Avoiding Japan's AI Pitfalls: Lessons for China

![]() 06/06 2025

06/06 2025

![]() 614

614

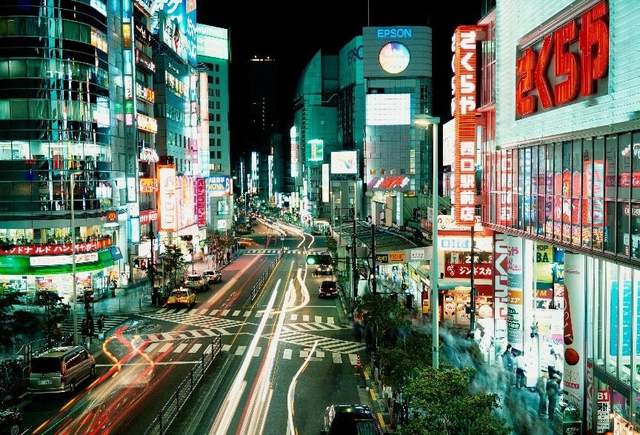

Last year, while casually browsing the Yomiuri Shimbun provided by my hotel in Japan, I was struck by the abundance of articles on AIGC. From technology to applications, and from industrial chain integration to government policies, the newspaper painted a picture of a nation brimming with expectations for AI.

However, despite these expectations, anyone with even a cursory understanding of Japan's current technology industry knows that, for years, Japan's AI initiatives have been loud but ineffective.

Japan has not only failed to develop a large model like DeepSeek that could influence the global AI landscape but has also struggled to promote even basic AI applications. Ironically, the Japanese government only announced the elimination of 3.5-inch floppy disks from all government processes a year ago. Imagine relying on floppy disks to develop large models; it would be a steampunk nightmare.

However, in contrast to the current state of Japanese AI, Japanese AI was once formidable and was even the only force that could compete with American AI during the last AI renaissance.

Times have changed, and the once-dominant AI force has become a technological underdog, inevitably evoking a sense of nostalgia.

But beyond sentimentality, the setbacks of Japanese AI bring me more vigilance and concern. Because during the heyday of Japanese AI in the 1970s and 1980s, many of its industrial characteristics were strikingly similar to today's Chinese AI.

As more and more people begin to learn from Japan's experience in combating the bursting of the real estate bubble and long-term economic downturn, we may also need to take an additional lesson: seeing clearly the traps Japan fell into in its AI development and reminding ourselves not to repeat the same mistakes.

The current cycle of deep learning and large models is widely considered the second AI renaissance. The first AI renaissance was centered on expert systems in the 1970s.

At that time, large computers were at the forefront, and for the first time, people could build knowledge bases by storing information in computers. Some believed that if the knowledge base accumulated to a huge extent, the computer would become an omniscient god, and AI would be realized. Surprisingly, this idea is quite similar to today's optimistic imagination of large models.

Returning to the 1970s, Japan had an advantage in basic fields such as storage and was heavily invested in the mainframe field, embarking on one megascale AI project after another. The most representative of these was the "Fifth Generation Computer."

In October 1981, Japan announced the initiation of the development of the Fifth Generation Computer and formulated a ten-year "Fifth Generation Computer Technology Development Plan" in April 1982 with a total investment of 100 billion yen. The "Fifth Generation Computer" was the largest AI expert system at that time, envisioned to possess functions such as answering questions, knowledge base management, image recognition, and code generation, which could help Japan achieve grand goals like predicting earthquakes and calculating skyscraper structures. It was expected to be "40 years ahead of its time" upon completion.

This "nationwide AI" project, aiming to accomplish everything in one fell swoop, had a gambling aura. When the "Fifth Generation Computer" was first proposed, Japanese society was generally in a stage of extreme confidence in the prospects of AI technology and Japan's national strength. No one imagined what would happen if the project failed, who would bear the consequences, or if there were alternative plans.

Subsequently, the "Fifth Generation Computer" did indeed trigger the United States to initiate an AI competition focusing on expert systems and mainframe projects. However, the sudden rise of home computers led the United States down the path of the information revolution dominated by the internet. Conversely, Japan announced in 1992 that the Fifth Generation Computer project was unable to achieve the expected goals and could not pass the acceptance inspection.

