targeted this huge market of over 650 million people. After more than a decade of development, by the first quarter of 2024, four out of the top five market share holders in Latin America's mobile phone market were Chinese brands.

In the first quarter of 2024, among the top five market share holders in Latin America's mobile phone market, except for Samsung occupying the top spot, the second to fifth places were occupied by Motorola, Xiaomi, Transsion, and Honor, respectively. The period from 2010 to 2020 is known as the "golden decade of China's mobile Internet." During this time, Chinese entrepreneurs also exported mature digital economy business models to Latin America. Data collected by the British consulting firm Preqin shows that since the beginning of 2017, China's total venture capital investment in Latin America has surged to $1 billion, compared to only about $30 million in 2015.

"Historically, Latin America has always sought business from Silicon Valley and New York, but Chinese innovation may be more applicable to the realities of Latin America," said Felipe Henriquez, managing partner of venture capital firm Mountain Nazca, in an interview with Bloomberg in 2019."He had a concise summary: "When you go to China, you will see what will happen in Latin America in five years. Today, we focus on China. We focus on Meituan, Alibaba, and Tencent to see what we can do in the future."

As a result, there has been a wave of "Copy from China" in the field of digital economy in Latin America."In early 2018, David Vélez, an entrepreneur from Colombia, read an article about China's financial miracle. He learned that nearly 1 billion people in China were managing their finances through mobile apps like Alipay and WeChat Pay. Vélez was impressed and traveled to China with some team members to witness this increasingly cashless society firsthand.

Vélez's trip to China made him realize that the financial technology opportunities in Brazil were similar to those when Alipay (later renamed Ant Group) was established in China over a decade ago. In the past, financial services in Brazil were controlled by the five major banks, which mostly provided financial services to the wealthy and rarely opened them up to the poor. However, the Internet has started to equalize access to financial services for both the rich and the poor."You can provide high-quality investment products for low-income people. The key to reaching a large population is through mobile phones rather than bank branches, and to keep product functions extremely simplified," Vélez said. Today, Nubank, the leading digital bank in Latin America founded by David Vélez, received an investment of $180 million from Tencent in October 2018 and has grown into one of the fastest-growing financial institutions globally – as of June 30, 2024, Nubank had a total of 104.5 million global customers, a 25% year-on-year increase, and is seen as a beacon of hope to shake up the bureaucratic banking system in Brazil.

In addition to Nubank, Latin America has also emerged with local versions of Meituan like Rappi, a Bilibili-like platform called RisApp, Kalo, the first local short video social platform in Latin America, and e-commerce platforms like Dingdong Maicai.

After 2020, the pandemic accelerated the online shift of consumption and transactions. In the field of e-commerce, SHEIN, Shopee, and AliExpress have all entered Latin America; internet giants TikTok and Kwai also view Latin America as a key market for their e-commerce businesses, actively recruiting talent and upgrading their operations; and up-and-coming player Temu has achieved comprehensive coverage of major countries in the Latin American region.

In the field of fintech, due to the inefficiency of Latin America's traditional financial system and the high demand for banking services and credit from consumers, the number of startups has increased rapidly. For example, Stori, invested in by BAI Capital in 2019, became Mexico's latest unicorn company in 2022; in 2021, BAI invested again in TruBit, a compliant cryptocurrency exchange in Latin America."Nowadays, new energy and green technology have become the next wave of Chinese investment in Latin America. A report on China-Latin America relations released by the US market research institution The Dialogue in January 2024 showed that an increasing amount of Chinese investment in Latin America is flowing into the "new infrastructure" industry, including strategic businesses such as information and communication technology, renewable energy, electric vehicles, and high-end manufacturing.

According to RockFlow Research Institute's analysis, Latin America is going through a series of development stages from simple to complex, roughly in the following order:

First, the consumer retail industry, including e-commerce and many related fields;""Second, economic 'infrastructure,' especially fintech and logistics;""Third, the digitization of small and medium-sized enterprises, such as B2B software for business process automation;""Fourth, hard technology, biotechnology, etc., which generally require strong technical capabilities and large R&D budgets."This means that all business models that have been successful in China are worth replicating in Latin America."

