Is 'Refund Only' a detour in e-commerce history?

![]() 08/30 2024

08/30 2024

![]() 495

495

In 2021, Pinduoduo pioneered the "Refund Only" policy in China, allowing users to receive refunds without returning the products, aiming to protect consumer rights, filter out quality merchants, and foster a healthy platform ecosystem.

However, during implementation, the policy gradually distorted, and even gave rise to professional 'wool-gatherers' who made money by teaching others how to request refunds. Numerous merchants were driven to desperation, culminating in the 'store bombing' incident in March 2023. Pinduoduo made no policy adjustments in response.

As Pinduoduo expanded its market share, "Refund Only" became an industry standard. By January this year, Douyin, Taobao, JD.com, and Kuaishou had all introduced similar policies.

Yet, just eight months after its launch, Taobao was the first to backtrack, loosening the "Refund Only" restrictions. By setting experience thresholds, opening complaint channels, and strengthening intelligent risk control, it aimed to safeguard the rights of both buyers and sellers.

We wonder: Is the controversial "Refund Only" policy indeed a detour in e-commerce history?

Author | Akong

Editor | Haoran

This is an original article by Shangyin Club. Please contact us for reprints.

01

How did 'Refund Only' originate?

Financial writer Wu Xiaobo has been significantly impacted by the "Refund Only" policy.

His first purchase on Pinduoduo was his own book "Turbulent Decades," priced at 21.15 yuan for three volumes (compared to 112 yuan on Dangdang). Upon receiving a pirated copy, he successfully requested a refund within two days. Wu Xiaobo praised the service as "excellent and seamless."

Pinduoduo then recommended his book "The Story of Moutai," priced at just 15.4 yuan, even though the legitimate version, priced at 88 yuan, hadn't even been printed yet.

Wu Xiaobo lamented that "Refund Only" was a nightmare, potentially devastating the industry. However, his pleas failed to resonate with readers, with a majority voting in favor of the policy in a poll he conducted.

Poll initiated by Wu Xiaobo Channel

In fact, "Refund Only" is not unique to Pinduoduo; Amazon pioneered the policy in October 2017, persuading sellers that it could "save return shipping costs and processing expenses, reduce dissatisfaction rates, and improve ratings."

For Amazon, this policy aimed to alleviate customer concerns and incentivize purchases. A survey revealed that 36% of global consumers said free returns encouraged their shopping decisions, while over 55% admitted abandoning purchases due to inconvenient return options.

Tracing back further, American retail giant Costco's return policy is legendary: half-eaten food, dried-out Christmas trees, even years-old clothing – all accepted.

Costco Return Policy

China's Pang Donglai rivals Costco in this regard. With slogans like "Unsatisfied? Return it!" visible everywhere, one netizen shared that they received a full refund for a disappointing bowl of beef noodles and even received an extra box after complaining about moldy cherry tomatoes at the bottom of a package.

Their rationale: retain customers and boost repeat purchases. Costco's seemingly loss-making return policy yields a 90% membership renewal rate, free marketing exposure, and powerful word-of-mouth advertising.

From a customer acquisition cost perspective, retaining existing customers is five times cheaper than acquiring new ones. According to Ernst & Young, long-term loyal customers spend 1.7 times more on average than regular customers. A Bain & Company study found that a 5% increase in customer retention in the US could boost profits by 25% to 95%.

So, why are offline retailers' "Refund Only" policies well-received, while e-commerce versions are criticized? The key lies in who bears the cost: offline retailers absorb it, while e-commerce platforms shift it entirely to sellers, earning customer goodwill without incurring expenses.

02

How did 'Refund Only' go astray?

Initially, Pinduoduo's "Refund Only" policy aimed to combat counterfeit sellers.

Early on, Pinduoduo struggled with counterfeit products like pirated books, fake Moutai, knock-off electronics, and phones. Critics lambasted the platform for regressing China's anti-counterfeiting efforts by 20 years. Pinduoduo countered that counterfeiting was a societal issue, not solely its responsibility.

