Feishu goes up, DingTalk goes down

![]() 11/01 2024

11/01 2024

![]() 650

650

Written by | Wu Kunyan

Edited by | Wu Xianzhi

The slow development of China's to B software is largely due to the fact that Chinese enterprises are heavily concentrated at the top and tail, with few in the middle.

Wang Huiwen's judgment on the enterprise service market years ago is like a curse, requiring most enterprise service enterprises to either float upwards or sink downwards to target sufficient customer groups and markets, thereby developing products with purpose.

Just looking at the big three in collaborative office software, besides WeChat Work, which is backed by WeChat's private domain moat, DingTalk and Feishu have differentiated in similar paths.

The similarity is that both are on the path of persevering with AI, using low-code as an important underlying implementation vehicle. DingTalk has been preaching low-code for years, which is inherently part of DingTalk's open ecosystem design. In contrast, Feishu's star product, Multi-dimensional Tables, is inherently a form of low-code implementation, and the Multi-dimensional Table Database and Low-code Platform unveiled at this year's Feishu Conference can be seen as further implementation practices of AI + low-code.

The difference is that DingTalk, which has always adhered to an open ecosystem, sells its abilities, either actively or passively "choosing" to sink downwards, leaving competitors far behind on the road to inclusivity. On the other hand, Feishu, which has never given up on its all-in-one approach, inevitably floats upwards, attempting to increase customer value through ultimate tool efficiency.

This can be glimpsed from their different pricing models: DingTalk charges by organization, while Feishu charges per user. Taking basic paid services as an example, a 200-person organization serves as a watershed.

The increasingly clear path divergence points to the respective "comfort zones" of DingTalk and Feishu.

PaaS giving way to aPaaS?

Large companies all have to B genes. Jack Ma's statement, "Let there be no difficult business in the world," gave birth to Taobao, arguably the most successful "PaaS ecosystem," which to some extent also propelled DingTalk to become the most widely used collaborative office product today.

The massive number of users belong to different groups, corresponding to extremely complex implementation scenarios, which means it is basically impossible to create a general-purpose product that satisfies everyone. On the other hand, as the leader in collaborative office software, DingTalk is a pioneer in educating the entire market. In the eyes of investors, it also carries the upper limit of imagination for this market.

"If Chinese enterprises are more willing to pay for office software, a change that will inevitably occur is that DingTalk will become more profitable." Following this logic, scale becomes the main storyline in the DingTalk narrative, from which its base positioning and open ecosystem are derived. Rather than becoming heavier and heavier on its own, it is better to open up the ecosystem and let partners grow together.

DingTalk's low-code is also a product of this logic: Since it is impossible to meet the refined needs of enterprise organizations, a general low-code platform is created. Whatever business needs and logic are required, "let them handle it themselves."

In this "script," DingTalk only needs to continuously expand its ecosystem to serve as a traffic entry point, waiting patiently for domestic enterprises' willingness to pay to increase. However, in this process, DingTalk and its partners gradually transitioned from cooperation to "co-opetition."

On the DingTalk foundation, the low-code platform (aPaaS) "Yida" is the second layer, while "Cool Apps" (PaaS ecosystem applications) are the third layer. When the development threshold for Yida is low enough, and internally built applications by enterprises sufficiently meet basic digitalization needs, it may squeeze the ecosystem of the application market.

Typically, partners within DingTalk's PaaS ecosystem, such as Polaris and eSign, release entry-level standard products on the DingTalk application distribution platform. Most of these applications have an annual fee of around 10,000 yuan. Even if they are only targeted at categories like OKR and CRM suites or specific vertical tracks, their level of refinement is still limited and can even be considered "trial versions" to attract business owners to pay for projects.

Internally built applications through Yida by enterprises can serve as "alternatives." Since the self-building process is similar to customization, low-code applications may even be more suitable for the enterprise itself. With the AI-ization of low-code, whether it's smoother output of AI capabilities from the development side or functions targeting inexperienced developers through AI recognition logic, both further expand the reach of low-code.

On the other hand, low-code itself is just an "additional product" for purchasing DingTalk's exclusive version, with an annual fee of 9,800 yuan being almost the only software expense for enterprises.

