HKUST and Others Propose a New Paradigm for Audio-Driven Multi-Person Video Generation: AnyTalker, Unlocking Natural Interactions Among Any Number of Characters!

![]() 12/04 2025

12/04 2025

![]() 614

614

Interpretation: The Future of AI Generation

Highlights

Scalable Multi-Person Driving Structure: This paper proposes a scalable multi-stream processing structure, the Audio-Face Cross Attention Layer, capable of driving any number of characters in a cyclical manner while ensuring natural interactions among them.

Low-Cost Multi-Person Speaking Pattern Training Method: A novel two-stage training process is introduced, enabling the model to first learn multi-person speaking patterns using horizontally concatenated single-person data, followed by fine-tuning with multi-person data to optimize interactions among generated video characters.

First Interactivity Evaluation Metric: A new metric for quantifying and evaluating multi-character interactivity is proposed for the first time, along with a benchmark dataset for systematic assessment.

Summary Overview

Problems Addressed

Scalability: Some methods assign fixed tokens or routing orders to characters in the same video during training, making it difficult to break the 'duo' limit and generate naturally interacting videos with more than two identities.

High Training Costs: Existing methods generally rely on costly multi-person scene datasets for training. Multi-person scenes involve complex non-verbal factors such as turn-taking, role changes, and eye contact, leading to high data collection and annotation costs.

Lack of Quantitative Interactivity Evaluation: As a relatively new field, metrics previously used for single-person lip-syncing or video quality are insufficient to fully measure the naturalness of interactions among multiple characters in multi-person scenes.

Proposed Solutions/Applied Technologies:

Building a Scalable Multi-Stream Processing Structure: Cross-attention modules tailored for each audio-identity pair. Facial clip image features and Wav2Vec2 audio features are concatenated along the sequence dimension, serving as K/V together. The computed attention results are locally activated according to the unfolded face mask token of the sequence, modifying only the corresponding facial region. This operation can be performed cyclically for each 'character-audio' pair to support any number of participants.

Proposing a Low-Cost Multi-Person Dialogue Learning Strategy: During the first-stage training, only single-person data is used, with a 50% probability of horizontally concatenating two single-person videos into 'dual-dialogue' pseudo-samples. This fully utilizes vast amounts of single-person data, allowing the model to quickly learn multi-person speaking patterns. In the second stage, a small amount of real multi-person data is used to optimize interactivity.

Pioneering an Interactivity Quantification Metric: Tracking the displacement amplitude of the listener's eye keypoints during silent periods measures the interactivity strength of the generated video, enabling objective assessment of multi-person interaction effects.

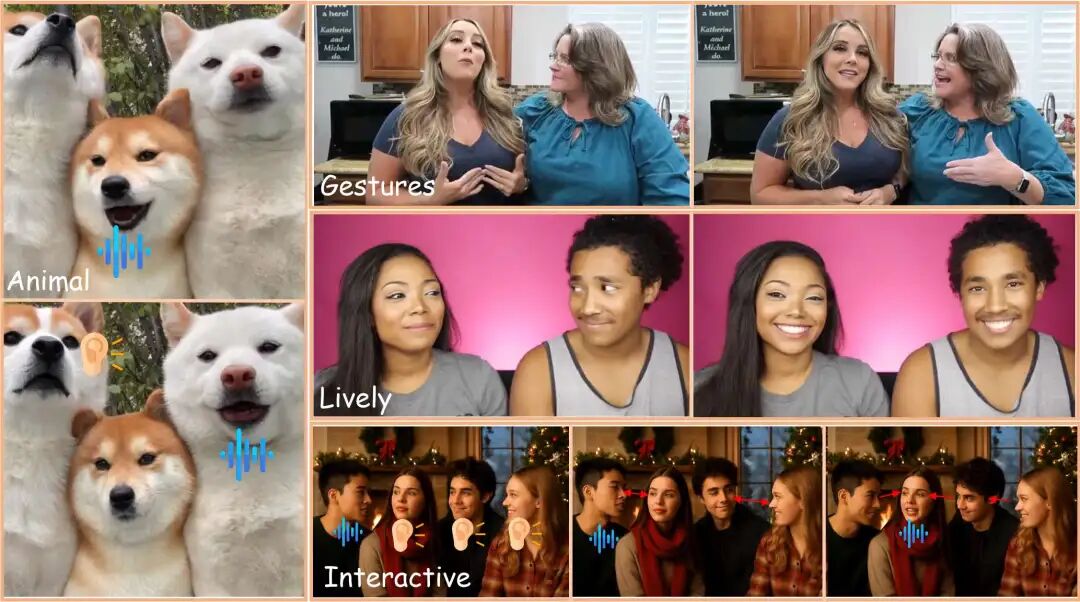

Figure 1: AnyTalker is a powerful audio-driven multi-person video generation framework capable of producing videos rich in gestures, vivid emotions, and interactivity, freely extendable to any number of IDs or even non-real inputs.

