"Collective de-low-pricing: Merchants regain bargaining chips, platform value to be reassessed

![]() 08/06 2024

08/06 2024

![]() 718

718

Recently, both Taobao and Douyin have downplayed the low-pricing strategy. For instance, CEO Wu Yongming of Taobao Group has internally clarified that GMV should be the primary indicator, with a return to shelf e-commerce, shifting the focus of assessment to GMV (Gross Merchandise Volume) and AAC (Annual Active Consumers), rather than solely pursuing order volume driven by low prices.

Douyin E-commerce President Wei Wenwen also stated in an internal meeting that "Douyin E-commerce's pricing power is not simply about pursuing absolute low prices." Latest news indicates that Pinduoduo has also started to prioritize GMV as its primary goal (even at the expense of monetization rate).

For a long time, the market has regarded "low price as the core competitiveness of retail": low prices can attract new users, leading to rapid growth, increased market share, and a positive cycle. Now, top companies are adjusting their strategies, reducing the emphasis on low prices in favor of GMV, leaving many puzzled and uncertain.

Is this, as some argue, because "platforms have no choice but to prioritize profits," or are there other factors at play? With these questions in mind, we wrote this article, with the following core viewpoints:

Firstly, both macro and micro perspectives validate that pricing power in retail is shifting towards merchants, making price control by platforms less feasible.

Secondly, faced with new industry challenges, platforms choosing to re-embrace GMV and de-emphasize low-price orders is entirely necessary. At the same time, the relationship between platforms and merchants will undergo new negotiations.

Thirdly, new challenges bring new strategies, and the industry remains dynamic, with industry value poised for reassessment.

New Industry Trends: Pricing Power Gradually Shifts to Merchants

We first use economic principles to briefly explain the necessity of the previous low-pricing strategy:

1) In recent years, China's macroeconomy has been in a destocking cycle, requiring enterprises to rapidly increase volume through low prices to improve cash flow.

2) At the micro level, retail platforms can use low prices to boost marginal effects (even though consumption is sluggish, price-sensitive users are still motivated by "low prices"), which explains why marketing tactics like the Hundred Billion Subsidy Program have become increasingly mainstream.

In summary, whether macro or micro, low prices have their rationality and necessity, and platforms that decisively adopt low-price advantages can naturally gain a larger market share (e.g., the booming live streaming e-commerce industry in recent years).

So why are these companies now changing this strategy?

A platform's core competitiveness is ultimately reflected in GMV, leading to the formula:

GMV = Sales Quantity * Unit Price.

As previously analyzed, if a platform can maintain a competitive price advantage, it can attract more demand (a surge in sales quantity), ultimately driving greater GMV growth. The leverage effect of low prices is evident here.

Now that retail enterprises are abandoning this mindset, we instinctively think that the low-price advantage may no longer translate into increased demand.

Next, let's validate this hypothesis.

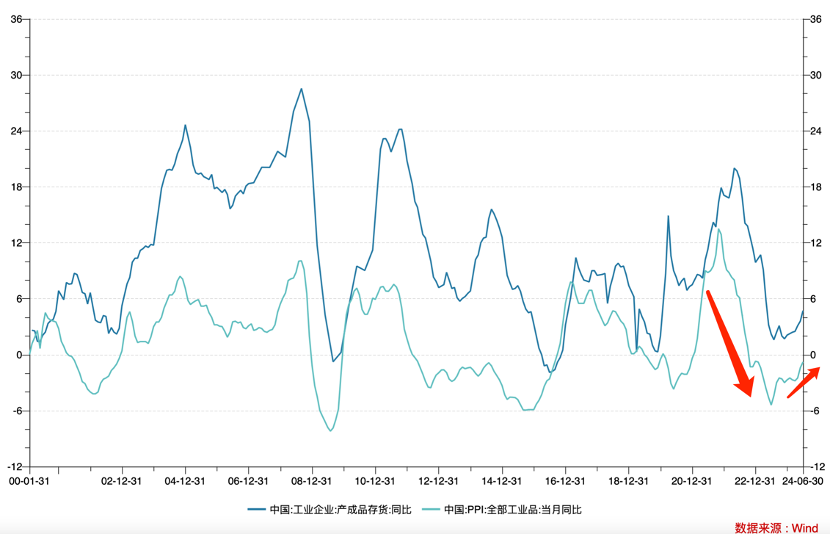

The economics community has long used changes in industrial inventories to deduce economic cycles. Based on the year-on-year growth rates of finished product inventories of Chinese industrial enterprises and the monthly year-on-year growth rate of PPI for all industrial products, inventory cycles are divided into four stages:

Active Restocking Phase: PPI Rising + Inventories Rising

Passive Restocking Phase: PPI Falling + Inventories Rising

Active Destocking Phase: PPI Falling + Inventories Falling

Passive Destocking Phase: PPI Rising + Inventories Falling

Since 2021, China has undergone a significant destocking process, with both PPI and inventories declining year-on-year. However, since 2024, both lines in the chart above have shown signs of bottoming out, with both trending upwards in the second quarter.

