Toyota and Volkswagen Executives Reshuffle: What Does FAW Still Require for Its Electrification Push?

![]() 01/04 2026

01/04 2026

![]() 518

518

Yesterday’s Champions, Unwilling to Be Tomorrow’s Obstacles

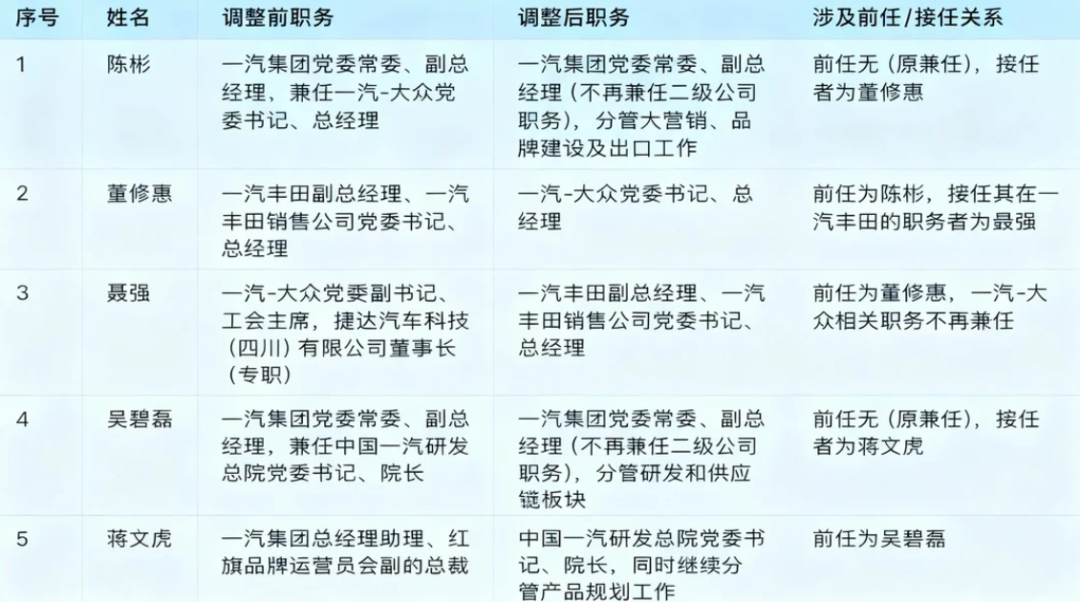

On the final working day of 2025, FAW Group unveiled a significant personnel reorganization plan for the year, triggering a wave of executive changes across its key joint venture divisions and independent brands.

The most striking features of this organizational reshuffle are undoubtedly the “return” of Chen Bin and the “reassignment” of Dong Xiuhui.

Chen Bin stepped down as General Manager of FAW-Volkswagen and moved back to the group headquarters to oversee global marketing, brand development, and international expansion. Meanwhile, Dong Xiuhui, a seasoned executive returning triumphantly from FAW Toyota, took charge of this “profit-generating joint venture powerhouse.”

Additionally, as part of this coordinated effort, Nie Qiang, the former Chairman of the FAW-Volkswagen Labor Union, quickly transitioned to FAW Toyota to fill a leadership gap. This series of interconnected moves involving six senior executives precisely covers the two most vital joint venture pillars within the group. Beyond these three, the roles of three other executives—Wu Bilei, Jiang Wenhu, and Liu Changqing—were also adjusted simultaneously.

The message from this wave of “reshuffles” is unmistakable: FAW’s “commanders” are withdrawing from frontline operational roles and returning to the central headquarters.

This strategic shift from on-the-ground execution to group-level coordination reflects management’s attempt to build a more agile and decisive “central command.” However, beneath this seemingly orderly deployment lies FAW’s undeniable sense of urgency amid the tidal wave of the new energy era.

Is simply adjusting the leadership structure enough for this behemoth to truly accelerate its electrification journey? Or, to put it another way, what critical elements are still missing in FAW’s electrification strategy?

01

Volkswagen and Toyota “Lagging” in Electrification

Profit Generators Become Transformation Challenges

The underlying logic of this personnel realignment is a profound reshaping of the relationship between “central command” and “field operations.” By freeing group executives from the day-to-day management of a single joint venture, the goal is to reorganize the “strategic headquarters” and focus efforts on overcoming the lagging electrification transition.

Among these moves, Chen Bin’s return holds the most symbolic weight.

As a Group Vice President, his previous dual role as General Manager of FAW-Volkswagen was more akin to “frontline supervision” during a transitional period. In the era dominated by fuel vehicles, FAW-Volkswagen and FAW Toyota were undeniable “cornerstones” for the group, delivering massive profits and market share. However, entering the new energy era, these once-glorious sectors have inadvertently become the heaviest burdens during the “elephant’s turn.”

