History should richly reward those 'early risers'.

![]() 11/14 2025

11/14 2025

![]() 565

565

At this year's Baidu World Conference, Baidu unveiled a series of innovative and leading AI applications, covering breakthroughs in large models, AI computing power, intelligent agents, AI search, digital humans, autonomous driving, and autonomous evolution. These showcased Baidu's underlying innovation capabilities driving the accelerated emergence of effective AI applications.

During the conference, Li Yanhong proposed the viewpoint of 'internalizing AI capabilities.' Baidu also demonstrated its phased achievements in internalizing AI with strength. The global progress of Luobo Kuaipao and the exceed expectations (unexpectedly strong) capabilities of Kunlun Core not only gradually revealed the harvest period of long-termism but also provided the outside world with a new perspective and opportunity to re-examine Baidu.

Can Baidu shed the label of being 'an early riser who missed the gathering?'

The phrase 'an early riser who missed the gathering' is a mockery in the tech industry towards companies that recognized important opportunities in a field early on but failed to reap the benefits or only did so much later.

There are indeed many such cases. IBM was one of the earliest to launch Watson Health, a rare large-scale early AI + health practice in the industry. However, it received a lukewarm response due to overly ambitious positioning. Nokia entered the smartphone operating system market earlier than Apple's launch of iOS, but its Maemo (not Meego) system failed to receive sufficient resources for development. Japanese automakers began researching electric vehicles more than 20 years before their Chinese counterparts but hesitated to develop them vigorously due to concerns about affecting fuel vehicle sales...

However, the focus here is not on these companies that failed to capitalize on opportunities correctly. Instead, we want to highlight companies that had the courage to stay ahead of their time but have not received proper recognition.

China is not lacking in companies capable of 'arriving late at the grand fair.' However, when it comes to 'rising early,' some people choose to remain oblivious. Therefore, I believe there is no need for justification. History will ultimately reward companies and entrepreneurs daring to 'rise early.'

——Introduction

In the lineage of Chinese internet companies, Baidu has always been a 'purely technical' force. It is not adept at sensationalism or performance but excels in exploring cutting-edge technologies that most people do not understand or cannot properly evaluate, often staying ahead of the curve.

Baidu has always been obsessed with technological innovation. However, precisely because of this habit, it is most vulnerable to being labeled as 'an early riser who missed the gathering.'

The concept of 'box computing' emerged early, but the technology to truly realize its vision only matured after 2023. Those unfamiliar with industrial history may not realize that Baidu had already started early in this track (track).

The Institute of Deep Learning and Baidu's U.S. Research Institute were early movers, but their harvest periods spanned decades. Many only saw them as cradles for nurturing talent in China's AI sector, unaware that Baidu's current AI empire is built on their foundations.

PaddlePaddle, Kunlun Core, and Luobo Kuaipao (Robotaxi) were all early movers. I could list many more such examples.

However, the notions of 'early' and 'late' are merely illusions in narrative, not the truth of history.

Among Chinese internet companies, Baidu may be the most unique. It resembles a Silicon Valley company, obsessed with technology and eager to bet on the 'future.' In some ways, it is even more committed to 'heavy models' than Silicon Valley companies. Yet, it seems to be the most deeply 'cursed' by the phrase 'an early riser who missed the gathering.'

This mockery seems somewhat reasonable.

When discussing 'rising early,' Baidu's track record almost perfectly annotates this phrase. From 'box computing' over a decade ago to the establishment of the Institute of Deep Learning (IDL) in 2013, and later Baidu's U.S. Research Institute, Apollo (Luobo Kuaipao) autonomous driving, self-developed Kunlun Core chips, and the earliest domestic deployment of the 'PaddlePaddle' deep learning framework... each initiative began when the C-end (consumer) market was still invisible, and even the B-end (business) market had not heard of them.