From an ROI perspective, using Yida to build self-applications is relatively more "cost-effective."

Unrestricted use of low-code and the accompanying capabilities such as data storage and circulation are important levers for DingTalk to leverage the massive number of small and medium-sized enterprises eager for digital transformation. But this also raises a new question: How should the relationship between low-code and the ecosystem be handled?

Currently, DingTalk's solution is to jointly develop out-of-the-box atomic suites with ecosystem partners, increasing revenue channels and exposure opportunities for them.

A typical example is the DingTalk Collaboration Suite. As an out-of-the-box tool for the ecosystem foundation itself, according to official news released at the ecosystem conference in June this year, cooperation revenue from ecosystem partners including Polaris, eSign, and Moka in the DingTalk Suite has approached 100 million yuan.

On the other hand, DingTalk is also continuously consolidating openness on the basis of its ecosystem. Taking the e-commerce industry as an example, leading domestic e-commerce platforms have all opened data interfaces to DingTalk, which can serve as a platform for data aggregation and processing. Enterprise service tools from different e-commerce ecosystems can also find monetization opportunities within this.

PaaS and open ecosystems are not easy, as the channel weight of ecosystem partners will continuously change with the platform's commercialization pace. As the common denominator grows larger, DingTalk also needs to consider how to maintain this delicate balance.

Recognize the reality

The theory of large companies' to B genes also applies to Feishu, but due to the particularity of its market segment, while inheriting some of ByteDance's genes, Feishu is also vigorously resisting certain aspects of them.

ByteDance's core is efficiency. From Toutiao and Neihan Duanzi to Douyin, Xigua Video, and Tomato Novel, they are essentially variants of the information stream. This "eye-catching" business all follows a similar business model—improving customer acquisition and retention (duration and frequency) efficiency is sufficient to build an information entry effect to a certain extent and gain distribution rights.

At this point, all ByteDance needs to do for commercialization is to maximize monetization efficiency within a unit of time. Whether it's the pre-link of commercialization or the commercialization itself, ultimate efficiency is its ultimate goal. This extends to Feishu, specifically manifested in products we see such as Multi-dimensional Tables, People, and Dashboards, but to B follows a completely different logic.

The inapplicability of traffic and algorithms, as well as the oft-repeated practice of using to C thinking for to B, are all things Feishu needs to resist. In addition, a bigger problem may lie in its excessive investment in products, which is inversely proportional to product monetization efficiency.

Externally, the labor costs for small and medium-sized enterprises are relatively low, and the margins are not obvious, meaning Feishu's monetization efficiency on them is not high. To match the intensity of developing and maintaining Feishu's all-in-one products, increasing customer value became the only "tightrope" Feishu had to walk in the end.

Ask yourself, based on Feishu's latestly released products, what size of enterprise can utilize Multi-dimensional Tables with a single table capacity exceeding 1 million rows or Dashboards that can count 10 million rows of data?

Furthermore, within Feishu's product matrix, atomic suite tools are the core of its output efficiency. Under the reconstruction of AI, the aforementioned impressive product performance also integrates the capabilities of star startups such as Dark Side of the Moon and Zhipu AI. For example, the "Field Shortcut" function of the new Multi-dimensional Tables operates structured data in tables in bulk by encapsulating AI.

When the integrated tools have reached a certain level of integration, other internal applications become increasingly redundant—customers need to conduct business following Feishu's logic, and the low-code platform is merely a tool opened to a few customers for "patching." In contrast, DingTalk views low-code as a grip and foundation, leaving greater permissions in the hands of customers, with AI being relatively more oriented towards a "supporting" role.

As such, small and medium-sized enterprises with low monetization efficiency are "naturally" abandoned by Feishu. We understand that a sales organization of about 200 people in the southeast region spends 200,000 yuan annually on Feishu. Another SaaS enterprise with a thousand employees has an annual Feishu fee of up to 2 million yuan, accounting for one-fifth of the company's cash flow.

Defining it using an imported concept, Feishu's growth logic was forced to evolve from a relatively pure PLG (product-led growth) to PLG + SLG (sales-led growth). However, just as the aforementioned genetic conflict, Feishu cannot afford a complex sales organization internally and has also failed to build a mature tiered agency system.

