From DeepSeek Panic to Cowork Panic

![]() 02/09 2026

02/09 2026

![]() 392

392

Cowork Panic May Be More Lasting Than DeepSeek Panic

By Shuhang, February 9, 2026

In February, global software stocks experienced a familiar sell-off.

On February 4, Thomson Reuters saw its largest single-day drop of 15.8%, LegalZoom plummeted nearly 20%, RELX fell 14%, FactSet dropped 10.5%, while Salesforce and Workday also experienced significant declines. The S&P 500 Software & Services Index fell nearly 13% over five consecutive trading days, down 26% from its October peak. Some traders referred to this as the "SaaSpocalypse"—the end of SaaS.

The trigger was Anthropic's launch of Claude Cowork on January 13, a general-purpose AI agent that extends the main capabilities of the interaction-unfriendly Claude Code to non-technical users, enabling them to read, edit, and create files on their computers. On January 30, Anthropic introduced 11 open-source plugins for Cowork, covering verticals such as legal, finance, sales, and marketing.

A super-simple conclusion emerged: If Claude Cowork users can achieve results comparable to ultra-expensive enterprise software using natural language commands, then the expertise and vertical experience accumulated by software giants based on the SaaS business model might be rendered obsolete.

Why does this feel familiar? Because a year earlier, the market panic triggered by DeepSeek followed a nearly identical pattern—both products were released over a week before being fully recognized by the capital markets, causing overnight panic.

On January 20, 2025, DeepSeek released its reasoning model R1, claiming a training cost of just $5.6 million while matching or surpassing OpenAI's o1 model in multiple benchmarks. A week later, on January 27, NVIDIA's stock plummeted 17%, wiping out nearly $589 billion in market value in a single day—a record for the largest single-day market cap loss by a U.S. company. The Nasdaq fell 3.1%, and the S&P 500 dropped 1.5%. Broadcom fell 17%, and ASML dropped 7%.

Investors distilled DeepSeek into a super-simple logic: If Chinese companies can create equivalent AI models using cheaper, older chips and fewer resources, then the tens of billions of dollars invested in AI infrastructure by U.S. tech giants might be wasted.

Now is the time to compare two very similar yet significantly different market panics.

Cowork Panic May Be More Lasting Than DeepSeek Panic

As the editor-in-chief who tracked the events through Hangtongshe's "Daily AIGC Briefing," I vividly recall that DeepSeek gained widespread attention from AI professionals as early as late 2024. I even wrote an article titled "Why DeepSeek Is the Kimi of 2025" (which now seems hilarious in hindsight...).

The chain reaction in the capital markets had several key intermediaries: Andrew Karpathy's continuous endorsements and a 30-minute CNBC special on January 24 were widely cited as sources of interpretation.

The moment Cowork's impact spread from the AI community to the financial sector came with Wharton professor Ethan Mollick's demonstration of "fully automated due diligence" and its connection to Sequoia Capital's "Service-as-Software" memo from a year earlier.

Both panics shared similarities, such as analysts believing the market reaction was excessive. Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei called the market reaction after DeepSeek "puzzling" on January 29 last year. This time, even Jensen Huang, who was previously pressured to comment, proactively stated that the sell-off in software stocks was "the most illogical thing in the world."

However, I believe that beyond these similarities, the current Cowork panic may be more lasting than the DeepSeek panic.

DeepSeek's panic originated from a Chinese open-source model company, while Cowork's panic comes from a U.S. closed-source model company. The former replicated existing achievements at lower costs, while the latter achieved a previously non-existent outcome or use case. Simply put, the challenges are "from 1 to n" versus "from 0 to 1." While both can disrupt, proving or disproving the "from 0 to 1" challenge requires more time and cases than "from 1 to n."

Moreover, the two shocks are so similar that people cannot help but compare them immediately. When they realize that comparison does not ease their concerns and that it is not just a false alarm, the panic becomes more pronounced and prolonged.

In fact, the Cowork panic has already lasted longer than the DeepSeek panic.