The so-called 'late gathering' refers to Baidu's turbulence in the mobile internet wave over the past decade and the delayed stock price 'catch-up' in AI commercialization returns. When the wave of large models finally swept in in 2023, and everyone rushed in, the 'market' truly became 'noisy.' This stark contrast between 'early' and 'late' seems to perfectly validate that schadenfreude-laden jest.

But is this really the case? Now that the noise of the 'late gathering' has finally arrived, should we not look back and re-examine the value of 'rising early?'

History and public opinion often toy with our insight, with three common scenarios.

The most typical is mistaking the 'widespread emergence of C-end popularity' as the 'moment of value birth.'

Indeed, fireworks look best at the moment of ignition, but they cannot happen without inventing fuses and gunpowder.

Take the third wave of artificial intelligence that we are familiar with. Ninety percent of people I know believe that its landmark event was AlphaGO's victory over human chess players in 2016.

The media enjoys narrative rhythm, but technological implementation requires solid foundations—algorithm scalability, data governance, computing power structure, industry know-how, risk control compliance, cost management, and grayscale deployment. Any unaddressed link among these dozen aspects can hinder the commercial closed loop (closed loop).

Baidu was the earliest riser, entering the field in 2010. However, the true arrival of AI scalability returns for Baidu, such as the explosion of commercially viable businesses like intelligent cloud, self-developed AI chips, digital humans, generative AI large models, and widespread autonomous driving deployment, only occurred in the past two years, nearly a decade after that 'landmark event.'

The value of technology is never born at the moment it tops Weibo's hot search but at the moment 'engineering turns mysticism into reality.'

Another scenario is judging the 'catching up with the gathering' standard solely by profit statements while ignoring the 'systemic assets' behind the balance sheet.

Baidu not only started early in AI R&D but also invested hundreds of billions in R&D during the first decade without massive returns. From a financial statement perspective, this seems terrible.

However, can R&D capabilities, standard construction, operating system-level frameworks, and underlying self-developed chips be reflected in a liability statement?

Should we not ask whether we have overlooked the decisive value of establishing standards, developing underlying technologies, and building systems while only focusing on short-term profit and loss statements?

Can we answer—when everyone talks about model applications, who is building the 'thankless' industrial-grade deep learning framework? When most are 'assembling' intelligent driving solutions, who is burning money to develop L4 autonomous driving?

Do we realize that technology companies are not sales-driven enterprises. Although they need sales to reflect in reports, their ultimate moat is not merely profit data but a genuine ecological niche moat?

The construction of an ecological niche cannot be simply assessed by sales volume and cost. It concerns a company's voice in the ecosystem, the definition rights of the industrial chain, and whether developers can happily and smoothly create intelligent agents using it. It also concerns whether thousands of industries can smoothly solve AI implementation challenges. Moreover, even if you only look at it from a revenue perspective, I can tell you—in the technology world, short-term profits are 'cash,' while ecological niches are the 'right to mint currency.'

Analyzing these three questions may prompt us to view 'early risers' from a different angle.

If we consider the rise of the first batch of privately colored IT enterprises in the 1980s as the starting point, the development of China's digital industry has spanned over 40 years. In these 40 years, we have learned to 'bring in' and mastered 'model innovation.' However, when did we truly dare to 'innovate and lead' in core technologies?

The answer is: quite late.

We need not avoid the pain points of 'rising late.' When we look around, almost all areas 'constrained by others' are due to our missed historical opportunities to 'rise early.' Of course, some misses were caused by the times, not corporate responsibility.

When Huawei resolutely launched 'Pure Blood HarmonyOS,' it aimed to make up for decades of lagging and following in operating systems. Why is it so difficult? Because the barrier of an operating system is never code but ecology. It is the millions of developers already accustomed to Android and iOS development paradigms and the hundreds of billions of lines of 'legacy code' already precipitate (deposited) on old platforms.

When the entire semiconductor industry is 'catching up' and purchasing mature process equipment at high prices, we are paying hefty 'tuition fees' for the absence of underlying ecological niches in system-level chips. As for industrial software (such as CAD, EDA), high-end storage, flash memory particles... in these areas, we were not 'unaware' but found the international market already highly mature when we realized the need to address shortcomings.