Urban landscape of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

In 2022, Marcus, a Latin American e-commerce entrepreneur, came to Brazil. He found that buying a can of cola here costs about 9 RMB, three times the domestic price. "Every time I buy something in a physical store in Brazil and then compare the price on Pinduoduo, I feel utterly defeated."Marcus believes that Brazilians are daring consumers but cannot buy good things even if they spend money. They live a poor and miserable life with no quality, while spending their salaries in advance and living beyond their means.Due to the underdeveloped manufacturing and light industry in Latin America and the imperfect offline retail industry, this is precisely an opportunity for e-commerce. "Currently, e-commerce in Latin America is still in the stage of filling SKUs. Chinese e-commerce platforms often have tens of millions of SKUs, while Latin American e-commerce platforms only have a few hundred thousand SKUs, and locals have very limited options for shopping online. As long as there are more SKUs, people will prefer to shop online," Marcus said.2022 was also a year when e-commerce platforms with a Chinese background heavily invested in Brazil. According to a report by Brazilian investment bank BTG Pactual, SHEIN's sales in Brazil that year (estimated) reached 8 billion reais (close to 10 billion RMB), a 300% increase from 2021. Shopee, a Southeast Asian e-commerce platform invested in by Tencent, closed its European sites in Poland, Spain, France, etc., in 2022, and withdrew from Argentina, shutting down most of its operations in Chile, Colombia, and Mexico, but its focus and investment in Brazil have not decreased.It is worth noting that both SHEIN and Shopee operate in Brazil through a "local-to-local" model rather than cross-border air transport:"In December 2021, Xu Yangtian, the founder of SHEIN, personally visited Brazil to inspect the local clothing supply chain, meeting with top local clothing suppliers to discuss the feasibility of producing clothing products in Brazil. SHEIN expects that by the end of 2026, about 85% of sales in Brazil should come from local manufacturers and sellers;""In April 2022, Felipe Piringer, Director of Marketing and Strategy at Shopee in Brazil, said that Shopee had covered 2 million local sellers in Brazil, with 87% of sales coming from local sources and only 13% from cross-border products. 'Shopee's business in Brazil is not just a Portuguese translation of a foreign website,'" he said.The heavy investment in local e-commerce by cross-border platforms stems from Brazil's protectionist trade policies as the "country of taxes": According to the latest Brazilian decree, starting from August 1, 2024, small cross-border packages valued at less than $50 will be subject to a 20% import tax in addition to a 17% ICMS (Imposto sobre Circulação de Mercadorias e Serviços) in each state; for import packages valued at more than $50, the portion exceeding $50 will continue to be subject to a 60% import tax and a 17% ICMS, but packages valued at less than $3,000 will be exempted from $20 in taxes."Brazil has raised taxes on cross-border small packages to an unacceptable level, and there is almost no cross-border business from China to Brazil now. If you still want to enter the Brazilian market, Chinese sellers need to find reliable local companies to act as their legal representatives in Brazil, find suitable overseas warehouses, and solve issues related to logistics, payment, and fund repatriation. This requires reliable people in Brazil to help sellers handle a series of things," Marcus saw this business opportunity and devoted himself to the Brazilian e-commerce service industry.However, after more than a year of exploration, Marcus said frankly, "I regret it.""In fact, it was only this year that decent overseas warehouses emerged in Brazil. Due to the lack of a mature warehouse management system, Marcus had to stay in the warehouse every day to check the orders to ensure no mistakes.Moreover, due to Brazil's foreign exchange controls, fund repatriation is also a major challenge. Marcus shared a story: not long ago, he needed to receive a transfer of $30,000 from a partner. He went to the bank in advance to confirm if the receipt was possible, and after receiving a positive response from the bank manager, Marcus waited for three weeks only to be told that the money had been received but he needed to open a quota in advance to withdraw it. "I asked the bank manager why he didn't tell me earlier that I needed to open a quota. He told me he forgot.""Applying for a withdrawal quota requires first declaring one's business operating revenue, which means paying taxes based on the expected operating revenue before the business actually occurs. After repeated back-and-forth, Marcus chose to return the money. Of course, it took another three weeks for the refund.Finding a reliable local legal representative to establish a local company is an even riskier matter. "Can Brazilians abide by the rules when signing a contract? It's too difficult.""I can't cover every aspect and connect every link. In the future, I will only focus on one link. Otherwise, it's too energy-consuming, and it's hard to grow the business. In China, various supporting industries are very mature, but due to fierce market competition, it is extremely difficult to operate a store; while in Brazil, it's the opposite. The supporting industries here are extremely immature, and it takes effort to find the right people to solve these troubles. But from the perspective of store operation, all e-commerce platforms are in a bonus period. As long as you do good market research, making money is not difficult," Marcus said.

