Automobiles Going Overseas: A New Era of Farming

![]() 08/14 2025

08/14 2025

![]() 629

629

The question of globalization looms large for Chinese automakers.

"Upon leaving Bangkok's airport, every giant billboard boasts Chinese cars."

Jin Jun, the lead partner of PwC China's automotive industry, shared this observation at a recent forum. He had just returned from a trip to Thailand.

Starting from Bangkok's Suvarnabhumi Airport, SAIC MG, BYD, and GAC Aion posters line the highways. These brands are not just a presence on Thai streets; they are also visible throughout European cities, with MG, NIO, and XPeng making their mark.

In 2024, China's total vehicle exports reached 6.41 million, a 23% year-on-year increase. New energy vehicle exports performed even more impressively, with China accounting for 70% of the global market share. Chinese automakers exported over 1 million vehicles within a year for the first time. All data and observations point to one conclusion: "The speed of Chinese cars going overseas is accelerating."

Major automakers are vigorously expanding their overseas territories. Changan Automobile's Rayong factory in Thailand has commenced production, SAIC Motor has unveiled its overseas 3.0 strategy, and Chery Group has been the champion in passenger vehicle exports among Chinese brands for 22 consecutive years.

It's undeniable that Chinese automakers are transitioning from "product exports" to "industrial exports" when venturing overseas. However, amidst the rapid industry changes, as they strive to become world-class automotive brands, they face both glory and challenges.

Two Contradictions

What is the biggest contradiction for thriving Chinese automakers in both domestic and international markets?

"Why can't the Chinese automotive force that dominates the domestic market replicate that same success in overseas markets?" is undoubtedly one of them.

In the domestic market, Chinese automakers have finally achieved "their hometown, their main stage," eroding the market share of multinational giants to almost nothing. Data from the first half of this year shows that the market share of joint venture brands has declined to 36%, less than 40%.

As everyone knows, these achievements stem from the electric vehicle era. Relying on technological iteration, cost advantages, and a deep understanding of the market, they have launched a devastating offensive against joint venture brands in the domestic market. The new wave of Chinese automakers going overseas is also driven by new energy vehicles.

When automakers bring the determination to overturn the global fuel vehicle era and the strength to dominate the Chinese market, preparing to make a significant impact on the path to globalization, they discover that this journey is even more rugged than anticipated.

First and foremost, the path of Chinese automakers going overseas faces a high wall erected by trade protectionism.

Trump's tariff stick "can be waved however he wants," Europe's strict regulatory requirements and protectionist policies, financial interest rate fluctuations in Southeast Asia, and even the "backstabbing" incident in the originally "buddy-buddy" Russian market all reflect two points: the threat posed by Chinese automotive power and the deep dilemma faced by Chinese automakers going overseas.

Beyond the high wall of protectionism, Chinese automakers also grapple with another contradiction: the challenge between "rapid expansion" and "slow pace."

As the art of war teaches, speed is crucial. To seize the first opportunity, the pace of going overseas must be swift, especially for those who didn't start early and can only win with speed.

Previously, XPeng Motors integrated into the community in Northern Europe by sponsoring local handball leagues, demonstrating Chinese brands' efforts to integrate into foreign cultures. The goal was to use competitive cultures to introduce Chinese culture to the local area and let Northern Europeans "know XPeng and understand XPeng."

From the perspective of a new brand "seeking attention," XPeng's offensive pace is "fast." However, from the perspective of cultural infiltration, a few games cannot eliminate the time required for cultural precipitation and cannot achieve a "quick win." The integration of foreign cultures is a "slow pace."

Of course, the conflict between fast and slow is not unique to XPeng but is a challenge faced by almost every Chinese automaker going overseas.

This challenge also creates a certain contradiction with the consumer habits of foreign markets. Chinese automakers progress rapidly in the car sales process but still lag behind in financial services, insurance support, and other aspects, restricting the enhancement of brand value.

Even in terms of work mode, "China's way of doing things doesn't work in foreign countries." In pursuit of efficiency and speed, the Chinese market has long been accustomed to the 996 model, but this model doesn't work in places like Europe and Southeast Asia. For example, there are strict working hour restrictions in Europe, and "working overtime alone can even make local European colleagues feel uncomfortable."