Admittedly, domestic demand remains weak, and both CPI and PPI are still low. It's unclear whether these trends are temporary or long-term, but based on historical experience, there may not be much room for further deterioration.

When the macroeconomy enters an active restocking phase, it means that most industries have completed the process of survival of the fittest, and the surviving enterprises begin to regain pricing power, restocking as they become more optimistic about the future.

Assuming the above trends are true, in the game between platforms and enterprises, the latter will increasingly gain pricing power, while platforms' ability to control prices will weaken.

If price reductions are less feasible at the macro level, what about the micro level?

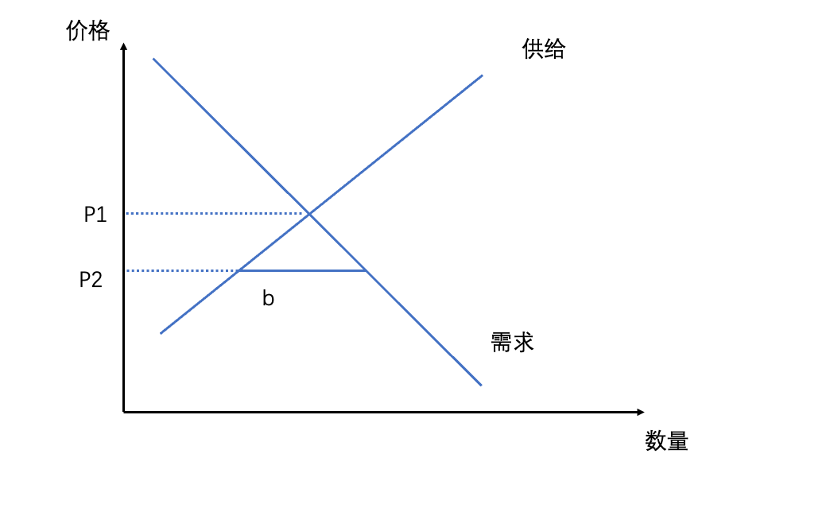

We all know that supply and demand determine prices. Two factors determine the fair value of a product as P1. If a platform forcibly lowers the price to P2, and the supply-demand relationship does not significantly change in the short term, low prices will lead to reduced supply, with segment b's demand going unfulfilled (this is why merchants have recently resorted to bait-and-switch tactics in response to low prices, essentially reducing supply).

As mentioned earlier, when aggregate demand is still robust, price reductions can lead to an expansion of total demand, and merchants can still achieve economies of scale, absorbing the cost of price reductions. Conversely, when aggregate demand remains sluggish, price reductions lead to reduced supply (merchants opting not to sell), which can actually inhibit sales.

Returning to the formula "GMV = Sales Quantity * Unit Price," currently:

1) At the macro level, it is increasingly difficult for platforms to control prices, and pricing power is increasingly shifting to merchants.

2) At the micro level, reducing the unit price does not lead to a surge in quantity, but instead drags down GMV growth.

Whether it's Taobao, Douyin, or Pinduoduo, since they cannot achieve absolute low prices (even if the cost is prohibitively high), it's better to actively embrace the new changes.

Platform Value to be Reassessed

In the previous analysis, we basically explained the main reasons for the industry's shift away from low prices. How will this change the industry landscape?

According to public information, Guosen Securities has outlined the main development trajectory of China's e-commerce, which aligns with our previous logic.

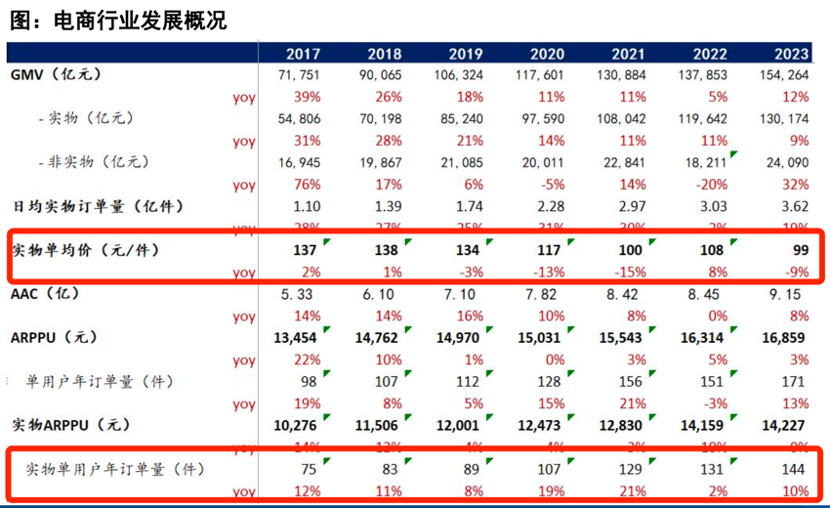

2020 marked a turning point for China's e-commerce industry. Before then, the industry grew on a dual-engine model (annual user orders and average unit price), presenting a picture of both volume and price increasing. Subsequently, user orders continued to grow, while the average unit price began to decline sharply.

