Fantastic! Achieving 0 to 100 km/h in no less than 5 seconds. Not all power can work wonders.

![]() 11/13 2025

11/13 2025

![]() 547

547

I wholeheartedly concur.

Author|Wang Lei

Editor|Qin Zhangyong

In an era where horsepower abounds, the government is finally reining in high-speed vehicles.

Recently, the Ministry of Public Security has put forth a draft mandatory national standard for public comment, titled 'Technical Conditions for the Safe Operation of Motor Vehicles.' This draft proposes a series of specific requirements to ensure the safe operation of motor vehicles.

Clear limitations have been imposed on vehicle performance, stipulating that passenger vehicles should, by default, have an acceleration time from 0 to 100 km/h of no less than 5 seconds after each start.

In simpler terms, whether you purchase a high-performance gasoline car or an electric vehicle in the future, the default acceleration time from 0 to 100 km/h will have to exceed 5 seconds.

Given the high bar for acquiring high-performance gasoline cars with acceleration times under 5 seconds, it's evident which types of vehicles this new mandatory national standard primarily aims to regulate.

Following the release of the new national standard draft, the public's response to the acceleration performance restrictions has been quite vocal. Many have lauded the move, viewing it as a necessary course correction for the unchecked growth of new energy vehicles.

'Finally, those exaggerated promotional claims will be regulated.'

The language has been tightened to prevent an excessive pursuit of speed. With new energy vehicles typically starting at 4 seconds, the market competition standards are also poised for a shakeup.

01

Striking a Balance Between Safety and Performance

While restrictions are in place, they are not a one-size-fits-all solution.

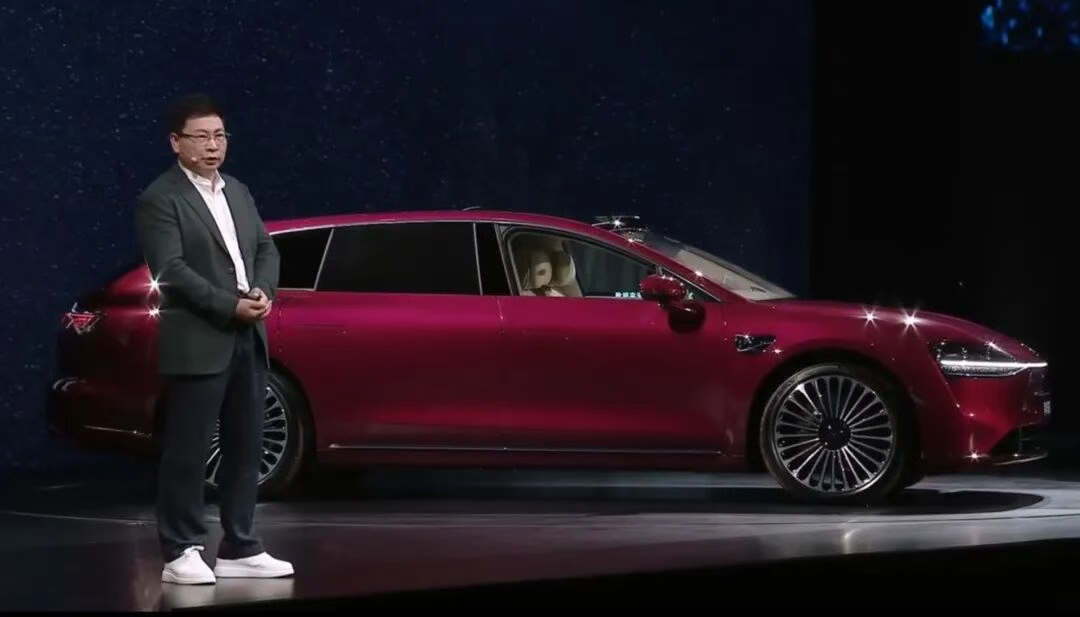

Let's delve into the specific regulations. Passenger vehicles should, after each power-on or ignition (excluding automatic engine start-stop), default to an operating state where the acceleration time from 0 to 100 km/h is no less than 5 seconds.

