Auto manufacturer naming miscellany

![]() 08/06 2024

08/06 2024

![]() 606

606

The cultural matrix of China is not limited to Shanhaijing, and brand culture should also be reflected in every touch point with consumers.

Recently, two things have been quite popular. In this sweltering summer, traditional automakers are scrambling to find their Altay, while new players prefer to rely on PPTs in meeting rooms for promotion, and they invariably choose technology.

With all sorts of technology days dazzling, what is more challenging in these dull and dry technical explanations is actually the enterprise's ability to coin words. Coming up with a fancy and impressive name is more useful than a hundred pages of broken-down PPT lessons.

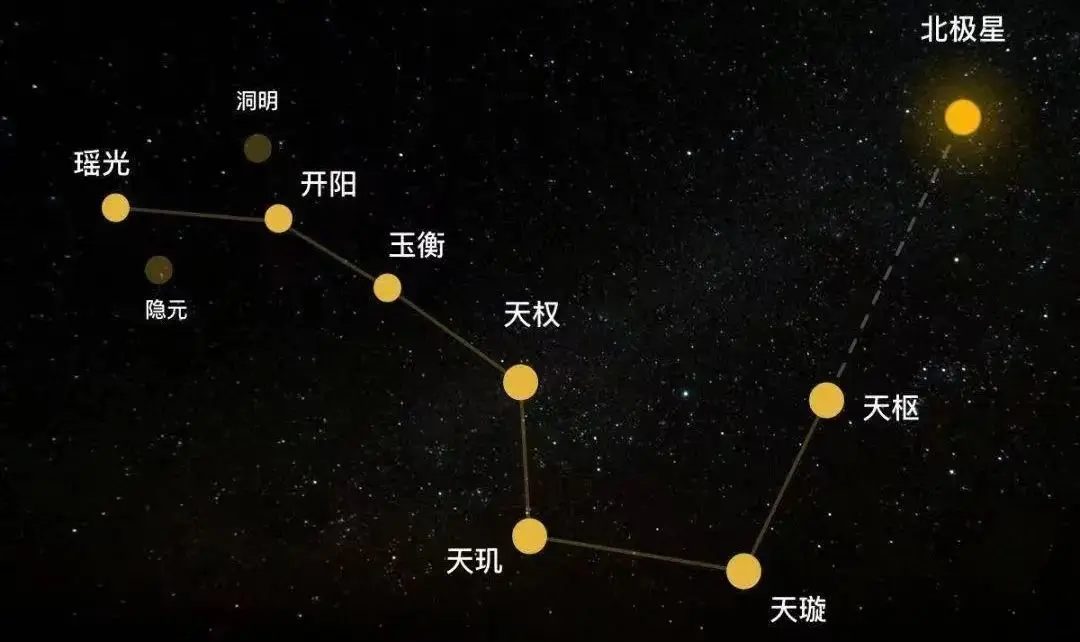

NIO's Tianshu OS, Xpeng's AI Tianji XOS, Chery's Xingtu Yaoguang Lab... In the process of competing with technology, the Big Dipper undoubtedly got caught in the crossfire. It has to be said that if automakers continue to compete like this, the Big Dipper will soon run out of stars.

Here, I would like to take this opportunity to discuss the topic of naming with you all.

Naming automakers is actually quite similar to naming people.

Each generation has its own mission, label, and unique suffix. If people used to be named according to their clan's generation names to remember their family and pass on their bloodline, then during the early days of the People's Republic of China, names more often served as a chronicle of significant events.

From "Jianguo" (Founding of the Nation), "Heping" (Peace), to "Yuanchao" (Supporting North Korea), "Yuejin" (Leap Forward), "Weidong" (Guarding the East), and later names like Wang Wei, Zhang Qiang, Li Ming, now names with the character "xuan" (meaning elegant carriage) from the Book of Songs are all the rage. These names, imbued with the mark of their times, vividly illustrate the rise and fall of one era after another.

Few brands can break free from the limitations of history and come up with a name that stands out from the majority of businesses today. If any do, they unfortunately tend to die out early and fade into obscurity.

In the early days of China's automotive industry, automaker names were also imbued with the color of their time: Red Flag, Dongfeng, Huanghe, Changjiang, Beijing, Shanghai... This is probably because the automotive industry developed with the concerted efforts of the entire nation, reflected in its names that are intimately connected to the country's heritage.