Why is the cost of 'being late' so heavy?

Because the barriers in technology-intensive markets are never a single invention. They are not a flash of inspiration like Newton being hit by an apple. They are a 'net' woven from countless patents and an ecology built by massive developers and partners.

As stated in Thomas Samuel Kuhn's 'The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,' 'innovation' in today's tech era increasingly manifests not as the individual labor of a genius scientist but as the result of a series of organized, systemic innovations.

Sufficiently complex, it must be sufficiently early.

Early enough to define interfaces, early enough to build organizational structures, early enough to establish patent walls, and early enough to develop ecological barriers. These four elements are the true keys to ensuring sustained access to technological dividends.

From this perspective, we can better understand the strategic necessity of Baidu's 'early rise.'

Let us add some 'granularity.'

Take PaddlePaddle as an example. In the AI era, deep learning frameworks are the 'operating systems.' If large models are the 'engines,' frameworks are the design blueprints and manufacturing lines for those engines. When Google's TensorFlow and Meta's PyTorch were conquering the globe, if China lacked its own 'foundation,' it would be equivalent to building the 'foundation' of the entire future intelligent industry on others' land.

This would mean all our AI applications would 'parasitize' on others' standards. Once standards change, interfaces are 'poisoned,' or supplies are cut off, our 'AI edifice' would instantly become a 'ruined building.'

The value of PaddlePaddle lies not in bearing the title of 'one of the global three major frameworks' but in being an 'engineering-oriented mass toolchain platform.' Within Baidu's internal business flows of advertising ranking, search relevance, speech recognition, image and video, and recommendation systems—where 'internal battles are fierce'—PaddlePaddle first serves as a platform to navigate pitfalls internally before paving the way externally. A mature open-source framework must be a stabilizer across the entire chain, from data reading, feature governance, model development, distributed training, deployment inference, to monitoring and rollback.

More importantly, PaddlePaddle chose open source—a 'niche choice' with far-reaching significance beyond mere 'technical choice.' Open source means relinquishing part of 'technical control' to the community in exchange for broader 'collaborative control.' It transforms Baidu's capabilities into the industry's collective strength. This is not charity but compound interest—the larger the ecology, the more stable the tool; the more stable the tool, the larger the ecology. What the platform gains is platform dividends, not single-point profits.

However, this seemed extremely anti-commercial in the early stages—burning money without earning profits and 'gifting' results to others. But this is the fate of early risers like Baidu: you must spend unprofitable decades to secure a profitable future for the entire industry.