The new regulation refers to the 'default operating state.' This means vehicles are not barred from offering higher performance in non-default modes.

It merely mandates restrictions in the default mode, implying that acceleration limits can be lifted through driving mode switches after the user actively selects them. It's not a direct cap on performance but rather aims to ensure drivers are consciously taking certain actions when utilizing high-acceleration modes to enhance their driving preparedness.

As a result, electric cars capable of easily surpassing the 3-second acceleration barrier will start more gently after each restart, indirectly boosting safety.

Upon the release of the new regulation, netizens expressed a range of opinions. Some argued that human factors were at play, and 5 seconds could still lead to reckless driving. 'Is it the car's fault? It's the driver's.'

Regarding the rationale behind this revision, officials provided supplementary explanations:

In recent years, there have been multiple incidents of uncontrolled acceleration during the startup of pure electric and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, primarily due to the driver's inadequate preparation and control ability when using high-acceleration modes. Hence, it is required that vehicles start in a default operating state with lower acceleration performance to ensure drivers are consciously taking certain actions when using high-acceleration modes, thereby improving their driving preparedness. According to statistics, the acceleration time from 0 to 100 km/h for driving school trainer vehicles and most gasoline-powered passenger vehicles generally exceeds 5 seconds. Both novice and experienced drivers are more accustomed to this acceleration and are less prone to making mistakes.

The supplementary explanation already sheds light on the reason—cheap horsepower also carries potential risks.

As we all know, the torque characteristic curve of electric motors differs significantly from that of internal combustion engines. They can deliver peak torque directly at zero RPM without waiting for the RPM to rise, providing an 'instant power' response that enables new energy vehicles to accelerate faster from a standstill than traditional gasoline-powered vehicles.

This has resulted in even 200,000-yuan-level family new energy vehicles achieving acceleration times of 3 or 4 seconds from 0 to 100 km/h, making the performance of million-yuan supercars accessible at a low cost and unconditionally to every family driver's license holder.

As mentioned in the supplementary explanation, ordinary people lack the preparation and control ability for high-acceleration modes, making them prone to causing road traffic accidents. There have been numerous such incidents in the past two years.

Yu Chengdong previously stated, 'Some cars blindly pursue 2-second or 3-second acceleration, far exceeding the needs of normal roads. This excess speed is meaningless; safety is paramount.'

'We're not incapable of achieving 2-second acceleration; we've already accomplished 1.9 seconds in the lab. But under the three-dimensional constraints of regulations, roads, and user capabilities, 2-second acceleration can only remain on the racetrack.'

Moreover, the new regulation does not prohibit high performance but rather seeks to balance safety and performance through 'non-default' settings.

As early as May this year, 11 automakers jointly submitted a 'Technical Explanation on Restricting the Default Maximum Driving Force of Passenger Vehicles' to the National Technical Committee of Auto Standardization. They proposed adopting 'gentle acceleration' as the default strategy, leaving 'high performance' for users to actively choose, and providing traceable logs.

Clearly, automakers have long recognized that as driving technology advances, the rapid availability of extreme acceleration performance at affordable prices for ordinary consumers can have unintended consequences.

Additionally, regarding the 'stopwatch-style' acceleration performance of new energy vehicles, another regulation states, 'Pure electric and plug-in hybrid passenger vehicles should have a function to suppress unintended acceleration due to pedal misapplication. They should be able to detect and suppress power output when stationary or creeping and provide a clear signal (e.g., sound or light) to alert the driver.' From the description, it is clearly a restriction and warning measure designed to address 'unintended acceleration' during the startup phase of electric vehicles.

02

Intelligent Driving Demands Identification

This new mandatory national standard draft also addresses various common issues in new energy vehicles in recent years.

