The yen is playing the next master stroke

![]() 05/02 2024

05/02 2024

![]() 768

768

This is the 723rd original article published by the Xijing Research Institute and the 682nd original article by Dr. Zhao Jian.

At the end of March, I went to Tokyo to give a report, which coincided with Japan's economy experiencing several historical records: the Nikkei index hit a new high of 41,000 points, housing prices also returned to historical highs, recovering from the "lost three decades" in one fell swoop; prices bid farewell to decades of deflationary downturn and experienced inflation unseen in nearly half a century; the Bank of Japan also bid farewell to 17 years of interest rate cuts and nearly a decade of YCC, starting unprecedented interest rate hikes...

That day, I took a walk on the streets of Tokyo, looking at the dense crowds, and thinking about the major changes happening behind this calm daily life. Daily life dissipates the meaning of grand narratives. In fact, many so-called earth-shaking changes, when transmitted to individuals' daily lives, are temporarily just a small ripple, although they will continue to be impacted later. In the face of various historical records, although ordinary Japanese people have felt the pain caused by rising living costs, extremely low unemployment and a huge wealth effect have also brought significant welfare improvements and confidence to Japan. Overall, everything is still getting better.

However, there is one historical record that needs to be discussed separately, and that is the shocking depreciation of the yen. At that time, the exchange rate had fallen to a decades-low level of 150 yen per dollar. Many trading experts at the conference agreed that the yen would bottom out and rebound, and that the Bank of Japan would not let the yen fall below 150, so they recommended over-allocating the yen. However, the market specifically contradicted various linear extrapolations and trading predictions with a "fatal arrogance." The yen not only unexpectedly broke through 150, but continued to fall relentlessly after breaking 150,攻破各个支撑点位, until it reached 160. Finally, on April 29, it broke below 160, setting a historical record since 1990. Panic began to emerge, after all, the yen has functioned as a safe-haven currency for a long time. The yen's exchange rate depreciated so tragically that the Japanese stocks and houses that had barely risen in value were greatly discounted or even lost when converted into domestic currency. Investment experts who predicted a rebound in the yen on the forum therefore suffered significant losses, and investors who were originally confident in the Japanese economy and assets began to waver. Some even made assertions that Japan would experience a financial crisis.

However, soon after the yen exchange rate made a shocking turnaround, after breaking 160, it was violently pulled up by bulls by 500 points. It was like an ambush battle that lured the enemy into a trap, suddenly launching a counterattack to recover multiple lost territories. We can't help but ask, what is the Bank of Japan doing, what does it want to do, why adopt such a strategy, and create such large fluctuations? How will it operate in the future?

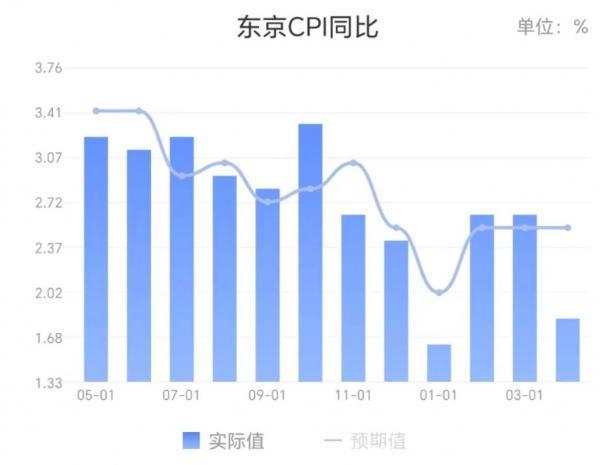

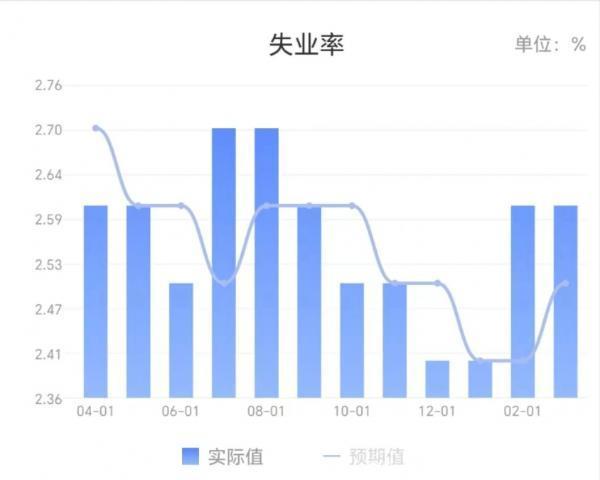

To understand the current strategy of the Bank of Japan, we must first understand the current situation facing the Japanese economy. Japan's current situation can be described as being caught in a crossroads of multiple economic and policy challenges. First, although it has finally emerged from decades of deflation and achieved inflation, due to the strong driving force of imported and cost-push inflation, income growth cannot keep up with prices, and people's sense of pain is still quite apparent. Fortunately, the employment situation is unprecedentedly strong, and the situation for young people is still improving. However, the latest data shows signs of falling inflation and economic weakness. Second, although asset prices have emerged from a long bear market, considering the marginal thrust of foreign capital, especially hot money, there are also significant risks hidden behind the new highs in asset prices. Once external funds withdraw, both the stock market and the real estate market will experience significant shocks. Third, the United States has unexpectedly experienced re-inflation, and the Federal Reserve has unexpectedly delayed interest rate cuts, continuing to expand the interest rate differential between Japan and the United States, with CARRY trades continuing to squeeze the value of the yen. Fourth, the international balance of payments structure has further distorted, with the primary income surplus mainly relying on overseas investment income, and most of this investment income has remained overseas without being repatriated for domestic consumption and investment to form GDP and employment.