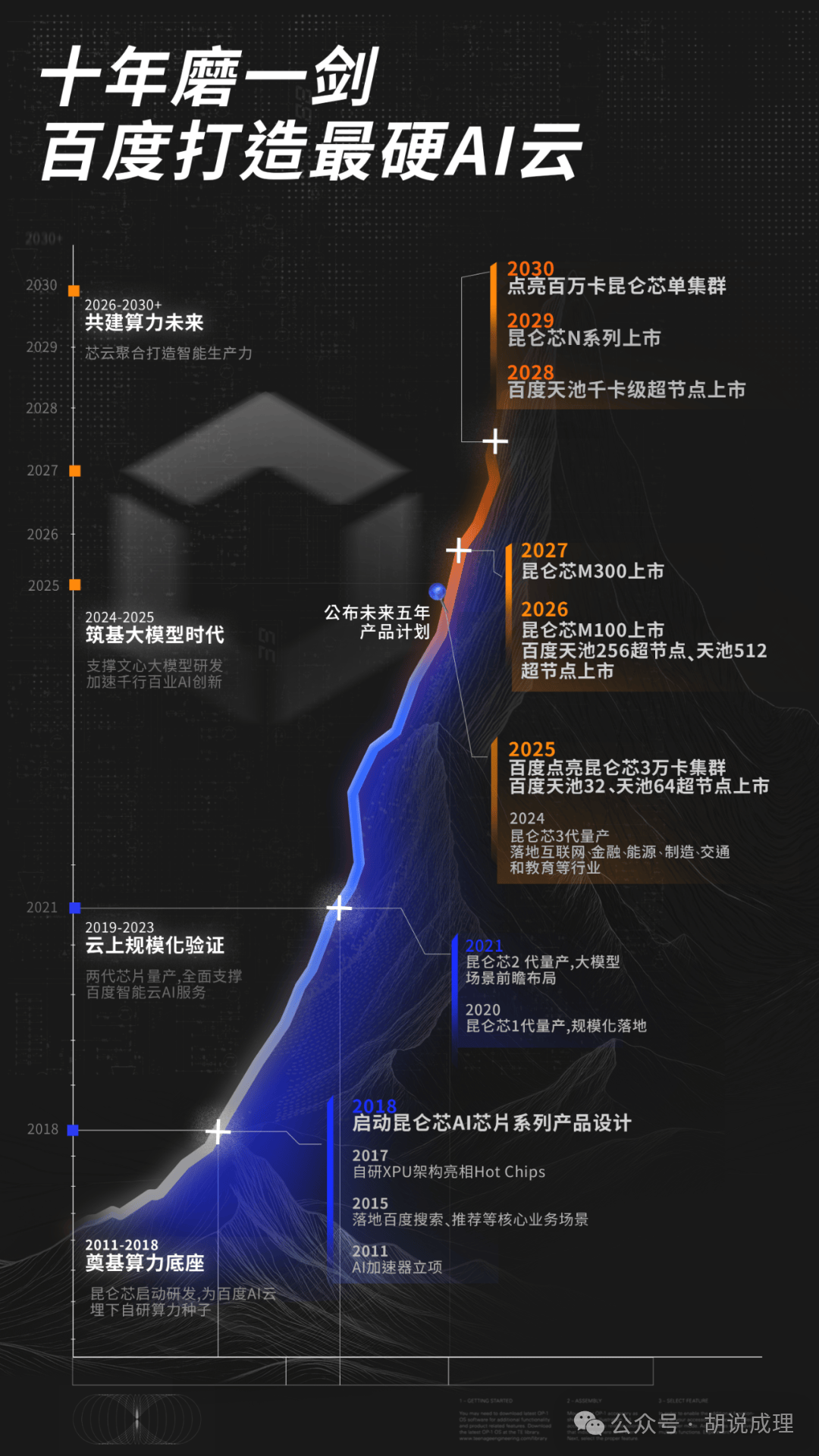

Now, consider Kunlun Core. When AI computing power became a bottleneck for the entire industry (including Baidu itself), if Baidu had not started researching AI accelerators based on FPGAs (Field-Programmable Gate Arrays) as early as 2011, it would not have the self-sufficiency in AI computing power enabled by thirty thousand Kunlun Core chips today.

But what era was that? It was when the mobile internet was just starting, and everyone talked about the 'Thousand-Group War' and 'APP factories.' Back then, no one was building mature process chips, let alone AI chips. It was truly early.

But why did Baidu embark on this lonely path?

Because Baidu realized earliest that the endgame of AI is computing power, and the future of search (Baidu's core business) would be AI-driven. Li Yanhong and his colleagues touched the 'computing power wall' earlier than others but were not understood.

Even when the first-generation Kunlun Core entered tape-out in 2018, many did not understand why Baidu would 'reinvent the wheel' when NVIDIA's GPUs were available, believing Baidu was hyping it up.

Computing power is not just TFLOPS on paper but latency budgets, thermal design power, memory bandwidth, and interconnection topologies in real-world conditions. Kunlun Core does not bet on the success of a single blockbuster AI accelerator chip but seeks Computing power security (computing power security) when all four layers of the architecture are complete.

Only with computing power security can there be further 'end-cloud collaboration' for computing power sinking and ascent: balancing inference costs, throughput, and energy efficiency in the cloud; and stably supporting low-latency necessities like speech, image, and data analysis at the edge.

