Jingdong Launches Independent Food Delivery App, Disproving 'Food Delivery as a Traffic Driver for E-commerce'

![]() 11/21 2025

11/21 2025

![]() 555

555

This article is written based on publicly available information and is intended solely for informational exchange, not as any form of investment advice.

On the evening of November 13, JD.com released its third-quarter financial report, showing revenue of RMB 299.1 billion, up 14.9% year-on-year; however, net profit was only RMB 5.3 billion, down 54.7% year-on-year. The key reason for the sharp profit decline lies in the food delivery business: data shows that the overall profit margin of JD's retail and logistics businesses improved by 60 basis points in the first three quarters, indirectly confirming that the key drag on profitability was the food delivery segment within the new business sector.

Although the market had anticipated JD's 'revenue growth without profit increase'—after all, the third quarter marked the peak of this year's food delivery subsidy war—the nearly 50% profit decline still fell significantly below market consensus expectations.

From a short-term investment perspective, JD's foray into food delivery has been far from successful. However, Liu Qiangdong previously articulated his business logic in an interview: 'I can forever forgo profits from selling meals on the front end as long as I make money through the supply chain.' Clearly, he once viewed food delivery as a traffic driver for e-commerce transactions.

With this goal in mind, JD Food Delivery was integrated into the main JD app from its first day of operation, with a dedicated entrance on the homepage. Inspired by JD, Alibaba launched Taobao Flash Sales, and shortly thereafter, Ele.me officially rebranded and fully integrated into Taobao.

However, soon after releasing the third-quarter financial report, JD announced the launch of an independent food delivery app. This move seems to declare the failure of the 'food delivery as a traffic driver for e-commerce' strategy.

What issues warrant consideration in JD's sudden strategic shift in food delivery?

01 Conclusion: Food delivery as a traffic driver is neither cost-effective nor effective

To understand why JD launched an independent food delivery app and abandoned its main-site traffic strategy, we need to examine two key calculations:

First calculation: Is food delivery cost-effective as a traffic driver?

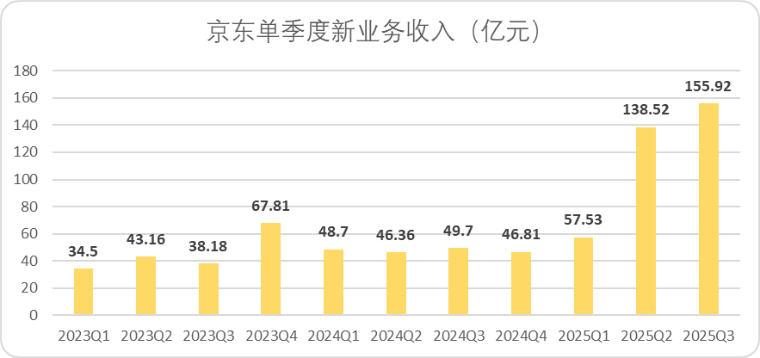

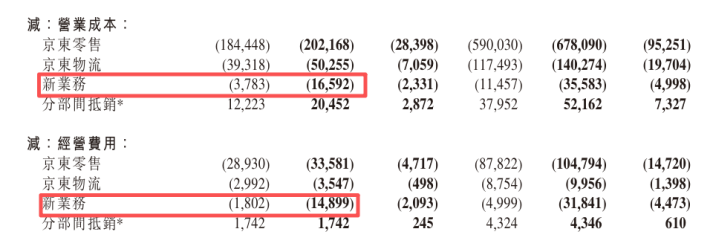

JD's new business segment includes food delivery, JD Property, JX (Jingxi), and overseas operations. Excluding Dada (with minimal revenue impact) briefly included from the second half of last year to the first quarter of this year, the revenue structure of this segment has remained relatively stable.

This year, JD has made frequent moves in overseas operations, acquiring European e-commerce platforms MediaMarkt and Saturn, as well as Hong Kong's Jia Bao Supermarket. Assuming these acquisitions are not consolidated (as clarity is lacking), we can tentatively attribute the entire revenue increase in new businesses during the second and third quarters of this year to food delivery—totaling approximately RMB 19.8 billion.

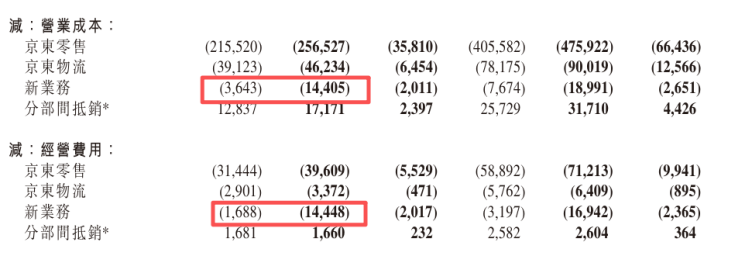

In terms of costs, the new business segment saw a net increase of RMB 25.9 billion in operating costs during the same period, along with a RMB 23.6 billion increase in operating expenses. This means that while generating RMB 19.8 billion in additional revenue, approximately RMB 49.4 billion in new costs were incurred. If food delivery serves merely as a traffic driver, such costs are excessively high. This explains why the financial report emphasized 'narrowing investments in new businesses.'

