"Japanese Chip Tragedy"

![]() 09/24 2024

09/24 2024

![]() 479

479

"The world is watching us."

In the 1970s, Japan's rapidly developing semiconductor industry after World War II encountered the "black ship's attack" from the United States. While wielding the big stick of trade sanctions, the US vigorously pushed giants like IBM to enter the "Edo Bay" with high-tech advancements.

Forced to open its markets, Japan's semiconductor industry faced a daunting situation. In response, Japan secretly launched a counterattack—

Led by the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) and with the collaboration of five major Japanese companies, a "Semiconductor Joint Fleet" was formed to tackle the "choking" problem of core technologies through a national approach, catching up with and surpassing US semiconductor technology.

[Japan's "National System"]

One day in early 1976, the Kioicho area of Tokyo's Chiyoda ward was bustling with people.

This was a Japanese restaurant founded in 1939, renowned for its cuisine and interior design, with a Michelin two-star rating and a popular choice for banquets among Japan's political and business elites.

The hosts of this banquet were MITI (now the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry) retiree Masato Negishi and Takao Tarui, who worked at the Electrotechnical Laboratory of MITI. The presidents of Japan's five largest computer companies at the time—Hitachi, Fujitsu, Toshiba, NEC, and Mitsubishi Electric—were all in attendance. Before the banquet began, Negishi told Tarui:

"Your task today is to drink with the presidents and make sure they're well taken care of."

Tarui, with a background in technology development, was neither a heavy drinker nor adept at socializing, earning him a scolding from Negishi. "Brother, you're too stiff. It'll be hard for you to work effectively in the future!" Tarui later realized that Negishi meant for him to bond with the presidents, ideally to the point of brotherhood, to lay a foundation of trust for future project cooperation.

This project was vital to Japan's national interests—it was later recorded in history as the "Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI) Technology Research and Development Project" ( exceed LSI Technical Research Group , LSI: Large Scale Integration, hereafter referred to as "VLSI").

Its core operation and purpose were for MITI to lead and collaborate with five major companies to form a joint research institute for technological development, catching up with and surpassing the semiconductor technology of giants like IBM in the US, reversing Japan's passive position in the semiconductor industry.

In familiar terms, it was about concentrating efforts to accomplish great things through a "national system."

It is common for major powers to use a "national system" to "concentrate efforts to accomplish great things" in industry and technology.

For example, the Oscar-winning film "Oppenheimer" tells the story of the US concentrating efforts to develop the atomic bomb during World War II. Similarly, the former Soviet Union adopted a "mobilization" model, spanning politics, military, industry, science, and education, to achieve groundbreaking results like successfully launching the world's first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, in 1957, beating the US.

Japan has refined this approach and developed a mature operational system. At its core is the grand cooperation between industry, academia, and government, officially known as the "Organic Development System" and "Integrated Promotion System," where:

The "Organic Development System" focuses on bridging the technology gap with advanced countries by providing state funding for national research institutions, industry, and academia to collaborate on tackling critical and urgent large-scale industrial technologies essential to the national economy, especially those with long research and development cycles, high investments, and technologies that private enterprises cannot handle independently due to their complexity.

The "Integrated Promotion System" aims to reform the science and technology system. When Japan perceived a lack of creativity in the science and technology sector and administrative and research institutions becoming complacent, the state took the lead in clarifying responsibilities, promoting institutional reforms, and enhancing R&D vitality through the aforementioned industry-academia-government collaboration model to initiate and advance large-scale R&D projects.

After World War II, Japan rapidly developed its electronics industry by importing and innovating upon US technology, imposing tariff barriers, supporting government procurement, and enacting laws like the "Temporary Measures for the Revitalization of the Electronics Industry." This self-strengthening of the computer industry reduced its import dependence from 69% in the early 1960s to just 21% by the early 1970s, with domestically produced models even outselling foreign ones in the market.

However, this soon alerted the US. Subsequently, the US, which had previously supported Japan, changed its stance, leading to frequent trade frictions. While pressuring Japan to open its integrated circuit market at the government level, the US continued to make breakthroughs at the corporate level, surpassing Japan's semiconductor industry with advanced technology.

In 1970, IBM introduced the 370 series of computers based on large-scale integration circuits, outperforming Japanese counterparts in both technology and performance, severely impacting Japan's computer industry.

To catch up with the US, Japan invested 57 billion yen to fund a consortium of companies. However, just as they were catching up, IBM dropped another bombshell, further widening the gap.

In 1975, as Japan was just starting to produce computers with 1K DRAM memory chips, IBM announced the development of its fourth-generation Future System computers based on 1M DRAM VLSI chips.