Today, when large models have ignited a computing power crisis and 'latecomers' wield checks but cannot buy high-end GPUs, Baidu has truly reaped the rewards of its 'early rise.' It possesses the confidence of 'computing power autonomy' and the end-to-end optimization capabilities of a 'model-framework-chip-application' four-layer integration.

Finally, consider Luobo Kuaipao (Robotaxi). If 'car manufacturing' is the 'late gathering,' then what Baidu started in 2013 was autonomous driving, much earlier. It chose the most difficult and heavy L4-level route—another 'anti-commercial' decision. L2+++ (high-level intelligent assisted driving) is clearly easier to implement and monetize faster. Why pursue L4?

Because 'early risers' like Li Yanhong focus not on next year's financial reports but on the endgame and new beginnings a decade later. In his book 'Intelligent Transportation,' Li Yanhong proposed that the endgame from intelligent assisted driving to autonomous driving and the future of human transportation must be a self-operating network of 'autonomous driving,' not merely selling better cars. Therefore, Baidu must rise early to accumulate the massive 'Corner Cases' (extreme scenarios) required for L4, which L2 cannot match. It must run, test, learn, and feedback on real urban roads over millions of kilometers at substantial cost.

This is the true underlying logic of 'getting up early': it's not about striking a pose, compiling data that investors love to see, or telling stories that consumers enjoy hearing. Instead, it's a collection of 'heavy decisions' that, at the time, seem 'unreasonable,' 'uneconomical,' and 'counter to consensus,' yet point towards the ultimate outcome.

From this perspective, there weren't too many, but rather too few, pioneers who 'got up early' for China's digital technology industry. Sadly, when the true early risers set out with the morning glow, they often find themselves alone.

Was it because he truly rose too early, leaving him shivering in the cold at the top? Or were there too many 'pretending-to-sleep' peers around him?

Looking across China's digital industry, we can easily spot a strange phenomenon—

In the 'deep waters' of pioneering exploration, with huge investments and uncertain returns, there are often few responders, and even not lacking in cold stares and ridicule. However, as soon as the technological path is validated over the weekend, and the business model shows promise, a swarm of companies rushes in, and a group of founders emerge, all-in on something—announcing investments of billions or even hundreds of billions to venture into new fields. The cash reserves on their books are far more substantial than Baidu's.

Did they really oversleep?

I'd like to offer my conjecture—the vast majority did not; they were merely 'pretending to sleep.'

This is no longer Newton's era. Information is highly transparent, and the internet is omnipresent. No one can keep their research and development 'absolutely secret.' Those pretending to sleep are well aware of what others are doing; they may even have seen the trends earlier than anyone else. Yet, they prefer to let others complete the toughest '0-1' exploration, allowing the 'early risers' to brave the mines, make mistakes, and educate the market.

They are like a group of 'gold prospectors' waiting outside the oil field. They don't take responsibility for exploration, drilling, or laying pipelines. They only wait for the 'early risers' to bring out the first barrel of crude oil, then they swarm in, scrambling for the 'high-quality crude' that spills over at the 'late market,' or even buying up the entire oil field.

They choose to enter rapidly at the '1-10' stage, leveraging their capital and traffic advantages to 'pick the fruits.'

This exquisite form of egoism represents the industry's greatest internal friction.

What's even more ironic is that when they arrive at the 'late market,' instead of feeling grateful for the 'early risers'' pioneering efforts, they turn around and mock the pioneer who 'got up early,' ridiculing him for being 'too slow' or 'missing the window of opportunity (window of opportunity).'

If this twisted value ethos, which glorifies 'fruit-picking,' becomes mainstream, we will never witness true innovation-led progress.

A soil that only produces 'late-market speculators' cannot nurture towering 'centennial enterprises.' Moreover, the ones waiting outside the oil field are not just domestic 'jackals'; there are also international 'hyenas' who have been playing this game for centuries.

