Has AI Reached Its Peak? OpenAI's Chief Scientist Says No, Industry Shifts from Stacking Compute Power to Pursuing Intelligence Density

![]() 12/01 2025

12/01 2025

![]() 449

449

Has artificial intelligence reached its peak? The 'AI Progress Slowdown Theory' has surfaced frequently over the past year.

Lukasz Kaiser—co-author of the Transformer paper, Chief Research Scientist at OpenAI, and one of the core architects of reasoning models—recently offered a starkly different perspective on the Mad podcast.

He mentioned that AI development is not slowing down but is still accelerating along a stable and sustained exponential curve. The perceived 'stagnation' stems from a shift in the nature of breakthroughs. The industry has moved from solely building 'larger models' to constructing smarter, more cognitive models.

In his view, pre-training remains crucial but is no longer the sole engine. The emergence of reasoning models acts like adding a 'second brain' to foundational models, enabling them to deduce, verify, and self-correct rather than merely predicting the next word. This means models achieve greater capability jumps at the same cost and deliver more reliable answers.

However, AI's 'intelligence landscape' remains highly uneven. Lukasz admitted that the strongest models can solve International Mathematical Olympiad problems but may struggle to count objects in a children's puzzle. They can write code surpassing professional programmers yet still misjudge spatial relationships in a photo.

Meanwhile, the new paradigm brings fresh commercial realities. With hundreds of millions of users, cost efficiency now trumps raw compute stacking. Model distillation has shifted from an 'option' to a 'necessity.' Whether small models can replicate the wisdom of large ones determines AI's true accessibility.

In this interview, Lukasz not only refuted the 'AI slowdown theory' but also outlined a future marked by greater refinement, intelligence, and multi-layered progress: foundational models continue expanding, reasoning layers evolve persistently, multimodality awaits breakthroughs, and efficiency battles at the product level have just begun.

Below is the full, organized interview transcript. Enjoy~

/ 01 /

AI Isn't Slowing Down—You Just Aren't Looking Closely Enough

Host: Since the beginning of the year, there has been a persistent view that AI development is slowing down, that pre-training has hit a ceiling, and that the scaling laws seem to have reached their limits.

Yet, as we recorded this episode, the AI community witnessed a flurry of major releases: GPT-5.1, Codex Max, GPT-5.1 Pro, Gemini Nano Pro, and Grok-4.1 all debuted nearly simultaneously, seemingly shattering the narrative of 'AI stagnation.' What progress signals, invisible to outsiders, have you and other experts at the forefront of AI labs observed?

Lukasz: AI technological progress has consistently followed a very steady exponential trajectory in terms of capability improvement—that's the overarching trend. New breakthroughs emerge continuously, driven by new discoveries, increased computing power, and better engineering implementations.

In language models, the advent of the Transformer and reasoning models represent two major turning points, with development following an S-shaped curve. Pre-training sits in the upper segment of the S-curve, but scaling laws haven't failed—loss continues to decline logarithmically-linearly with computing power, as validated by Google and other labs. The real question is: how much money must you invest, and is it worth the return?

The new reasoning paradigm resides in the lower segment of the S-curve, where the same cost yields greater returns because vast discoveries remain untapped.

From ChatGPT 3.5 to the present, the core shift is that models no longer rely solely on memorized weights to output answers. Instead, they can search the web, reason, analyze, and then provide correct responses.

For example, the old version would fabricate answers to questions like 'What time does the zoo open tomorrow?' by recalling outdated information from five years ago on the zoo's website. The new version can access the zoo's website in real time and cross-verify information.

ChatGPT or Gemini already possesses many underrecognized capabilities. You can photograph a broken item and ask how to fix it—it will guide you. Give it university-level assignments, and it can complete them.

Host: I certainly agree with that. There are indeed many obvious areas for improvement—'low-hanging fruits' easily seen and addressed. For instance, models sometimes exhibit logical inconsistencies, make tool-calling errors, or fail to remember long conversations. These are issues the industry recognizes and is actively working to resolve.

Lukasz: Absolutely. There's a massive amount of extremely obvious room for improvement. Most fall under engineering-level issues: laboratory infrastructure and code optimization. Python code often runs but inefficiently, impacting result quality. In training methods, reinforcement learning (RL) proves trickier and harder to implement well than pre-training. Additionally, data quality remains a bottleneck.

We previously relied on raw internet data warehouses like Common Crawl, requiring substantial effort to clean and refine raw web data. Today, major companies have dedicated teams to enhance data quality, but truly extracting high-quality data remains time-consuming and labor-intensive. Synthetic data is emerging, but every step—from generation to model selection to engineering implementation—demands meticulous attention to detail.