It is worth mentioning Japan's overseas investments and the resulting unique international balance of payments structure. According to a recent report by Nikkei News, Japan's international balance of payments structure has undergone significant changes in recent years. Before 2010, Japan's current account had maintained a surplus due to its manufacturing advantages and strong global demand. After 2011, the trade deficit in the current account increased, and primary income such as interest and dividends from overseas investments became the core of the surplus. As a result, Japan has formed an international balance of payments structure that relies on investment profits rather than export profits. In recent years, there has been a tendency for overseas earnings not to flow back to Japan. According to statistics, Japan's primary income surplus in 2023 was 34.5 trillion yen, a record high. Among them, direct investment income such as dividends from overseas subsidiaries of Japanese companies was a surplus of 20.6 trillion yen, and reinvestment income accumulated as retained profits by overseas subsidiaries was 10.3 trillion yen. Half of these profits remained overseas and did not flow back to Japan.

So in summary, the current situation facing the yen is:

1. Inflation has returned, but the economy is beginning to weaken, likely entering a mini-stagflation cycle, with stagnation being a more concerning issue;

2. A large influx of foreign capital has pushed up asset prices, but given that the US dollar is not cutting interest rates, foreign capital is likely to flow out at any time, posing a risk of asset price collapse;

3. The interest rate differential between Japan and the United States continues to widen, and CARRY trades are likely to once again drain domestic liquidity, rendering domestic monetary policy ineffective;

4. A large amount of overseas investment income does not flow back to the country, earning GNP but not GDP. How to attract domestic capital to return and serve the local real economy is a policy option.

Faced with these four major challenges, choosing a significant depreciation of the exchange rate is indeed a master stroke, but it is also a risky move - any policy comes at a cost, and it is impossible to have everything. One only needs to choose the solution that maximizes benefits while minimizing costs based on the situation. The yen's choice of a "one-step" depreciation and subsequent rapid rebound at the 160 level is ingenious in:

1. Stimulating external demand and changing the distorted trade structure. On the one hand, it can stimulate commodity exports under the current account, making Japanese manufacturing more affordable and competitive in the current global environment of increasingly scarce demand; on the other hand, it can attract a large number of overseas tourists to consume and invest domestically - originally record-high housing and stock prices have once again become cheap due to the significant depreciation of the yen.

2. Blocking CARRY arbitrage trades based on the interest rate differential between Japan and the United States. According to the theory of interest rate parity, if there is an arbitrage space in the interest rates of the two countries, equilibrium must be achieved through hedging in the exchange rate in order to make the profits of CARRY trades zero and achieve a no-arbitrage equilibrium, otherwise capital will continue to flow in one direction. With a roughly 4% interest rate differential between Japan and the United States, if the yen appreciates by 4%, then an equilibrium in monetary assets will be achieved. How to make the yen appreciate by 4%? It is through an overshoot-style rapid depreciation. After depreciating to a certain level, the market unanimously believes that there is exchange rate overshoot (depreciation to the extreme and beyond), resulting in a reflexive expectation of appreciation, and this equilibrium is achieved, stopping the outflow of Japanese capital through CARRY trades.

3. The depreciation of the yen makes it worthwhile for overseas Japanese capital and retained profits to return home for consumption and investment. Overseas Japanese capital will experience a wave of repatriation under the stimulus of exchange rate depreciation, thus stimulating the domestic economy.

4. Locking in overseas capital that entered Japan to speculate on real estate and stocks in the previous stage (many are Chinese investors, as well as European and American investors like Warren Buffett). Their gains are locked in yen because once they try to sell yen assets and convert them into other currencies for repatriation, they will find that due to the significant depreciation of the yen, their investment returns have significantly decreased or even become losses.

It can be seen that for the yen, which is facing multiple "major changes," rapid depreciation is indeed a master stroke but also a risky move. Such a drastic depreciation is a huge drain on national credit. Fortunately, Japan has a fully marketized interest rate and exchange rate system and a developed financial system with complete capital mobility. Although the market creates fluctuations, it will also adjust spontaneously. The Bank of Japan has set a defense line at the 160 level, but it is not the last line of defense. In fact, no one can be sure, but for now, a psychological defense line has been formed. Therefore, in the broad depreciation zone from 120 to 160, the yen has indeed exchanged a larger policy space overall by sacrificing the exchange rate.

Does this have any implications for the Renminbi exchange rate, which is caught in a "triangular dilemma"? In the past two years, due to the duration and magnitude of the interest rate differential between China and the United States, both of which have set historical records, there has also been significant CARRY trading, causing domestic monetary policy easing to be absorbed by high-interest-rate dollars like a black hole, resulting in the strange situation of "the United States tightening monetary policy but experiencing inflation, while China loosening monetary policy but experiencing deflation." This is actually the siphon effect of dollar interest rate hikes. To change this situation, it is necessary to create a Renminbi appreciation expectation similar to the interest rate differential between China and the United States (around 3% annualized), otherwise people will continue to exchange Renminbi for dollars (or even borrow Renminbi at low interest rates to exchange for dollars), and then buy US dollar wealth management products with a stable return of 5%.

So how to change this imbalanced capital flow structure? There are essentially two methods: one is to increase the return on Renminbi assets, whether bonds, stocks, or real estate, to ensure a return rate of at least 5% (assuming a stable Renminbi exchange rate), so as to achieve marginal balance in asset selection compared to the return rate of dollar assets. The second is to increase the value of the Renminbi itself, that is, to raise expectations of Renminbi exchange rate appreciation. Drawing on the master stroke of the Bank of Japan, there is actually a lot of room for maneuver in the Renminbi exchange rate, especially under the pressure of deflation. Of course, in the context of negative returns from real estate, making the A-share market have a stable profit effect is also a good choice.