Achieved Effects:

Breaking the Limit of Drivable Persons: Whether the input is a single monologue or a multi-person dialogue, AnyTalker can adaptively match the audio with the number of characters, generating natural and fluent multi-person speaking videos with a single click.

Authentic and Nuanced Interactions: In the generated videos, characters naturally engage in non-verbal actions such as eye contact, eyebrow raises, and nods. Facial expressions precisely respond to speech rhythms, presenting highly realistic multi-person interaction scenes and far outperforming all previous methods on the newly proposed interactivity benchmark.

Accurate Lip-Syncing: On the HDTF and VFHQ single-speaker video benchmarks, AnyTalker leads in the Sync-C metric; it also maintains an advantage on the newly constructed multi-person dataset in this paper.

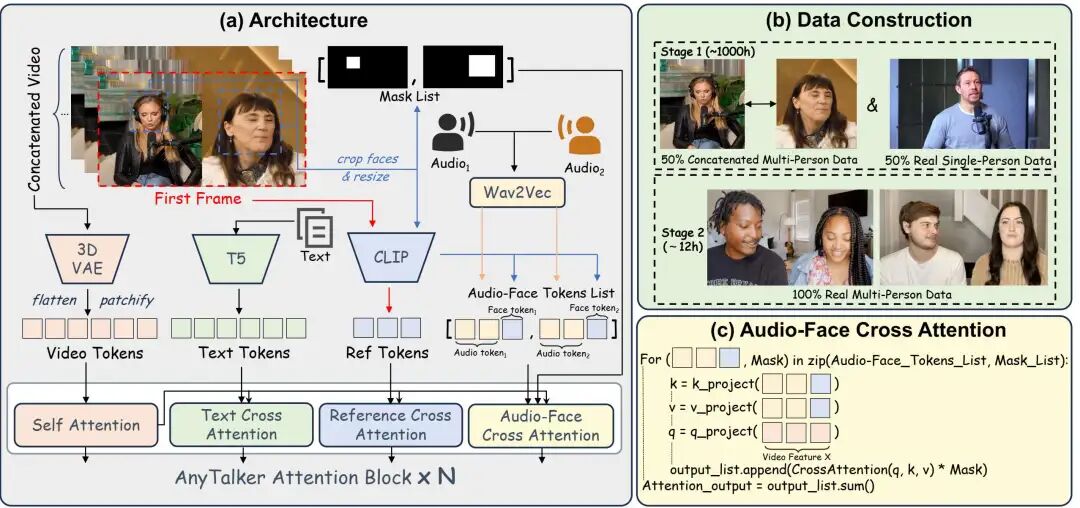

Methods  Figure 2: (a) AnyTalker's architecture adopts a novel multi-stream audio processing layer, the Audio-Face Cross Attention Layer, capable of handling multiple facial and audio inputs. (b) AnyTalker's training is divided into two stages: the first stage uses single-person data and its mixed cascaded multi-person data to learn lip movements; the second stage employs real multi-person data to enhance interactivity in the generated videos. (c) Detailed implementation of audio-face cross attention, a cyclically callable structure that applies masks to outputs using face masks.

Figure 2: (a) AnyTalker's architecture adopts a novel multi-stream audio processing layer, the Audio-Face Cross Attention Layer, capable of handling multiple facial and audio inputs. (b) AnyTalker's training is divided into two stages: the first stage uses single-person data and its mixed cascaded multi-person data to learn lip movements; the second stage employs real multi-person data to enhance interactivity in the generated videos. (c) Detailed implementation of audio-face cross attention, a cyclically callable structure that applies masks to outputs using face masks.

Overview

The overall AnyTalker framework proposed in this paper is shown above. AnyTalker inherits some architectural components from the Wan I2V model. To handle multiple audio and identity inputs, a specialized multi-stream processing structure called Audio-Face Cross Attention (AFCA) is introduced, and the overall training process is divided into two stages.