On another front, multimodal capabilities face challenges. Models currently lag far behind textual maturity in processing images and sounds. While the improvement direction is clear, achieving substantive breakthroughs may require training entirely new generations of foundational models from scratch—a process demanding months and enormous resources.

I often wonder: How powerful can these improvements truly make the models? Perhaps that's an underestimated question.

/ 02 /

AI Learns to 'Self-Doubt': GPT Begins Correcting Its Own Mistakes Proactively

Host: I'd like to revisit reasoning models, as they're still so new. Many people don't fully grasp how they differ from foundational models. Could you explain the distinction in the simplest terms?

Lukasz: Before providing a final answer, reasoning models internally deliberate, forming a 'chain of thought' and leveraging external tools like search to clarify their reasoning. This enables them to actively seek information during thinking, delivering more reliable answers. That's the visible capability.

Their greater strength lies in focusing learning on 'how to think' itself, aiming to discover superior reasoning paths. Previous models trained primarily by predicting the next word, but this method proves ineffective for 'reasoning' because reasoning steps can't directly compute gradients.

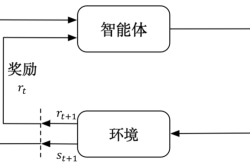

Thus, we now train them using reinforcement learning. This involves setting a reward objective, letting the model repeatedly experiment, and discerning which thinking approaches yield better outcomes. This training method is far more demanding than previous approaches.

Traditional training tolerates lower data quality, generally functioning regardless. Reinforcement learning, however, demands extreme caution, requiring careful parameter tuning and data preparation. Currently, a foundational method involves using data with clear right/wrong judgments, such as solving math problems or writing code—hence its exceptional performance in these domains. Progress in other areas exists but hasn't reached the same level of stunning (jīngyàn, 'astonishing') yet.

How to implement reasoning in multimodal contexts? I believe we're just beginning. Gemini can generate images during reasoning, which is exciting but still very primitive.

Host: A common perception exists that pre-training and post-training are disjointed, with post-training equating nearly to reinforcement learning. Yet, reinforcement learning already participates during pre-training—we just didn't recognize it then.

Lukasz: Pre-trained models existed before ChatGPT but couldn't hold genuine conversations. ChatGPT's key breakthrough was applying RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback) to pre-trained models. RLHF trains models by having them compare different responses and learn which options humans prefer.

However, excessive RLHF training can make models overly 'eager to please,' rendering their core fragile. Despite this, it remains central to achieving conversational abilities.

The current trend shifts toward larger-scale reinforcement learning. While data volumes still lag behind pre-training, this approach builds models capable of judging correctness or preference. This method currently suits domains with clear evaluative metrics and can incorporate human preferences for more stable long-term training, preventing scoring system failures.

In the future, reinforcement learning could expand to more general data and broader domains. The question remains: Do certain tasks truly require extensive thinking? Perhaps they do—or maybe we need even more thinking and reasoning than currently employed.

Host: To enhance reinforcement learning's generalization, does better evaluation lie at the heart? For instance, your cross-economic domain evaluations test performance across scenarios—is such systematic measurement truly essential?

Lukasz: People usually think before writing, albeit less rigorously than solving math problems, but always with a rough mental plan. Models currently struggle to fully simulate this process, though they're beginning to attempt it. Reasoning capabilities can transfer—for example, once a model learns to check websites for information, this strategy applies to other tasks. However, visual reasoning training remains vastly insufficient.

Host: How exactly do chains of thought operate? How do models decide to generate these reasoning steps? Are the intermediate inferences we see on-screen their true, complete thought processes? Or do more complex, extended reasoning chains lie hidden behind?

Lukasz: The chain-of-thought summaries you see in ChatGPT are actually distillations of the full thought process by another model. The original reasoning chains tend to be verbose. Simply having models attempt step-by-step thinking after pre-training can generate some reasoning steps, but the key goes deeper.

We train models this way: First, let them explore multiple thinking approaches, some yielding correct results, others errors. Then, we select the thinking paths leading to correct answers and instruct the model, 'This is how you should think.' This is where reinforcement learning comes into play.

This training genuinely transforms the model's thinking patterns, with effects already visible in mathematics and programming. The greater hope is extending this to other domains. Even in math problem-solving, models now learn to proactively self-correct errors—a capacity for self-verification that naturally emerges from reinforcement learning. Essentially, models learn to doubt their own outputs and reconsider when something feels amiss.

/ 03 /

Pre-training Remains a Power-Hungry Beast: RL and Video Models Vigorously Compete for GPU Resources

Host: Let's discuss the transition from Google to OpenAI and the cultural differences between the two.

Lukasz: Ilya Sutskever, my former manager at Google Brain, left to co-found OpenAI. He asked me several times to join during those years. Then the Transformer paper came out, followed by the pandemic. Google completely shut down and restarted very slowly.

