Accumulated Protection for 100 Billion Times! Why Do Telemarketing Calls Persist Despite Robust Operator Safeguards?

![]() 07/03 2025

07/03 2025

![]() 715

715

Spam calls cannot be ignored; they must be stopped.

Have any of you ever received telemarketing calls?

Recently, as my car insurance was about to expire, I received daily calls from insurance salespeople from various companies for an entire month. Sometimes, one sales call barely ended before another from a different salesperson from the same insurance company would come in. Besides insurance, telemarketing harassment—or spam calls—is also rampant in real estate, education and training, securities, medical care, and other fields. For instance, a foreign securities company kept calling me for an entire year, inviting me to open an account.

Even with various anti-spam apps installed and the mobile phone system's built-in blocking function enabled, unsolicited calls continue unabated. Repeatedly hanging up and identifying calls has become a daily routine for many mobile phone users.

On the user side, spam calls have seriously disrupted everyone's daily communications; on the industry side, the prevalence of spam calls is alarming. In June 2025, the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT) announced that the "Do Not Disturb for Incoming Calls and Messages" service it spearheaded had provided 101.37 billion services to 1.06 billion users nationwide by the end of May.

Image source: Leitech

That's right, it's not just apps like Mobile Manager that intercept spam calls and messages. As early as 2019, the three major operators—China Telecom, China Mobile, and China Unicom—joined forces with the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT) to establish an anti-spam call protection system at the operator level. In 2024, this system added a do-not-disturb feature for text messages and was integrated into the current "Do Not Disturb for Incoming Calls and Messages" service.

So, how does this operator-level communication protection differ from the anti-spam protection that comes with mobile phones?

The difference lies in "front-end blocking" versus "end-blocking".

Compared to the protection functions offered by mobile phone manufacturers or apps, the anti-spam service led by operators differs most significantly in the level of blocking. Put simply: Operators have a higher level of blocking, capable of identifying, marking, and blocking calls before they reach the user's mobile phone, which falls under "pre-protection"; whereas mobile phone-end protection involves comparing incoming call numbers with the blocking database after the phone receives notification from the base station, reminding users whether to answer or directly hiding the call, which falls under "end-recognition".

In essence, mobile phone blocking silences or hangs up spam calls, or lets the phone's AI assistant "answer on behalf"; with operator protection enabled, however, the caller cannot even connect to your number.

Furthermore, since the operator's pre-blocking is effective at the operator level, this spam blocking system can directly identify call attributes based on the communication characteristics of the caller, utilizing AI to recognize the caller's phone characteristics or industry information, without the need for multiple user reports.