As a DiT-based model, AnyTalker converts 3D VAE features into tokens through patchify and flatten operations, while text features are generated by a T5 encoder. Additionally, AnyTalker inherits the Reference Attention Layer, a cross-attention mechanism that utilizes a CLIP image encoder to extract features from the first frame of the video. Wav2Vec2 is also employed to extract audio features. The overall input features can be represented as:

Audio-Face Cross Attention

To enable multi-person dialogues, the model must handle multiple audio inputs. Potential solutions may include the L-RoPE technique used in MultiTalk, which assigns unique labels and biases to different audio features. However, the range of these labels needs to be explicitly defined, limiting their scalability. Therefore, we designed a more scalable structure to drive multiple identities in an extensible manner and achieve precise control.

As shown in Figures 2(a) and (c), we introduce a dedicated structure called Audio-Face Cross Attention (AFCA), which can be executed cyclically multiple times based on the number of input face-audio pairs. As shown in Figure 2(c) and Equation (4), it can flexibly handle multiple different audio and identity inputs, with the outputs of each iteration summed to obtain the final attention output.

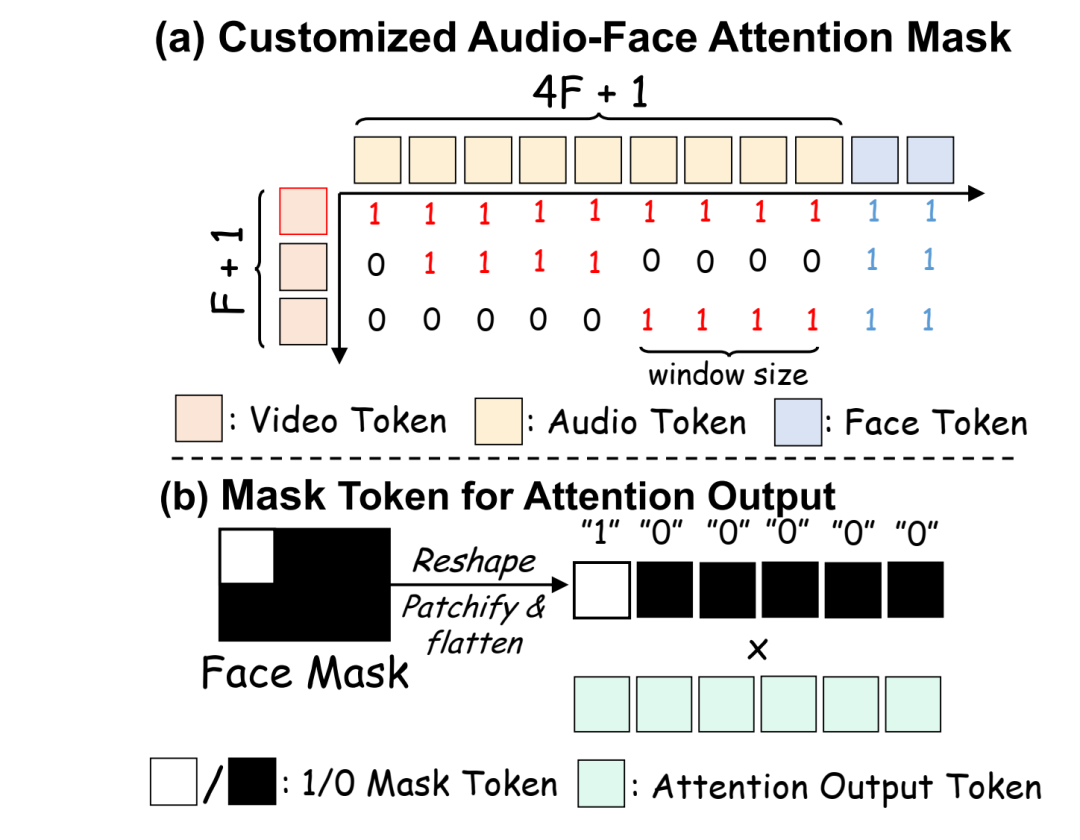

Figure 3: (a) Suggesting mappings from video tokens to audio tokens through customized attention masks. Every 4 audio tokens are bound to 1 video token, except for the first token. (b) Tokens used for output masking in Audio-Face Cross Attention.

Figure 3: (a) Suggesting mappings from video tokens to audio tokens through customized attention masks. Every 4 audio tokens are bound to 1 video token, except for the first token. (b) Tokens used for output masking in Audio-Face Cross Attention.

