Tech Giants' Spring Festival AI Dilemma: Is Cash the Only Way Forward?

![]() 02/09 2026

02/09 2026

![]() 412

412

By He Ying

Edited by Zhang Xiao

This Spring Festival, tech behemoths are resorting to time-honored tactics to ease their cutting-edge concerns.

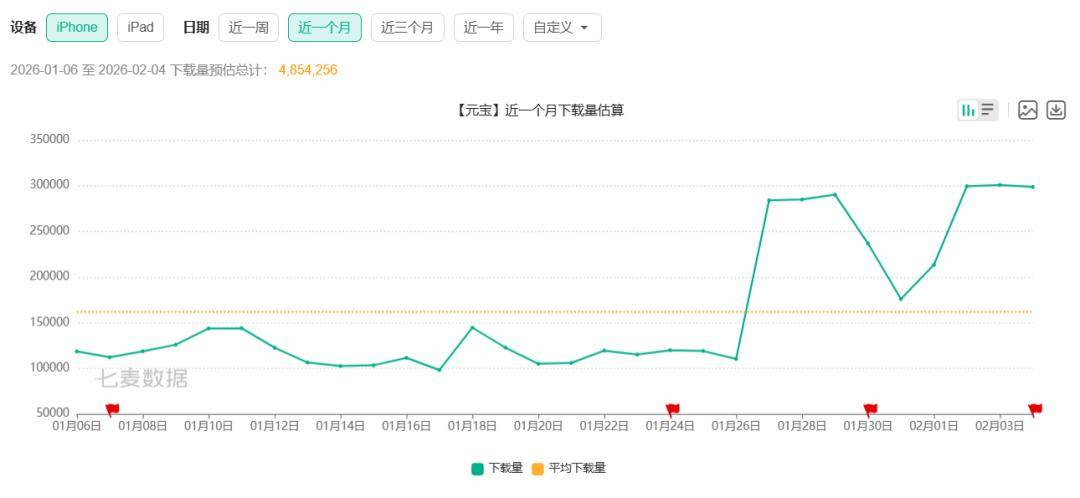

On the evening of January 31st, Tencent Yuanbao rolled out a staggering RMB 1 billion cash red packet giveaway. The result? A surge in daily active users (DAU), propelling it to the top of the App Store China free chart by the afternoon of February 1st.

Pony Ma, in response, articulated at an internal staff meeting his hope that this move could mirror the watershed moment WeChat red packets achieved 11 years prior.

Several classic market reactions quickly emerged around this round of Yuanbao red packets.

Some users enthusiastically shared them; others waited to gauge the rewards before deciding to participate; and a third faction, primarily AI application power users, pondered: When would Zhang Xiaolong ban Yuanbao links? After all, this tactic seemed to encapsulate all the keywords explicitly barred by WeChat over the years—incentivized downloads, viral sharing, and "cut one knife"-style user acquisition...

Yet, judging by the current outcomes, Yuanbao appears to have replicated more of a "Pinduoduo moment," with the excitement proving fleeting.

