Commercial Space IPOs Take Off Collectively: Is Capital Betting on the Next 'Chinese SpaceX'?

![]() 01/16 2026

01/16 2026

![]() 392

392

Over the past decade, China's commercial space sector has always teetered on the 'fringe of national projects' while occupying the 'heart of capital's imagination.' Unlike the new energy sector, which boasts a clear industrial rhythm, or semiconductors, with a well-defined path for domestic substitution, and lacking the ability to swiftly close commercial deals like the internet industry, commercial space has long been a unique blend of ambition and uncertainty.

However, the landscape is now shifting. With the formal rollout of detailed IPO regulations tailored for the commercial space sector, private rocket firms, once confined to the realms of financing rounds and project roadshows, are now poised to collectively make their debut on the capital market.

Image source: Pixabay Library

Currently, a slew of enterprises, including LandSpace, Galactic Energy, CAS Space, Space Pioneer, and i-Space, have either completed or initiated listing guidance with local securities regulatory authorities. Meanwhile, companies like BDStar Navigation and Fuxin Futong have opted for a dual-track strategy, aiming for a listing on both the A-share and Hong Kong stock markets.

Driven by the convergence of policy, market, and capital forces, the commercial space sector appears to have entered a true 'golden window period.' Yet, the question looms: Is this the dawn of a sustained industry takeoff, or merely a premature realization of capital's lofty expectations?

The IPO Fast Lane Begins: Who Will Be China's SpaceX?

In the past, China's commercial space sector was predominantly in the 'PPT rocket' phase, characterized by diverse technical routes, vague business models, and a reliance on financing for survival rather than order-driven growth. Rockets were seen as stories, launches as milestones, but the sustainability of the business model was seldom questioned.

Today, the capital market's perspective has evolved.

With multiple private rocket companies entering the listing guidance phase, the market's focus has shifted from technological breakthroughs to engineering prowess and cash flow predictability. What truly matters now is not a single successful launch but the ability to consistently demonstrate launch frequency, success rates, single-launch costs, and order visibility in prospectuses.

Take Galactic Energy, for instance; its 'Ceres' series of solid rockets has established a relatively stable launch cadence and is continuously expanding downstream application scenarios in commercial remote sensing and low-Earth orbit constellation missions.

LandSpace, on the other hand, is betting big on a reusable route for its liquid oxygen-methane engines and medium-to-large launch vehicles, aiming to mirror SpaceX's early technological trajectory.

CAS Space, backed by the Chinese Academy of Sciences system, enjoys stronger institutional synergy and engineering capabilities. Space Pioneer has carved its niche with medium-to-large liquid launch vehicles, emphasizing rapid iteration and engineering efficiency.

Despite their diverse paths, these companies share a common thread: they are no longer just selling 'space dreams' but are beginning to prove three critical aspects to capital. First, whether their technology forms a closed loop rather than remaining confined to laboratory achievements. Second, whether orders are sustainable rather than one-off projects. Third, whether their business model can withstand economic cycles rather than relying on policy windows.

More critically, the demand side is undergoing a transformation. Previously, rockets were the supply-side protagonists, but now, the construction pace of low-Earth orbit satellite communications, remote sensing, and navigation constellations is dictating rocket capacity planning.

Satellites are no longer one-time endeavors but infrastructure requiring continuous network supplementation, maintenance, and upgrades, implying the emergence of stable, high-frequency, and predictable launch demands.

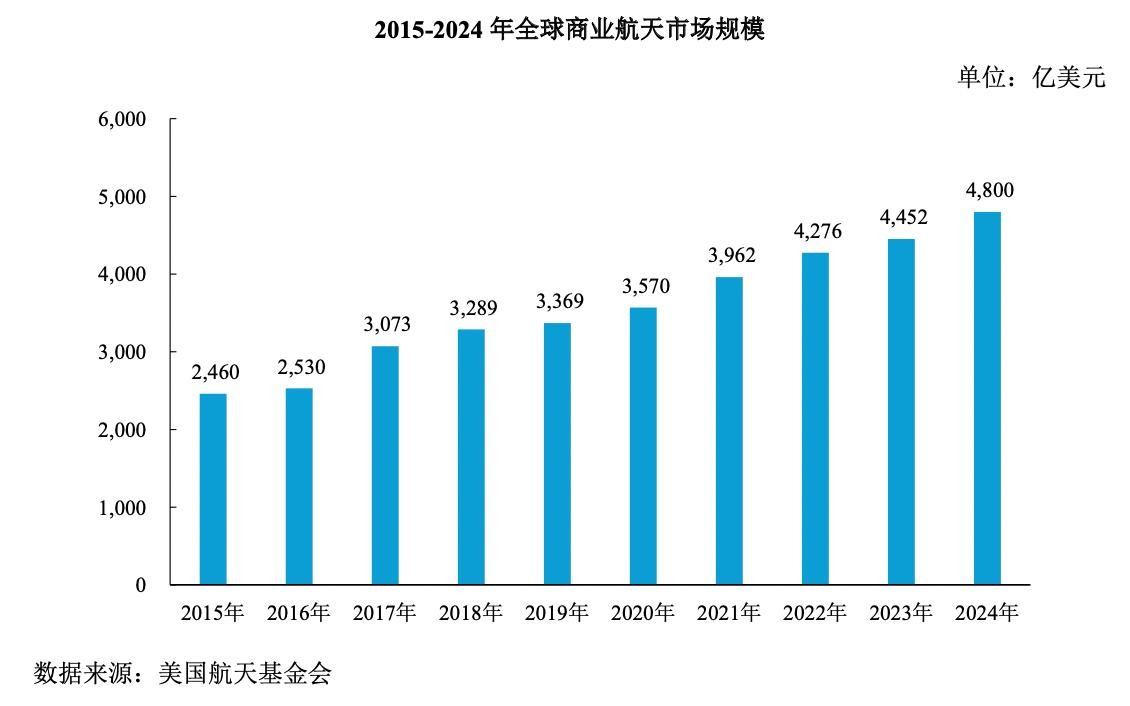

According to the U.S. Space Foundation's 2025 'Space Report,' the global space economy reached $612 billion in 2024, with commercial space revenue accounting for $480 billion, or 78%.