Ultimately, the history of technology and industry is fair. It may seem to toy with the 'early risers,' but over a longer timeframe, it will undoubtedly reward those who 'rise early and persevere.'

This 'reward' is not a simple linear return but manifests in the form of 'compound interest,' layering up over the long years. We can break it down into a 'triple compound interest mechanism':

Firstly, any complex technology has an iron triangle of 'cost-quality-reliability.' Being an early riser means starting to climb this steep learning curve the earliest. They use more time to trial, iterate, and optimize.

While latecomers are still struggling to reach the 'passing grade' of 60, early risers have already reduced unit costs to a lower level while elevating reliability to a higher standard. In the field of autonomous driving (such as Baidu's Apollo Go), this is reflected in massive real-world road test data and more mature safety models; in the chip sector (such as Kunlun Core), it is evident in superior power efficiency ratios and more stable mass production yields.

It's not just limited to the IT industry; let's look at other sectors—here's a prime example: BYD and Tesla.

Around 2015, both companies faced ridicule for 'getting up early.' Tesla was mocked by traditional automakers for 'chaotic supply chain management' and 'quality control disasters'; BYD was derided as 'cheap' and 'technologically backward.' However, what the outside world failed to see was that each had 'risen early' to climb two different yet equally steep learning curves: Tesla climbed the manufacturing curve of software-defined vehicles and integrated die-casting; BYD climbed the battery technology and vertically integrated supply chain curve.

They paid exorbitant tuition fees for getting up early over a decade. When the 'late market' for new energy arrived, traditional giants like Toyota and Volkswagen, who had been 'pretending to sleep,' suddenly realized that their 'learning curves' accumulated over a century in internal combustion engines had become nearly obsolete.

Today, latecomers can use money to buy packaged intelligent software and hardware, but they cannot buy the rapid dimensional upgrading capability in intelligent driving heritage; they can use money to buy talent, but they cannot buy the massive feedback data that only terminal-scale deployment can bring... You can even use money to buy time, but you can no longer buy the right timing.

The reason to get up early is when you are already prepared when the opportunity arises, or even when you create the opportunity yourself. At that point, every step you take early on will, in the future, become an insurmountable gap for your competitors.

Secondly, and more importantly, intervening during the 'wild west' period of the industry means you have the best chance to become the 'rule setter.'

ASML is the ultimate embodiment of this logic. It wasn't the first to build photolithography machines, but it 'got up early' to forge an alliance. It firmly bound Germany's Zeiss (lenses), the United States' Cymer (light sources), and its own unparalleled electromechanical technology to its chariot through capital and contracts. As a result, ASML defined not only the technical standards for EUV photolithography machines but also a 'you-in-me, me-in-you' 'industrial alliance standard.'

When 'late market' challengers seek to enter, they find themselves not just facing an ASML but the entire planet's top-tier ecosystem of optics, materials science, and precision instrumentation.

Finally, timing is merely a temporal concept; firmly holding onto one's ecological niche in development is the ultimate form of compound interest.

Baidu has consistently invested in underlying technologies like 'PaddlePaddle' and chips for a decade, repeatedly advocating for AI implementation and promoting awareness of AI applications domestically. What it competes for is not just its own temporal compound interest but also that of China's AI industry—today, everyone knows we have only one rival on the path to becoming the global epicenter of AI innovation. However, if your ecosystem lacks millions of developers, hasn't generated millions of enterprise models, can't develop tens of thousands of intelligent agents with low barriers, and doesn't have tens of millions of autonomous driving vehicles, you cannot secure this ecological niche.

Baidu's early rise is not just for itself but also for the nation.

Today, when we examine Baidu's top ten inventions, we find that inventions in underlying technologies still account for at least the majority. This is precisely Baidu's logic in developing AI. Whether it's AI Cloud or the ERNIE large model, its strategic intent is to become 'infrastructure.' It has a complete ecosystem but does not seek to personally enter every vertical field; instead, it empowers various industries through 'open-source' and 'openness.' What it aims to be is the 'ecological niche,' not the 'blockbuster single product.'