Over-investment in large AI projects like the Fifth Generation Computer made the Japanese AI system exceptionally closed. The state and large companies dominated the development of AI projects, and small and medium-sized enterprises and individual developers could not participate. Therefore, once the core projects failed, the entire country's AI development path was pushed into a dead end. At the same time, this nationwide AI model, which invested the vast majority of resources into a handful of projects, also led to insufficient inclusiveness in Japan's AI industry, making it unable to agilely and flexibly capture new opportunities and tolerate innovative trial and error.

The ultimate result was that when the economic bubble burst, the Japanese economy suddenly fell into recession. The once-proud AI could not become a lifeline to help Japan's economy navigate the storm but merely became an insignificant casualty. When AI became a development opportunity again decades later, Japanese society lost the courage to embrace AI once more.

We might as well compare this to the rise of Chinese AI today. How many people eagerly hope to develop AI technology through a nationwide system? They hope that DeepSeek or some national AI project, or some large technology company, can accomplish everything in one fell swoop. But who will bear the cost if "nationwide AI" becomes a trap?

Every technological competition in history has proven that inclusiveness, openness, and freedom, even tolerating some gray areas, can create fertile soil for technological development.

"Too rigid and easy to break" is an elegy for Japanese AI. Let's just leave it in Japan.

Comparing the current development situation of AI between China and the United States, it is easy to find one difference: China places more emphasis on the direction of industry + AI, while the United States has barely made a splash in this field.

No one can stand in the future to point out which AI path is correct. But unfortunately, Japan once also valued industrial AI and undervalued the consumer market for AI technology.

It must be stated that there is no intention to deny the industrial AI path here. In fact, we have always believed that the lack of enthusiasm for industrial intelligence in Europe and the United States stems from deep-seated issues in their industrial structure and social power. This has opened up a huge window of opportunity for China. What I really want to discuss is that it is not difficult to find from Japan's AI experiences and lessons that the industrial AI market can easily create a huge false prosperity, thereby confusing the true progress of technological development.

In the 1980s, various industries in Japan were generally dominated by local large companies. These enterprises belonged to different financial groups and corporations, and their interest links with technology enterprises were intricate. Therefore, when a technology was highly praised by the government and the public, large technology companies could easily create an illusion of "AI has brought tremendous value" in various industries through their own interest networks. After all, whether AI technology is useful in a closed industry may be decided by one or two people, but whether it is useful in the consumer market needs to be decided by thousands or even tens of thousands of people.

Another hidden concern about Japan's emphasis on industrial AI is that to implement AI, companies have invested huge costs in related fields. After actual use, these systems quickly become obsolete and require even greater operational and maintenance costs. After the economic bubble burst, the development of science and technology in Japan was difficult. An important reason was the need to spend manpower and material resources to maintain those outdated systems. The once-proud AI dream turned into a drain on Japanese technology under human factors and interest transfers.

Looking back at today's China, it is found that many industries have similar situations. Under the current major policy trend, China is currently using AI in thousands of industries, and many industries have their own indicators and tasks for using large models. Among them, it is difficult to distinguish which ones have truly achieved intelligence and which ones are for perfunctory reasons and political achievements.

The industry is closed and can be falsely reported. AI can be proven useful for many purposes, but in the real consumer market, some false decencies will disappear instantly.

For AI, it is better to have a true but battered body than a false but beautiful appearance.

No one loves robots more than the Japanese.

In 1973, Waseda University announced the creation of WABOT-1, the world's first autonomously moving humanoid robot, causing a sensation throughout Japan and even the world.

From Astro Boy to Gundam, Japanese pop culture repeatedly showcases its obsession with robots. Over time, robots seem to have become a spiritual anchor for the Japanese. When AI was just emerging, the entire country naturally believed that robots would soon succeed, so a large amount of research and development efforts were poured into the field of robotics. For example, the WABOT-1 mentioned above consumed millions of dollars in research and development funds. Large technology companies, startups, and universities all joined the surging wave of robotics. Moreover, most robot and robot dog projects were carried out under the name of AI. For example, Sony's AIBO, an electronic pet launched in 1999, featured AI recognition capabilities as one of its main selling points.