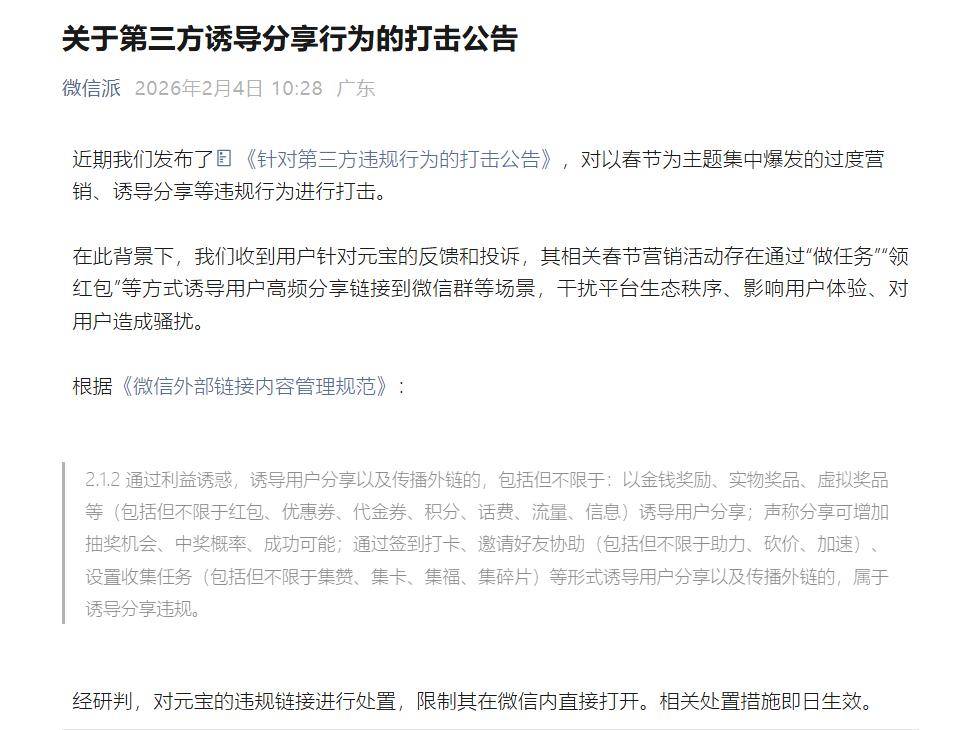

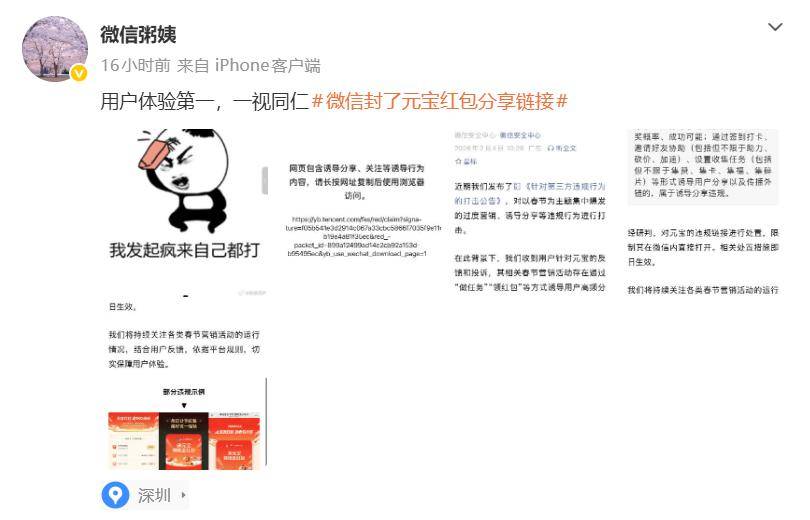

On February 4th, numerous users found that Yuanbao red packet links in WeChat groups triggered system warnings about "inducive sharing content," necessitating copying to a browser for access.

Image via WeChat Official Account 'WeChat Pie'

Image via WeChat Official Account 'WeChat Pie'

Currently, Yuanbao's red packet sharing has transitioned to "password red packets."

Great, now it's even more reminiscent of Pinduoduo.

This scenario feels all too familiar. Subsidies, user acquisition, and cash burn—virtually every major product from Chinese tech giants over the past decade has undergone similar phases: at some juncture, being forcefully pushed onto everyone's phones via red packets, subsidies, or some nationwide craze.

The distinction this time is that AI takes center stage.

This isn't counterintuitive. The Spring Festival represents the pinnacle time of year to "exchange money for behavior." The phenomenal success of WeChat red packets is still celebrated and emulated across the industry, including by Tencent itself.

Yuanbao isn't alone in this endeavor. Almost simultaneously, Baidu and Alibaba also launched red packet campaigns for their respective AI applications. The approaches, scale, and pacing varied, but the actions were highly synchronized.

Acquiring users is swift; cultivating habits takes significantly longer. Hence, this wave of high-profile AI red packets feels more like an initial traffic grab than a signal of any application's maturity.

01

Three Tech Giants, Three Distinct "User Acquisition" Strategies

Among this round of AI red packets, Tencent's Yuanbao has been the most prominent thus far.

Yuanbao made little attempt to conceal its intentions, with task paths condensed to be extremely brief: chatting with AI, generating images or videos, and earning lottery draws; referral rules were equally straightforward—share the link, and if the recipient downloads the app, it counts as a success.

Image via Yuanbao App

Image via Yuanbao App

In practice, this represents an extremely standard "user acquisition" model—I forwarded to three friends, secured three Yuanbao downloads, and ultimately received a red packet of just RMB 0.28. The earnings from forwarding pale in comparison to even a minor loss in gold investments.

Under this design, users barely need to grasp the product's value to complete a full usage cycle. The final payout amount is inconsequential; what matters is that users have helped Yuanbao achieve its most critical objective.

This approach addresses the most fundamental issue: getting installed on as many phones as possible. Whether users remain engaged afterward isn't the priority at this stage.

