The Forgotten Bangalore in the Tech World

![]() 02/06 2026

02/06 2026

![]() 386

386

Around 2000, the name Bangalore frequently appeared in China's tech parks and policy documents. Located in southern India, nearly on the same latitude as Beijing, the city was hailed as India's Silicon Valley. Outsourcing centers for Microsoft, IBM, and Deloitte dotted the landscape, with hundreds of thousands of Indian programmers writing code, testing systems, and providing customer support for global companies.

Bangalore became a symbol: rise (rise) without relying on resources or capital, but solely on outsourcing.

In China, the slogan "Learn from Bangalore" was repeatedly invoked by tech officials and entrepreneurs.

Several local government plans even explicitly stated the goal to "create China's Bangalore."

But more than two decades later, while Bangalore remains the heart of India's IT industry, China rarely mentions "learning from Bangalore" anymore. As AI, large models, and cloud computing become new buzzwords, the city once revered as a model seems to have been Completely forget (completely forgotten).

Why has Bangalore's luster faded? What path has China's IT industry taken instead?

Bangalore in the 1990s was the poster child for the global outsourcing economy. Giants like Infosys, Wipro, and TCS rose to prominence, undertaking software customization projects for major Western companies. At the time, China had just joined the WTO and stood on the cusp of digitization, eager to integrate with the world.

In this context, a wave of "Learning from Bangalore" quickly spread.

In 2000, the State Council issued the landmark "Several Policies to Encourage the Development of the Software and Integrated Circuit Industries" (commonly known as "Document No. 18"), explicitly elevating software exports and international project contracting to a national strategy.

In 2005, *People's Daily* published reports like "What's the Secret Behind India's Software Industry Rise?" analyzing India's experience. Meanwhile, professional publications like *China Computerworld* focused on the Indian model, delving into CMM certification, software factories, and talent training mechanisms at companies like Infosys and TCS, providing concrete references for China's domestic industry.

Riding this wave, local governments across the country rushed to build software parks, attempting to replicate Bangalore's cluster effect: Dalian was positioned as a "Japan-focused software outsourcing base," while Shanghai Pudong Software Park and Shenzhen Software Park aggressively attracted outsourcing firms. Software parks became new symbols of urban modernization.

Amid this fervor, companies like Neusoft and DHCC became early adopters. DHCC specialized in Japanese software outsourcing, starting with detailed specifications and gradually moving into coding and testing. Neusoft proposed the concept of a "software factory," aiming to standardize and scale operations to secure projects from Europe and the U.S.

Outsourcing seemed a safe path to technology commercialization at the time: no need to risk product failure or spend heavily on marketing. With technical skills and English proficiency, orders could be secured.

Thus, in early 2000s China, cities and companies vied to imitate Bangalore, believing replication would grant entry into the information age.

However, a critical fact was overlooked: Bangalore's success stemmed not just from cheap labor but from decades of accumulated education systems, English proficiency, and global trust networks.

These elements were still immature in China at the time. Few Chinese companies could secure outsourcing contracts, with multinationals still preferring India. Even when orders were obtained, most remained stuck in low-end coding and testing, failing to drive industrial upgrading.

As ideals clashed with reality, China's IT sector began to reflect: Could a nation built on manufacturing and market scale truly replicate Bangalore's outsourcing miracle?

The allure of the outsourcing model lay in its speed, but its fate was inherently short-lived.

During the Bangalore craze of the 2000s, China was seduced by this rapid growth. Urban policies prioritized outsourcing, software parks targeted exports, and talent training emphasized international standards. Within years, outsourcing seemed a shortcut to the information age, allowing cities to hitch a ride on globalization: developed nations outsourced low-value, repetitive coding tasks, while developing nations deployed armies of engineers to complete projects at lower costs.

But China soon paid the price for this invisible contract manufacturing.

After the 2008 financial crisis, global outsourcing orders plummeted, leaving coastal software parks desolate. Companies dependent on project flow suddenly lost their footing. Outsourcing prosperity proved fragile against international market volatility.