The DeepSeek panic was largely digested within a day, with NVIDIA rebounding 9% the next day. By October 2025, NVIDIA briefly surpassed a $5 trillion market cap. In contrast, the software stock sell-off triggered by Cowork panic lasted a full week, spreading from Wall Street to IT service stocks in London, Tokyo, and India, and intensified further after the release of the Opus 4.6 model. As of this writing, there is no sign of relief.

Jevons' Paradox Fails in the Software SaaS Sector

After the DeepSeek panic, Jevons' Paradox became a hot topic in the tech circle. Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella was among the earliest to popularize the term, stating, "As AI becomes more efficient and accessible, we will see a surge in its usage."

The original meaning of Jevons' Paradox is that when the efficiency of a resource's use increases, its total consumption rises because lower unit costs stimulate greater demand. This theory applies to AI models and computing power, as cheaper models indeed lead to more usage. It even applies to Cowork, as simpler interactions lower the barrier to use, resulting in more usage.

However, it does not directly imply that traditional SaaS software companies will benefit—in fact, the opposite may be true.

First, software pricing models are inherently fragile. Traditional software relies on two mainstream pricing models: usage-based and per-seat billing. The per-seat model is a buyout system—once a person pays the fee for the month, they can use it however they want. When AI-driven efficiency gains lead to layoffs or downsizing—whether or not AI directly causes them—the number of seats declines, reducing revenue from per-seat billing.

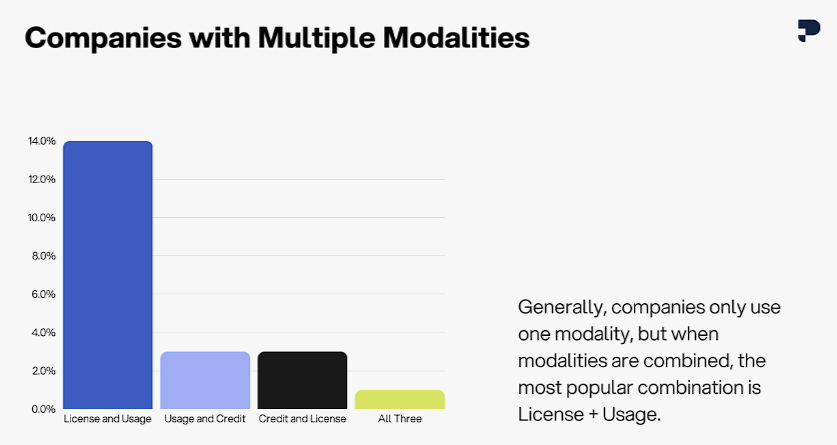

SaaS companies have had to abandon buyout models and transition to usage-based pricing.

The PricingSaaS 500 index tracks over 1,800 price changes. It notes that in 2025, the top 500 SaaS companies averaged 3.6 pricing changes per company annually. Among the 500 companies tracked by PricingSaaS, 79 now offer point-based pricing (i.e., usage-based billing), a 126% year-over-year increase. Figma, HubSpot, Salesforce, Monday, and Airtable all adopted point systems in 2025.

Salesforce learned this the hard way. They launched Agentforce at $2 per conversation, but support teams calculated that five agents would cost over $20,000 per month, forcing a switch to point-based billing within months. Companies struggling with computing costs adopted smaller billing units: N8N charges per workflow execution, with 50 steps costing the same as 2 steps. However, Zapier charges per task, billing each step individually.

Ultimately, a hybrid model of base monthly fees plus Excessive purchase of cards (excess point purchases) works best. Such products reported the highest median growth rate of 21%, outperforming pure subscription and pure usage-based products. 46% of SaaS companies combine subscriptions with variable fees, and 59% expect usage-based pricing to increase revenue share by 2026, up from 18% in 2023.

Second, the logic of raising prices after adding AI to traditional software faces strong resistance. CNBC reported that some management teams refused to pay $30 per month per employee for 365 Copilot, unsure of its benefits. Last October, Australian regulators sued Microsoft for "forced bundling of AI" and hiding lower-priced options, inducing subscribers to believe that the 45% more expensive AI version was the only renewal choice while deliberately concealing the lower-priced "Classic" version without Copilot on the secondary cancellation page. Microsoft ultimately announced in December last year that it would raise prices by $3 per person per month for all commercial suites starting July this year and mandate the inclusion of basic AI features, triggering customer dissatisfaction.