Take FAW-Volkswagen as an example. Despite leveraging Volkswagen’s global MEB platform to launch ID.-series electric models, in China’s fiercely competitive auto market, they merely qualify as “middle-of-the-pack performers.”

Compared to Tesla’s minimalist approach and the extreme intelligence of Chinese newcomers, the Volkswagen ID. series exudes stability but lacks innovation. In 2024, SAIC Volkswagen’s ID. family sold 130,000 units annually, but the stark contrast with its dominant fuel vehicle era underscores its weakness in the intelligent pure electric segment.

FAW-Audi’s situation is equally precarious. Although new models like the Q6L e-tron are poised for launch, in the high-end electric market, Audi’s voice is gradually being drowned out by local competitors like NIO, Li Auto, and HarmonyOS Intelligent Mobility. Sales data for 2024 reveals that out of 610,000 vehicles sold, fuel vehicles accounted for 550,000 units—over 90%. This structural lag casts a shadow over the brand’s future.

FAW Toyota’s electrification path has been even more turbulent. Toyota once dominated globally with its hybrid technology, but in China’s aggressive pure electric arena, the gap between sales and reputation of the bZ series proves that past successes are hard to replicate.

As these two “profit engines” show signs of fatigue in the electric racing track, anxiety at the group level has naturally reached its peak.

Chen Bin’s return to headquarters to lead marketing and overseas operations sends a clear signal: FAW is no longer satisfied with passively accepting technological inputs from joint venture partners. Instead, it aims to build a unified, efficient operational system at the group level to reshape market positioning for all its brands in the new energy era.

Dispatching sales veteran Dong Xiuhui to FAW-Volkswagen resembles a “precision airdrop.” The group hopes his seasoned market touch will revitalize Volkswagen’s electric vehicle presence in China with more locally attuned marketing strategies.

This adjustment is a reluctant “self-redemption.” It officially declares that the era of relying on joint venture profits is over. FAW must face the harsh reality: yesterday’s champions, if they can’t keep pace with the times, will eventually become tomorrow’s obstacles.

02

The Collapse of the “Partner Ecosystem”

A Misguided Dream of Shortcuts

Whenever discussing FAW’s “absence” in electrification, the chapter of “collectible-style” collaborations during that period is an inevitable bitter footnote.

Between 2018 and 2020, facing the tsunami-like impact of new forces, FAW didn’t choose immediate self-evolution but attempted to hedge crises through a “wide-net” shortcut approach. During this strategic anxiety phase, FAW brought in a host of new faces like Byton, Borqun, Xinte, Qingxing, and Yudo, hoping to achieve overtaking through external alliances.

The logic seemed self-consistent: FAW would leverage its deep manufacturing heritage, supply chain endorsement, and highly precious production qualifications to empower these new forces’ “blueprints.” In return, FAW hoped to acquire intelligent genes, internet thinking, and a ticket to the future at low cost and high efficiency.

However, what was once seen as a “gamble of trading money for time and factories for ideas” ultimately proved to be a grand narrative built on sand. Most automakers on FAW’s electrification collaboration list have now become industry “epitaphs.”

Byton once dazzled at CES with its 48-inch shared full-screen display but ended up nailed to the pillar of shame for “burning 8.4 billion yuan without producing a mass-produced car.” In 2021, its affiliated company Nanjing Zhixing declared bankruptcy liquidation, and that splendid screen ultimately failed to illuminate FAW’s electrification path.

Borqun and Yudo fared no better. The former, claiming to benchmark Tesla, collapsed rapidly after its capital chain snapped, entering a protracted bankruptcy process from 2022. The latter, an early “dual-qualification” flag-bearer, also disappeared in the fierce battle due to its product power’s generational lag.

Xinte and Qingxing, once hailed as “special forces” automakers, didn’t even stir a few ripples in the Chinese auto market before being declared out of the race. In this long list of collaborations, except for the surviving Leapmotor, nearly all other partners collapsed.

This “collectible-style” collapse laid bare FAW’s strategic confusion during the initial transformation phase. It essentially represented a profound path dependency, attempting to hasten the future through simple “grafting” of capital and manufacturing while neglecting the underlying logic of new energy vehicle competition. Auto manufacturing is not a single-point breakthrough of a cool concept but a full-link reconstruction from underlying R&D, product definition to user operations.

In this mismatched relationship, while FAW provided a “body” that could rival the industry, these partners failed to inject a “soul.” Most projects ultimately degraded into unappetizing yet hard-to-abandon OEM businesses, failing to internalize any core technological methodologies within FAW while leaving behind an industry embarrassment of “collapsing one partner after another.”

This costly trial and error bought FAW an expensive outdated ticket during the most critical strategic window.

