Takeout War 2025: Battle Reports May Deceive, But Battle Lines Do Not

![]() 07/18 2025

07/18 2025

![]() 607

607

This article is written based on public information and is intended for information exchange only and does not constitute any investment advice.

Starting last weekend, the instant retail "takeout war" suddenly escalated, with major platforms increasing subsidies to compete for market share. Order volume battle reports hit new highs, capturing significant attention.

Undoubtedly, this is a long-planned feast of capital and traffic. However, when we try to delve into the current state of this instant retail war, we will find that appearances greatly outweigh substance.

Looking back at the past two decades of Internet "subsidy wars," from group buying to ride-hailing to payments, a clear "iron law" emerges: The key to victory has never been the scale of subsidies alone, but the critical infrastructure capabilities hidden behind the competition.

History serves as a mirror. Whether it is Meituan's ground promotion army in the group buying war, Didi's ultimate transport capacity in the ride-hailing war, or the meticulous social and commercial scenarios in the payment war, the ultimate battlefield of each round of war has never been a subsidy show, but an ultimate test of infrastructure capabilities.

Order data is the battle report, and system capability is the battle line. Battle reports may deceive, but battle lines do not.

This war will be no exception.

As subsidies become increasingly homogenized, the true dividing line determining the final outcome of the war will shift from the "eyeball effect" to the game of fulfillment capabilities and local supply networks.

01

The Key to Victory: Fulfillment and Supply Capabilities Become the Strongest Lever

First, let's take a look at the latest battle reports of the takeout war:

1. JD.com's takeout service announced a breakthrough of 25 million orders last month, and has not released new order volume data as of press time this month.

2. After breaking through 80 million orders on July 5, the "rush day," Taobao Flash Sale + Ele.me platforms once again surpassed 80 million orders on July 12.

3. Meituan's peak order volume last year (the first autumn milk tea) was approximately 90 million. On July 5 this year, the order volume exceeded 120 million, and the peak on July 12 even surpassed 150 million.

Judging from the existing data, without significant subsidies withdrawing, the growth rates of the three platforms are gradually stratified: Although JD.com has not updated its order volume data in the past two weeks, the current overall scale has lagged behind the two major established players.

Taobao Flash Sale and Ele.me have strong industry accumulation and have achieved rapid growth in a short period of time through subsidies (from 30 million to 80 million). However, the momentum on the second week's rush day significantly weakened, and growth slowed down.

Although Meituan has the largest base, it currently has greater growth potential. In the first half of the year, Meituan's overall subsidy intensity was not as strong as that of Taobao Flash Sale and JD.com. After increasing subsidies in the past two weeks, its peak order volume jumped from 90 million to 150 million.

From the perspective of absolute growth, Meituan achieved the incremental levels of Taobao Flash Sale in three months (since its launch) and JD.com in half a year with less than one month of capital expenditure.

Without considering the differences in subsidy intensity (currently, the subsidy intensity of the three platforms is high), it is clear that, as we expected, Meituan has the highest ROI and the best effect in the subsidy war, followed by Taobao Flash Sale, and JD.com is currently slightly inferior.

Is it caused by differences on the demand side? Obviously not:

According to the latest report on instant retail industry traffic competition released by Questmobile, before the increase in subsidies, JD.com's "Instant Delivery" module had a monthly active user base of 165 million, with an increase in open frequency of over 51.1%, and a monthly active scale of about one-third that of Meituan. However, after increasing subsidies, its peak order volume accounted for less than 20%.

Taobao Flash Sale has a user base of about 457 million, approximately 90% of that of Meituan. After increasing subsidies, its peak order volume was only about half that of Meituan.

Simply put, they are all giants with users, but the difference lies in order volume.

The real difference between the three lies in the construction of fulfillment infrastructure capabilities:

JD.com is limited by its late entry disadvantage, and its basic supporting system requires long-term construction. Now it has extended its battle line into hotel and travel, raising questions about whether its capital volume is sufficient.

Taobao Flash Sale has integrated Ele.me's resources, giving it a significant advantage over JD.com. However, it is limited by its scale disadvantage over the past few years (Ele.me only has one-third the order volume of Meituan), and the growth space it can accommodate is relatively limited.