Akira Tanaka, the driving force behind the VLSI project and head of the Japan Electronics and Information Technology Industries Association, later recalled, "Without the national project, we had no way to master this technology."

Moreover, after the semiconductor market opened up, Japan's consumer electronics industry faced a crisis of being eroded by the US.

At this critical juncture, Japan once again activated its "national system," forming a "Semiconductor Joint Fleet" to attack across the Pacific, leading to the banquet arranged by Negishi and Tarui to bond with the presidents.

[Semiconductor "Joint Fleet"]

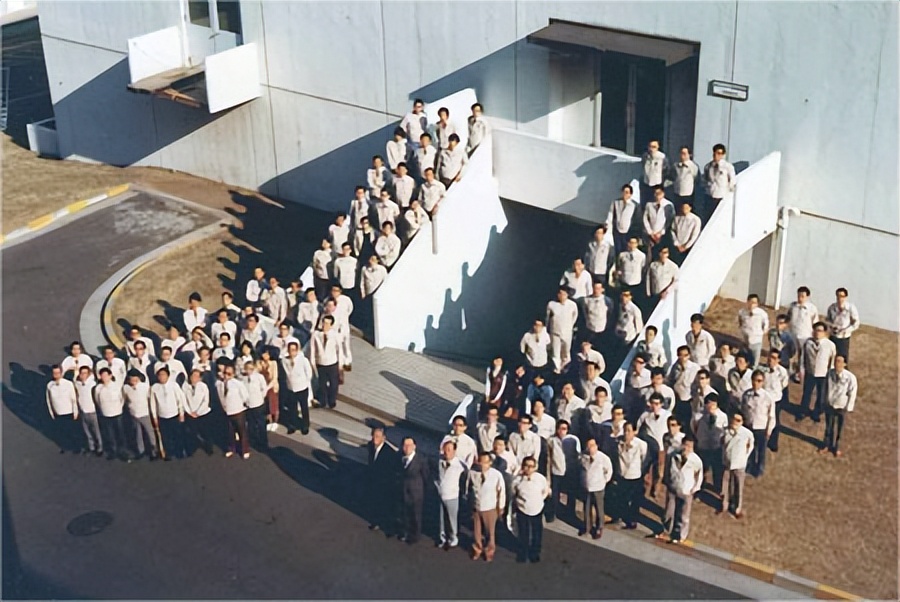

At the heart of the VLSI project's "Joint Fleet" was a "Joint Research Institute" comprising 20 technical experts each from Hitachi, Fujitsu, Toshiba, NEC, and Mitsubishi Electric, totaling 100 members.

The "Fleet Admiral" was appointed by MITI and was responsible for administration. This role fell to the retired Negishi, an industrial veteran with extensive experience in national-level project management. Tarui, a graduate of Waseda University's First Institute of Science and Engineering with a specialization in electrical engineering, was in charge of technical coordination. Having applied for a transistor-related patent in 1958, he was one of Japan's earliest experts involved in semiconductor development.

On the day the VLSI project commenced, all technical personnel gathered in front of the Joint Research Institute located within NEC's Central Research Laboratory for a group photo to commemorate the occasion. As engineers from Japan's top companies realized they were now part of the "national team," they were filled with emotion. Some later recalled feeling as if,

"The world was watching us."

▲ Group photo of key VLSI project members

To complete the VLSI project, balancing the interests of all parties and maintaining the enthusiasm of researchers was crucial beyond technical breakthroughs. The two project leaders achieved near-perfect synergy.

A scholar who interviewed Negishi once commented, "Negishi and Tarui have vastly different personalities, characters, and abilities. One is a seasoned administrative official skilled in socializing, while the other is a typical engineering expert, meticulous and dedicated to technology. For the VLSI project, they complemented each other perfectly."

The VLSI project focused on "microfabrication device development" and "silicon wafers." Within the five companies, research emphasis was placed on the practical development of 64K and 256K DRAM. Under these directions, the key challenge lay in microelectronic processing technology to significantly increase chip integration.

In March 1976, the VLSI project was divided into three teams to tackle the "choking" issues in VLSI, computers, and information systems. The specific division of labor was: Tarui's Joint Research Institute was responsible for basic and generic technology research; the Computer Comprehensive Research Institute established jointly by Hitachi, Mitsubishi, and Fujitsu, and the NEC-Toshiba Information Systems Research Institute focused on practical technology development.

Under Tarui's leadership, the Joint Research Institute had six research laboratories. The first three focused on microelectronic processing technology, the fourth on crystallization technology (led by the Electronics and Communications Research Institute), the fifth on process technology (led by Mitsubishi), and the sixth on testing, evaluation, and product technology (led by NEC).

