How Does BEV Empower Autonomous Vehicles to "See" Further?

![]() 01/26 2026

01/26 2026

![]() 541

541

In the realm of autonomous driving, discussions centered around BEV-related technologies are a common occurrence. BEV stands for Bird’s Eye View, which is translated into Chinese as “bird’s-eye perspective” or “top-down view”. In essence, it entails mapping information gathered from cameras, LiDAR, millimeter-wave radar, or maps onto a single plane, with the vehicle at its center or based on world coordinates. The autonomous driving system then “sees” from an aerial vantage point, simultaneously perceiving the positions of all surrounding objects, lane markings, and the distribution of both static obstacles and dynamic traffic participants. BEV effectively transforms 3D perception challenges into 2D spatial reasoning tasks, streamlining the integration of perception, prediction, and planning, and thereby bolstering the safety of autonomous driving.

As an intermediate representation, BEV places a strong emphasis on spatial consistency. Regardless of the sensor type or temporal variations, information can ultimately be represented on the same plane and coordinate system. For autonomous driving systems, the intuitive benefits of a unified perspective are readily apparent: the planner can directly pinpoint traversable areas on a map-like plane, the prediction module can estimate trajectories based on a unified coordinate system, and the outputs of the perception module are more easily processed by subsequent modules, facilitating a smoother end-to-end workflow.

Technical Architecture and Key Implementation Aspects of BEV

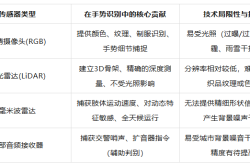

Converting sensor data into a usable BEV representation involves a series of technical steps, including sensor encoding, perspective transformation and alignment, feature fusion and BEV encoding, temporal processing, and task heads (such as detection, semantic segmentation, trajectory prediction, and occupancy grid output). These steps vary depending on the sensor combination (pure vision, vision + radar, vision + LiDAR), but the overall approach remains consistent.

In a setup utilizing only cameras, images from each camera are initially processed through a feature extraction network (such as convolutional neural networks or vision transformers) to obtain high-dimensional feature maps. These perspective features are then “projected” onto a top-down plane. The simplest projection method for pure camera BEV relies on geometric transformations, such as employing camera intrinsics/extrinsics and a depth estimation module to back-project pixels into 3D points, which are subsequently projected onto the plane according to ground coordinates to form a BEV feature projection map. Some technical solutions incorporate learnable modules in the pixel-to-BEV mapping, enabling these modules to learn during training how to aggregate features from different perspectives and scales into the BEV grid in the most appropriate manner, thereby mitigating gaps or errors caused by direct geometric projection.

In systems equipped with LiDAR, BEV is achieved by projecting the LiDAR point cloud onto a BEV grid (commonly referred to as a bird’s-eye raster) and encoding information such as point cloud intensity, point count, and maximum/minimum height into the features of each grid cell. The precise depth information provided by LiDAR enhances the positioning accuracy of the BEV representation and makes occupancy estimation more reliable.

Millimeter-wave radar offers sparse yet valuable velocity information, supplementing dynamic information in BEV. Radar echoes can be projected onto the BEV grid for velocity field estimation or as auxiliary features. The crux of BEV implementation lies in the accuracy of coordinate transformations, temporal alignment across multiple sensors, and efficient representation of semantic and motion information on the BEV grid.

Common components within the BEV network architecture encompass the BEV encoder (which performs further convolution/transformation on the BEV grid to expand the receptive field and enhance semantic aggregation), a cross-time fusion module (which fuses BEV features from multiple time steps to glean motion cues), and several task heads (for outputting detection boxes, segmentation masks, occupancy probabilities, trajectory predictions, etc.). Temporally, ego-motion compensation must be taken into account, meaning BEV features from previous frames must be inversely transformed into the current coordinate system before fusing information from different time steps to prevent misalignment due to vehicle motion.

