China's Infrastructure Expansion into Southeast Asia

![]() 12/25 2024

12/25 2024

![]() 671

671

By | Hu Mo

Edited by | Yang Xuran

In July of this year, the Deputy Director of the State Railway Bureau of Thailand announced that the State Railway Bureau Committee had approved the second phase of the China-Thailand government cooperation high-speed rail project. This phase spans 357.12 kilometers and carries a total investment of 341.35142 billion baht. The project will be submitted to the cabinet meeting for deliberation in January 2025 and is expected to commence operations in November 2031.

Rumors online suggest that the projected operation date of the project has been advanced from 2031 to 2029, even before it was formally submitted to the cabinet for approval.

The first phase of the China-Thailand railway project, connecting Bangkok, the capital of Thailand, with Nakhon Ratchasima, is anticipated to open in 2028. High-speed trains departing from Kunming will reach Bangkok, Thailand, at speeds of 250 km/h. Upon completion of the second phase, a critical railway corridor linking Thailand, Laos, and southwestern China to the Gulf of Thailand will be formally established.

The China-Laos Railway, officially opened in 2021, has emerged as a hallmark case of Chinese enterprises deeply engaged in Southeast Asian infrastructure. Costing approximately US$6 billion and spanning 1,000 kilometers, this project enables travel from Kunming to Vientiane, the capital of Laos, in as little as 10 hours.

Further south, despite two government changes, China successfully secured the 665-kilometer infrastructure project for the Malacca-Dongguan Railway. Similarly, the Jakarta-Bandung High-Speed Rail in Indonesia was also awarded to China over Japan, despite facing opposition.

China's infrastructure expansion into Southeast Asia connects southwestern China with countries like Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Malaysia through railways, enabling many landlocked nations to participate in the global logistics system. This significantly reduces international transportation costs and time.

Beyond railways, China's infrastructure in Southeast Asia also encompasses water conservancy and port projects. These projects are of great significance to China's economy: on the one hand, as China's urbanization rate nears completion, this expansion opens new opportunities for China's infrastructure capacity and construction machinery; on the other hand, improved transportation facilitates more efficient economic exchanges between China and Southeast Asian countries, allowing more Chinese industries and products to enter ASEAN markets.

Mining Gold: Replicating China's Past Success

A comparison of the ten Southeast Asian countries (Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, and Brunei) with China reveals that Southeast Asia's land area is 46% of China's, and its population is approximately 48% of China's. However, its railway mileage and power generation capacity are less than 20% of China's, and its highway mileage is only about 30% of China's.

Notably, the railway and road density indicators of the Philippines, Laos, Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam are significantly low. For instance, the Philippines' railway development dates back to narrow-gauge railways built by American colonizers in the early 20th century, primarily for transporting minerals and resources. Today, these railways are outdated and unable to meet current economic development needs.