During this process, disputes arose regarding the heads of the research laboratories.

There was no disagreement over the leaders of the last three laboratories, but the first three caused much contention. Microelectronic processing technology being a crucial foundational technology for semiconductors, all five companies vied for these positions to gain a stronger foothold in the core technology. Hitachi, Fujitsu, and Toshiba even "threatened" to withdraw from the joint research if they didn't get their way.

Behind this was the fact that the five companies had varying levels of R&D progress in microfabrication and were competitors in the same industry. Therefore, companies leading in this field worried about losing their technological advantages after joint research, while those lagging behind saw this as a golden opportunity they couldn't miss.

Ultimately, Negishi and Tarui resolved the crisis by allowing the leading companies to take the initiative. Hitachi, Fujitsu, and Toshiba each appointed a representative to lead the first three research laboratories.

Regular communication was crucial for a multi-pronged project.

To facilitate this, every one to two weeks, Tarui organized presentations by researchers from each laboratory to share progress. To further promote communication, collaboration, and transparency, he even arranged for the laboratories to be separated but deliberately left without doors.

Beyond human and intellectual resources and technological sharing, the R&D investment for the VLSI project was shared between the government and enterprises. Over the project's four-year duration, a total of 73.7 billion yen was invested, with 29.1 billion yen subsidized by the government and the remaining amount covered by the five companies.

There was a significant incident that highlighted the challenges of this collaboration: The five companies had initially hoped the government would increase funding to 150 billion yen to cover the entire R&D process and follow-up plans. However, after the government rejected this request, the companies became indifferent to the research institute, affecting morale, especially among the 100 engineers at the Joint Research Institute, some of whom lamented,

"We've been abandoned by our companies."

At a crucial moment, Tarui, who resonated more with the technical staff, turned the tide by appealing to patriotism:

"We work and live together every day. What are we striving for? Our competitors are not each other but IBM, the world's number one. So, let's stop guarding against and isolating each other. In the end, we're all in this together."

Inspired by Tarui, engineers from different companies once again united, abandoning their corporate identities and embracing their responsibilities and missions as part of the national team, marching towards their ultimate goal together.",["["Driving Alongside IBM"]

Another challenge for the VLSI project was conducting research secretly to avoid US obstruction and counterattacks.

There were indeed some heart-stopping moments during the process.

At one point, a Japanese newspaper published an article about the second research laboratory's achievements in variable matrix beams. Highly attentive to Japan's movements, Americans noticed this article and suspected that Japan had launched a national-level project in the semiconductor industry. These suspicions even escalated in the US.

This scared Tarui.

After much deliberation, he decided to take the initiative by disclosing information but not the truth.

Tarui suggested to Negishi that they publish a paper at the IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) in the US, introducing the VLSI project without revealing its core content, focusing only on basic research to dispel American suspicions.

Negishi then consulted with the five companies.

They unanimously agreed: "It's best not to mention even basic research or the Joint Research Institute."

In December 1977, at the Sheraton Washington Hotel in the US, Tarui appeared at the IEDM alone and delivered a keynote speech titled "LSI and VLSI Research in Japan."

Given the special context, over 600 people packed Tarui's presentation, with participants standing in the corridors unable to fit inside. Under the gaze of American peers, Tarui appeared well-prepared but delivered mostly a compilation of past research, concluding nervously and seriously stating:

"We will share more research results and explore the future of microelectronics together with the US."

However, the US remained vigilant.

Immediately after the conference, an American friend of Tarui who worked at Bell Labs approached him, probing:

"I heard your government subsidizes businesses, which is illegal in the US where the government and businesses compete. Do you know why there are 25 times more lawyers in the US than in Japan? Competition shapes society."

After the project's success, Tarui wrote in his memoir: "Upon later confirmation, I was accompanied by CIA agents everywhere I went in the US. It seemed the US government was waiting for me to slip up."

This was a common tactic of the US. Decades later, similar tactics were employed in Pierre Sahouani's "The American Trap" and the Meng Wanzhou incident involving Huawei.

Fortunately for Tarui, he returned safely to Japan. By taking the initiative, he successfully diverted American attention, allowing the project to avoid direct confrontation.

Gaining time and space, the Japanese concentrated their efforts on R&D, achieving continuous breakthroughs.

Key technologies like three types of electron beam lithography equipment, high-resolution masks and inspection equipment, silicon wafer oxygen and carbon content analysis, large-diameter single-crystal silicon growth technology, and CAD design technology were successively developed. With these technologies, logic and memory component manufacturing technologies emerged, enabling Japan to develop 256K DRAM a year ahead of the US, becoming a leader in this crucial field.