The transition from 'PPT rockets' to the IPO fast lane is not a sudden surge in capital boldness but a reflection of the commercial space sector presenting, for the first time, an auditable, replicable, and predictable business logic.

At this juncture, capital is truly betting on who can become an indispensable 'infrastructure provider' in the low-Earth orbit constellation era through a high-frequency, low-cost, and replicable launch system.

SpaceX vs. the Chinese Model: Private Efficiency vs. National Systems Engineering

As commercial space enters the infrastructure stage, how should efficiency be defined? Globally, SpaceX seems to offer a benchmark.

From technological radicalism to extreme engineering efficiency, SpaceX has reshaped the U.S. aerospace industry's organizational approach with a single company's capabilities. It compresses costs through reusable rockets, streamlines the industrial chain through highly vertically integrated systems, and continuously bets on high-risk, high-investment long-term goals with capital patience.

However, the downside of this model is the U.S. aerospace system's high dependence on a single private company. While SpaceX enhances efficiency, it has, in fact, 'hijacked' the national aerospace rhythm. Whether for manned spaceflight, military launches, or low-Earth orbit constellations, key nodes of U.S. aerospace are increasingly concentrated in one enterprise.

China, in contrast, has chosen a vastly different path.

Image source: Pixabay Library

Domestically, the national team shoulders the responsibility for breakthroughs in underlying technologies and safety boundaries, while private commercial space focuses more on cost, frequency, and application-layer markets. In essence, China is not attempting to replicate a 'Chinese version of SpaceX' but is constructing a multi-entity systems engineering model.

Under this structure, the national aerospace system ensures 'certainty,' private enterprises drive 'efficiency spillover,' and the capital market facilitates risk dispersion and expansion acceleration. Commercial space companies can fail, but the system cannot; enterprises can be aggressive, but the system must remain stable.

This explains why, while China's commercial space sector may not reach the same efficiency ceiling as SpaceX, its systemic risk is significantly lower. It does not bet on the success of a single company but increases the success probability of the entire system through parallel exploration by multiple companies.

This is also the fundamental reason why companies like BDStar Navigation and Fuxin Futong, focusing on spatial positioning and satellite communications, are included in the same 'commercial space narrative.' Navigation, communications, and rockets are no longer isolated assets but crucial components of an integrated system.

Overall, the two models are not simply opposed but are inevitable outcomes of institutional, capital structure, and industrial division of labor differences. What truly merits discussion next is not who resembles SpaceX more but how the Chinese model can forge a sustainable commercial space path between 'private efficiency' and 'national-level systems engineering.'

The Future of Commercial Space is Taking Shape in China

What will truly determine the direction of the space industry in the future will not be the success of a single launch but rather changes in demand structure.

In the past, space demand was typically exploratory: low-frequency, non-replicable, and centered on national missions. Today, however, low-Earth orbit satellite communications, remote sensing, and navigation are gradually evolving into global digital economy infrastructure, with logic closer to that of communication towers and cloud computing data centers than research projects.

Image source: Pixabay Library

Once entering the infrastructure stage, the core variables of industrial competition undergo fundamental changes. Valuation no longer revolves around technological breakthroughs but is priced using more traditional industrial and utility logic: launch frequency multiplied by single-launch costs, order visibility corresponding to cash flow stability, and system redundancy and national security attributes constituting additional valuation premiums.

Under this logic, distinctions emerge between platform-type assets and cyclical manufacturing. Companies with launch service platform attributes and deep ties to low-Earth orbit constellation construction are more likely to secure long-term cash flow and valuation premiums. In contrast, manufacturing companies relying solely on a single rocket model and lacking sustained orders are closer to cyclical assets.

China's unique advantages at this stage include, first, supply chain completeness. China is currently the only country globally capable of achieving highly localized and scaled manufacturing across materials, engines, electronics, and satellite integration. This means that when demand truly surges, Chinese enterprises have the foundational conditions to transition rockets from engineering products to industrial products.

Second is demand certainty. National security, digital infrastructure, and remote sensing applications form a long-term and stable demand base. This demand does not pursue extreme efficiency but highly values reliability and controllability.

This is also why many space application companies choose to make a push for IPOs at this stage. Their core assets are not single-point technologies but long-term cash flow expectations embedded within the national system.

Therefore, the current opportunity in China's commercial space sector lies not in a single 'space unicorn' but in a complete track transitioning from national projects to industrial infrastructure. Meanwhile, the U.S. commercial space sector is at a critical juncture of high concentration, valuation overextension, and systemic single-point failure.

If the concentrated launch of this round of commercial space IPOs marks the beginning of an era, what it truly declares is that China's commercial space sector is being placed within a larger coordinate system for the first time. It is no longer just a collection of technological breakthroughs or capital stories of single-point companies but a set of national-level industrial infrastructure taking shape.

Source: Songguo Finance