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, has many slums built on hills, requiring residents to commute by cable car for daily life

Fortunately, logistics and payment processes are becoming increasingly sophisticated.

In logistics, three Chinese-backed logistics companies—Anjun Logistics, J&T Express, and imile—have significantly improved the timeliness and service quality of Latin American logistics.

For payments, the instant payment system Pix, launched by the Central Bank of Brazil at the end of 2020, is rapidly gaining popularity. Data shows that by the end of 2022, approximately 71.5 million Brazilians had access to financial services through Pix; it is expected to replace credit cards as the primary payment method for e-commerce in Brazil by 2025.

"Pix's penetration in Brazil is akin to WeChat Pay's dominance in China. I asked Brazilians why they prefer electronic payments. They said they used to carry cash everywhere and often fell victim to robberies, incurring heavy losses; now, they only need a mobile phone, and the worst they can lose is their phone if robbed. Therefore, they quickly adopted electronic payments, completing a process that took China five to six years in just two years," said Marcus.

When visiting the famous São Paulo Cathedral in Brazil, it is advised not to take out your phone nearby, as it is prone to theft.

Ultimately, Latin America is far from China, both geographically, culturally, and psychologically, requiring tremendous determination to overcome. Defeats often occur swiftly: for example, a young man who mustered the courage to start a computer business in Brazil was robbed four times in two months and chose to return home, devastated.

This year, Marcus has hosted four or five groups of Chinese e-commerce market explorers from China. However, none of them chose to enter the market.

He observed that 80-90% of those doing e-commerce in Latin America are Chinese businessmen who have lived there for a long time. Those previously involved in retail and wholesale businesses are now transforming their businesses online, riding the e-commerce wave.

Yet, major platforms continue to enter the market. On November 4, the short video app Kwai officially announced the launch of its e-commerce platform Kwai Shop in Brazil, combining short videos with online shopping to bring new changes to Brazilian e-commerce. After entering the testing phase at the end of 2023, Kwai Shop achieved a 1300% increase in daily purchase orders in 2024, with electronics, household items, and cosmetics being the best-selling categories. 70% of small businesses in Brazil have utilized social networks like Kwai to enhance their visibility.

"The threshold for Latin America is indeed high, but it depends on whether people are willing to cross it," said Marcus. "If you make up your mind, you should be able to make a lot of money in the coming years. More people should come to join me in the future."

In the late 1990s, Ye Daqing, who worked for Capital One, a renowned American credit card issuer, witnessed the innovation and development of the American credit card market. Continuously keeping an eye on new opportunities in global fintech, he spotted a new trend in Mexico, often referred to as the economic backyard of the United States: with a population of approximately 123 million, Mexico had only 30 million credit card holders, a penetration rate of 24%; digital banks like Nubank were emerging; and banks such as Citibank, BBVA, and HSBC were very successful in Mexico but mostly served high-end customers. This indicated a vast blue ocean market in inclusive finance waiting to be explored.

"Mexico's industrialization, digitization, and inclusive finance are just beginning. It can be said to have the right 'time, place, and people.' As part of the North American Free Trade Agreement, Mexico benefits greatly from geopolitical changes; geographically, it serves as a gateway between the Americas and Asia/Europe; legally, as a common law country and the only major country that did not impose lockdowns during the pandemic, Mexico quickly attracted talent from the US, China, Asia, and Europe, forming a strong human resource base. With low financial penetration and high demand for loans, the financial industry in Mexico has strong profitability and untapped market potential," said Ye Daqing.

Rose, a Chinese entrepreneur in Mexico, shared that before visiting local banks, she always needs to mentally prepare herself for a long wait and cannot plan her next itinerary in advance due to the lengthy process: there is always a long queue at the bank, and staff lack a service mindset. Compared to depositing money in the bank, locals prefer to keep their money under the pillow. On the other hand, due to high inflation, Mexicans have a strong demand for credit. Wang Ye, who trades in Latin America, found that his workers often need advances on their salaries, "but it's impossible to give them more than they deserve because they might not show up the next day if they get extra money," he said.