As a small team within a large company, Google Brain's working atmosphere differed greatly from a startup's.

Ilya told me OpenAI, while still early-stage, was working on language models—potentially aligning with my interests. I thought, 'Well, why not give it a try?' Before this, I'd only worked at Google and universities. Joining a small startup was indeed a major shift.

Overall, I find that similarities between different tech labs outweigh people's perceptions. Differences exist, but from the perspective of a French university, the gap between any university and a tech lab far exceeds the differences among labs themselves. Whether large companies or startups, their shared emphasis on 'delivering results' makes them more alike.

Host: How is OpenAI's internal research team organized?

Lukasz: Most labs pursue similar work: improving multimodal models, enhancing reasoning capabilities, optimizing pre-training, or upgrading infrastructure. Dedicated teams usually handle these areas, with personnel occasionally rotating. New projects launch regularly, such as diffusion models. Some exploratory projects scale up—video models, for instance, demand more participants.

GPU allocation primarily follows technical needs. Currently, pre-training consumes the most GPUs, so resources prioritize it. Reinforcement learning and video models' GPU demands are also growing rapidly.

Host: What lies ahead for pre-training in the next year or two?

Lukasz: I believe pre-training has technically entered a steady development phase. Investing more computing power still yields improvements—valuable, though less dramatic than reasoning advancements. It genuinely enhances model capabilities, warranting continued investment.

Many overlook a key shift: Years ago, OpenAI functioned purely as a research lab, concentrating all computing power on training and unhesitatingly creating GPT-4. Times have changed. ChatGPT now serves one billion users daily, generating massive conversational demands that require substantial GPU resources. Users resist paying excessively per conversation, compelling us to develop more economical small models.

This transformation affects all labs. Once technology becomes productized, cost considerations become unavoidable. We no longer pursue only the largest models but strive to deliver equivalent quality through smaller, cheaper alternatives. The pressure to reduce costs while maintaining performance is very real.

This has reignited interest in distillation techniques—transferring knowledge from large models to smaller ones to ensure quality while controlling expenses. Although distillation existed earlier, economic pressures made its value truly apparent only now.

Of course, training enormous models remains vital, as they form the basis for high-quality distilled small models. With sustained industry GPU investment, another wave of pre-training advancements is likely. Essentially, these changes represent adjustments along the same technological evolution path, shaped by varying resources and demands at different stages.

The crucial insight is that pre-training remains effective and complementary to reinforcement learning. Running reasoning on more powerful foundational models naturally yields better results.

Host: Modern AI systems evolve through a blend of laboratory research, RL, and numerous technologies. During the deep learning era, people often claimed to understand AI at a micro level—e.g., matrix multiplications—but didn't fully grasp how components interacted. Over the past few years, substantial work on explainability has occurred, particularly for complex systems. Are model behaviors becoming clearer, or do black-box elements persist?

Lukasz: I believe both perspectives hold merit. Fundamentally, our understanding of models has advanced significantly. A model like ChatGPT converses with countless people, drawing knowledge from the entire internet—obviously, we can't fully comprehend everything happening internally, just as no one understands the entire internet.

Yet we've made new discoveries. For instance, a recent OpenAI paper demonstrated that if you make many of a model's connections sparse and unimportant, you can more clearly track its specific activities during task processing.

Thus, by focusing on internal model research, we do gain substantial understanding. Numerous studies now explore how models work internally, and our cognition of their high-level behaviors has progressed considerably. However, most of this understanding comes from smaller models. It's not that these principles don't apply to large models, but large models process too much information simultaneously, and our comprehension remains limited.

/ 04 /

Why can GPT-5 solve Olympiad problems but fail at math problems for 5-year-olds?

Host: I want to talk about GPT-5.1. What has actually changed from GPT-4 to 5 to 5.1?

Lukasz: That's a tough question. From GPT-4 to 5, the most crucial change was the integration of reasoning capabilities and synthetic data, along with a significant cost reduction in pre-training. By GPT-5, it had become a product used by a billion people. The team continuously adjusted between safety and friendliness, making the model's responses more reasonable across various issues—neither overly sensitive nor randomly rejective. While hallucination issues still exist, they've improved significantly compared to before through tool validation and training optimization.

Host: GPT-5.1 primarily focuses on post-training improvements, such as incorporating different tone styles ranging from nerdy to professional. This is likely a response to some people missing the pleasing characteristics of earlier models. Adding more tonal variations falls under post-training. Do you teach the model response styles by showing examples, which resembles supervised learning, or train it with rewards for right and wrong answers like reinforcement learning?

Lukasz: I don't directly handle post-training, but this area is indeed a bit odd. The core is reinforcement learning. For example, you'd judge, 'Does this response carry sarcasm? Does it meet requirements?' If the user requests sarcasm, the model should respond accordingly.