Judging by the results, this design indeed yielded rapid success post-launch. Yuanbao's swift ascent up the charts more closely resembled a validation of Tencent's social traffic conversion capabilities than an assessment of AI product strength. In a sense, it continued strategies Tencent has repeatedly employed for new product launches in recent years.

Image via Qimai Data

Image via Qimai Data

Some users told TI Chao that when Yuanmeng Star initially launched its public beta two years ago, it utilized identical tactics during the Spring Festival: register and log in to claim WeChat red packets, in-game "red packet rain," etc.

In contrast, Baidu Wenxin's red packet design leans more towards "operational engagement."

Rather than betting everything on one-time user acquisition, Baidu dispersed red packets across multiple usage scenarios: users unlock rewards gradually through content participation, card collecting, passwords, etc., over a 46-day cycle, amplified by the high-exposure Spring Festival Gala to repeatedly draw users back to Wenxin Assistant.

Image via WeChat Official Account '@Baidu Wenxin'

Image via WeChat Official Account '@Baidu Wenxin'

The core objective here isn't one-time conversion but extending usage pathways. Baidu hopes users will stay longer and return more frequently, embedding the AI assistant into daily search and content routines. Red packets serve as tools to amplify interaction density and prolong user engagement.

Alibaba's Qianwen appears more restrained. While also launching a red packet campaign worth hundreds of millions, available information suggests its focus lies less on single-app virality and more on integrating with existing ecosystems like Alipay and Taobao—more about "not missing out because competitors did it." This strategy doesn't pursue short-term chart rankings but ensures basic visibility for AI applications during this peak traffic period.

Viewing all three companies' actions together makes it difficult to judge effectiveness by a single metric. More accurately, they're exchanging red packets for what each lacks at their current stage: Tencent seeks downloads and DAU, Baidu desires engagement and interaction, and Alibaba aims for ecosystem presence.

This comparison also underscores Doubao's notable absence.

Over the past two years, the "super gateway" position for domestic AI applications has shifted repeatedly, with Kimi, DeepSeek, and Qianwen all gaining attention at different stages. However, Doubao consistently leads in consumer reach. By late 2025, it had become China's first AI product with over 100 million daily active users.

Image via QuestMobile

Image via QuestMobile

For an application that has already achieved significant user penetration, participating in another round of red packet campaigns focused on user acquisition holds little meaning. The challenge lies in increasing usage depth, not generating more downloads.

From this perspective, the differing goals explain why this wave of AI red packets feels both concentrated and fragmented. It resembles a collective trial run—seizing the Spring Festival window to push their AI to users, with no clear answers yet on retention.

02

Why AI? Why Red Packets?

If AI had already found stable high-frequency usage scenarios, this round of red packets wouldn't be necessary.

The reality is that while AI continues breaking technical barriers, user adoption remains hesitant.

Over the past two years, AI has been framed in a relatively "upward" narrative. Product launches and financial reports emphasize model capabilities, technical routes, and long-term potential, positioning AI as the next platform-level opportunity requiring early positioning. Yet when competition reaches consumer markets, questions become specific: which AI gets downloaded by more ordinary users? Which gets opened more frequently?

From a product standpoint, AI is undoubtedly a tool. But tools don't automatically equate to high frequency. Mature tools see repeated use because clear triggers exist: when to use them, why to use them, and what inconveniences arise from not using them.

In contrast, AI's capabilities are general-purpose, while usage scenarios remain fragmented. For most users, AI doesn't correspond to a specific moment but feels like an always-available yet non-urgent option.

This directly impacts user behavior. AI is easily tried but hard to rely on. Downloads and first-time use often stem from curiosity, but without clear triggers, forming habitual usage proves difficult. Consequently, while technical capabilities are validated, usage frequency remains unstable.

This explains why many AI applications linger at the "usable" stage without naturally progressing to "commonly used." They lack neither capabilities nor features but a recurring reason to use them.

Image via AI Product Rankings

Image via AI Product Rankings

When product design cannot immediately solve this issue, growth strategies take precedence. Handing out money becomes the most certain and direct solution.

During stages where model capabilities converge and scenarios remain immature, securing phone installations, entering daily routines, and achieving usage become more critical than explaining product value.

At this stage, subsidies aim less at persuading users than bypassing comprehension costs to directly generate recordable usage behaviors. Red packets don't solve retention or guarantee habit formation, but they reliably produce downloads, opens, and interactions—compensating for the product's lack of clear triggers.