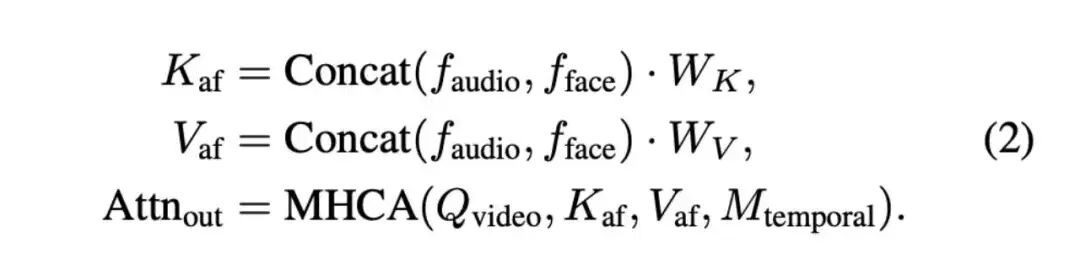

Audio Token Modeling. We use Wav2Vec2 to encode audio features. The first latent frame attends to all audio tokens, while each subsequent latent frame only attends to a local time window corresponding to four audio tokens. Structured alignment between video and audio streams is achieved by applying temporal attention masks, as shown in Figure 3(a). Additionally, for comprehensive information integration, each audio token is concatenated with the face token encoded by during AFCA computation. This concatenation enables all video query tokens to effectively attend to different audio and face information pairs, calculated as follows:

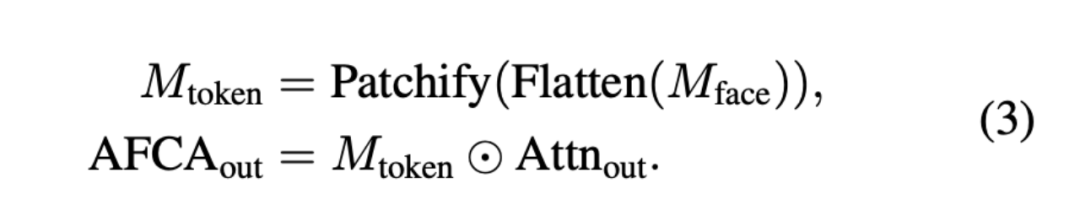

Where MHCA denotes multi-head cross-attention, and W_K and W_V represent the key and value matrices, respectively. The attention output Attn_out is subsequently adjusted by the face mask token, as described in Equation (3).

Face Token Modeling. Face images are obtained by online cropping the first frame of selected video clips during training using InsightFace, while face masks are precomputed to cover the maximum facial region across the entire video, i.e., the global face bounding box. This mask ensures that facial actions do not exceed this region, preventing erroneous activation of video tokens after reshaping and flattening operations, especially for videos with significant facial displacement. This mask, having the same dimensions as , can be directly used for element-wise multiplication to compute the Audio-Face Cross Attention output, as follows:

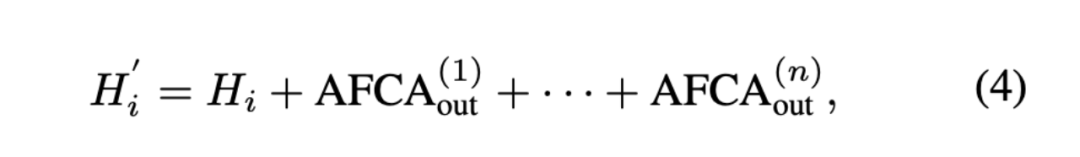

Thus, the hidden state of each I2V DiT block can be represented as:

Where i denotes the layer index of the attention layer, and n represents the number of identities. Note that all terms are generated by the same AFCA layer with shared parameters. AFCA computation is iteratively applied n times, once for each character, allowing the architecture to scale arbitrarily to the number of drivable identities.

Training Strategy

AnyTalker explores the potential of leveraging single-person data to learn multi-person speaking patterns, where low-cost single-person data constitutes the majority of the training data.

Single-Person Data Pretraining. We train the model using standard single-person data and synthetic dual-person data generated through horizontal concatenation. Each batch of data is randomly configured as dual-person or single-person mode with a 50% probability, as shown in Figure 2(b). In dual-person mode, each sample in the batch is horizontally concatenated with the data of its next index and corresponding audio. This approach maintains consistent batch sizes between the two modes. Additionally, we predefined some generic text prompts to describe dual-person dialogue scenarios.

Multi-Person Data Interactivity Optimization. In the second stage, we fine-tune the model using a small amount of real multi-person data to enhance interactivity among different identities. Although our training data only contains interactions between two identities, we surprisingly found that the model equipped with the AFCA module can naturally generalize to scenarios with more than two identities, as shown in Figure 1. We speculate that this is because the AFCA mechanism enables the model to learn universal patterns of human interaction, including not only accurate lip-syncing to audio but also listening and responding to the speaking behaviors of other identities.