Due to space constraints, we cannot provide more examples. However, I believe I have outlined a clear trajectory that confirms the strategic resolve of an 'early riser' and his forward-looking judgment of the 'endgame.' From NVIDIA to Huawei, from BYD to OpenAI, every giant that has traversed cycles has repeatedly told the simple truth that 'early risers will be richly rewarded.'

History is generous; it rewards the 'early risers.' But history is also cruel; it only rewards those who 'rise early and persevere.'

Baidu's 'getting up early' is not a blind accumulation of technology but a well-considered 'long-termism' approach. It has several distinct characteristics worthy of deep contemplation by all 'technology-driven enterprises':

—It's a strategic choice of 'ecosystem and platformization.' It understands that in the AI era, no single company can do everything. The true 'moat' is not a 'closed-source' proprietary technique but ecosystem prosperity. It chooses to be the 'ecosystem control point,' using openness to aggregate developers and partners.

—It's about patiently managing capital and building organizational resilience. I believe that within Baidu, many AI projects have 'ten-year ledgers.' This means management has a 'patience' that transcends short-term (or even mid-term) financial report fluctuations for these frontier explorations. Only with this patience, coupled with strong organizational resilience and periodic review mechanisms, can the immense uncertainty that comes with 'getting up early' be offset.

—Most importantly, it's about the founder always remaining at the helm while possessing the wisdom to 'reversibly trial and error and switch routes' at any time—getting up early does not mean 'sticking to one path until death.' Those who walk must be strategically resolute but tactically agile, maintaining the ability to quickly trial and error, tolerate failure, reconstruct the organization, and make enterprise-level decisions to ensure they do not 'sink' too long on the wrong path.

These three points collectively form the spiritual essence of Baidu's 'early rise.' Are they not also a scientific spirit that transcends opportunism, which technology enterprises in our era should possess—daring to bet before consensus forms, daring to maintain resolve amidst noise, and daring to pursue underlying innovation regardless of temporary praise or blame?

I suddenly recall why Li Yanhong transitioned from his early love of music and dance to becoming a middle-aged enthusiast of gardening—for an introverted founder who always retains the 'essence of a technologist,' he should be more like a botanist or gardening aficionado because plant growth is slow, and the wait from sowing to harvest is long. Those who love gardening believe in the accumulation of 'slowness,' the power of 'soil,' and the importance of 'ecological' accumulation. Just as he would insist on drinking a sobering cup of Chinese tea from Beijing after the noise of a celebration banquet.

Today, as the 'late market' for AI finally becomes bustling, we should pay greater tribute to those 'early risers' who blazed the trail.

Because they were not just betting on their own commercial empires but also paving the way for the future of the entire industry. Their 'early rise' has given us the confidence not to be at the mercy of others in today's 'late market.'

I can't help but think of Baidu's advocacy for 'AI internalization.' To some extent, this means using its mature businesses and organizations as experimental grounds for AI.

When I see this, the first things that come to mind are Wilhelm Röntgen, the inventor of X-rays, who took the first X-ray image in human history, of his wife Anna Bertha's hand, to verify that the rays could penetrate flesh; and Edward Jenner, the pioneer of smallpox vaccination, who conducted his early series of experiments on effectiveness and safety on several children, including his own son... So, when we talk about this term, shouldn't we show more respect for the spirit of those early risers?

History should and is rewarding them. At the very least, we should offer understanding and applause when they set out again in the darkness before dawn, rather than delivering cheap mockery like 'got up early, but arrived late' as they trudge forward.

Now, as more and more enterprises awaken in the era of large-scale AI applications, Li Yanhong has further proposed the goal of internalizing AI capabilities within enterprises—in my view, this marks a significant departure from the past. It regards AI as a systemic capability, an internal strength, of enterprises. I believe more and more companies will recognize this viewpoint and, along this dimension, join Baidu in enjoying the dividends of the era.