After the market economy reforms, a new wave of automakers emerged, and their names also carried certain hallmarks of their time: Great Wall, Geely, BYD. Except for Great Wall, most of them first had a trendy foreign name before translating it back. Nowadays, cultural self-confidence is valued, but in those days, a touch of foreign flavor was still considered essential for prestige.

Of course, these names were later deemed tacky by outsiders, which is partly related to psychology. Whether domestic or foreign, there is often a case of native language shyness.

We feel a sense of shyness towards our familiar native language but a vague sense of sophistication towards unfamiliar foreign languages. For instance, Geely is quite common, but GEELY sounds more premium.

Many fancy foreign brands that seem sophisticated to consumers also become instantly tacky when translated directly. For example, Head & Shoulders means "heads and shoulders" in English, straightforwardly indicating that their products are for shampooing heads and shoulders. Johnson & Johnson, to foreigners, probably just sounds like "Zhang Brothers."

BMW stands for "Bayerische Motoren Werke," meaning Bavarian Motor Works in German. Ferrari means "blacksmith" in Italian. A series of brands named after their founders often have no direct meaning, such as Mercedes-Benz, Ford, Toyota, Honda, and so on.

Using people's names for brand names seems harmonious in foreign brands but may appear very tacky in a Chinese context. For instance, this new wave of automakers emerging has several aiming to become centenary enterprises and named after their founders.

Li Xiang used a homophonic pun to create Lixiang Auto, with the brand logo being the Pinyin "LI." NIO seems like a premium name, homophonous with "future," but essentially, it is also homophonous with Li Bin's English name, William. Of course, this is rarely mentioned, but if you repeat "William" a few times, you might find the NIO vibe.

He Xiaopeng is quite straightforward; since his name is He Xiaopeng, his car company is called Xpeng Motors. It was agreed to use personal names, so why did Li Xiang and Li Bin resort to homophones? Xpeng Motors has since become the most criticized brand name among the new players.

These companies share some commonalities in naming. At least they have moved away from the once prevalent mindset of worshipping foreign things and started to believe that China's automotive industry is on par with foreign ones. If foreign brands can use their founders' names, why can't Chinese brands?

In fact, this rhetorical question still subtly reveals the inferiority complex of worshipping foreign things. Genuine self-confidence doesn't care about what others do; those with a strong inner self often focus on doing their own thing well. Among this new wave of players, there are many other eclectic names, many of which have disappeared along with the bankruptcy of their companies.

Returning to those companies that cleverly borrowed the Big Dipper's stars to name their technological innovations, they are also trying to ride the wave of the rise of a great power, aspiring to become significant technological achievements for the nation whenever technology is involved.

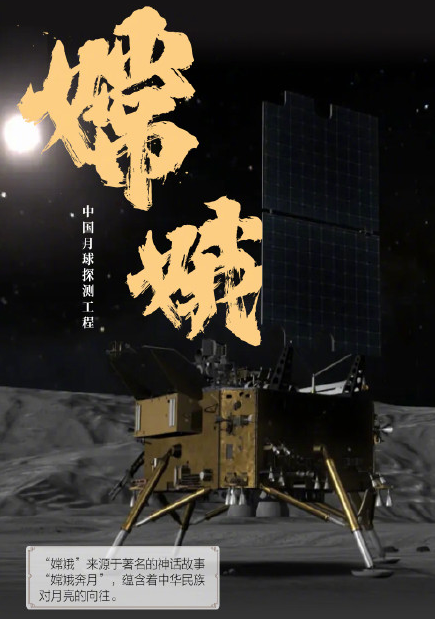

The lunar exploration program is named "Chang'e," the manned spacecraft is "Shenzhou," the global navigation satellite system is "Beidou," the solar exploration satellite is "Kuafu," the quantum computer prototype is "Jiuzhang," the planetary exploration program is "Tianwen," and the space telescope is "Mozi"... The naming of these national treasures embodies the romantic collision between modern technology and historical civilization.

Of course, Huawei was an early adopter of this approach with names like Hongmeng, Kunpeng, Ascend, and Qinkun. In this generation of names, people's names often come from the Book of Songs, and corporate names somehow have to be related to Shanhaijing.

Some say that Chinese companies have begun to find their own cultural matrix and parasitize it to form their own brand symbols.

In fact, China's cultural matrix is not limited to Shanhaijing, and brand culture should also be reflected in every touch point with consumers. Simply choosing a name is more like a far-fetched analogy.

Note: Some images are sourced from the internet. If there is any infringement, please contact us for removal.