8.32 Million Vehicle Exports: No Need to Worry About the 'Closure of the Growth Window'

![]() 02/09 2026

02/09 2026

![]() 451

451

Lead

Introduction

The true key lies in transitioning from mere product exports to the export of standards and capabilities.

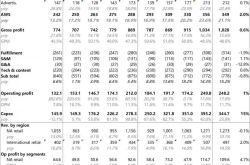

Last Thursday, the China Passenger Car Association (CPCA) released the precise figure for China’s vehicle exports in 2025: 8.324 million units.

To put this number into perspective—in all of 2025, the United States, the world’s second-largest automotive market, sold 16.391 million new vehicles. In comparison, China’s annual vehicle exports could fill nearly half of this global second-largest market.

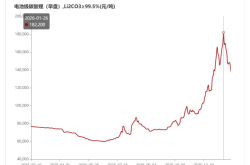

Since 2022, China’s vehicle exports have entered a phase of rapid growth.

In 2022, China surpassed Germany to become the world’s second-largest exporter with 3.32 million units; in 2023, it overtook Japan to rank first globally with 4.91 million units exported; and in 2024, it further expanded its lead with 6.41 million units, reaching 85% of the combined exports of Japan (second place) and Germany (third place). Last year, as major automakers doubled down on their “going global” strategies and due to delays in new energy and intelligent transformation by key Japanese and German competitors, China’s automotive industry took another major leap forward.

From the peak, the view is limitless. But at the same time, it’s hard to avoid the chill of heights.

However, amidst the celebrations, we must not ignore risks and crises. Given the current global environment, the rise of trade protectionism is an inevitable trend, and the narrative of four consecutive years of high growth has already encountered sustainability issues in multiple regions.

Therefore, on the eve of the Year of the Horse, while celebrating the previous year’s achievements, there is also an unavoidable concern about “how long the red flag can fly.”

As part of the Auto Business Review’s year-end series, this article will elaborate on the conditions China’s automotive exports faced in different global markets over the past year. Only by clearly perceiving these shifts can we fully analyze opportunities and risks and explore paths to build a new development paradigm from these “heights.”

01 The Russian Market: A Sharp Decline Followed by a Rebound

Let’s first examine Russia, which saw the most dramatic changes in 2025.

According to CPCA Secretary-General Cui Dongshu, Chinese companies exported a total of 583,000 vehicles to Russia in 2025, second only to Mexico’s 625,000 units. The reason we start with the second-place market is that in 2024, Chinese automakers exported nearly 1.16 million vehicles to Russia. By comparison, last year’s figure represents a near “halving.”

Overall, the Russian market followed a volatile trend in 2025—declining first before rebounding. In the first half of the year, China’s vehicle exports to Russia plummeted by a staggering 62.5% year-on-year, though conditions improved in the second half. This sharp fluctuation caused Chinese brands’ market share in Russia to drop from 26% in 2024 to just 15% within a year.

After rapid expansion from 2023 to 2024, Chinese companies now face growing policy risks in the Russian market.

First, vehicle scrappage taxes increased by 70–85% starting in October 2024, with plans for annual increases. Simultaneously, Russia tightened and retroactively collected transit trade taxes through Central Asian countries, closing off “gray” import channels. Since last year, Russia has also raised import tariffs to 20–38%. Legally, the Russian government now mandates that every imported model must pass OTTC certification by Russian domestic laboratories—a lengthy and costly process.

Currently, Russia’s domestic automotive consumption is also affected by high inflation and ruble volatility. Its benchmark interest rate remains at a lofty 21%, driving annualized auto loan rates as high as 30% and severely suppressing demand. As the Russia-Ukraine conflict shows signs of winding down, some Russian consumers anticipate the return of Japanese and European brands to the market and are delaying purchases amid current policy and economic uncertainties.

Beyond macroeconomic factors, the core objective of Russia’s policy shifts over the past year is not merely to curb foreign—particularly Chinese—automotive brands but goes beyond simply increasing fiscal revenue. The deeper intent is to force foreign automakers into local production to rebuild Russia’s automotive industrial system and protect homegrown brands like Lada.