From the invasion of Chinese automotive culture to the running-in of car buying habits to the mutual adaptation of domestic and foreign team work modes, they are all filled with the contradiction of "fast and slow." It's time to rethink the "art of speed and patience."

Cost, Still Cost

The speed of expansion means significant "capital investment."

As the chairman of Baolong Technology, a manufacturer of intelligent and lightweight automotive products, Zhang Zuqiu calculated a simple account for automakers going overseas. "The cost of overseas manufacturing is generally 30%-60% higher than that in China."

Although various tariff thresholds are forcing Chinese automakers to build factories in local markets, compared to building factories, most Chinese automakers choose a compromise solution of "research and development in China, service overseas." Even so, cost remains a sword of Damocles.

Making foreign consumers aware of the brand is the first step in selling cars, and advertising becomes a necessary means.

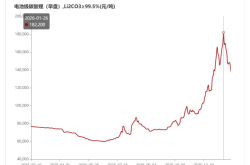

Much like the airport road in Chengdu, the huge and eye-catching billboards on the Thai airport road have become a must-fight spot for automotive brands. It is reported that in the lively competition, the price of advertising billboards has risen from around 30,000-40,000 RMB to about 60,000 RMB, with a minimum lease period of two years.

The rising cost of billboards is just a "drop in the bucket," and the transportation cost of exporting overseas has also made many automakers "scratch their heads."

The daily rental fee for a ro-ro ship specifically used for transporting automobiles reaches $150,000. Shipping from China to Europe takes about 40-60 days by sea, with a total cost of $9 million. Calculated based on 6,500 standard parking spaces on a ro-ro ship, the transportation cost per vehicle is nearly $1,400, equivalent to nearly 10,000 RMB.

What does this single-vehicle transportation cost mean? The proportion of Japanese automotive transport ships is 15 times that of China's. Taking Chery, which has performed well in overseas exports, as an example, data from the first three quarters of 2024 shows that the average net profit per vehicle is about 7,345 RMB/vehicle. Although this is a significant increase compared to 2022 and 2023, it still cannot cover the cost of transporting a single vehicle to overseas markets.

Therefore, capable automakers buy their own ships for transportation. In 2024, BYD's ro-ro ship "Pioneer 1" was put into operation, SAIC Motor invested billions to build 14 ships, and Chery Automobile ordered 3 ro-ro ships with 7,000 parking spaces.

Those automakers that cannot afford to buy ro-ro ships can only pay high transportation costs. Moreover, these costs are all incurred "before selling cars."

Selling cars means "adapting to local conditions." Only cars that meet local usage habits and regulations can be sold. Just like foreign brands entering the Chinese market, they are all committed to "localization," "Chinese design," "research and development for Chinese market demand," etc.

Equivalent requirements, such as chassis tuning, crash tests, emission standards, etc., all need to be considered clearly by Chinese automakers in the early stages of product development. It will be very difficult and costly to make changes later.

For example, the AEB function can still be sold without it in the Southeast Asian market. "In Southeast Asian countries, the premium of Chinese automotive brands is not particularly high. They emphasize cost-effectiveness and cost advantages," an industry insider said.

However, in the European market, without AEB, trying to sell cars is like "courting disaster." In the era of intelligence, the Intelligent Speed Assistance (ISA) system is not yet mandatory in China, but the European Union requires all new cars to have ISA from July 7, 2024.

In addition, the advanced driver assistance systems that Chinese automakers are proud of also face some incompatibility in Europe. When evaluating XPeng models in Europe, it was felt that the lane departure warning function in XPILOT was too aggressive.

The foreign media InsideEVs wrote in its report, "XPeng seems to still be trying to figure out what Western buyers really want so that they can adjust their vehicles to meet different needs."

"The technical threshold in the European market is high, and the cost of technical upgrades and product modifications alone requires at least tens of millions of yuan," said an automaker that has been going overseas for many years. Even if the demand is met, the first step to selling cars abroad is to obtain certification.

Certification involves dozens of tests. Due to the large differences in road environments, automakers also need to conduct local adaptability tests, data tests, and collection, which is another considerable expenditure. If necessary, it is also necessary to conduct the authoritative European E-NCAP test, which costs approximately 5-8 million yuan per round.

The car hasn't even started selling, and the money has already been painfully spent.

Struggling with Rules

After everything is done, cars may not be that easy to sell.