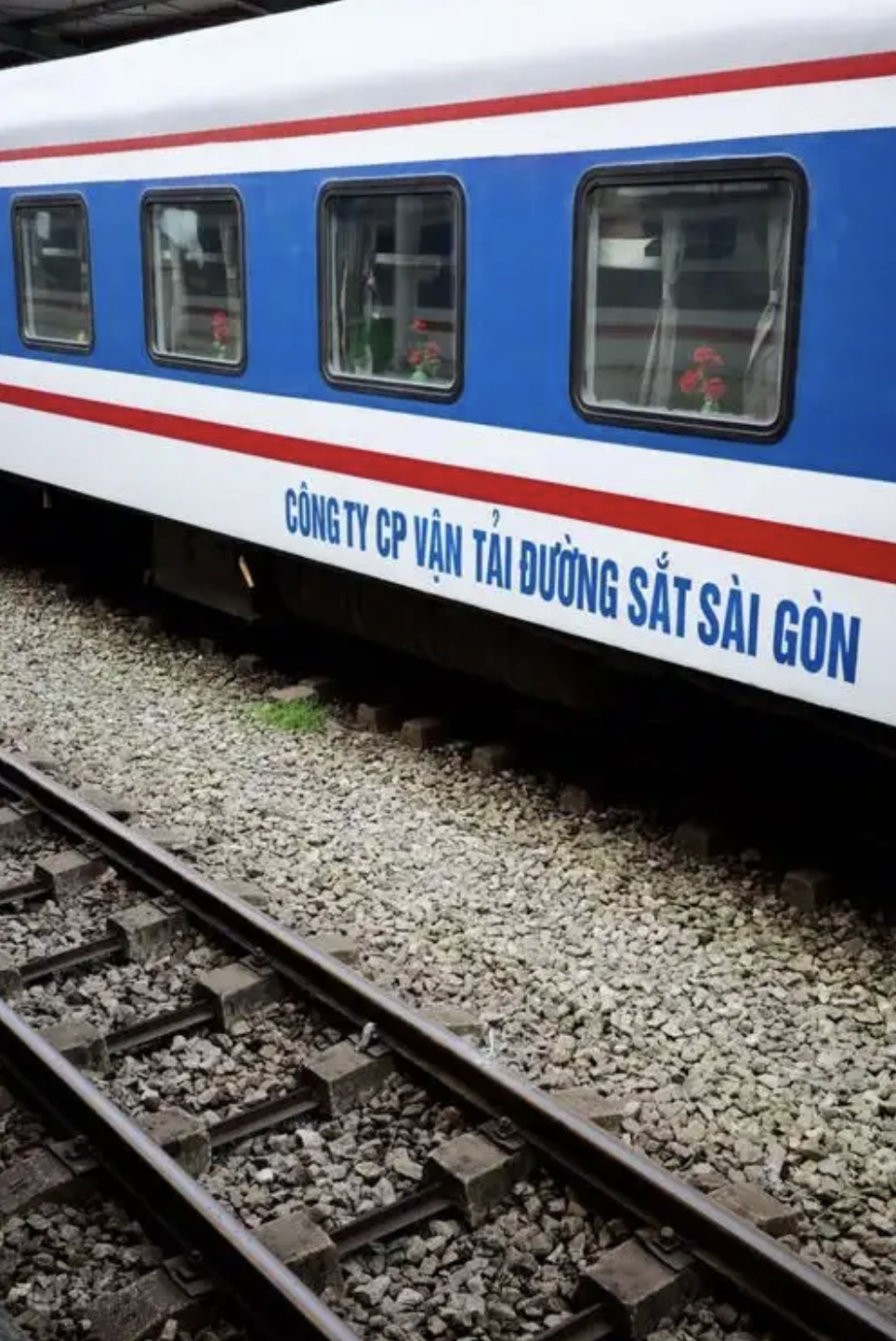

Vietnam's situation is also unfavorable. In the 39 years since its "Doi Moi" (renovation) policy in 1986, Vietnam has only constructed 500 kilometers of meter-gauge railways. For a Southeast Asian country spanning over 330,000 square kilometers, this accomplishment is underwhelming. Such meter-gauge railways have limited carrying capacity, with trains able to carry a maximum of 30 wagons, compared to over 90 wagons for China's freight railways. Vietnam's railway infrastructure lags behind China by at least half a century, significantly hindering local economic development.

Meter-gauge railways in Vietnam

Similarly, according to Thailand's Ministry of Transport, Thailand's railway network spans approximately 5,013 kilometers, of which 4,801 kilometers are meter-gauge, with limited capacity.

Indonesia's situation is even worse. As an archipelagic country, the primary modes of transportation are waterways and air travel, with slow railway development. Before the Jakarta-Bandung High-Speed Rail, travel between the two cities relied on railways built over a hundred years ago, with a speed of only 50 km/h, far from meeting the travel needs of the combined population of around 12 million residents.

Despite these challenges, the people of Southeast Asia also have an urgent desire to enter modern society and a genuine need to improve their lives.

Beyond transportation, the demand for housing in many regions of Southeast Asia has been robust in recent years. The house price-to-income ratio in many areas has approached or even surpassed China's levels. For example, residents of Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, need approximately 25.3 years of salary to afford a house, longer than in Hong Kong; similarly, residents of Manila, Philippines, need about 25 years of salary.