To construct high-quality multi-person training data, we established a rigorous quality control process, using InsightFace to ensure the presence of two faces in most frames, audio separation to isolate audio and ensure only one or two speakers, optical flow to filter excessive motion, and Sync-C scores to pair audio with faces. This process ultimately produced a total of 12 hours of high-quality dual-person data, a relatively small amount compared to previous methods. Since AnyTalker's AFCA design inherently supports multi-identity inputs, the dual-person data is input to the model in the same format as the concatenated data from the first stage, without requiring additional processing.

In summary, the single-person data training process enhances the model's lip-syncing ability and generation quality while also learning multi-person speaking patterns. Subsequently, lightweight multi-person data fine-tuning compensates for the real interactions among multiple persons that single-person data cannot fully cover.

Interactivity Evaluation

However, existing evaluation benchmarks for single-person talking head generation are insufficient to assess natural interactions among characters. Although InterActHuman introduced a related benchmark, its test set is limited to single-speaker scenarios, unfavorable to (unfavorable for) assessing interactions among multiple characters. To fill this gap, we meticulously constructed a set of videos featuring two different speakers for evaluating interactivity.

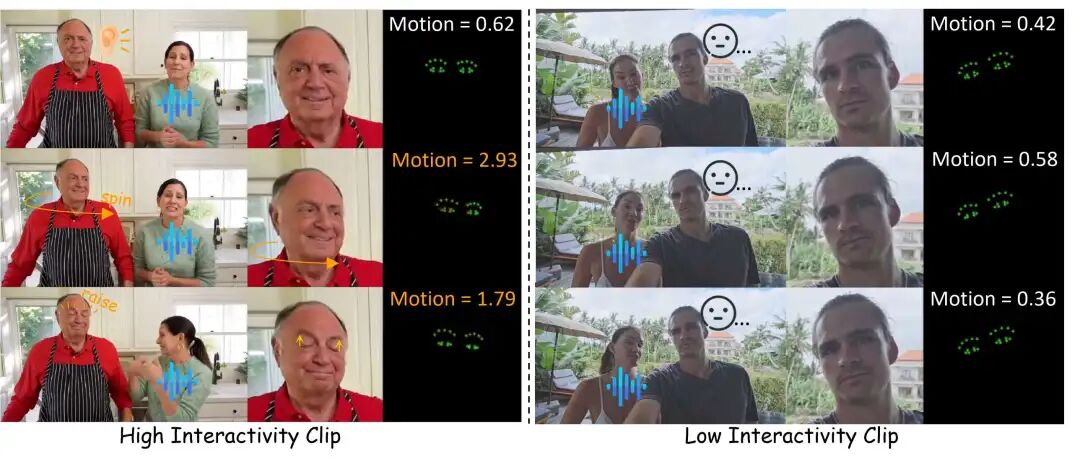

Figure 4: Two video clips from InteractiveEyes, with motion scores (in pixels): the left shows the original video, while the right displays the cropped face and eye keypoints. Turning the head toward the speaker or raising eyebrows increases motion and interactivity; sustained stillness keeps both scores low.

Figure 4: Two video clips from InteractiveEyes, with motion scores (in pixels): the left shows the original video, while the right displays the cropped face and eye keypoints. Turning the head toward the speaker or raising eyebrows increases motion and interactivity; sustained stillness keeps both scores low.

Dataset Construction

We selected interactive dual-person videos to construct the video dataset, named InteractiveEyes. Figure 4 showcases two clips from it. Each video is approximately 10 seconds long, consistently featuring two characters throughout the entire clip. Additionally, through meticulous manual processing, we segmented the audio of each video to ensure that most videos encompass both speaking and listening scenarios for the two persons, as shown in Figure 5. We also ensured that each video contains instances of mutual gaze and head movements to provide authentic references.