Impact and Advantages of BEV on Autonomous Driving Systems

As a “space-oriented” representation, BEV enables the planner to search for traversable areas, avoid obstacles, and generate trajectories on a single map. Compared to processing multiple perception boxes or raw outputs from different camera perspectives, utilizing BEV provides the planning module with semantic, occupancy-probability-annotated map-like data with precise coordinates, rendering the design more intuitive and less intertwined.

BEV also simplifies multi-sensor fusion. Cameras excel at semantic recognition (such as pedestrians, lane markings, traffic signs), LiDAR provides accurate geometry and distance information, and millimeter-wave radar is adept at velocity measurement. By projecting all this information onto the same BEV grid, fusion methods transition from “complex feature alignment across sensors” to “channel or attention fusion in a unified space,” ensuring better consistency and reducing information loss. This unified representation also streamlines the alignment of maps (including high-definition or vector maps) with real-time perception for correcting perception results or constraining planning outputs.

BEV is advantageous for advancing end-to-end or large-model approaches. Networks trained on BEV can simultaneously output multiple tasks such as detection, segmentation, and trajectory prediction, sharing the same spatial representation. This enhances multi-task learning effectiveness and enables more efficient parameter sharing. For research routes aiming to jointly optimize decision-making and control closer to the perception end, BEV provides a natural intermediate interface, making joint training from “perception to trajectory” feasible.

BEV enhances the capacity to handle complex traffic scenarios. Complex intersections, multi-lane merges, roundabouts, and predictions of multi-modal behaviors necessitate long-term spatial and dynamic reasoning. BEV conveniently displays spatial interactions; for instance, even if a vehicle is obscured by another, its approximate position can be inferred from trajectory history and velocity fields on BEV, providing more contextual information for the prediction module.

BEV also facilitates system debugging and visualization. Engineers can directly view BEV images during development or playback to ascertain whether recognition errors stem from depth estimation errors, projection errors, or sensor calibration issues. This visual intuition significantly accelerates the development and problem-solving processes.

Limitations, Challenges, and Future Development Directions

One of the most significant challenges for pure vision-based BEV is depth and scale uncertainty. Monocular cameras lack precise depth information, and projecting pixel features onto a plane necessitates reliable depth estimation or assumptions about the ground plane, which are prone to errors in scenes with ramps, bridges, or complex 3D traffic structures. To address this, dense depth estimation, structured light, or LiDAR assistance may be employed, or learnable view transformation modules can be integrated into the network to reduce geometric errors.

Another challenge for BEV is striking a balance between resolution and computational resources. Encoding the surrounding environment with high-resolution grids increases memory and computational pressure, while low resolution compromises the ability to recognize small objects (such as pedestrians, child cyclists). Design choices must strike a balance between BEV grid size, feature channel count, and the number of time steps, while also considering the impact of real-time performance and latency on control safety.

Temporal and spatial alignment across multiple sensors is another major hurdle in BEV applications. Camera frame rates, LiDAR point cloud rates, and radar echo rates vary, and each sensor has its own latency and jitter. Accurately synchronizing, compensating, and mapping them onto the same BEV grid requires precise timestamps, extrinsics, and robust motion compensation mechanisms. Even minor errors in any step can accumulate into significant positional offsets on BEV, affecting downstream planning.

Training a robust BEV model places extremely stringent demands on data annotation and training samples. Not only is massive multi-sensor data coordination over long time scales required, but labels must also align precisely with the grid in BEV space. The cost of such annotation is prohibitively high, and to ensure model generalization, diverse long-tail scenarios such as nighttime, rain, snow, and tunnels must be covered, leading to pronounced data distribution bias. To address these challenges, simulator-based data generation and weakly/self-supervised learning have emerged as important supplementary approaches. However, seamlessly transferring training results from simulated environments to real-world scenarios remains a critical unsolved problem.

Final Thoughts

BEV is a highly practical and widely adopted spatial representation in the current perception and decision-making pipeline of autonomous driving. By unifying multi-modal and multi-temporal information under a single planar perspective, it renders reasoning about complex traffic scenarios more manageable and intuitive.

-- END --