While this is partially related to the accelerated online transaction of low-priced goods during the pandemic, we must also recognize that merchants began to abandon pricing power during that economic climate, transitioning from pursuing profits to simply surviving.

Taking 2020 as a dividing line, the most successful enterprises before then were JD.com and Taobao, followed by Douyin, Kuaishou, and Pinduoduo as pillars of retail.

Many are curious: with the external environment having changed, will the industry landscape shift accordingly?

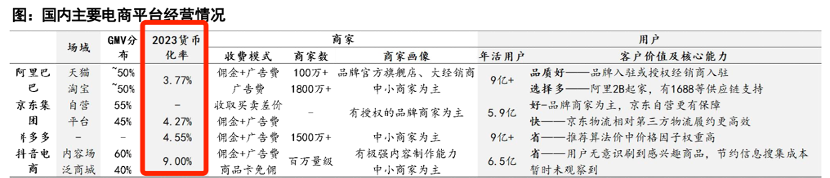

The above chart, from Guosen Securities, shows the monetization rates of representative e-commerce enterprises in 2023. There has long been a bias in the market that:

Platforms with low monetization rates are the most popular among merchants, while those with high monetization rates are unpopular due to the heavy burden on merchants.

In 2023, Douyin E-commerce's monetization rate soared to 9%, and Pinduoduo's exceeded 4.5%, yet these two platforms happen to be the fastest-growing in recent years. Using monetization rate alone to judge platform appeal is not objective and must consider "growth potential." When merchants are eager to destock, they overlook monetization rates. The growth rates of the above two platforms are evident, and merchants are willing to spend more on these platforms.

However, once merchants complete destocking and regain pricing power, they will be more rational in selecting platforms:

1) Platforms with low monetization rates will gain increased importance.

As merchants shift their business philosophy from "volume" to "profit," monetization rate becomes a crucial metric. At this point, Taobao's low monetization rate becomes significant again.

Meanwhile, other platforms will also reduce their monetization rates to maintain competitive advantage, such as Pinduoduo's recent intention to lower its monetization rate to support GMV growth.

2) Whether the platform can provide merchants with room for premium pricing.

When the market was focused on volume, high-premium platforms struggled (like JD.com), even top merchants had to humble themselves in live streams, and consumers shunned high-priced platforms.

As the market shifts, merchants will select platforms based on their ability to command higher premiums. JD.com and Tmall, which attract more middle-class and above consumers, will regain importance, testing the effectiveness of Pinduoduo's Hundred Billion Subsidy Program for brand merchants.

Earlier, media reports suggested that Ali Group was returning to Taobao (at Ma Yun's suggestion), leading many to believe the platform was determined to pursue a low-price strategy and abandon consumption upgrades. In retrospect, this view is obviously biased.

Before this, driven by profitability and catering to consumption upgrades, Tmall became the priority for Ali Group's e-commerce, while Taobao, as the origin platform, became increasingly marginalized. The result was that when the external environment changed, Ali Group lost its footing in e-commerce and had to hastily launch Taobao Deals, missing the golden opportunity for reform.

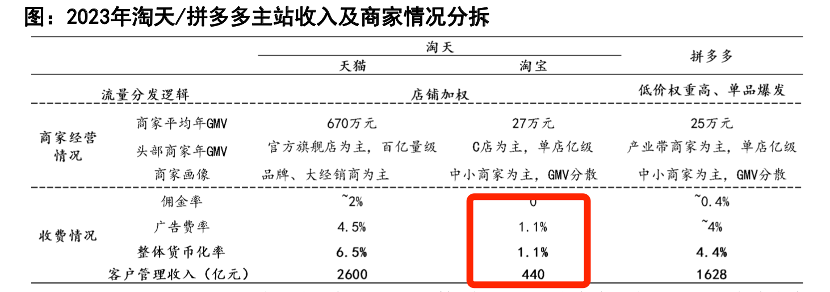

This is directly reflected in Taobao's monetization rate.

Broadly speaking, Taobao and Pinduoduo stores are quite similar, but the latter's monetization rate is four times that of the former (emphasis again that merchants didn't care about costs at the time). Taobao was essentially begging with a golden bowl in hand.

Returning to Taobao and treating Taobao sellers equally, providing them with more marketing tools, can not only bring Taobao sellers back and invigorate the e-commerce ecosystem but also tap into the platform's profitability. For instance, Taobao Group is currently beta-testing site-wide promotion (merchants select products and set daily spending budgets in the system, which then runs automatically), considering its monetization rate is still far lower than similar platforms, indicating significant commercial potential.

Returning to Taobao does not mean Tmall is no longer important; on the contrary, in this new cycle, Tmall's value will be reconfirmed.

The retail market may seem simple but is actually ever-changing, with external environmental changes, consumer habits, and industrial adjustments all truthfully reflected in the retail market. This necessitates a dynamic perspective on the industry. With various undercurrents swirling, the retail industry is on the eve of a new round of transformation, and a new interest structure is brewing. Now that major platforms have let go of their past obsessions to embrace change, we must remember: low prices will not be the permanent theme, and merchants will not always be passive players.