On payday, there is always a long queue outside Mexican banks

Even today, when shopping online in Mexico, people still choose Oxxo, the largest local convenience store chain, as a payment method: after clicking on Oxxo on the payment page, they print the bill and pay in cash at an Oxxo store within the specified time to complete the online order, with a 1% handling fee for each transaction.

This is very similar to prepaid card recharges in the era of China's PHS (Personal Handy-phone System), outdated and inefficient.

Therefore, in the second half of 2017, when Ye Daqing's former colleague at Capital One, Chen Bin, approached him with Stori's Business Plan, Ye Daqing immediately agreed with this startup plan for a Latin American digital bank. At that time, Ye Daqing, who had already founded the mobile finance platform Rong360 and led the company to go public, became an angel investor for Chen Bin.

"Stori can be said to have the strongest team in global fintech and digital banking, with CEO Chen Bin, COO Sherman, CTO Nick, and Mexican local Marlene Garayzar, who has experience in both the internet and financial sectors. I joked at the time that compared to Nubank, Stori's founding team was far superior, so there was no reason for them to perform worse," recalled Ye Daqing.

Established in 2018, Stori is positioned to provide inclusive financial services to low- and middle-income individuals not covered by traditional banking systems. In 2020, Stori launched its first credit card product, the only one in Mexico with an approval rate of 99%; in 2022, Stori was valued at $1.2 billion, entering the 'unicorn' club; in 2023, Stori introduced a deposit product with market-leading yields—Stori Cuenta+ with an annual interest rate of 15%, sparking a savings revolution in Mexico; in 2024, Stori jointly launched the first co-branded credit card with e-commerce giant SHEIN. From savings accounts to credit cards, Stori currently provides fast and convenient financial products and services to 4 million users.

In fact, fintech is the most mature startup sector in Latin America. There are over 600 venture capital-backed fintech companies in Latin America, accounting for approximately 40% of all venture capital in the region. In Ye Daqing's view, the wave of fintech startups focusing on inclusive finance in Latin America is just beginning: "Whether it's lending, mobile payments, or wealth management products, including infrastructure upstream and downstream of the fintech industry, such as facial recognition technology and risk management technology, there are opportunities for all."

If the past few years, from Nubank to Stori, represented the first wave of B2C fintech innovation in Latin America, the region is now entering the second wave of B2B fintech: mobile POS, corporate credit cards, and accounts payable and receivable management for SMEs will be the next opportunities for fintech startup investments in Latin America.

Of the top nine startup unicorns in Mexico, six are fintech companies

It's not just fintech; Mexico is currently experiencing a burgeoning development boom. As part of the North American Free Trade Agreement, Mexico's per capita GDP and total trade volume with the United States surpassed China for the first time last year, making it one of the few countries with a population exceeding 100 million and a per capita annual GDP exceeding $10,000. Neither India nor Indonesia can achieve both simultaneously due to their lower per capita GDP.

In the first half of 2024, Latin America attracted $2.18 billion in investment, a 40.7% increase year-on-year compared to 2023, with Mexico being the hottest emerging market, where startups are thriving.

Ye Daqing described Mexico's future potential using Warren Buffett's theory of a "long, wet snowball": "Life is like rolling a snowball; the most important thing is to find thick snow and a long slope." Here, the "long slope" refers to Mexico's vast space for development and long-term growth potential, while the "thick snow" represents the strong profitability and competitive advantage of enterprises. "Mexico's urbanization, industrialization, digitization, mobile internetization, and artificial intelligence are just beginning, somewhat similar to China in 2012, when giants like WeChat, Xiaomi, and ByteDance emerged. Mexico is at the starting point of an explosion," said Ye Daqing.

The economic distance between Mexico and China is also narrowing: before the pandemic, there were only 70,000 Chinese people in Mexico; now, with more Chinese people coming here to invest and start businesses, the Chinese population in Mexico has risen to 200,000 to 300,000; in May this year, China Southern Airlines opened a direct flight from Shenzhen to Mexico City, and in July, Hainan Airlines opened a direct flight from Beijing to Mexico.