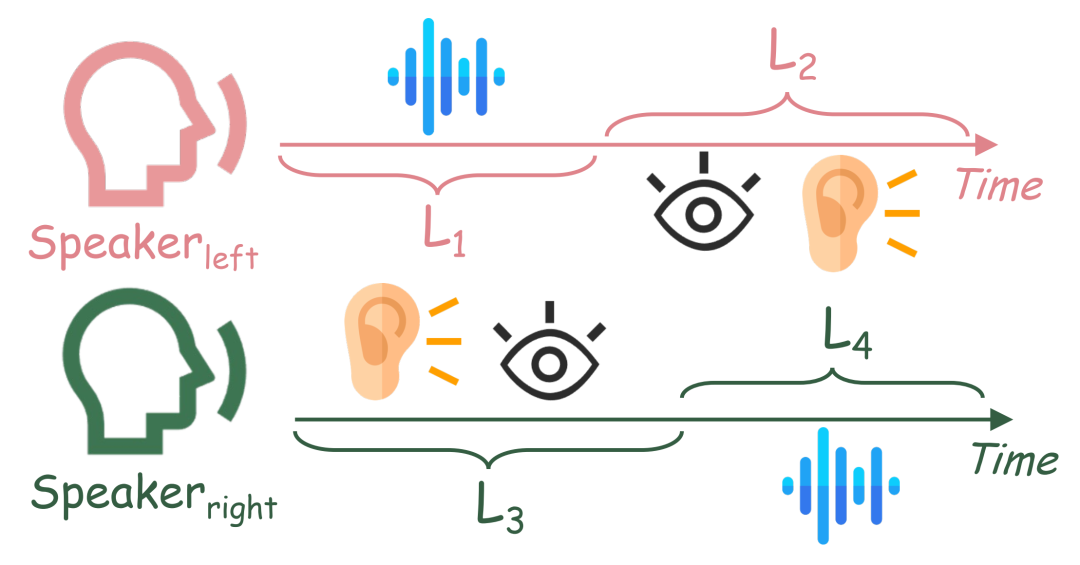

Figure 5: Listening and speaking time periods for each role

Figure 5: Listening and speaking time periods for each role

Proposed Interactivity Metrics

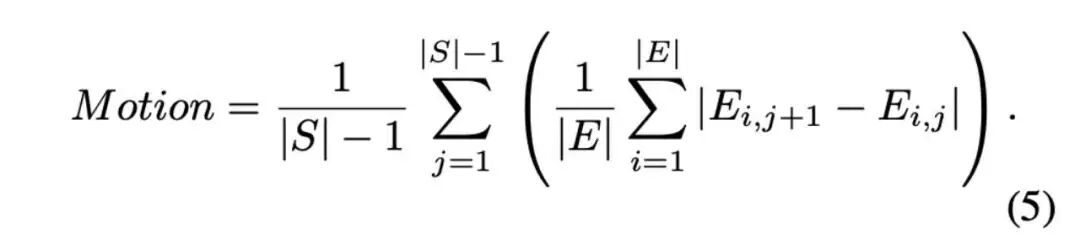

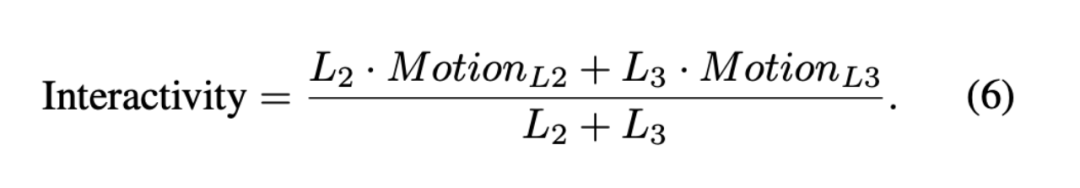

In addition to the dataset, we introduce a new metric, eye-focused Interactivity, to evaluate natural interaction between speakers and listeners. Since eye contact is a fundamental and spontaneous behavior in conversational contexts, we use it as a key reference for interactivity. Inspired by the Hand Keypoint Variance (HKV) metric used in CyberHost, we propose a quantitative method for evaluating interactivity by tracking the magnitude of eye keypoint movements. To this end, we extract a sequence of face-aligned eye keypoints in generated frames, where S represents the frame sequence and E represents the eye keypoints. Motion is calculated as follows:

Here, i and j denote the eye keypoint index and frame index, respectively, and ,j represents the eye keypoints in each frame. This formula intuitively calculates the displacement and rotation of the eye region. We then calculate motion during the listening period. The reason is that most generation methods perform well when activating the speaker, but listeners often appear stiff. Therefore, evaluation during listening is more targeted and valuable. The length of each person's speaking and listening periods is shown in Figure 5, denoted as . To quantify the listener's responsiveness, we calculate the average motion intensity during the listening phases and :

This metric effectively measures interactivity in generated multi-role videos. As shown in Figure 4, the proposed metric aligns well with human perception: static or slow eye movements receive lower motion scores, while head turns and eyebrow raises increase scores, indicating higher interactivity.