An integrator who has had contact with Feishu told Photon Planet that Feishu's agency system was once unclear and there were even cases of internal direct sales and agents "competing for food": "Basically, for customers contacted by direct sales, it's difficult for us to get rebates."

Additionally, Feishu has requirements for integrators' organizations. Except for a few first-tier cities, it is difficult for integrators to meet the pre-sales organization size required by Feishu.

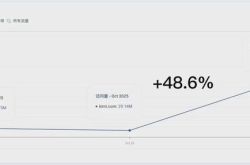

Fortunately, as a "tool" for ByteDance to implement its own concepts, Feishu's growth is also supported by ByteDance's endorsement. A source close to Feishu said that due to its positioning, Feishu is more determined to acquire key accounts (KA) compared to the other two competitors. On the other hand, ByteDance's rapid growth has also created a certain fear of missing out (FOMO) mentality among KA customer groups. This allowed Feishu to acquire a considerable number of KAs from 2020 to 2022, and its revenue scale once became the largest among the three.

"With high customer value, customers are unlikely to migrate easily, and they can accept a slight price increase, which ensures stable revenue."

After clarifying its positioning and strategically abandoning small and medium-sized organizations, Feishu resolutely initiated layoffs, and breaking even seems to be within sight. Feishu, which has been rushing ahead under the KA strategy, is guarding a large but small head, seemingly further away from the middle and tail.

Find a new story

Floating upwards and sinking downwards are not only strategies but also necessities for DingTalk and Feishu to seek growth in the enterprise service market. However, this does not mean they completely abandon growth opportunities outside their areas of strength.

Just as we see increasingly bloated Super Apps today, once a product reaches scale, it cannot converge on its own. Therefore, we can see Feishu actively opening up its ecosystem, while DingTalk continues to launch atomic suites.

However, the significance of these actions lies more in "coverage." As AI subtly changes all aspects of our lives, individuals empowered by AI become new opportunities for collaborative giants in wealth distribution.

As we all know, long before the AI wave, Wolai, the predecessor of DingTalk Docs, and Feishu Docs were already favorites of many content producers and digital nomads. This sufficiently proves that in the mobile internet era, individuals and organizations share a similar pursuit of efficiency.

With the expansion of collaborative giants based on OA, these efficiency applications that were originally "owned" by individuals have also been gobbled up by the market. This does not mean that individuals' demand for efficiency has disappeared; rather, individuals have felt and accepted the productivity revolution brought about by AI before enterprises.

The 2024 Work Trend Index Annual Report released by Microsoft and LinkedIn previously pointed out that 78% of AI-proficient employees have used AI without their employers' permission or knowledge. Individuals' agility determines that they will inevitably embrace technological revolutions before organizations, and even in the usage of massive individuals, the boundaries of products can be more effectively expanded.

Scholar Wu Chen also mentioned in a small-scale sharing that the AI era may not necessarily give birth to super giants but will certainly give birth to super individuals. Just as the open-source community drives the development of AI, individuals are also more agile feedback system builders compared to enterprises.

Even in terms of business models, we can find pioneers with similar paths. According to Kingsoft Office's 2023 annual report, its 2023 revenue was 4.5 billion yuan, with subscription revenue of 3.6 billion yuan and a net profit of 1.3 billion yuan.

Doing business with individuals, or to P (professional) business, Feishu's products inherently have certain advantages. However, from a layout perspective, DingTalk is the pioneer among the two. It is reported that DingTalk's newly launched DingTalk 365 Membership is a subscription-based paid product targeting this market, integrating more personalized settings including AI assistants, AI search, and automated replies.

Moreover, new changes in collaborative office software are likely to occur in this round of redistribution during the overseas expansion and the turnover of old and new domestic enterprises. A few months ago, DingTalk's overseas expansion and its competition with Feishu for customers in emerging markets such as embodied intelligence and AI startups were tug-of-wars beyond products.

As the strategies and paths of DingTalk and Feishu become increasingly clear, the stalemate may begin to be broken. This has given "development time" to AI, which is more likely to break the stalemate.