Figure: JD's Q2 new business operating costs and expenses. Source: Corporate financial report

Figure: JD's Q3 new business operating costs and expenses. Source: Corporate financial report

Food delivery itself is a low-margin, long-chain, high-fulfillment-cost business with extremely low leverage efficiency.

Among all platform-based business models, food delivery represents a typical 'five-dimensional commercial model.' Ride-hailing operates in three dimensions (passengers, drivers, platform), while e-commerce operates in four (adding 'products'). Food delivery, however, must coordinate five key elements: platform, merchants, customers, products, and delivery riders. Each element requires subsidies and operations, leading to high costs and thin margins.

The outside world often assumes food delivery platforms 'profit from three sides,' but in reality, they 'subsidize three sides'—users, merchants, and riders. Each side requires subsidies, and the entire industry relies on platform subsidies to sustain itself. Both past JD and current Taobao Flash Sales repeatedly validate a fact: once subsidies stop, engagement vanishes.

Second calculation: Has food delivery driven e-commerce revenue on the main platform?

Given the substantial investments, has food delivery, as envisioned by Liu Qiangdong, effectively driven retail growth on the main platform despite its own lack of profitability?

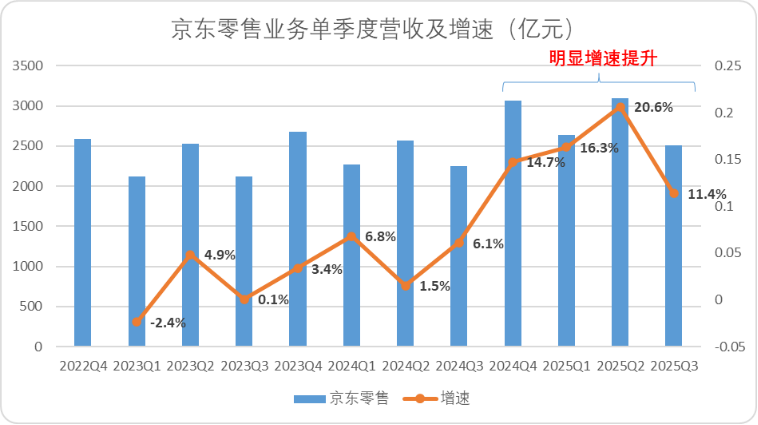

On the surface, JD's retail business has shown impressive growth this year: revenue growth rates for the first three quarters were 16.3%, 20.6%, and 11.4%, respectively, jumping from single-digit to double-digit percentages compared to the past.

However, a closer timeline reveals that JD's food delivery business only began rolling out in late March and early April of this year, while the retail growth acceleration started in late Q4 of last year.

The true driver of JD's retail surge was the 'national subsidy' policy implemented late last year. CITIC Securities research shows that during the Double 11 period, JD captured 50.1% of the home appliance category and 54.1% of the 3C digital category, showcasing significant advantages in electronics. This explains why retail growth slowed markedly in Q3—primarily due to the phasing out of national subsidies.

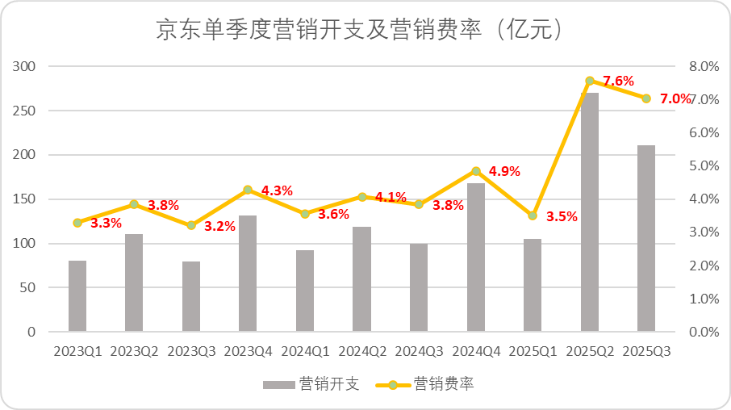

Moreover, cost structure analysis reveals another clue: marketing expenditures related to food delivery only surged in Q2 and Q3 of this year, while retail revenue began rising late last year and peaked in Q2 of this year. It is difficult to attribute retail growth to food delivery traffic.