From Russia’s national interest perspective, avoiding over-reliance on a single country in a critical industry is only natural. Additionally, as signs emerge of an end to the Russia-Ukraine conflict, ensuring employment for demobilized Russian military personnel is a serious consideration for the current government.

From the perspective of Chinese companies, the decision lies in whether to comply with Russian official demands by deploying or increasing local production capacity or, given concerns about long-term market stability, to gradually scale back or even exit. The initiative rests with the companies themselves.

02 The Mexican Market: Sudden Turmoil

Unlike Russia, the Mexican market surged from 340,000–386,500 units (depending on the source) in 2024 to 625,000 units in 2025—a roughly 70% increase. When combined with the trend in Russia, it feels like “when one side dims, the other brightens.”

But unexpected turmoil struck at year-end.

In late 2025, the Mexican government suddenly announced that starting New Year’s Day, it would impose tariffs of up to 50% on vehicles and goods originating from countries without free trade agreements, including China. Officially, Mexico claimed this was to boost fiscal revenue and protect domestic industries. However, the deeper reason was to demonstrate loyalty to the current U.S. administration by aligning with U.S. trade policies.

After all, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) includes a “rules of origin” requirement mandating that 75% of automotive components must come from North America to qualify for zero tariffs on exports to the U.S.

From our perspective, such arbitrary tariff hikes are clearly provocative. However, given Mexico’s deep economic integration with the U.S.—and its inability to match Canada’s industrial base and economic strength—this submissive stance is not surprising.

These tariffs will inevitably impact Chinese automakers’ market position in Mexico. First, reliance on direct vehicle exports will become far less profitable due to soaring tariff costs. Second, using Mexico as a springboard to supply the U.S. market will become unsustainable in the short term.

So, how will Chinese companies respond? Recently, an insider from a Chinese automaker exporting to Mexico told the author that given domestic firms’ supply chain and cost controls, tariffs of up to 40% pose “no pressure,” and even tariffs of 60–70% would still leave their products competitive.

That said, Chinese companies did not go global out of charity. Whether to relocate parts of their supply chains to comply with Mexico’s “rules of origin” or to increase local vehicle production capacity hinges on each company’s risk-reward calculations.

03 The European Market: Gradual Stabilization

Compared to the risk-laden Russian market and Mexico’s year-end turmoil, Europe—once a hotspot—is gradually cooling.

From late 2024 through most of 2025, Chinese automakers in Europe experienced a rollercoaster ride. Since 2023, leveraging new energy powertrains and superior intelligence, Chinese brands saw explosive growth in Europe. However, their rapid market penetration alarmed local automakers, prompting multiple countries and even the European Parliament to consider anti-China tariff measures.

After intense negotiations and efforts from late 2024 through the first half of 2025, the EU made key progress on tariffs for Chinese-made new energy vehicles, shifting from imposing high anti-subsidy duties to solutions centered on a “minimum price commitment” mechanism. Currently, companies like SAIC, BYD, Geely, NIO, and XPeng operate normally in Europe under this framework, which allows for “higher prices, lower taxes.”

Minimum import prices are set in two ways: either based on the vehicle’s CIF (cost, insurance, and freight) value during the investigation period plus the anti-subsidy tax that should have been levied, or referenced against the prices of similar unsubsidized battery electric vehicles in the EU market.

For Chinese companies, accepting price commitments means forgoing low-price competition and constraining vehicle pricing. However, the benefits are clear—taxes that would have gone to the EU government can now be retained as profit, while stable and predictable market access conditions facilitate long-term planning and brand-building.

More importantly, minimum price restrictions prevent the kind of extreme price wars that have plagued China’s domestic market from spreading to Europe. For many Chinese automakers struggling domestically, Europe offers not only relief but higher profit margins.