Cracking down on counterfeits has long been a challenge for e-commerce. Before Pinduoduo, Taobao also grappled with counterfeit issues. Liu Qiangdong even accused Taobao of being China's largest source of fakes, while Jack Ma declared counterfeiting a "cancer" Taobao must conquer.

After going public, Taobao actively combated counterfeits, making it harder for low-quality, low-priced goods to gain exposure. It later established Tmall to attract big brands, offering preferential traffic.

This shift was costly for Taobao. In October 2011, Tmall's predecessor, Taobao Mall, raised service fees and deposits, triggering protests from hundreds of merchants outside Alibaba's headquarters. Over 2,000 products were delisted in the "Siege of October" incident, which ended with Jack Ma halving the new fees to appease merchants.

In an interview, Huang Zheng said, "Knock-offs aren't counterfeits. We won't use the Tmall model to combat fakes; it wouldn't work for us. We might die trying."

In 2015, Taobao expelled 240,000 low-end sellers, many of whom joined Pinduoduo, accelerating its growth. Huang Zheng argued that adopting the Tmall model would be suicidal for Pinduoduo.

However, these sellers' counterfeit goods plagued Pinduoduo. Initially, it froze their funds upon detecting fakes. Merchants resorted to protests, including bringing children or pregnant women to the office, and even stalking employees, including Huang Zheng himself.

In 2021, Pinduoduo devised the "Refund Only" solution, initially applied to perishables to avoid high return costs and inventory buildup. It later proved effective against counterfeits, punishing sellers and deterring resales.

As the policy expanded, even expensive items like 1,400-yuan wall-mounted washing machines were refunded without returns due to installation issues. Even authentic products with quality inspection reports faced refunds.

Pinduoduo tolerated obvious 'wool-gathering' behavior, spawning 'wool-gatherers' who profited by teaching others how to request refunds and navigate customer service. Merchants were enraged by the platform's bias, leading to the "store bombing" incident.

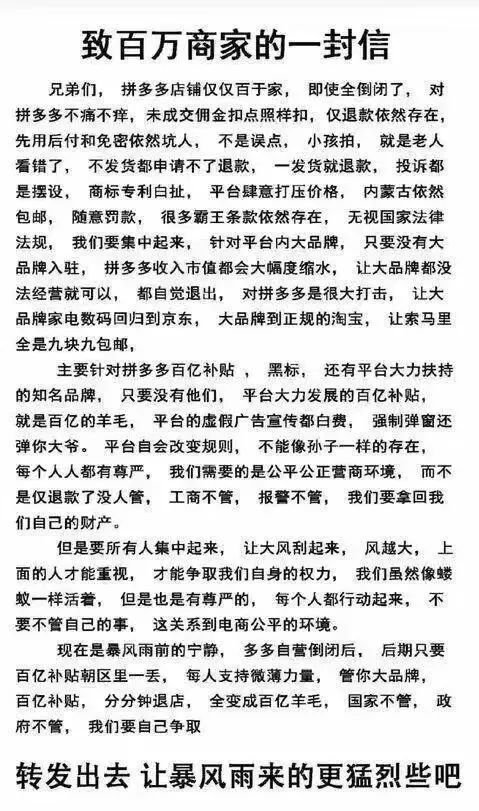

On March 25, 2023, Pinduoduo launched its self-operated store "Duoduo Welfare Society," which was forced to close within four hours due to malicious orders and refund requests from angry merchants.

A letter circulating online criticized Pinduoduo's unfair terms, urging merchants to unite and reclaim their rights, fostering a fairer e-commerce environment.

Pinduoduo ignored the backlash, knowing that despite refund losses, small and medium merchants remained dependent on the platform for profits. Pinduoduo had already shed its counterfeit image through subsidies and forged deeper ties with brands and distributors, becoming China's most valuable e-commerce company.

03

Is 'Refund Only' a detour in e-commerce history?

Ultimately, the emergence and controversy surrounding "Refund Only" stem from a trust misalignment among merchants, platforms, and consumers.