Considering that the urbanization rates of many Southeast Asian countries are still at the levels of China a decade or two ago, housing demand in many regions of Southeast Asia remains largely unsatisfied, offering hope for replicating China's past three decades of "infrastructure driving real estate, real estate driving infrastructure" model.

Previously, CICC analyzed Southeast Asian infrastructure using the ratio of fixed capital formation to GDP and found that most countries range between 20% and 30%, significantly lower than China's perennial level above 40%. As one of the world's most densely populated regions, Southeast Asia's infrastructure has lagged behind economic development, to some extent impeding local growth.

Long-term lagging railway infrastructure in the Philippines

Currently, many Southeast Asian countries have recognized this issue and have begun to vigorously develop infrastructure using fiscal funds. Many countries have formulated short-term or long-term infrastructure plans.

For example, after Indonesia's capital moves from Jakarta to East Kalimantan Province, significant construction will take place for many years, potentially becoming the largest infrastructure project in Southeast Asia.

Equipment: Chinese Equipment Expands into Southeast Asia

According to the General Administration of Customs, China's construction machinery exports reached $48.552 billion last year. Among major economies, Southeast Asia was the second-largest export destination for Chinese construction machinery, after Africa and Latin America, with exports totaling $7.16 billion.

ASEAN is not only a key region for the Belt and Road Initiative but also China's largest trading partner. Especially with the implementation of the RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership) in early 2022, Chinese enterprises have benefited from favorable policies regarding tariffs and trade facilitation.

XCMG equipment at the Thailand Construction Machinery Exhibition

These favorable policies have enabled Chinese construction machinery enterprises to more smoothly integrate into the local market.

For example, in the Indonesian market, XCMG has participated in various key projects such as Indonesia's tallest building, the Jawa-7 coal-fired power plant project, the tunnel project of the Gatigedi Dam in Indonesia, and the second phase of the Jakarta-Bandung High-Speed Rail. On the one hand, XCMG's products offer high cost-effectiveness; on the other hand, through in-depth research, XCMG began providing customized products tailored to the local mountainous, humid, windy, and hot environment.

Sany Heavy Industry entered the Southeast Asian market earlier, establishing offices in the Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, and other places as early as 2007. In August 2022, Sany's first overseas "lighthouse factory" in Indonesia commenced production, signifying that Sany Heavy Industry has brought its advanced high-end manufacturing capabilities to Southeast Asia and achieved localized production.

Media coverage of Sany Heavy Industry's Indonesian factory

Liugong, headquartered in Guangxi, also has a significant presence in the Southeast Asian market due to its geographical proximity, exerting considerable influence in Vietnam, Thailand, Myanmar, and other regions. It has participated in key projects such as the China-Laos Railway, Jakarta-Bandung High-Speed Rail, the Phnom Penh-Sihanoukville Expressway in Cambodia, the China-Myanmar Oil Pipeline, and the Cagayan de Oro International Airport in the northern Philippines.

It has not been easy for Chinese construction machinery to achieve its current position in Southeast Asia, which was once dominated by Japanese enterprises. After the bursting of Japan's real estate bubble in the last century, Japanese manufacturing industries sought overseas markets for growth. With their high-quality products, they naturally dominated the Southeast Asian construction machinery market.

In recent years, the rise of Chinese construction machinery has gradually eroded Japanese brands' market share in Southeast Asia, forcing them to make adjustments. For example, to compete with Chinese enterprises, Komatsu has developed more energy-efficient hybrid hydraulic excavators. Hitachi Construction Machinery has established a new parts manufacturing plant in Indonesia to supply medium and large hydraulic excavator parts to Southeast Asia, achieving localized production to improve efficiency.

Japanese construction machinery remains highly competitive in Southeast Asia

Forcing competitors to improve is also a demonstration of strength. So, why have Chinese enterprises been able to gradually secure various infrastructure projects in Southeast Asia while challenging Japan's dominance in the construction machinery sector? Relying solely on "cheapness" is clearly insufficient.