But what was the result? The robot projects created during the heyday of Japanese AI generally had two characteristics: they were extremely expensive and extremely useless.

The underlying logic behind this situation is that AI is not equal to robots. Whether it is the AI fever of the 1970s and 1980s or today's AI renaissance, no AI technology has been developed with a humanoid robot as the design blueprint so far. AI interaction that can be accomplished with a computer, a mobile phone, or a camera is unnecessarily and painstakingly installed in a humanoid body. To put it nicely, it satisfies the scientific fantasy imprinted in human DNA; to put it bluntly, it's just a waste of time.

The subsequent result was that Japan invested a lot of resources in the almost unproductive field of robotics, gaining a false reputation for loving and being skilled in robotics, but in exchange, it fell behind in the systematic development of its social and economic system since the beginning of the information revolution.

After being sarcastic for a while, you may have guessed what I want to say. Today's AI route supported by deep learning and pre-trained large models is also not inherently related to humanoid robots. How much of the so-called embodied intelligence boom is a conduction effect between technologies? How much is it a story told to the public and investors, leveraging the psychological anchor points brought by science fiction culture?

If humanoid robots can succeed, then let it happen naturally without investing huge resources to force their maturity.

If there is little hope for humanoid robots, then why not focus on Chinese science fiction, which might even yield better returns?

After falling into an economic recession, although Japan has repeatedly proposed technological revitalization and AI revitalization, its society and economy have lost the interest and courage to invest in cutting-edge technologies like AI. Coupled with the high costs required to maintain Japan's ancient IT systems and facilities, the vitality of economic innovation has been drained by the old systems, leaving very limited resources for innovation. At the same time, the government is also unable to formulate support policies that benefit innovative industries such as AI, and instead extracts heavy taxes from such technology industries.

Under multiple factors, Japanese AI eventually turned into ashes. But we do need to see that this ash was once a dazzling flame, and its combustion mechanism is very similar to today's Chinese AI. Instead of conducting a large number of comparative studies between Chinese and American AI, we should often look at the AI industries of Japan, Europe, and even the Soviet Union, which once competed with the United States but ultimately failed. Their lessons and experiences are our chips to reduce trial and error.

Of course, Chinese AI is also very different from the Japan of the past.

For example, China has a sufficiently large domestic demand market. Whether it is industrial or consumer demand for intelligence, Japan can only highly rely on exports, and the export targets are major competitors such as the United States and Europe. In contrast, China has a sufficiently large industrial chain and consumer market to absorb AI technology. Chinese AI has the political and economic guarantee to boldly go abroad and does not rely heavily on the global market for recovery.

Today's Chinese AI industry is built on the foundation of communication, IT, internet, and cloud computing enterprises, which mirror the structure of American tech giants, embody the innovative spirit of Silicon Valley, and wholeheartedly embrace open-source and open technology cultures. This open approach stands in stark contrast to the insular nature of Japanese tech companies. DeepSeek's success in the open-source realm underscores the fact that embracing openness is essential for the strength of Chinese AI.

Moreover, China's confidence in AI and technology transcends mere economic motivations. While this dual-edged sword has its pros and cons, it fortuitously shields China from the risk of AI collapse faced by Japan during economic downturns. When public expectations, pride, and faith coalesce around AI, the soft power it generates is immense and immeasurable.

Comparing Japan's once-mighty but declining AI industry with China's burgeoning one reveals both similarities and differences. At its core lies the necessity of fostering an inclusive environment within the AI sector. It is imperative to ensure that AI can develop unfettered and fully realize its market value, thereby steering clear of the pitfalls of isolation and eventual failure.

The genuine path to AI advancement involves opening up to the public, integrating into corporate ecosystems, dismantling technical closed-source practices, and embracing change at every turn.

In an era where technological autonomy and controllability are paramount, it's crucial to recognize that China's indigenous technology aspirations are rooted in contributing the best to the world, not in isolating itself. To sail the vast oceans, one must harness winds from all directions.

Japan's AI, once powerful yet isolated, ultimately withered away amidst historical frosts and snows. To avoid this fate, China's AI must ensure its roots remain intertwined with a source of freedom, openness, and inclusivity.