03

The “Double Dilemma” of Independent and Joint Ventures

Why Is the Elephant’s Turn So Difficult?

After external collaborations hit a wall, FAW had to turn its ship around and redirect more energy internally. However, both the arduous breakthrough of independent brands and the defensive pressure from joint venture sectors clearly convey to the outside world the heaviness and stumbling of this “giant elephant’s turn.”

In terms of resource investment, FAW is undoubtedly a paragon of “not lacking money.” FAW-Volkswagen alone has invested over 10 billion yuan in electrification transformation and announced future annual R&D intensity exceeding 18 billion yuan. At the group level, it has unfurled the strategic banner of “All in,” planning four new energy platforms covering all sizes.

However, this nearly “gambling” capital injection hasn’t stirred equivalent waves in the market.

A mere 2.5% market share in 2023 and the vast chasm between autonomous new energy sales and the million-unit target by 2025 paint a harsh picture: on the new energy track, money doesn’t directly translate to speed. A “structural slowness” rooted in the huge organization’s physique and historical inertia has become FAW’s most concealed enemy.

As the “eldest son” and brand totem of the autonomous landscape, Hongqi’s electrification transformation, while notable in growth rate, still appears “inadequate” when placed against the group’s grand KPIs.

To date, Hongqi hasn’t produced a “phenomenal” product capable of defining a market segment like the Li Auto L series or Seres M series. Within its product lineup, the inertia of the fuel vehicle era still lingers, with visible generational gaps in intelligent experience and the core dimension of “software-defined vehicles” compared to first-tier new forces.

The two major joint venture “profit engines” under FAW have fallen into a “foreign aid dilemma.”

Both Volkswagen’s ID. series and Toyota’s bZ series are compromise products under global platforms. These products, defined with global aesthetics in mind, always seem a step slower in responding to Chinese users’ most desired features like “refrigerators, TVs, and sofas” as well as advanced intelligent driving needs.

Although FAW-Volkswagen has planned a vast catch-up blueprint, amidst competitors’ “semi-annual iteration” wartime rhythm, the joint venture’s lengthy decision-making chain has become its most fatal constraint.

A deeper issue lies in FAW’s limited involvement in core foundations like three electric systems and algorithms during long-term collaborations, having mostly played the roles of “assembly plant” and “salesperson.” This lack of dominance means that even when the window of opportunity is clear, it’s difficult to drive products toward thorough “genetic mutations.”

After completing the “personnel reshuffle” in top-level design, what exactly is still missing in FAW’s electrification journey? This isn’t merely a course correction solvable by changing a few “captains.” Instead, it requires a comprehensive reshaping of products, mindset, and structure.

The primary deficiency lies in lacking a “soul” product that can decide the outcome.

Surveying the current new energy landscape, BYD has built moats with its “extremely hardcore” three electric technologies, while Tesla harvests faith with its disruptive “minimalism.” In contrast, FAW’s new energy matrix, while steady in various indicators, lacks a “must-buy, unforgettable” label.

In a highly homogeneous red ocean, without a phenomenal blockbuster to ignite the market, all marketing slogans appear pale and powerless.

A deeper crux lies in the “internet user thinking” that hasn’t touched the soul.

The collapse of past “collectible-style” collaborations essentially stemmed from FAW’s attempt to dismantle new auto manufacturers’ B2C strategies using traditional manufacturing’s B2B logic. However, in the era of software-defined vehicles, vehicle delivery is no longer the endpoint of business but the starting point of relationships.

FAW needs more than just a few apps or superficial user communities; it requires an organizational structure earthquake from R&D to service ends. Unless it breaks down the cold and thick “departmental walls” and establishes user-centric practical combat teams, rebuilding this soft power is even more challenging than reconstructing a physically super factory.

The hardest chasm to cross is the courage for “radical self-reform.”

To this day, joint venture fuel vehicle businesses still contribute bountiful profits, serving as both the blood for maintaining the huge body’s operation and a “sweet burden.” When aggressive electrification strategies threaten to shake the current profit foundation, internal resistance from vested interests is predictable.

Chen Bin and other executives withdrawing from joint venture frontlines to return to the center sends an unambiguous signal: FAW is attempting to sever those intricate interest entanglements, allowing the group’s “brain” to jump out of local comfort zones and forcibly pull the company toward a turn with a more objective and resolute stance.

Chen Bin’s return, Dong Xiuhui’s reassignment, and Nie Qiang’s southern move are all part of FAW’s self-rescue attempts in deep waters. This adjustment makes the “brain” more robust and the “battle zones” more pragmatic, but it’s merely the prologue to a prolonged battle.

On the future intelligent electric vehicle gaming table, can FAW secure a core seat? Can this behemoth regain its past dignity on the turbulent new navigation path? The answers still hang in the balance at those turning points filled with variables.

- END -