Meituan has the strongest fulfillment capability. Even at a peak of 150 million orders, its fulfillment network remains stable under short-term high-concurrency orders. Except for brief anomalies in the app due to peak traffic, there have been no order jams in merchant supply, rider fulfillment, consumer experience, and other aspects, unlike other competitors.

According to Meituan's battle report, 99% of orders were successfully delivered to consumers, with an average delivery time of 34 minutes last week. This is not only significantly better than its peers but also better than its own performance on July 5 the previous week.

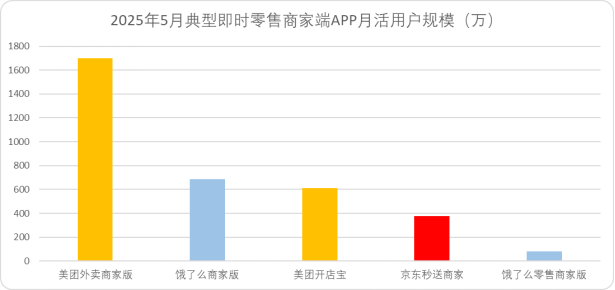

At the same time, Meituan has also accumulated sufficient advantages on the supply side. According to Questmobile's report on instant retail industry traffic competition, before the subsidy war began, Meituan's scale of monthly active users on the instant retail merchant-end app was much higher than that of its competitors, naturally enabling it to maintain a higher order volume growth scale and break through the ceiling.

Figure: Monthly active user scale of typical instant retail merchant-end apps, Source: Questmobile

The value of the moat of Meituan's local supply and fulfillment network built over the past decade is still deepening.

Against the backdrop of homogenized subsidies, this know-how can bring significant advantages, and the leverage driven by backend capabilities represented by fulfillment is increasing.

After all, every round of subsidy wars among Internet platforms is a capital carnage. What determines success or failure is often not the absolute value of capital scale, but the return on investment.

02

Misconception: Takeout Business Is Not About Traffic

Since the core reasons for restraining growth are fulfillment and supply capabilities, why are major platforms still continuously trying to increase capital investment and attempt to create order volume prosperity despite the unfavorable ROI?

Essentially, this is a manifestation of the failure of e-commerce platforms' accumulated know-how in the instant delivery market.

In the book "Influence" published in 2006, renowned psychologist Robert Cialdini elaborated on six principles that influence others' psychology. Applied to modern marketing behavior, the mainstream narrative of influence in the Internet era has gradually shifted from "authority" to "social identity," meaning that mass consumers are no longer easily swayed by professional media but are more willing to believe in result-oriented social consensus.

The most typical example is the teasing of Pop Mart: Before going public, investors evaluated Wang Ning, the founder of Pop Mart, as having average academic qualifications, no work experience, a calm expression, no charisma, and no elite team members. After going public, investors described Wang Ning as having a steady personality, not talking much, not showing his emotions, and possessing many excellent qualities of a consumer industry entrepreneur.

This seemingly "double-standard" evaluation system is a typical representative of the influence of social identity. Internet giants have firmly believed in this theory over the past few years: As long as the performance looks good, regardless of how bumpy the implementation process is, there will always be someone to justify it for them.

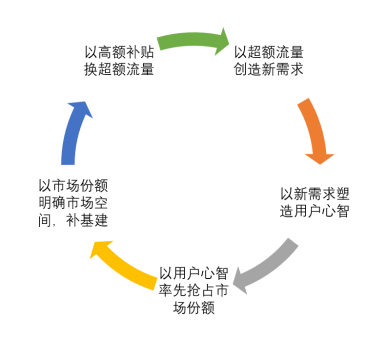

As a result, Internet giants have formed a seemingly reasonable methodology: Short-term reliance on subsidies to exchange for traffic, relying on traffic to drive awareness, relying on awareness to shape mindset, and finally converting user mindset into long-term market share before gradually making up for infrastructure deficiencies.

For example, if you remember, during the early shopping festivals, the fulfillment cycle for purchasing goods was often over a month. Essentially, platforms exchanged excess traffic for subsidies in a short period, and the supply side could not keep up.

However, retail businesses have a significant advantage: As long as demand is created, the supply side can make up for the gap through advance stockpiling and production line reuse. Therefore, Internet platforms have run through the business logic of exchanging subsidies for peak order volume, gaining social recognition through short-term order volume, slowly making up for shortcomings, and ultimately achieving conversion.

