Alert | Humanoid Robots: 'Orders Galore, But Where Are the Robots?'

![]() 10/24 2025

10/24 2025

![]() 483

483

The "left hand to right hand" order phenomenon in the robotics sector is not a simple dichotomy of "good versus bad." Instead, it is a nuanced outcome shaped by specific stages of industrial development. Drawing parallels from the new energy vehicle (NEV) industry, such orders play an irreplaceable "stage value" role in technical validation and capacity expansion. However, as the industry transitions into large-scale commercialization, it must ultimately pivot back to the core of "real demand."

Editor: Lv Xinyi

Orders worth tens or even hundreds of millions are flooding in, signaling a robust response to the development of humanoid robots.

This surge in orders is not merely a short-term financial boost but a pivotal leap toward a virtuous cycle of growth. The funds from these orders can fuel further technological advancements, while the corresponding application scenarios provide an ideal platform for practical testing and optimization. This drives robots from merely "being able to do" tasks to "doing them well." These orders carry significant positive implications for both individual corporate development and the cultivation of the entire industrial ecosystem.

However, we must maintain a clear-eyed perspective amidst this seemingly positive wave of orders. Not everything is as it appears. There is a portion of "left hand to right hand" related orders intertwined within the market.

For instance, companies may establish subsidiaries in collaboration with other entities and then have those subsidiaries purchase their own humanoid robots. At best, this can be described as a "large order," but at worst, it raises serious questions. There are even "questionable orders" that are merely framework agreements with no signs of actual delivery or mention of delivery timelines in the disclosed information. (Party A: "Just buy it; I won't use it.")

Suddenly, the market is abuzz with the sound of orders, yet the robots themselves remain conspicuously absent.

It is crucial to clarify that in the early stages of the industry, not all related orders should be dismissed outright, nor should all involved companies be viewed as "connected entities." After all, humanoid robots at this stage require validation during their ramp-up period and urgently need a platform to showcase their capabilities. Related orders offer a low-cost avenue for both sides to engage in trial and error. Through collaboration with related parties, companies can swiftly gather operational data, iterate product solutions, and avoid the technical adaptation risks and market education costs associated with directly entering unfamiliar markets. Essentially, this is a "safety net" verification path in the early stages of the industry.

However, if related orders constitute an excessively high proportion or even become the dominant force in a company's order structure, their potential risks warrant caution. On the one hand, over-reliance on related transactions may lead to "specialization" in technical verification, where homogeneous demand in related scenarios fails to address the real pain points of a diversified market. This can easily result in the "dulling" of a product's marketization capabilities. On the other hand, the performance boost from related orders may create a "false prosperity," obscuring the true market demand boundaries of the industry and triggering the risk of blind expansion of low-end capacity and泡沫化 (bubble-like) risks.

In summary, while related orders may be enticing, one must not lose sight of the bigger picture.

Stage-Specific Demand: Related Orders Bridge the "Valley of Death"

"In the early stages of disruptive technology development, mainstream customers never choose to use disruptive products." - The Innovator's Dilemma. Throughout the history of human technological advancement, almost all disruptive products have had to endure a lengthy cultivation period of "technological exploration - scenario verification - scale explosion." From computer lab prototypes to desktop terminals in thousands of households, from policy-dependent new energy vehicles to market-driven popularity, emerging industries often face multiple dilemmas in their early stages, including "immature technology, high costs, and vague demand." They require both continuous R&D investment to break through bottlenecks and real-world scenario feedback to complete iterations, not to mention policy and capital support to navigate the "valley of death." Today's humanoid robot industry is precisely such a strategic and disruptive field that holds high hopes but is still in its infancy. However, in terms of product markets, ordinary households are unlikely to choose them in the short term, while industrial scenarios cannot yet compete with traditional automated equipment and robotic arms. Humanoid robots can only tap into sporadic "edge orders." This has led to a temporal misalignment between the strategic importance of humanoid robots and the maturity of industrial development, potentially slowing down the pace of industrial progress.