Experiments

Dataset. We expanded a commonly used single-person training dataset and incorporated network-collected data, totaling approximately 1,000 hours for the first-stage training. For the second-stage training, we collected two-person dialogue clips and retained only about 12 hours after filtering. Evaluation was conducted on two benchmarks: (i) the standard talking head benchmarks HDTF and VFHQ, and (ii) our self-collected multi-person dialogue dataset (including head and body movements, with both roles speaking). We randomly selected 20 videos from each benchmark, ensuring their identities did not appear in the training set.

Implementation Details. To comprehensively evaluate our method, we trained two models of different scales: Wan2.1-1.3B-Inp and Wan2.1-I2V-14B, serving as the base video diffusion models for our experiments. In all stages, the text, audio, and image encoders, as well as the 3D VAE, remained frozen. All parameters of the DiT main network (including the newly added AFCA layers) were open for training. The first stage was pre-trained with a learning rate of 2×10−5; the second stage was fine-tuned with a learning rate of 5×10−6, using the AdamW optimizer, and trained on 32 NVIDIA H200 GPUs.

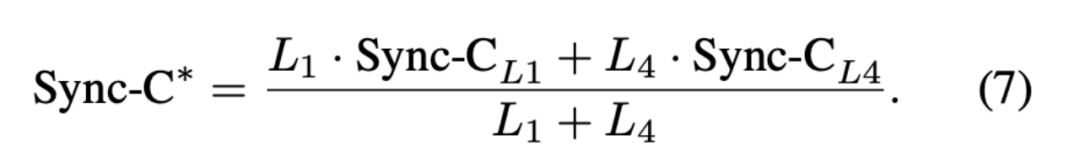

Evaluation Metrics. For the single-person benchmark, we adopted various commonly used metrics: Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) and Fréchet Video Distance (FVD) to assess the quality of generated data, Sync-C to measure audio-lip synchronization, and identity similarity between the first frame and the remaining frames. For the multi-person benchmark, we evaluated from different dimensions. The newly introduced metric, Interactivity, served as the primary evaluation metric. For the FVD metric, the calculation method was similar to that of the single-person benchmark. For the Sync-C metric, we refined it to Sync-C*, focusing only on lip synchronization during each role's speaking period, thereby avoiding the impact of long listening passages on the final lip synchronization score. The specific formula is:

Here, and represent the speaking time periods shown in Figure 5.

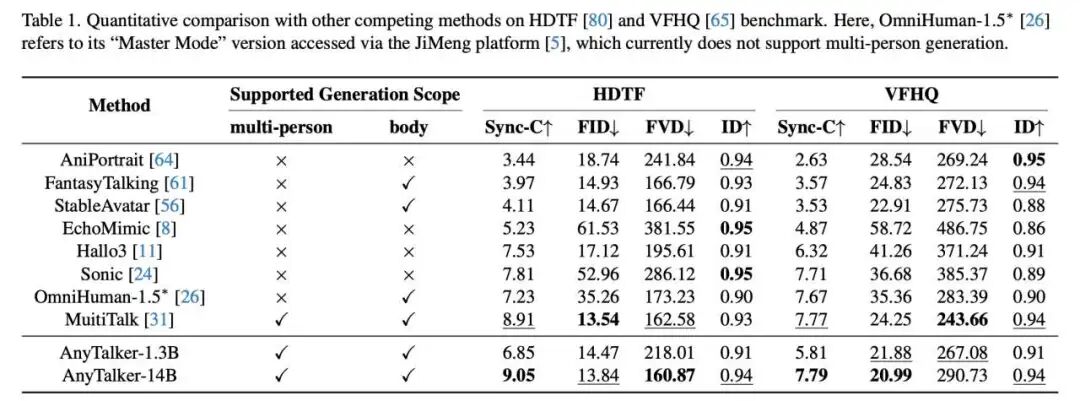

Comparison Methods. We compared our approach with several state-of-the-art talking video generation methods. For single-person generation, we compared with AniPortrait, EchoMimic, Hallo3, Sonic, FantasyTalking, StableAvatar, OmniHuman-1.5, and MultiTalk. For multi-person generation, we selected Bind-Your-Avatar and MultiTalk for quantitative and qualitative comparisons.

Comparison with SOTA Methods

Quantitative Comparison. First, we compared with several single-person generation methods to verify its outstanding single-person driving capability. The quantitative results are shown in Table 1. Although AnyTalker was not specifically designed for driving talking faces, it achieved the best or competitive results across all metrics. Additionally, AnyTalker's 1.3B model significantly outperformed AniPortrait, EchoMimic, and StableAvatar in lip synchronization, despite having a similar number of parameters. These results demonstrate the excellent and comprehensive driving capability of the AnyTalker framework.

