Can Autonomous Vehicles Interpret Traffic Police Hand Gestures?

![]() 01/26 2026

01/26 2026

![]() 568

568

In the intricate web of urban traffic systems, driving regulations are far from static. While traffic signals, road markings, and various signs lay the groundwork for road operations, traffic police step in to manage traffic flow in special situations, such as during traffic accident management, power outages leading to signal failures, and extreme traffic congestion. For human drivers, recognizing and responding to the hand gestures of traffic police is a natural instinct. However, for autonomous driving systems, this task requires a sophisticated integration of perception, understanding, and decision-making technologies.

How Do Autonomous Vehicles Interpret Human Body Language?

The first step for autonomous vehicles in recognizing traffic police gestures is through meticulous environmental perception. Early computer vision solutions primarily relied on rigid 'bounding boxes' to locate objects. While this method could isolate traffic police from complex backgrounds and identify them as 'humans,' it fell short in capturing critical command information. To overcome this, autonomous driving systems introduced human pose estimation technology. Instead of viewing traffic police as a whole, this technology constructs a detailed biomechanical skeleton model by identifying key points across the body, such as shoulders, elbows, wrists, hips, and ankles.

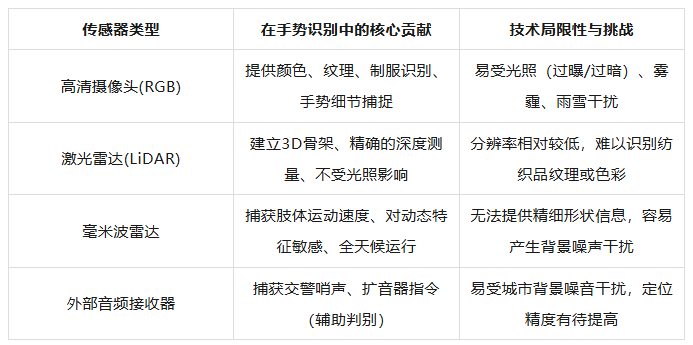

To achieve this, multiple sensors on the vehicle must work in tandem. Cameras, as the visual core, capture color and texture information, enabling the system to identify the uniform features of traffic police, the styles of reflective vests, and subtle hand movements. However, cameras can suffer from perception degradation under strong direct light, nighttime conditions, or rainy/snowy weather. In such scenarios, LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) emits laser pulses and receives reflected point clouds, providing the system with a precise three-dimensional model of the world, complete with depth information. Even in dim lighting, LiDAR can outline the spatial trajectory of the traffic police's arm movements. Millimeter-wave radar, on the other hand, can monitor Doppler frequency changes in the traffic police's body movements in real-time, perceiving the intensity and rhythm of their actions. This multimodal data fusion enables the autonomous driving system to create a digital vision that surpasses human eyesight and operates effectively in all weather conditions.

To enhance recognition reliability, the autonomous driving system must verify the identity of the traffic police. In a traffic environment, not all waving actions carry command significance. Gestures from pedestrians hailing a ride, construction workers, or ordinary passersby are irrelevant to autonomous vehicles. Therefore, the perception layer must finely classify targets using convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to confirm whether they are wearing specific uniforms or holding command batons.

Once the system identifies the traffic police, subsequent computational resources are focused on tracking the target's pose changes. Current algorithms like MoveNet or MediaPipe can extract key human body points with minimal computational latency, which is crucial for making instantaneous judgments while traveling at high speeds.

When processing complex hand movements, challenges such as glove color, hand occlusion by other body parts, or the traffic police facing sideways toward the vehicle arise. To enhance robustness, some technologies propose three-dimensional hand models. Through deep learning of key frames, the autonomous driving system can infer the possible poses of occluded parts. For instance, Waymo's perception system can simultaneously track the dynamics of hundreds of pedestrians at busy intersections and filter out command signals that directly affect vehicle movement. This hierarchical recognition architecture, moving from whole to part, forms the first technological barrier for autonomous driving systems to interpret human commands.

Time Series Modeling and Dynamic Interpretation of Gesture Semantics

For autonomous vehicles, merely capturing an instantaneous pose does not equate to understanding instructions, as traffic commanding involves a continuous sequence of actions. A complete 'stop' instruction may include raising an arm, palm facing outward, and maintaining a certain rigidity; whereas a 'turn left' instruction involves a series of trajectories, including pointing at the vehicle, sweeping across the chest, and pointing sideways. Therefore, gesture recognition is essentially a process of video classification and action understanding, requiring the autonomous driving system to process 'temporal correlations.'

To achieve this temporal memory, autonomous driving systems can employ recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and their improved architectures, such as Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTMs) and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs). These network structures retain information states from previous moments while processing each frame of an image. This 'memory' mechanism allows the model to connect the motion directions of arms across dozens of past frames, thereby identifying the semantics of actions. For example, when the system observes the traffic police's arm moving smoothly from a low to a high position, it interprets it not simply as a 'displacement' but as a prelude to the 'start moving' gesture.

To enhance the accuracy of command gesture judgment, a mechanism called the 'flag bit sequence algorithm' can be utilized. This mechanism simultaneously monitors the traffic police's body orientation, gaze focus, and arm trajectory. When the traffic police's gaze is fixed on the vehicle, and their arm makes a targeted guiding action, the autonomous driving system marks the sequence as a 'valid instruction.' This logic effectively filters out invalid actions, such as when the traffic police are directing side traffic or organizing equipment.