BYD is a prime beneficiary, exporting over 180,000 vehicles to Europe last year, including 80,000 units of the European-spec Song PLUS alone.

However, in today’s environment, no industry or company can expect true “calm.” As one wave subsides, another rises: the EU is now developing a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), or “carbon tariff.”

Currently, CBAM targets steel, aluminum, and other raw materials, but calculations show that if implemented, each new energy vehicle exported to the EU could face over €200 in additional carbon costs due to steel and aluminum components. Vigilance is essential.

04 Southeast Asia: The “Anchor” of Overseas Expansion

The Russian, Mexican, and European markets all experienced sharp policy shifts in the short term. Whether for better or worse, such volatile business conditions are undesirable. In contrast, the Middle East, Asia-Pacific, and South American markets performed relatively stably last year.

The Asia-Pacific region, being closer to China, includes countries like Thailand and Malaysia with established industrial capabilities, making it a frontline for China’s automotive “going global” strategy over the past decade. By 2025, years of cultivation are beginning to pay off.

Led by pure electric vehicles from multiple brands, Chinese automakers saw sustained rapid growth in key Southeast Asian markets like Thailand and Indonesia last year. Sales in Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines surged in the first half, with Chinese brands capturing over 90% of Indonesia’s pure electric vehicle market.

Due to proximity and relatively easy supply chain integration, Chinese companies in Southeast Asia are rapidly shifting from direct vehicle exports to localized production. By 2025, at least seven Chinese automakers had built factories in Thailand, with annual capacity exceeding 600,000 units. BYD’s Thai plant has become a key hub for ASEAN and right-hand-drive markets.

As complete vehicle brands (finished vehicle brands) expand overseas, component suppliers follow. Battery makers like CATL and Sunwoda, along with interior and mold manufacturers, have set up factories across Southeast Asia. The sight of entire automotive supply chains “going global” together was remarkable in 2024–2025.

Interestingly, many Chinese companies rapidly deployed in Southeast Asia by acquiring Japanese automotive assets—their main competitors in the region. Meanwhile, Japanese automakers’ local factories, seeking cost reductions, are realistically sourcing more components from Chinese producers in Thailand.

Given its controllability, the Southeast Asian model also includes technology transfers, joint ventures, and even co-building industrial ecosystems and talent pipelines. A prime example is Geely’s revival of Malaysia’s national brand Proton. The establishment of the China-ASEAN New Energy Vehicle Education-Industry Integration Consortium is also training and supplying local professionals.

05 The Middle East, Australia, and South America: Temporary Havens

If we consider the entire Middle East as one market, Chinese brands exported 826,000 vehicles there last year, including 128,000 new energy vehicles—a 132% year-on-year increase. While some vehicles come from local production bases, increasing numbers are now sourced from nearby Southeast Asian factories.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE were the region’s largest national markets, with sales of 285,000 and 197,000 units, respectively. These countries boast strong purchasing power, and local consumers’ trust in Chinese brands is rising significantly.

Notably, high-end Chinese SUV models have gained remarkable acceptance in the Middle East, capturing up to 18.6% of niche market segments last year. Some brands, relatively obscure in China, enjoy local recognition.

These trends reflect how Chinese automotive exports have shifted from traditional cost-performance advantages to technological leadership, driven by new energy and intelligence.

Last year, Australia’s total automotive market reached 1.241 million units. Chinese automakers sold 252,000 vehicles there, boosting their market share from roughly 14% in 2024 to 20.4%. China is now Australia’s second-largest vehicle source country.

New energy passenger vehicle exports to Australia hit 111,000 units, up 63.6% year-on-year. Given Australia’s geography, plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) saw particularly strong growth, surging by about 130.9%.

Australian consumers have a strong preference for SUVs and pickups, which account for over 80% of the market. Chinese automakers excel in these segments: BYD’s Shark PHEV pickup sold about 18,000 units in 2025, breaking into a market long dominated by Ford and Toyota. Great Wall Motors has built a solid reputation for its Haval and Tank series SUVs, which offer strong off-road capability and reliability.