Ye Daqing has visited Mexico nine times, each time with different experiences. Recently, on November 7, he delivered a speech at the Latin American Tech Investment Forum at the 2024 Singapore Fintech Festival, comparing Mexico's wave of innovation and entrepreneurship to that of China 20 years ago: "When you arrive in Mexico, you can truly feel the contagious energy of the youth, their dreams, and their drive to succeed."

This is the golden age of Latin America.

In 2014, digital nomad yeye first visited Latin America. Over the next decade, she spent more than half of her time living in various Latin American countries. In her view, this land seems frozen in time, rich and fertile yet stagnant.

"The change here is really slow. Whether it's 2014, 2018, 2023, or 2024, when I go to local supermarkets in Latin America, the popular music playing there is exactly the same. In terms of business forms, the most noticeable change is the gradual development of e-commerce, but it's mostly driven by Chinese companies," said yeye. "This also proves that there is a market for Chinese people doing business in Latin America because there are so many untapped areas, and most locals cannot be your competitors."

For example, on the Mexican island of Cozumel, where yeye lives, getting a taxi is still a headache. Due to the lack of a mature ride-hailing system, local taxi drivers monopolize pricing power, charging 100 pesos (approximately 35 Chinese yuan) for a two-kilometer ride, and drivers do not give change by default, charging per person. To facilitate travel, yeye bought a motorcycle. When encountering overcharging taxi drivers, yeye deliberately rides her motorcycle in front of them and actively informs tourists of reasonable taxi fares.

Cozumel, a Mexican island, yeye

Yeye eagerly awaits Didi's arrival in Cozumel to regulate the taxi market. In fact, Didi, which already holds nearly 50% of the major market share in Latin America, is constantly adapting and integrating with the slow and magical pace of the region with each step of its exploration.

As early as early 2017, Didi invested in 99 Taxi, a local taxi company in Brazil. Initially holding approximately 30% of the equity, Didi had one seat on the five-member board. In 2018, Didi officially took control of 99 Taxi through a combination of cash and preferred stock issuance.

However, the low online payment penetration rate posed a significant barrier between Didi, drivers, and passengers at that time.

To solve the payment issue, in 2019, Didi partnered with Oxxo, leveraging its 18,000 stores in the Mexican market to allow passengers to directly recharge their Didi balances with cash, enabling credit card-free online payments; in 2020, Didi Pay entered the Mexican market, serving as a debit card and mobile banking platform for all registered drivers on the Didi platform. Through Didi Pay, drivers receive their salaries on a daily basis.

Entering the local lifestyle sector has become another moat for Didi in Latin America: in Brazil, Didi provides food delivery services through 99 Food; in Mexico, this service is called DiDi Food. In Latin America, Didi is growing into a super app integrating various services such as ride-hailing, food delivery, credit, and payments, similar to Meituan in mainland China and Grab in Southeast Asia.

But how to adapt to the rhythm of this land remains a difficult problem. Yeye said that it was the collective boycott by local drivers in Cozumel for their own interests that prevented Didi from penetrating the island; In early 2023, taxi drivers in Cancun, a Mexican resort, even blocked the main roads from the airport to the hotel district and harassed and attacked ride-hailing drivers and passengers; In Guadalajara, the second largest city in Mexico, Didi was once denied a license for three months before it was finally issued with the help of local resources.

In Yeye's view, many ideal business models may encounter unexpected challenges in Latin America. "Take express delivery as an example. Mexican couriers seem to be caught in a logical loop, never telling you in advance when they will deliver or what time they will arrive. They always call you when they are at the door, and if you don't answer three calls, they just leave. But most people need to go out to work and can't stay at home waiting for the package. There are no delivery stations or lockers here. So now, when my package is about to arrive, I stay at home with my phone volume always on high to avoid missing the delivery call. I'm really depressed about it."

Instead of improving the delivery process or setting up lockers, the local solution is to build good relationships with couriers. "One day, a Mexican friend of mine bragged to me, 'Did you know? I've built a good relationship with the courier, and now I can even go to his house to pick up the package.'"

There is another challenge in express delivery in Latin America: the dense and closely packed slums. It's like a city within a city that operates in parallel with the outside world, with its unique logic and rules.