Challenge: It Can Only Be China

China has a long history of exchanges with Southeast Asia. As early as the Han Dynasty, Zhang Qian's diplomatic mission to the Western Regions opened up trade routes from Sichuan to Myanmar and then to ancient India, known as the "Southern Silk Road" or the "Shu-Shen-Du Route".

Chinese tea was exported to various parts of Southeast Asia through these routes, while Southeast Asian ivory, rhinoceros horns, and other specialties also entered China.

The Southwest Silk Road, also known as the "Shu-Shen-Du Route"

In modern times, due to various reasons, there have been some rifts between China and Southeast Asia. For a long time, Southeast Asia has been one of the most important overseas markets for Japanese enterprises. Under American dominance after World War II, Japan once cut off trade relations with China, leading to a one-third loss in total trade volume. To compensate, Japan turned its attention to the densely populated and resource-rich Southeast Asian market.

Regarding war reparations, Japan chose to compensate Southeast Asian countries in the form of labor, equipment, and technology, paving the way for Japanese enterprises to enter the region. Leveraging their technological advantages and the benefits of the times, Japan participated in the development of projects such as iron ore mining in Malaysia, oil exploration in Indonesia, and copper mining in the Philippines.

Due to the significant preferential policies granted by the Japanese government to local enterprises, Japanese enterprises were able to encroach on the survival space of Southeast Asian local enterprises at a low cost, often viewed by locals as a form of "economic aggression".

Later, as Japanese enterprises continuously improved their corporate social responsibility management, they also established associations to monitor their performance in fulfilling social responsibilities locally, gradually improving the perception of Japanese enterprises among Southeast Asians.

Overall, Japanese enterprises' advantages in Southeast Asia mainly lie in their long-term presence and involvement in social responsibility management, making their products an indispensable part of Southeast Asian people's lives and creating an ecosystem for market expansion in collaboration with banks and associations.

Southeast Asian society values the social responsibility performance of commercial enterprises

Therefore, while it is undoubtedly challenging for China to challenge Japan's position in Southeast Asia, it is not impossible.

For example, during the bidding process for the Jakarta-Bandung High-Speed Rail, although China's proposal was $1 billion higher than Japan's, Japan was only willing to provide a 75% low-interest loan, with the remaining 25% to be funded by Indonesia. In contrast, China offered a full loan repayable over 50 years, without requiring a debt guarantee from the Indonesian government and with a shorter construction period than Japan's proposal. Naturally, the Indonesian government chose China.

Certainly, China's endeavors are not altruistic. For instance, by undertaking the Jakarta-Bandung High-Speed Rail project, China secured the franchise rights to the high-speed rail, enabling it to recoup construction costs through profits generated from the service. Essentially, China's willingness to offer more favorable terms signifies a long-term investment in Indonesia's economy, whereas Japan's approach is more cautious.

For regions in Southeast Asia characterized by complex terrains, such as high altitudes in the north and lowlands in the south, interspersed with mountains and rivers, China stands out as the only country globally with the most extensive construction experience to draw upon.

In conclusion,

Drawing from Japan's previous development trajectory in Southeast Asia, infrastructure development often serves as a precursor for more companies to expand globally.

As infrastructure in Southeast Asia continues to improve and advance, local residents will develop new perspectives and understandings of Chinese enterprises, thereby paving the way for Chinese businesses to enter the vast Southeast Asian market. Without this process, given Japanese enterprises' dominant position in Southeast Asia, Chinese companies would face even greater competitive pressure.

However, examining the commercial trade relationship between China and Southeast Asia over a longer historical context reveals that it has long been a naturally complementary partnership. Despite some regression in recent years due to complex political factors, ASEAN has swiftly become China's largest trading partner, evidencing the economic complementarity between the two sides.

In the new era of global multipolar development, Southeast Asian countries harbor their own aspirations for growth and must weigh the interests and relationships among various partners. Robust infrastructure support is a crucial factor in China's influence within this region.