Finally, we must discuss Brazil. In 2025, Chinese automakers achieved a critical transition in Brazil from participants to leaders, shifting strategic focus from direct vehicle exports to deep localization.

Chinese brands sold over 260,000 units in Brazil last year, capturing nearly 12% market share. More significantly, BYD and Great Wall Motors opened factories in Bahia State and São Paulo in July and August, respectively.

Additionally, Geely partnered with Renault in Brazil to form a joint venture, entering the market through an asset-light model.

The current Brazilian government has clear ambitions for its automotive industry, employing a classic “carrot and stick” approach to encourage foreign localization. Through the “Mover Program,” it offers tax incentives while gradually raising import tariffs on electric vehicles to 35% by July this year. This directly prompted Chinese automakers to shift from tariff-window export rushes to local production, establishing substantial manufacturing bases in the Western Hemisphere’s largest southern nation.

06 A World Where Risks and Opportunities Coexist

A brief summary of the situations faced by China's auto exports in various regional markets over the past year will likely reveal to all of you that, whether in regions encountering problems or in markets where development and layout (layout) are currently proceeding smoothly, there are actually overt and covert plans to guide or compel the localization of production capacity and even supply chains.

The difference lies in the fact that some countries adopt hardline measures, directly imposing tariffs, while others use relatively gentler approaches, such as guidance or incentives.

However, this is also a problem that all global automotive giants have faced when expanding beyond their home markets. Especially in the current context of rising global trade protectionism, governments worldwide are attempting to anchor multinational trade, which involves the most jobs and profits, locally in order to safeguard their national interests.

Whether it's Mexico's 'tariffs forcing localization' or Europe's 'green barriers forcing compliance upfront,' regardless of the profound backgrounds behind these measures, they all ultimately point to the same common goal: to compel multinational automakers engaged in trade with them to gradually shift from simple export of complete vehicles to localized production, establishment of local supply chains, and R&D systems in the target market or region.

Let's return to the initial question, which is the main theme of this article—by reviewing the situations faced by Chinese automobiles 'going global' in various regional markets last year, we analyze how long the 'window of opportunity' left for us will last.

The answer is actually very clear. From the perspective of narrowly defined auto export statistics, with the current trend of deglobalization and the escalation of trade barriers in various countries, the 'window' is actually closing. The wave of auto exports that began in 2022 will come to a halt within the next one to two years and see a regression in statistical data.

However, this does not mean the end of the strategy for Chinese automobiles to go global.

In Mexico, Chinese companies are exploring a 'tiered layout,' trying to place the lowest value-added assembly processes locally while keeping high value-added components such as chips and motors in China. At the same time, they are actively forming alliances with North American suppliers to meet 'compliance' with rules of origin. In Europe, they need to actively respond to environmental regulations, transforming compliance with requirements such as carbon footprint and material traceability from cost items into competitiveness.

The history of the global automotive industry thus far shows that the ultimate competition among technology, brand, and systems will be a comprehensive contest of brand value, continuous technological innovation, and global operational systems. This requires automakers to build comprehensive sales and after-sales service systems in overseas markets, strengthen overseas intellectual property layout (layout), and complete the transformation from 'local companies' to 'global companies.'

In the coming years, figures for local production and local sales in other markets will take over the baton from the growth in complete vehicle exports, driving Chinese automobiles to continue conquering global markets and bringing a steady stream of profits back to the companies.

In summary, Chinese auto exports indeed demonstrate resilience, with 'brightness on the west side when the east side is dim' amidst dynamic adjustments. Policy fluctuations in different regional markets are not the endpoint but are instead accelerating the profound transformation of Chinese automakers from product exports to the export of standards and capabilities.

The road ahead is filled with both challenges and opportunities, and deep localization and true global operational capabilities will be the keys to winning this protracted battle. There's no need to worry about useless things; each of us should simply strive to do everything we ought to do well!

Editor-in-Chief: Li Sijia Editor: Chen Xinnan

THE END