CEIC Data also shows that since 2021, the online penetration rate for e-commerce has largely plateaued, with the proportion of online retail sales of physical goods to total retail sales of consumer goods stabilizing between 24%-27% over the long term. Future scenarios where traffic drives expansion of online physical retail supply are unlikely.

Figure: Proportion of online retail sales of physical goods to total retail sales of consumer goods. Source: CEIC Data

More direct evidence comes from CITIC Securities' analysis of this year's e-commerce promotions: instant retail scale remains far lower than traditional e-commerce, accounting for only about 1% of total e-commerce GMV, with cross-selling ratios to traditional e-commerce still low.

In summary, food delivery as a traffic driver is neither cost-effective nor effective in driving e-commerce growth. Its underlying logic of driving e-commerce through food delivery traffic may have been flawed from the outset.

02 Core Issue: The 'Mental Accounting' Paradox in Behavioral Economics

Nobel laureate in economics and University of Chicago professor Richard Thaler proposed the 'mental accounting' theory. In his 1985 paper 'Mental Accounting and Consumer Choice,' he recounted an experience:

Once, while lecturing in Switzerland, he earned a substantial fee and decided to travel locally, having a fantastic time—despite Switzerland being one of the most expensive countries globally. Later, while lecturing in the UK with similarly generous compensation, he traveled to Switzerland again but found everything prohibitively expensive and the experience unpleasant.

Why did the same consumption in Switzerland, with comparable income, yield such different perceptions? Thaler argued that behavioral balance is only achieved when income and expenses belong to the same 'mental account.'

This theory reveals a fundamental business truth: not all high-frequency consumption can effectively drive low-frequency consumption.

Take Meituan as an example: by using 'dining' and food delivery as traffic entry points, it leverages high-frequency engagement to drive low-frequency services, gradually penetrating offline services, travel, and other scenarios. This path follows a clear linear logic: the 'dining' aspect of food delivery aligns in essence with on-site dining, making business promotion cohesive. 'Eating, drinking, and entertainment' naturally extend to services like transportation and phone charging, then further to travel and cultural tourism in different locations.

However, transitioning from 'dining' to 'shopping'—especially high-value, low-frequency categories like home appliances and 3C products—yields uncertain conversion rates. Significant differences in average order value, target demographics, and purchase frequency make it difficult to share the same 'mental account.'

Figure: Mental accounting illustration. Source: Baidu Baike × Hunzhi · Comic Knowledge

History offers numerous examples of high-frequency driving low-frequency strategies failing due to mismatched mental accounting.

For instance, despite Tencent's massive social traffic, it failed to capture market share from Taobao through Paipai. Similarly, DoorDash's rise to surpass Uber Eats underscores that not all high-frequency scenarios naturally extend to low-frequency consumption; success depends on whether positioning and pricing attributes make consumers feel the expenses come from 'the same wallet.'

While some synergy exists between food delivery and e-commerce, it should be viewed as a passive convergence of business networks driven by market forces—a natural outcome rather than a strategic goal. The core hub connecting these networks—the efficient 'converter'—remains elusive even after over a decade of exploration by Meituan and Ele.me.

From a business logic perspective, treating food delivery as a tool rather than a core business reverses priorities. Meituan succeeded in food delivery first, then expanded organically into flash sales, travel, and transportation, with food delivery traffic flowing naturally along this path. JD, however, started with food delivery for its traffic, aiming ultimately to drive e-commerce.

E-commerce is the goal; food delivery is the means. When misaligned, this becomes 'mistaking the means for the goal.' Similar failed models abound in internet competition history.

Since food delivery serves merely as a traffic driver, platforms lack genuine incentive to invest fully. This intent gradually becomes apparent to users and riders, affecting user acquisition and retention in food delivery, thereby hindering conversion to e-commerce.

A hidden risk lies in the excessive cost of this tool: the food delivery business model is poor, and both JD and Alibaba may have underestimated the capital and complexity required for food delivery investments.

Recently, Liu Qiangdong remarked, 'Many users struggle to find the JD Food Delivery entrance, and even with the Miaosong channel in the main JD app, some users experience poor service and traffic loss.'

These candid remarks indirectly reveal the difficulty of achieving mutual conversion between food delivery and e-commerce.

In contrast, Jiang Fan remains committed to the 'super consumption platform' strategy, transforming Taobao into a mega consumption portal. Even Ele.me, independent for over a decade, has adopted an orange brand identity and fallen under the 'Flash Sales' umbrella.

E-commerce platforms' approaches to food delivery have diverged: Taobao persists with a 'unified' strategy, repeatedly validating food delivery's synergy with e-commerce, while JD has pivoted sharply with an independent app.