To further reduce system latency, some technologies propose a 'skeleton-free' gesture recognition approach. Instead of expending computational resources to precisely locate each finger joint, this method directly identifies the overall pointing vector of the arm using a trained lightweight detector and maps it to a predefined set of instructions. This approach maintains an accuracy rate of over 91% while significantly increasing the frames processed per second (FPS), enabling the vehicle to interpret the latest intentions of traffic police in real-time during high-speed movement. This transition from 'fine modeling' to 'semantic mapping' also reflects the balance between efficiency and precision in autonomous driving.

Data quality is paramount for training these complex models. Companies like Waymo leverage their vast road test databases to extract millions of real-world clips containing traffic police commands through 'content search' technology. These data are used to train multi-layered deep neural networks, enabling them to understand subtle differences in commanding habits across different countries and cultural backgrounds.

End-to-End Architecture and Physical World Understanding Powered by Large Models

As artificial intelligence enters the era of large models, the technological approach for autonomous driving systems to recognize traffic police gestures is undergoing a transformation. Traditional perception systems are modular, with visual algorithms outputting coordinates, logical algorithms outputting semantics, and planning algorithms outputting instructions. Although this chained structure is clear, it can appear rigid when dealing with highly abstract and uncertain human behaviors due to information loss between layers. In contrast, large models like VLA (Vision-Language-Action) attempt to integrate these layers, constructing an 'end-to-end' direct mapping capability.

In this new architecture, traffic police gestures are no longer simplified to 'stop' or 'go' labels. Instead, the system transforms the captured video stream into implicit 'physical markers,' which are directly input into a large model with billions of parameters. This model has not only learned how to drive but also understands extensive traffic regulations and has watched countless videos of human interactions at intersections. Therefore, when the model sees the traffic police raising a hand, it directly outputs an intuitive response based on the rules of the physical world, making a stopping action. This approach makes the vehicle's decision-making more human-like, enabling it to handle complex scenarios that were not preset.

Another core advantage of large model technology lies in its powerful 'zero-shot' or 'few-shot' generalization ability. This means that even if the autonomous driving system has never encountered a particular type of traffic guide attire during training, it can still infer the other party's commanding intentions based on a deep understanding of 'humans' and 'commanding actions.' For instance, in a construction zone, a worker wearing casual clothes but holding a temporary guiding flag still needs to be recognized. Traditional systems might ignore the signal because the target does not conform to the 'uniformed' feature, but a physical world model based on the VLA architecture can comprehensively judge the legitimacy of the signal through context, such as surrounding traffic cones, stalled traffic, and the worker's gaze.

Installing such large models with massive parameters on vehicle chips with limited computational power is a significant challenge. To overcome this, autonomous driving manufacturers adopt 'model distillation' and 'pruning' techniques. This is akin to compressing an encyclopedia into a practical driving manual. In the cloud, autonomous driving systems use ultra-large models for deep learning, capturing the most subtle traffic features; subsequently, through distillation algorithms, this knowledge is transferred to a smaller but highly efficient onboard model. Additionally, innovative frameworks like FastDriveVLA, through 'visual marker pruning' technology, allow the model to focus only on truly important information (such as the traffic police's arm, face, and surrounding obstacles) in each frame and ignore irrelevant background elements, thereby reducing computational load severalfold while maintaining high accuracy.

Decision Arbitration System and Collaborative Control Strategy for Complex Intersections

After the perception system confirms the traffic police's instructions and the large model interprets the semantics, the autonomous driving system enters the most challenging phase: decision execution. At an intersection, a vehicle may simultaneously receive multiple conflicting information sources. For example, the high-definition map indicates a straight-ahead lane, the traffic light is red, but the traffic police waves you through. In such cases, the internal arbitration logic of the autonomous driving system must make an accurate judgment. According to current traffic regulations, the traffic police's commanding authority always supersedes static signal systems and preset rules.

To achieve this high-priority takeover, the decision-making layer of the autonomous driving system adopts a 'hierarchical control architecture.' The top layer is a temporary controller based on traffic police instructions. Once the gesture recognition module confirms a legal passage signal, it sends an override request to the lower-level path planner. This request temporarily invalidates the constraints of traffic lights and generates a temporary trajectory line based on the direction indicated by the traffic police. For instance, when guided by the traffic police to make a left turn, the vehicle automatically adjusts its turning radius and avoids the no-entry zone designated by the traffic police. This process requires extremely precise temporal synchronization, as the traffic police's instructions may change instantaneously, and the system must recalculate the optimal trajectory within milliseconds.

Safety remains the cornerstone of autonomous driving decision-making. If the autonomous driving system recognizes the traffic police waving but cannot interpret the exact semantics, it should adopt a 'conservative response' strategy. In such highly uncertain scenarios, the vehicle must request a human driver to take over; for unmanned Robotaxi vehicles, it must slow down and stop at a safe location while initiating a remote assistance request to the cloud dispatch center, where a human remote safety officer executes the next action. This 'human-machine collaboration' redundancy mechanism is crucial for ensuring that autonomous vehicles do not cause secondary accidents in complex social environments.

Final Thoughts

Recognizing traffic police gestures for autonomous driving systems is not merely a visual challenge. From initial rule-based hardcoding to today's 'intuitive' driving relying on massive data and end-to-end large models, autonomous driving systems are accelerating the transition from 'machines' to 'intelligent agents.' The ultimate goal of this evolution is to enable every autonomous vehicle to make the most accurate judgments at complex intersections, just like experienced drivers.

-- END --