Misha Glenny, a British historian, described the dire security situation in Rio's slums in his book "Rio: The Story of a City in the Urban Jungle":

"In Rio, every ravine is a nation unto itself. Each slum in the city has a strong and distinct identity, which influences the socio-economic development of the drug trade and fundamentally explains why Rio experiences more and more unique violent incidents compared to Sao Paulo."

Street view of Sao Paulo, Brazil

Because of this, it is difficult for local logistics companies in Latin America to truly achieve "last-mile delivery" and can only leave packages at nearby post offices for residents to pick up themselves. This results in a low delivery success rate and frequent lost packages.

Regarding this situation, the head of J&T Express's Brazilian market told Xiaguang News that on the one hand, J&T Express's network layout in Rio is near the slums to ensure timeliness; on the other hand, the delivery drivers employed locally by J&T Express also come from the slums and are familiar with the internal social structure and operating rules of the slums. "If we follow the rules within the slums, there won't be too many problems."

Taxation is another pain point. As a federal country, Brazil's tax system is quite chaotic. For commercial express delivery, turnover taxes vary between different states and even different cities. On the one hand, the complexity of tax rates leads to fluctuating express delivery prices; on the other hand, interstate transportation faces tax inspections, with waiting times ranging from 4 to 14 hours, greatly affecting timeliness. If merchants evade taxes, express delivery companies also need to advance payment on behalf of merchants, affecting J&T Express's revenue.

In the view of Thomas, the founder of Bandalabs, an overseas influencer marketing company, the slowness in Latin America represents the solidity and stability of a company's moat. "If you establish certain barriers locally, the benefits will last longer. For example, in China, stores in Shenzhen malls change every few months; but when I went to Mexico in 2018, there was a bustling restaurant; now, that restaurant is still crowded. Isn't that a good thing for the restaurant?"

In 2020, Kwai invited Bandalabs to enter Latin America. Nowadays, Bandalabs has established a global online office system framework in China, Southeast Asia, North America, and Latin America. Thomas frankly stated that the most stable team is currently in Latin America.

"Latin Americans are actually very simple. Give them a relatively stable job and don't push them too hard, and they can do better. Moreover, they separate their life and work very clearly and don't bring too many emotions to work. This has two sides: on the one hand, Latin Americans can't work overtime day and night; on the other hand, they can maintain a balance on their own and won't be exhausted to the point of quitting due to high-pressure work like domestic employees," said Thomas.

Regarding the local management and communication of the team, Thomas found that Latin Americans do not try to read between the lines. "Just arrange what needs to be done directly, let them repeat 12345, and execute if there are no issues. Take it slowly and let them feel recognized and grow. Don't expect the rapid progress of the Chinese speed. Isn't it enough if they do better than other Latin Americans?"

In 1967, Latin American writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez created the magical realism masterpiece "One Hundred Years of Solitude," using a recurring time maze to metaphorically represent the sorrow of this land over the past hundred years. In fact, in the calendar of the indigenous Mayans in Latin America, time is conceived as a circular framework. Through the timeline of "rebirth," the Mayans can design a reunion point between themselves and their ancestors. Without the invasion of Western colonists, Latin American time would have forever belonged to the past, running counter to the modern, progressive, and developmentalist concept of time.

Today, the distinction between these two concepts of time still exists in this land. Chinese enterprises aspire to a rapid and unstoppable pace of development, which is bound to be frustrated in Latin America: workers here disappear after payday and wake up on park benches after a weekend binge, returning to work because they are broke; during an eight-hour workday, there are two Cafecitos—a relaxing moment or social activity to have a coffee, which can last one or two hours.

"But just because they are poor doesn't mean they are suffering." Yeye said, "What we Chinese consider poor families will still put a hammock in the living room, no matter how humble the home is; every Sunday is family day, and they will move tables outside to eat together. Their faces always show happiness, never suffering."

On Rio de Janeiro's beaches, a group of children are playing Altinha. This is a slum game that dates back to the mid-20th century. Children who can't afford a football and don't have an open field use homemade balls to play in narrow streets to improve their ball control and touch skills.

Even though it's slow, change is indeed happening. Sometimes, Marcus can clearly feel the reason and meaning behind his persistence. For example, once while taking a taxi, the driver, learning that he was from China, enthusiastically said, "Chinese people are great. You've invested a lot of money in Brazil, and the things you sell are good and cheap. Before the Chinese came, prices in Brazil were even higher."