Trust is a vital lubricant for social systems, simplifying complexity. German sociologist Niklas Luhmann argued that trust simplifies complex relationships into binary states (trust vs. distrust), facilitating swift decisions.

Throughout history, humans have relied on kinship, religion, and law to establish trust. Trust's foundation is reputation, intertwined with market economics for millennia. Both buyers and sellers rely on reputation, which determines trustworthiness and incentivizes trustworthy behavior. However, human cognitive limitations limit our understanding of reputations to a few hundred entities, restricting transaction scopes.

E-commerce vastly expands these scopes. Economists envisioned an ideal market of anonymous buyers and sellers seamlessly transacting in a frictionless environment, with early e-commerce platforms seen as exemplars.

Yet, platforms soon realized this vision's impracticality: both buyers and sellers had incentives and opportunities to deceive. As transactions grew complex, fraud and misrepresentation risks multiplied.

E-commerce platforms adapted ancient reputation systems, introducing third-party escrow services. Consumers evaluate merchants, and platforms rate stores for user filtering. Platforms hold funds during transactions to assuage consumer doubts.

However, reviews can be faked, and ratings bought. Taobao and Pinduoduo even hide negative reviews, showing select labels instead. With more merchants offering incentives for positive reviews, consumers struggle to find genuine opinions.

Almost entirely positive reviews on Taobao

Consumer trust in platforms and merchants plummeted. E-commerce platforms introduced policies like buy-now-pay-later, fake-one-pay-ten, and seven-day no-reason returns to regain trust, including "Refund Only."

While swiftly appeasing consumers, "Refund Only" shifts platform responsibilities to merchants. Abused by opportunistic consumers, it fosters merchant distrust towards platforms and consumers.

Game theory suggests trust can persist through repeated interactions, reinforced by long-term impacts. Merchants hope for repeated interactions with platforms, while platforms seek the same with consumers, creating an imbalance favoring consumers over merchants.

Blindly following suit, Douyin, Taobao, JD.com, and Kuaishou introduced "Refund Only," exacerbating this imbalance. With few counterfeit concerns among their predominantly brand-focused merchants, these policies offer limited user benefits.

Platforms can intervene, as Taobao demonstrates by delegating more refund decisions to high-performing merchants, rejecting suspicious refund requests, and manually reviewing high-value refunds. Inaction reflects a reluctance to incur costs, favoring a free ride.

Without intervention and well-designed rules, individual calculus prevails. In a trust-deficient system, each party assumes the other will exploit opportunities for deceit, prompting defensive strategies and escalating negative interactions.

Conflicts over "Refund Only" escalate, with over 160,000 complaints on Heimao Platform and over 1,400 related court cases. Media reports tell of merchants traveling long distances to confront buyers over 9.9-yuan T-shirt refunds or being sued by sellers over 11-yuan clothing refunds, later settling for 800 yuan in legal costs.

To offset losses, merchants raise prices, embedding "Refund Only" costs into consumer bills. Consumers face higher time costs seeking quality products amidst a speculative market prone to both genuine and counterfeit goods.

Such an environment is exhausting, risky, and costly for platforms, fostering frequent conflicts. Thus, "Refund Only" suits specific scenarios and categories. Without intervention or biased favoritism, trust gaps will exact costs from all parties.

References:

1. Trust: Interpersonal Ties in Economics, published by China Science and Technology Press

2. Trust: Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity, published by Guangxi Normal University Press

3. Counterintuitive Pinduoduo, by Xinghai Intelligence Bureau

4. How Many People is Pinduoduo's 'Refund Only' Policy Angering?, by Chabei

5. The Story Behind Huang Zheng and Pinduoduo's 'Refund Only' Policy, by New Business School

6. Who Does 'Refund Only' Anger?, by Dingjiao One

7. The Sorrow of 'Refund Only' Policies on Pinduoduo, Douyin, Taobao, and JD.com, by Xinshang

8. Merchants Driven Mad Sue Over 4,000 'Wool-Gatherers' Disrupting Market Order, by Xinzhoukan

Welcome to discuss with the author!