In this context, it is hard to declare 'experience triumphs over youth'; rather, the market is returning to fundamentals: at this stage, food delivery is not a rational traffic driver for e-commerce platforms.

03 Strategic Shift: What Does the Independent Food Delivery App Signify?

JD's launch of an independent food delivery app marks a clear strategic pivot, indicating a critical reassessment of its food delivery business. The company now recognizes that treating food delivery as a mere e-commerce traffic driver is neither cost-effective nor sustainable. The business must transition away from subsidy dependence toward independent accounting and self-sufficiency. This shift reflects a correction and reconstruction of its original business logic.

Separating food delivery from e-commerce represents a more rational choice.

However, as previously discussed, the food delivery business involves complex chains and numerous links. Without full commitment, early capital investments risk becoming sunk costs. The business requires coordination across delivery, operations, merchants, and users; failure in any link threatens the foundation—a reason why platforms like Douyin and Baidu swiftly exited the sector.

Guosen Securities' latest research estimates that even considering cross-selling effects among food delivery, instant retail, and traditional e-commerce, JD may still face profitability gaps by 2030 under conservative assumptions.

Why, then, does JD persist with food delivery and even develop an independent app?

Financial report details suggest another strategic intent: capturing merchant mindshare and reshaping valuation logic.

Before venturing into food delivery, JD was perceived in capital markets as a 'capital-intensive, low-margin' business, with its valuation under persistent pressure.

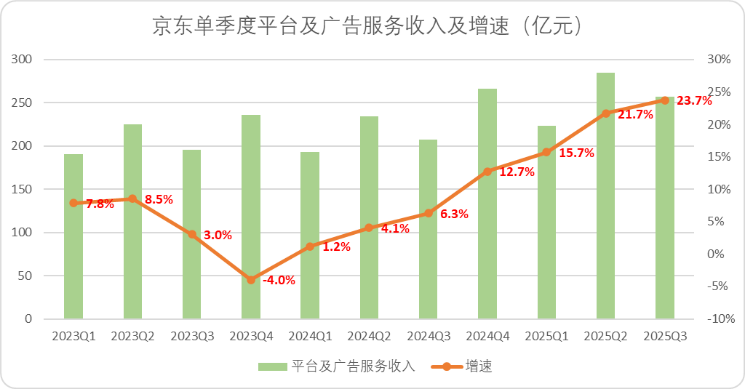

Since entering food delivery, however, among JD's various revenue streams, only platform and advertising services income—which synchronously grew with the food delivery business—remained unaffected by the phasing out of national subsidies.

Further examination of JD's retail profit margins reveals a notable Q3 improvement, primarily driven by advertising revenue boosting the monetization rate and helping JD shed its 'tough business' label—a long-term goal.

How did JD achieve this? Clues lie in financial reports and earnings call statements: JD repeatedly emphasizes surpassing 700 million users, but its target audience may not be ordinary consumers but the vast supplier base previously concentrated on Taobao.

JD likely understands that food delivery's actual conversion rate is unstable. However, when advertisers observe surging platform traffic, they become more inclined to open stores on JD. As third-party (3P) merchants increase, advertising revenue naturally rises.

This is also evidenced by the revenue structure: In the third quarter, the year-on-year revenue growth rate of JD.com's clothing, footwear, and headwear category reached approximately eight times the industry average. It can be said that while JD.com was fiercely competing with Meituan in the food delivery battlefield, it ultimately 'stole Taobao and Tmall's home'.

JD.com naturally understands that relying on new businesses like food delivery for 'brand promotion' is difficult to sustain. Although food delivery is hard to directly convert into e-commerce orders, it is enough to change the perception of JD.com among e-commerce merchants who urgently need new traffic. Once the perception transformation and settle in (which means 'settling in' or 'joining') of merchants are completed, there is no need to continue investing more resources in the 'bottomless pit' of food delivery.

Therefore, launching an independent App, scaling back investments, and proposing that 'the food delivery business should survive independently' are actually rational adjustments by JD.com after achieving its phased objectives (which means 'phased goals'). This marks the transition of the food delivery business from the 'strategic trial and error' phase to the 'tactical cleanup' phase.

However, it must be pointed out that JD.com still faces a series of fundamental issues: After breaking away from the storyline of e-commerce traffic diversion, what exactly will enable food delivery to survive independently? Is it higher delivery efficiency? Lower customer acquisition costs? Or a stronger merchant ecosystem?

After all, an independent App is merely a financial and organizational separation and does not automatically lead to healthy business operations. If JD.com fails to establish true operational efficiency, scenario barriers, or differentiated value in the food delivery sector, then today's 'independence' is merely another capital narrative that packages 'strategic trial and error' as 'strategic transformation'.