To understand this fragility, we must dissect the model's essence.

First, the outsourcing model's export-oriented nature made it vulnerable. Software outsourcing, though high-tech in appearance, was merely another form of contract manufacturing in the digital age. Engineers performed standardized, replaceable tasks with low technical content and minimal innovation. Firms earned revenue through billable hours, not intellectual property. Dependent on global capital flows, the local industry collapsed when international economies contracted. The collective downturn of China's software parks during the crisis revealed the model's inability to generate stable endogenous growth.

Moreover, China's industrial environment and institutional culture differed from India's, making full replication of Bangalore's success impossible.

India's outsourcing triumph relied on its English-language system, Anglo-American educational traditions, and long-standing global trust networks. China's IT ecosystem, rooted in manufacturing and the domestic market, lacked matching linguistic, legal, and business cultural conditions. Mimicking superficial processes was easy; replicating the underlying institutional and cultural foundations proved far harder.

Entering the 21st century, rapid technological iteration propelled the world into the internet era.

The standardized, process-driven "software factory" mindset of outsourcing struggled against the internet's rules of speed and disruptive innovation. Shifts in technological cycles squeezed traditional outsourcing from both ends: fierce price competition in low-end markets and displacement by more dynamic internet models.

IT firms recognized that software outsourcing represented export-driven prosperity, not endogenous growth. It could enrich a city but not sustain a nation's technological future.

By then, clinging to Bangalore's contract manufacturing mindset was no longer wise.

After the flaws of the Bangalore model surfaced, China's IT sector faced new anxieties:

How to position itself in a globalizing world?

After 2008, China's internet narrative took center stage.

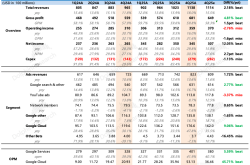

Alibaba finalized its B2B business model, Tencent's QQ surpassed 100 million users, and Baidu went public on NASDAQ.

Dalian's software outsourcing base persisted but was no longer the focal point of China's tech story. The once-revered "Indian model," "CMM certification," and "software factories" faded from view, replaced by discussions of "BAT" (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent), "unicorns," and "mobile internet."

History took a turn here. China did not become the next Bangalore but forged a different path: from outsourcing to ecosystems, from imitation to self-construction.

This shift was both a market imperative and a national strategic choice.

Unlike India's heavy reliance on overseas orders, China possessed a vast, rapidly digitizing domestic market. While Bangalore depended on export orders and cheap labor, Chinese internet firms targeted consumers directly, creating new commercial scenarios. With the world's largest internet user base, the meager profits of outsourcing paled in comparison to domestic market potential. Internet companies discovered that the real goldmine lay in local demand, where innovation meant redefining lifestyles: payments, social networking, e-commerce, mobile services, short videos—none of these bore Bangalore's imprint.

Deeper forces emerged from technology and policy.

Technologically, indigenous innovation became the new buzzword. Huawei made breakthroughs in communications and chips, Alibaba merged e-commerce with cloud computing, and Tencent built a social ecosystem and digital finance platform. A cohort of globally competitive tech firms rose rapidly, instilling industrial confidence rooted in internal growth rather than external service.

Policy-wise, the national strategy of technological self-reliance guided firms to shift from dependent growth to core innovation. Capital, talent, infrastructure, and industrial policies were systematically integrated, providing robust support for autonomous tech development. When societal resources prioritized core technology breakthroughs, outsourcing-driven growth naturally marginalized.

Thus, market demand, technological accumulation, and policy guidance converged to propel China's IT industry along a path distinct from Bangalore: a trajectory of independent innovation grounded in local strength yet globally influential.

Today, Bangalore remains an indispensable link in the software supply chain but is no longer a global innovation hub. The outsourcing miracle once imitated and deified has faded from mainstream tech discourse.

China, meanwhile, has completed its narrative of technological independence:

Beijing leads in research, Shenzhen in manufacturing, and Hangzhou in algorithms.

This forgotten craze for Bangalore may mark the true awakening of China's tech industry.