But in the takeout market, this logic actually does not work:

First, consumers' demand for material goods can be created out of thin air, but their demand for calories is constant. Even if social recognition is generated, it is ultimately difficult to convert into long-term market share.

Second, catering supply is different from retail and cannot achieve batch outbreaks within a certain period through advance stockpiling and production line reuse. If one insists on matching supply with peak order volume, regardless of whether the catering industry has this capacity, it will ultimately lead to invalid overflow of capacity under constant demand.

The essence of takeout is localized non-standard product transactions, and the key to its success lies in the dynamic balance between supply, fulfillment, and user demand. Pure price subsidies only stimulate demand. If supply is insufficient or fulfillment is unstable, the entire ecosystem will become unbalanced, ultimately damaging the instant delivery market itself.

Applying the logic of e-commerce subsidies to takeout and thinking in terms of traffic will inevitably lead to incompatibility.

If JD.com and Taobao pursuing peak order volume is due to the shackles of old e-commerce thinking, then why has Meituan, as the absolute leader in takeout, also chosen to increase subsidies to boost order volume?

We may find the answer in Wang Puchong's interview with LatePost: "Only the victor can say that fighting is meaningless. When a loser says so, it's just to save face. If we don't fight, they will consider us losers." Although Meituan knows that takeout is not a traffic business, they cannot ignore the influence logic of social identity.

The core logic is still to "show off muscle".

At the same time, Wang Puchong also said: "We didn't want to get involved, but we were passively dragged in. Now that we're in it, we have to tell the industry the truth about rushing orders - you want to do as many orders as you want, I'll tell you we can do it, and do it at a lower cost. We're not trying to achieve a certain number of orders; we want to show the industry that doing orders is easy."

In the future, we may soon see even more astronomical peak order data, but is such a comparison meaningful? For e-commerce players to truly make breakthroughs in takeout, they must abandon path dependence and return to enhancing fulfillment capabilities and user experience.

03

The Sooner You Realize Your Mistake and Return, the Better. The Strong Subsidy Vicious Circle Must Be Avoided

Of course, regardless of differences in perception of peak order volume or the takeout business, the urgent problem that needs to be addressed now is that subsidy wars should not continue indefinitely.

Returning to the takeout war itself, the core motivations for e-commerce players entering the takeout market are twofold:

The first is to hope that high-frequency catering demand will drive low-frequency retail demand, pursuing entrance traffic.

The second is to truly recognize the huge potential of the instant delivery market and hope to build a comprehensive instant delivery system through takeout.

Neither of these demands can be achieved through "strong subsidies".

The paradox of subsidies for the first demand lies in the fact that the final outcomes of subsidy wars in the past, such as those between Uber and Lyft, OFO and Mobike, and community group buying, all show a clear pattern: The conversion rate and LTV (lifetime value) of users acquired through subsidies are extremely low.

Historical experience tells us that subsidies attract "price hunters" rather than users with genuine demand. The entrance traffic brought by these users cannot be converted into high-value e-commerce retail traffic.

Wang Puchong said bluntly: "The total market volume of instant retail has doubled from 100 million orders at the beginning of the year to 250 million orders, most of which are bubbles. In Suqian, where the takeout war is most intense, the order volume has quadrupled, but there are very few new users in the actual takeout business."

Meituan, which has experienced multiple rounds of fierce competition in the offline service market, clearly understands this principle:

Since June this year, Meituan's instant retail orders have consistently remained above 90 million, with the market share of food orders consistently maintaining around 70%. This means that compared to the non-rigid demand growth of "milk and coffee," Meituan's growth is more in line with natural growth laws, and its user value is higher.

The paradox of subsidies for the second demand lies in the fact that if one wants to build a comprehensive instant delivery system, the focus of capital should be on pursuing broader supply and a more complete user experience. Excessive pursuit of demand generated by subsidies and neglect of fulfillment and user experience will only undermine the healthy development of the instant delivery market.

Therefore, when the number game of "subsidy battle reports" becomes rampant, we should look beyond appearances and Insight the essence. The vitality of takeout and even the entire instant retail sector is rooted in its unique attributes of localization, non-standardization, and high timeliness.

Endless "strong subsidy" competitions are not only a tremendous waste of capital efficiency but may also distort market signals, overdraw industry health, and ultimately lead to supply imbalance and experience collapse.

The endpoint of competition should not be data comparison but the healthy development of the entire instant retail ecosystem.