The Spring Festival represents a rare window when users' daily rhythms are interrupted, online entertainment and social sharing density rises, and new products more easily insert into existing routines. Meanwhile, red packets' strong stimulus aligns perfectly with festive contexts, synchronizing sharing and action within a short period.

However, this approach merely delays problem exposure. By using the most certain methods to lower barriers and acquire users first, then attempting to supply usage reasons later, the burn-money subsidy tactics favored by tech giants fail to address a core question:

When external incentives disappear, does the product already provide compelling reasons for repeated use? If not, this round of user acquisition may yield limited actual growth.

03

When Red Packets Become Industry Standard

Discussing similar strategies inevitably recalls WeChat and Alipay.

In China's internet growth history, red packets are hardly new. Whether WeChat's "Shake" feature or Alipay's "Collect Five Blessings," both created nationwide engagement during the Spring Festival. Looking back, their value lay less in money distribution itself than compressing product education into nearly effortless participation.

But these successes weren't accidental.

"Shake" solved first-time binding and usage of a payment tool, after which users naturally progressed to transfers, payments, and collections. "Collect Five Blessings" boosted Spring Festival activity and participation, with Alipay already embedded in daily life as infrastructure. Red packets merely lit the fuse; what retained users were subsequent usage scenarios.

This reveals an implicit prerequisite for red packet strategies to work: after opening, a nearly inevitable next step must exist.

Because this pathway has proven effective historically, it gets reused repeatedly. When a product still needs DAU, red packets represent a costly but highly certain launch method. They never solve long-term problems but reliably generate scaled behavior quickly.

The issue arises when this approach stops being an individual product's choice and becomes an industry-wide standard solution. Then it stops being a marketing campaign and transforms into a replicable behavioral model. Baidu Wenxin, Alibaba Qianwen, and even more AI applications yet to enter the fray could all adopt similar tactics simultaneously.

When such behaviors amplify across social chains, platforms face not compliance issues for individual campaigns but sustained erosion of overall order and user experience. For WeChat, this becomes less about "supporting in-house products" and more about setting boundaries for entire behavioral categories.

Against this backdrop, WeChat's restrictions on Yuanbao red packet links become understandable.

Tencent responded internally that Yuanbao's Spring Festival red packets followed a "no-threshold claiming" logic, requiring no assists or card collections—fundamentally different from prohibited inducive sharing models and thus permissible as user benefits.

Meanwhile, WeChat Pie and WeChat's PR director "WeChat Zhou Yi" published articles stating, "User experience comes first, no exceptions," accompanied by a meme reading, "When I go crazy, I even hit myself."

Image via Sina Weibo

Image via Sina Weibo

This resembles a "left brain vs. right brain" conflict within the same company, but from a platform perspective, it represents proactive governance. In other words, this isn't an uncontrolled "emergency brake."

After Yuanbao captured initial attention and fully demonstrated its tactics to the market, restrictions arrived logically—not to negate the pathway but to prevent infinite replication.

04

Final Thoughts

Viewed over a longer timeline, the true message of this AI red packet wave lies less in individual campaign effectiveness and more in a clearer industry signal: when nearly all tech giants compete for attention using identical methods, superior solutions haven't emerged yet.

Throwing money itself shouldn't be mythologized. It represents a mature, old-fashioned, and highly controllable tactic—using cash to secure certain behaviors during high-uncertainty phases aligns perfectly with what tech giants know best. Yet when growth must rely on such methods, it suggests organic diffusion and spontaneous growth can no longer be trusted.

This issue is not confined to a single company; rather, it is a challenge confronting the entire industry.

Technical advancements in AI have not come to a standstill. However, at the user end, a compelling, stable, and frequently applicable reason for utilizing AI has yet to be identified. Until this fundamental problem is effectively tackled, any growth attained through financial investment will merely represent a temporary accomplishment, rather than a sustainable competitive edge.

This is exactly why platforms are starting to reassess their operational boundaries. When a particular growth strategy holds the potential for widespread adoption, it transcends being a mere market decision for businesses and transforms into a systemic issue that demands attention. The imposition of restrictions does not dismiss the validity of this strategy but rather recognizes that its broader impacts now necessitate regulation.

From this vantage point, the current wave of AI-driven promotional giveaways, such as red envelopes, appears more akin to an initial phase of user acquisition rather than an indication of product maturity. These efforts are geared towards attracting users, rather than ensuring their long-term retention.

The fact that major industry players are compelled to invest heavily suggests that the truly pivotal factors for success have yet to surface.