For instance, regarding the recent controversy over locked car door handles and safe escape, the new regulation stipulates that all doors (excluding the tailgate) must have a mechanical release function. If the vehicle is equipped with electric door handles, it must also have a mechanical emergency handle with a clearly visible logo nearby.

When irreversible restraint devices (airbags) deploy or a battery thermal event occurs, the non-collision side doors should automatically unlock, and the doors should be openable from the outside without tools. Additionally, passenger vehicles should ensure that each occupant can enter and exit through at least two different doors.

To prevent vehicle thermal runaway incidents, pure electric and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles should have the function to automatically cut off the power circuit under specific conditions. When the vehicle's speed changes by 25 km/h or more within 150 milliseconds in the longitudinal or lateral direction, or when irreversible restraint devices deploy, the vehicle should automatically cut off the power circuit to prevent safety accidents such as battery fires.

Once a battery thermal runaway incident occurs, the vehicle should alert the occupants with clear audible and visual signals. Additionally, the power battery should be equipped with directional pressure relief and pressure balancing devices, with reserved pressure relief channels to ensure that battery pressure relief does not compromise the safety of the occupants in the cabin.

For pure electric buses and plug-in hybrid electric buses with a length of 6 meters or more, it is required that the exterior of the battery box should not catch fire or explode within 5 minutes after a battery alarm, providing time for passenger safe escape.

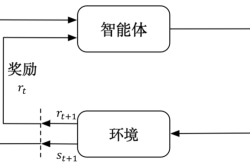

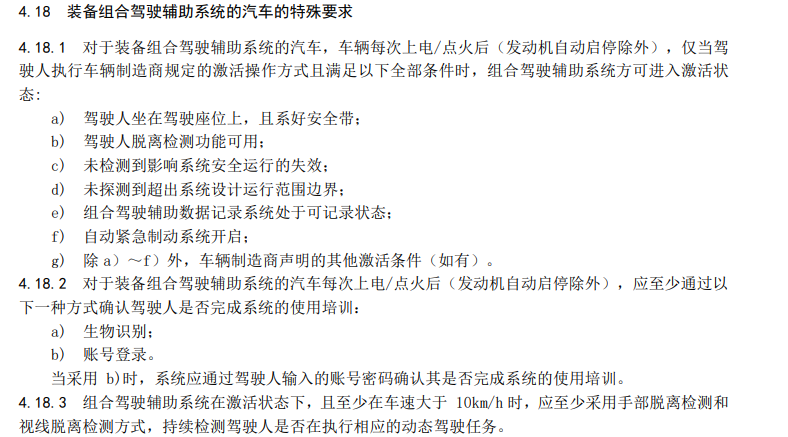

The specifications for assisted driving are still being refined. This new regulation makes verifying the driver's system usage ability a key requirement.

The new standard stipulates that after each vehicle power-on or ignition, at least one of two methods—biometric identification or account login—must be used to confirm that the driver has completed training on the use of the assisted driving system before continuing to drive.

This means that if a different person drives the same vehicle, they may not be able to use the assisted driving function unless they have also completed the system training.

Furthermore, when the combined driving assistance system is activated and the vehicle speed exceeds 10 km/h, at least hand-off detection and driver inattention detection methods should be used to continuously monitor whether the driver is performing the corresponding dynamic driving tasks.

With more and more 'entertainment screens' inside vehicles, to ensure safety while driving, the draft also requires that the display devices in the front of the driver's cabin should be turned off and prohibited from enabling entertainment image playback and gaming functions when the vehicle's speed exceeds 10 km/h. This includes in-vehicle displays and head-up display devices.

Of course, these are not all the regulations. Currently, they are only in the stage of soliciting opinions and have not been officially implemented. According to the announcement, perhaps in six months, these new regulations will replace the current GB 7258 national standard.

At that time, the specifications under the new energy vehicle system will face a new round of constraints, which will, of course, make the market safer.