Third, traditional software companies' AI transformations are often clumsy and inefficient. Many traditional software giants attempt to embed AI into existing products but fundamentally do not understand how AI synergizes with their accumulated datasets. The result is often a pileup of features that no one uses. Meanwhile, a wave of startups creating native AI agents from scratch in traditional software domains are securing substantial funding.

For example, Harvey in the legal AI space raised $300 million in two funding rounds in 2025, reaching a $5 billion valuation; enterprise search AI company Glean reached a $7.25 billion valuation. According to Menlo Ventures, the AI application layer accounted for over half of enterprise AI spending ($19 billion) in 2025, with AI-native startups generating nearly twice the revenue of traditional software vendors. The median annual growth rate for AI-native startups reached 100%, compared to just 23% for traditional SaaS companies—a 4.3x gap.

Enterprise Self-Built Tools and Beyond

Another trend threatening traditional software is the rise of Vibe Coding. As I pointed out in Hangtongshe's article "Generating Apps with One AI Sentence: Lofty Ideals, Harsh Realities," if Vibe Coding matures, individuals will prefer building their own tools rather than purchasing third-party ones. The same logic applies to enterprises.

Enterprise clients may stick with SaaS products long-term rather than chasing new options, possibly due to the hassle of customization. If Vibe Coding makes "speaking laws into existence" a reality, the situation could change entirely. In fact, when new technologies are simple enough and deployment costs low enough, enterprises adapt quickly.

After social networks became popular, many corporate websites reduced update frequencies; after Threads launched, companies quickly added it to their social media Operation List (operation lists) alongside X/Twitter. Even the widespread adoption of DeepSeek by enterprises in early 2025 is an example—as long as the barrier is low, companies embrace change proactively.

Even before practical applications of Vibe Coding emerge, its predecessors—low-code/no-code products—have already attempted to enable enterprise employees to program individually and solve real-world production issues. However, rule-based low-code systems heavily dependent on platform runtime environments became the first casualties of AI model advancements, as exemplified by Lanma Tech, which announced its closure in February last year.

For traditional software and service companies impacted by AI, a discernible "three-step path to extinction" exists. Let's use Chegg as an example.

Step 1: Deny AI's effectiveness. In 2022, Chegg employees proposed developing AI tools to automate answers, but management rejected the idea. After ChatGPT's release, Chegg executives dismissed AI as "inaccurate" and not a threat.

Step 2: Announce AI integration or transformation, but with poor results. Chegg later partnered with OpenAI to launch "CheggMate," attempting to combine its database of 120 million expert answers with AI. However, students were unwilling to pay—ChatGPT was "good enough" and free.

Step 3: Extinction. Chegg's subscriber base plummeted from a 2022 peak of 5.3 million to 3.2 million in 2025. Its stock price collapsed 99% from its 2021 high of $113, with market cap shrinking from $14.7 billion to about $156 million. In 2025, the company laid off 22% and then 45% of its workforce, with over half of employees let go within six months.

Currently, for traditional legal tech companies, financial data firms, and even consulting firms, the Cowork panic is still in the first stage, with many "scholars defending the status quo" arguing that AI hallucinations cannot be fully eliminated and are unusable.

However, enterprises' demand for software lies in digitizing and informationizing certain workflows. Previously, employees had to adapt, and software companies developed on-site—all involving others simulating and listening to your needs, never as clear as your own understanding, with massive costs wasted on communication.

Thus, when enterprise employees know that a simple script (even without large models, just a Python script) can solve the problem, it may mark the beginning of SaaS's true collapse.

Going forward, the traditional software industry's greatest value may lie in serving clients' highly customized, non-standard needs—the "dirty work" that general AI products avoid and that clients cannot Vibe out themselves. However, this "large model construction crew" role, described as unsexy as early as 2023, is hardly a compelling business model.

For models, the focus must remain on aggressively improving programming capabilities until the "hallucination fortress" is dismantled, reaching a tipping point where minor inaccuracies no longer matter. Then, "less structure, more intelligence" will prevail, sweeping away everything in its path.