Who knows, if you can gain a foothold in Europe, it will represent a new stage for Chinese automakers going overseas. But everyone also knows that this is difficult.

The Port of Antwerp-Bruges in Belgium, the largest automotive port in Europe, has been leased by some Chinese automakers for large areas to use as parking lots. Some electric vehicles have even been parked at the port for 18 months.

"Currently, the number of vehicles at the Port of Antwerp significantly exceeds the levels in 2020 and 2021," said a port spokesperson. Major European ports such as the Port of Bremen in Germany and the Port of Rotterdam in the Netherlands are also filled with Chinese electric vehicles, "densely packed."

Data shows that in the first half of the year, the combined market share of Chinese brands in the electric vehicle market of 14 European countries reached 8%, but behind this, it almost relies on the sales support of BYD and SAIC MG.

Although BYD and MG are taking the lead, the difficulty lies in the fact that the European automotive industry is facing a life-or-death decision in the transition to electrification. The traditional production system for internal combustion engine vehicles in the century-old automotive industry has become extremely mature, making the transition to electrification slow and the market demand for electrification cooling.

The "life-or-death decision" of the European market imposes two constraints on Chinese automakers going overseas.

One is the potential for high fines. Due to excessive carbon emissions and the inability to meet the EU's 2025 emission targets, they may face fines of up to 15 billion euros. According to the European General Data Protection Regulation, only necessary data such as location is allowed to be collected, and it can only be stored within the EU, with strict conditions for cross-border transmission, which may also face high fines.

The other is that the increase in global trade barriers and the adjustment of tariff policies have made the globalization of the supply chain more complex. Some countries not only require supply chain companies to build factories locally but also require the localization of second- or even third-tier suppliers.

Previously, a power battery company purchased land locally and mandatorily called on some suppliers to join and set up factories only to discover that the local power grid could not support the cluster production demand.

This incident reflects a more complex trust and implementation challenge faced by supply chains going overseas. Liu Mingyang, general manager of Jiwen Metal Technology, shared a situation where they introduced newly built local production capacity to a global OEM customer, and the other party asked a question, "Is this specifically prepared for our project?"

The answer was only no.

"If the answer is yes, the other party will directly question the intention of 'tailor-made capacity' and the anti-risk ability of the supply chain."

In the 2.0 era of Chinese automakers' global expansion, the challenge lies in how to "penetrate" and achieve deep integration, a "new narrative" that tests a myriad of abilities including technology, capital, management, strategy, and cultural adaptability.

Toyota's global market profits surpassing the combined sales of 30 million new cars in China underscores the fact that global market dominance doesn't hinge on a single area of expertise. An industry expert remarked, "Chinese automakers venturing overseas must adopt a 'farmer's mindset'."

The cornerstone of this 'farmer's mindset' is identifying the right "soil" and rhythm for oneself.

With limited resources, the key is to operate with light assets. By partnering with local enterprises and integrating into the customer supply chain, the risk associated with heavy asset investments can be significantly mitigated. For instance, Zero Run and Stellantis jointly established "Zero Run International" to leverage the local channel network, enabling entry into the European market with minimal capital expenditure.

The next step involves continuously "cultivating" and implementing a phased localization strategy. As an industry insider explained, "Tailor your operating strategies to the unique cultures and demands of each market." The 2.0 phase of going overseas necessitates a holistic evaluation of local cultural compatibility, resource supply stability, and one's own capability boundaries, evolving from mere "product exports" to "technology + ecosystem + brand" exports.

Patience and perseverance are vital. Globalization is a marathon, not a sprint, and success doesn't come overnight. An industry expert noted, "Over the years, Chinese auto exports have encountered numerous obstacles. For Chinese automakers to truly become locally embedded enterprises overseas is indeed a formidable challenge."

Building brand trust through long-term vision and deeply localized global operational capabilities are critical areas where Chinese automakers need to catch up.

While striving to close the gap, it's equally important to avoid replicating the fierce domestic competition overseas. Overseas, Chinese automakers form a community with a shared future. While competing, they must also support each other.

Yin Tongyue, Chairman of Chery Automobile, emphasized, "We all wear the same hat: 'Chinese Auto'. Our fates are intertwined. We cannot extend price wars overseas nor engage in slander or undermining each other, as it only invites ridicule from others."

Note: Some images are sourced from the internet. If there is any infringement, please contact us for removal.

-END-