Under the sharing mechanism for the foundational research results of the VLSI project, the five participating companies also achieved leapfrog development in semiconductor technology, mastering the core technologies for the next generation of computers and breaking the US technological siege.

Armed with these advancements, Japanese companies launched a counteroffensive in the semiconductor industry, rapidly catching up and rewriting the balance of power with the US.

By 1986, Japan's global semiconductor market share had risen from 26% to 45%, while the US share fell from 61% to 43%. That year, six of the world's top ten chip manufacturers were Japanese companies.

NEC, Toshiba, and Hitachi ranked top three.

Unfortunately, Japan's technological breakthroughs ultimately failed to escape the competition and constraints of national strength.

Japan's semiconductor breakthrough, akin to a "Pearl Harbor" surprise attack, quickly woke up the United States. If technology couldn't win, legislation would be used. If legislation still couldn't win, other methods would be employed.

In 1984, the United States introduced the Semiconductor Chip Protection Act, explicitly proposing greater government support for the chip industry. In 1987, the Antitrust Act was amended to clarify that the US government could legally subsidize enterprises. Then, following Japan's example, the US government joined forces with 14 companies to establish the Semiconductor Manufacturing Technology Consortium (SEMATECH), focusing on chip manufacturing processes and equipment to technically counter Japan's advanced technology.

While strengthening itself, the United States also wielded the so-called legal weapon. Under Section 301 of its Trade Act, the Semiconductor Industry Association filed a lawsuit against Japan, forcing Japan to sign the Japan-US Semiconductor Agreement in 1986. The Agreement explicitly required increasing the share of US semiconductor products in the Japanese market to 20%.

Yasuo Tarui, who once led Japan's successful counterattack, was deeply disappointed and angered by this Agreement, describing it as:

"An unequal agreement that will go down in history."

▲ Negotiation scene of the Japan-US Semiconductor Agreement

While directly confronting Japan, the United States continued to eradicate Japan's semiconductor industry by supporting countries like South Korea. By the mid-1990s, Japan's semiconductor industry had completely fallen into decline and has yet to recover.

Looking back years later, Yasuo Tarui is still bitter about losing a good opportunity at the time, but his lesson is thought-provoking:

"Being number one in the world is not always a good thing. Japan struggled to reach the top spot, only to become a target and never recover after being suppressed by the United States.""It is noteworthy that after experiencing the "Lost Decade," Japan, with its economic growth recovering and stock market records being broken in recent years, has once again launched a charge at semiconductors."They were unwilling to accept defeat. When the Japan-US Semiconductor Agreement was signed, current Minister of Economy, Trade, and Industry, Shuntaro Fujimura, was a young official in the Ministry of International Trade and Industry."Last month, attending the groundbreaking ceremony of TSMC's Kumamoto factory, Fujimura told reporters:"I still vividly remember how the United States frantically weakened Japan's semiconductor industry competitiveness back then.""In August 2022, eight major Japanese companies established the semiconductor manufacturing company Rapidus, with the goal of mass-producing 2-nanometer process semiconductors by 2027. In September 2023, the groundbreaking ceremony for Rapidus' first factory in Hokkaido was held."For Japan, which can currently only produce 40-nanometer process semiconductors, the difficulty of achieving 2-nanometer production is magnitudes greater than that of the "Super LSI" project. Several obstacles need to be overcome, including: factories capable of manufacturing cutting-edge products; thousands of skilled technicians; the latest generation of extreme ultraviolet lithography machines; competing for customers against Samsung and TSMC; and an investment of 5 trillion yen."To this end, Rapidus is "uniting" all available forces, even turning former "enemies" like IBM into partners for collaborative research and development. Chunyi Koike, the 72-year-old president of Rapidus, who worked in chip manufacturing at Hitachi and Western Digital, recalls Japan in the 1980s and 1990s as:"We thought we could handle everything ourselves.""Currently, the Japanese government has pledged to subsidize Rapidus' 2-nanometer plan with $2 billion. If Rapidus wants more government funding, it must produce market-ready products. As the new captain of Japan's national semiconductor team, Chunyi Koike can only think about how to win:"Others may need three months to accomplish something, but we will finish it in one month. Because this is Japan's last chance.""[References]

[1] "Memories and Future Steps of the Super LSI Joint Research Institute" by Yasuo Tarui

[2] "Does Japan Have a 'National System' in Science and Technology? Insights from Semiconductor Technology Development" by Huimin Li, Rongping Mu, and Yue Hao

[3] "Chip Story: Understanding the Semiconductor Industry" by Zhifeng Xie and Daming Chen, published by Shanghai Scientific and Technical Publishers

——END——