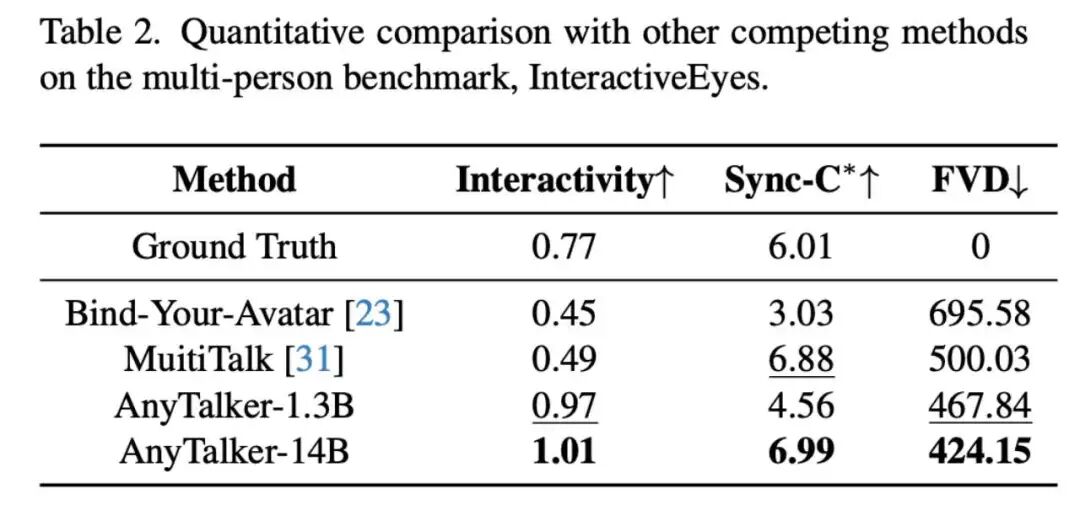

Subsequently, we used the multi-person dataset InteractiveEyes and related metrics to evaluate AnyTalker's ability to maintain accurate lip synchronization and natural interactivity when driving multiple identities. In this comparison, we contrasted AnyTalker with the existing open-source multi-person driving methods MultiTalk and Bind-Your-Avatar. The results in Table 2 show that AnyTalker's 1.3B and 14B models achieved the best performance on the Interactivity metric. Furthermore, the 14B model achieved the best results across all metrics, validating the effectiveness of our proposed training pipeline. We also demonstrated AnyTalker's ability to generate interaction-rich videos through quantitative evaluation.

Qualitative Comparison. We selected a real human input from the InteractiveEyes dataset and used an input generated by an AIGC model, both accompanied by corresponding text prompts and dual audio streams, for quantitative evaluation and comparison using Bind-Your-Avatar, MultiTalk, and AnyTalker. As shown in Figure 6, AnyTalker generated more natural videos compared to other methods, featuring eye and head interactions. MultiTalk exhibited weaker eye interactions, while Bind-Your-Avatar often produced stiffer expressions. This trend further validates the effectiveness of our proposed Interactivity metric. AnyTalker not only generates natural two-person interactive talking scenes but also scales well to multiple identities, as shown in Figure 1, effectively handling interactions among four identities.

Figure 6: Qualitative comparison of various multi-person driving methods. Using the same text prompts, reference images, and multiple audio streams as inputs, we compared the generation results of Bind-Your-Avatar, MultiTalk, and AnyTalker. The left case uses an input image from the InteractiveEyes dataset, while the right case uses an image generated by a text-to-image model as input.

Figure 6: Qualitative comparison of various multi-person driving methods. Using the same text prompts, reference images, and multiple audio streams as inputs, we compared the generation results of Bind-Your-Avatar, MultiTalk, and AnyTalker. The left case uses an input image from the InteractiveEyes dataset, while the right case uses an image generated by a text-to-image model as input. Figure 7: More video results generated by AnyTalker

Figure 7: More video results generated by AnyTalker

Conclusion

In this paper, we introduced AnyTalker, an audio-driven framework for generating multi-person talking videos. It proposes a scalable multi-stream processing structure called Audio-Face Cross Attention, enabling identity expansion while ensuring seamless cross-identity interaction. We further propose a generalizable training strategy that maximizes the use of single-person data through concatenation-based augmentation to learn multi-person talking patterns. Additionally, we introduced the first interactivity evaluation metric and a dedicated dataset for comprehensive interactivity assessment. Extensive experiments demonstrate that AnyTalker achieves a good balance among lip synchronization, identity scalability, and interactivity.

References

[1] AnyTalker: Scaling Multi-Person Talking Video Generation with Interactivity Refinement