Image source: Leitech

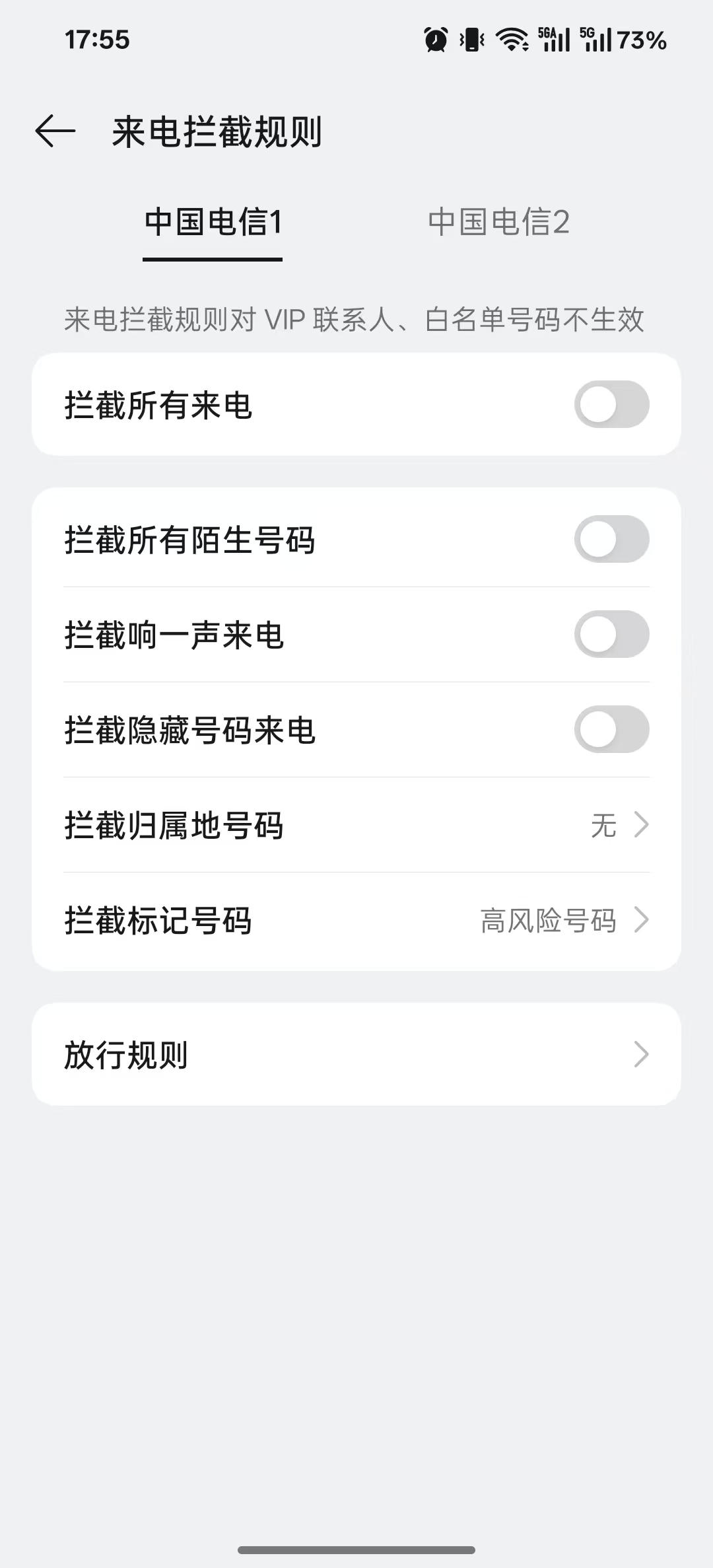

And because the relevant services are effective on the operator side, users do not need to install any apps. They can directly enable the service through the relevant official accounts (China Mobile - China Mobile High-Frequency Spam Call Protection; China Unicom - Unicom Assistant/Security Manager; China Telecom - Tianyi Anti-Spam; China Broadcasting Network - China Broadcasting Network Business Hall), which is extremely user-friendly for iPhones that do not have built-in anti-spam services.

However, this official account-based blocking mode also has its own drawbacks: if there are any missed calls, users must enter the official account and mark abnormal calls through complex submenus. The spam recognition capabilities built into the mobile phone system are deeply integrated into the phone's call app, allowing users to easily mark relevant calls and share blocking lists in the cloud among different users.

Image source: Leitech

Based on data marking by a vast number of users, mobile phone brands can maintain their own blocking lists at a higher frequency. In response to situations where some companies "use employees' private numbers to make spam calls," they can also respond more quickly.

The logic of third-party apps is similar to that of built-in apps: Apps like Tencent Mobile Manager have a huge database of marked numbers and a recognition model for spam behavior based on years of user data. However, allowing third-party apps to access one's communication records may also pose certain information security risks.

Overall, operators provide a more fundamental, widely covered, and stable protective foundation, while mobile phone manufacturers and apps complement with "more accurate recognition and additional features." Therefore, from the user's perspective, the ideal approach is not to choose one or the other, but to "have them all": using operator services as the first line of defense against spam, combined with the blocking services of the mobile phone system, to ensure no calls are missed.

But then again, since relevant departments and operators are well aware of how annoying spam calls are, why not ban them from a legal perspective?

Why do spam calls and messages persist despite repeated prohibitions?

Despite the increasingly sophisticated anti-spam measures on the user side, telemarketing persists. Ultimately, this is tied to the "illegal cost" of telemarketing harassment.

Firstly, spam calls are often backed by mature industrial operation modes, and even some operators have their own "10,000-number" for promotional calls—10016. Moreover, as mentioned earlier, to avoid the risk of corporate real-name numbers being blocked, some companies will ask employees to use their personal mobile numbers or even utilize outsourced call services to make spam calls. This "guerrilla warfare" of "changing numbers after each call" significantly increases the difficulty of supervision.

Image source: Leitech

More importantly, there are still gray areas in the enforcement of relevant laws. Although regulations such as the Personal Information Protection Law and the Advertising Law have made clear provisions on the illegal collection and use of users' contact information and telemarketing without consent, due to the involvement of too many departments and the lengthy law enforcement process, telemarketing harassment has an extremely low illegal cost and is rarely dealt with severely.

Of course, we can also learn from overseas experiences: The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in the United States launched the "Do Not Call" list in 2004, prohibiting companies from making telemarketing calls to mobile numbers on the list, or they will face heavy fines. Countries like Australia have also followed suit with similar services; although Japan does not have a nationwide "Do Not Call" list, it also stipulates that "if users expressly refuse, companies must not continue to make calls."

In contrast, domestic governance of telemarketing calls still primarily focuses on technical means of "blocking," which can only ensure that users do not receive spam calls but cannot prevent related companies from making them.

Even if we "don't make calls," can we eliminate spam information?

But then again, the emergence of WeChat as a chat tool has already impacted traditional telephone and SMS services. With the popularity of services like WeChat Voice, which is similar to VOIP (domestic authorities have strict control over VOIP services), the influence of "phone calls" has begun to wane. On platforms like Weibo and Xiaohongshu, many young people express their "fear of making phone calls" and have a natural aversion to unknown incoming calls.

But this does not mean that telemarketing harassment will end as a result. The reason is simple: as long as there are users who will answer and can generate conversions, there will still be individuals willing to repeatedly make low-cost calls, even if the success rate is extremely low. Especially in industries with high customer unit prices, even if only one customer is acquired out of thousands of calls, it is sufficient to cover the costs. And for marketing teams utilizing outsourced dialing services, making a call has almost no marginal cost.

Image source: WeChat

In other words, we cannot reduce the hit rate of spam calls by "not making calls." It is even foreseeable that as the conversion rate of voice channels declines, former spam call harassment will inevitably evolve into new forms, such as forcing new customers to scan QR codes to follow official accounts or sending promotional private messages or false "recommendations" on social platforms.

To truly get rid of spam calls, we cannot rely solely on cold treatment. We must strengthen real-name management and clarify illegal boundaries. Simultaneously, the industry should also establish a public list system akin to the "Do Not Call" mechanism, evolving promotional harassment from "no pop-ups on mobile phones" to "merchants dare not harass."

It is hoped that in the future, we will usher in a truly clean communication environment. However, based on the current situation, there is still a long way to go from "do not disturb incoming calls" to "no disturbance from incoming calls."

Source: Leitech

Images in this article are from: 123RF Licensed Image Library. Source: Leitech