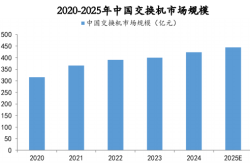

At this juncture, orders driven by non-real commercialization factors, such as industry investors, are needed to drive the deployment of humanoid robots in roles and learning within scenarios. History often repeats itself in surprising ways. We can first look back at the early stages of the new energy vehicle industry, where "left hand to right hand" related orders were a common phenomenon. Many early orders for some automakers came from internal group purchases (e.g., automakers supplying vehicles to their affiliated ride-hailing platforms) or locally driven related transactions (e.g., public transportation systems purchasing local new energy vehicle models). While these orders bore the mark of internal circulation, they played an irreplaceable role in the early stages: helping companies complete early capacity ramp-up, diluting R&D and manufacturing costs, and providing real-world scenario data support for technological iterations. This logic is highly consistent with the current related orders in the robot industry.

The robot industry is currently at a critical stage of "technical verification - early commercialization," and the rationale for related orders essentially aims to address many pain points in industrial development.

From a market demand perspective, the real consumer demand for humanoid robots has not yet fully erupted. If ordinary companies rely solely on market-driven orders, they may easily fall into a survival dilemma of "high R&D investment but low revenue returns." The bundled cooperation model of "investment + orders" provides companies with "lifesaving funds" to sustain technological R&D.

From an industry characteristic standpoint, the iteration cost of robot products is extremely high, often exceeding tens of millions or even hundreds of millions of yuan in R&D investment per unit. Current robot products are also non-standardized, making direct entry into an uncertain demand market highly risky. By leveraging framework orders or agreement orders from related parties, companies can significantly reduce trial-and-error costs through negotiated product parameter adjustments and deployments.

From an ecological niche perspective, companies currently holding large related orders are mostly players that have already secured or are vying for leading positions in the industry. Whether preparing for listings, meeting local industrial demands, or building industry influence, the chain of "orders - revenue - valuation - industry status" is a necessary path for companies to achieve long-term goals, with related orders serving as stepping stones along the way.

However, we must also recognize that the current core flow of orders is still concentrated on the B-side (business) and even the G-side (government), while the key to truly igniting the industry lies in when C-side (consumer) orders can surpass B-side orders. The current lack of opening in the C-side market fundamentally stems from technological bottlenecks, meaning robots still fall short in terms of "adequacy" and "ease of use," with precision, endurance, and interaction capabilities not yet meeting consumer expectations. Therefore, related orders have a certain stage-specific inevitability in the short term.

Beware of "Boiling the Frog in Warm Water"

The stage-specific significance of related orders reflects the industry's confidence in "taking a long-term view," but this does not mean overlooking the risks behind them. When related orders deviate from their essence of "technical verification and industrial pavement" and become tools for companies to dress up their performance and inflate valuations, systemic harm to the entire industry may emerge.

In the new energy vehicle industry, some companies focused on "building cars for subsidies," investing funds in expanding production capacity rather than core technological R&D. Ultimately, after the subsidy period ended, they faded away due to technological backwardness and lack of market competitiveness.

Today, similar signs are emerging in the robot industry. Some companies are more concerned with inflating revenue and valuations through related transactions while underinvesting in core component R&D and self-sustaining capability building. There is even a tendency to "prioritize order quantity over technological breakthroughs," which runs counter to the industry's need for long-term technological accumulation.

More alarmingly, if related orders become the industry norm, a "bad money drives out good" competitive environment may form. Companies focused on market-driven orders and high R&D investment may see relatively slow revenue growth and valuations far lower than those relying on related orders. This could lead capital to flow toward companies "good at securing orders" rather than "good at developing technologies," ultimately delaying the entire industry's technological breakthrough pace.

We must beware of the industry falling into the misconception (misconception) of "prioritizing appearance over substance" and recognize that a company's core value and advantages extend far beyond a few favorable related order announcements.

Of course, the dangers of false prosperity manifest in multiple layers: financially, over-reliance on related orders may lead to "inflated" revenue and even hide fraud risks. If related parties have insufficient payment capabilities, companies may face cash flow pressures. Technologically, easily obtained related orders may weaken a company's innovation drive, leading to stalled technological iterations, as "easy meals" do not foster self-reliance. Market judgment-wise, false order data may mislead the industry's perception of demand, trapping companies in "order inertia" and losing their ability to explore real markets.

The "left hand to right hand" order phenomenon in the robot industry is not a simple dichotomy of "good versus bad." Instead, it is a complex outcome shaped by specific stages of industrial development. Drawing parallels from the new energy vehicle industry, such orders play an irreplaceable "stage value" role in technical validation and capacity expansion. However, as the industry transitions into large-scale commercialization, it must ultimately pivot back to the core of "real demand."