Host: I feel reinforcement learning plays a significant role in model iteration. Other companies usually align models with pre-training when releasing them, sometimes producing multiple models from a single pre-training. Previous version naming often aligned with technology, like o1 for pre-trained versions and o3 for reinforcement learning versions. People found this naming confusing. Now, it's renamed based on capabilities: GPT-5 is the foundational version, and 5.1 is the enhanced version—lighter, slightly weaker but faster and cheaper.

Lukasz: Reasoning models focus on complex reasoning. Decoupling naming from technology brings flexibility. As OpenAI grows, it has many projects—reinforcement learning, pre-training, website optimization, etc. Model distillation allows us to integrate results from multiple projects without waiting for all to complete simultaneously. We can regularly integrate updates, which is great for users who no longer need to wait months for new pre-trained models.

Host: Users can control the model's thinking time. How does the model decide by itself how long to think under default settings?

Lukasz: The model decides its thinking duration when encountering a task, but we can guide it to think deeper by providing extra information. Now, you do have some control over it. The more fundamental change is that reasoning models consume more tokens to think, and their capability improvement rate far exceeds that of pre-training. If GPT-5 thinks for a long time, it can even solve math and informatics Olympiad problems, showcasing remarkable potential.

However, current reasoning training mainly relies on scientific domain data, which is far less extensive than pre-training data. This results in highly uneven model capabilities—exceptional in some areas but poor in adjacent ones. This contradiction is common: for example, the model can solve Olympiad problems but may fail at first-grade math problems that humans can solve in ten seconds. Remember: the model is powerful but also has obvious shortcomings.

Let me give a thought-provoking example. Using Gemini, look at two sets of dots to judge parity: in the first question, each side has several dots with one shared in the middle; the correct answer should be odd. Gemini 3 answered correctly. But then, a structurally similar question appeared, and it completely ignored the shared dot, directly judging it as even despite just seeing a similar scenario.

The same question given to GPT-5.1, it solved the first question but misjudged it as even. If switched to GPT-5 Pro, it would spend 15 minutes running Python code to count the dots, while a five-year-old could answer correctly in 15 seconds.

Host: So what's holding the model back?

Lukasz: Multimodality is still in its early stages. The model's ability to solve the first example shows progress, but it hasn't truly mastered reasoning in multimodal contexts. While it can learn from context, it doesn't effectively borrow reasoning strategies from the context to advance. These are known bottlenecks, primarily due to insufficient training.

But a deeper issue is that even with improved multimodal capabilities, the model might still struggle with math problems like those my daughter does. These problems aren't purely visual; the model hasn't learned to apply reasoning at a simple abstract level. It gets stuck on recognizing pixel patterns in dot matrices, failing to see abstract logic like 'both sides have the same quantity but share one dot, so the total is odd.' This ability to abstract from images to symbols hasn't been established yet.

Thus, these questions actually expose a fundamental limitation of reasoning models: they haven't automatically transferred chain-of-thought strategies learned from text, like 'calculate the total first, then judge parity,' to visual inputs. This is the core challenge for multimodal reasoning to overcome.

Another detail: these questions seem simple to humans, but the model must first recognize 'dots' and 'sharing' concepts from pixels. If dot size, spacing, or color varies in the image, the model might not recognize key elements at all.

Compared to symbolically clear math problems, visual tasks lack robust foundational recognition. When the model fails on the second example, it's likely because it didn't correctly recognize the 'shared dot' visual information. This indicates that the bottleneck in multimodal reasoning lies not just in logic but also in cross-modal semantic alignment.

Early childhood math problems are cleverly designed. These seemingly simple questions integrate multiple cognitive processes like abstraction, analogy, counting, and parity judgment. The model might correctly identify dot counts in one step but err in judging parity. By tracking the model's confidence at each step, we found its certainty in 'identifying shared dots' significantly dropped in the second example, indicating unstable generalization of visual patterns. This points us toward improvement: training needs more visual reasoning examples involving 'shared elements' and 'set operations.' We expect this specific issue to improve within six months.

From a macro perspective, the problems we're discussing, including multimodal reasoning, are solvable engineering challenges, not fundamental theoretical obstacles. The core lesson is that reasoning models will continue to exhibit 'jagged' capability curves across domains, but the depth of these jagged edges will gradually decrease with training and distillation.

Host: This GPT-5.1 update feels like releasing a Pro product. What's the most crucial new capability?

Lukasz: The most critical improvement is a more natural conversation interface. Now, the system automatically adjusts response length based on your intent, eliminating the need to manually choose short, medium, or long replies. This relies on reinforcement learning in post-training, where reward signals are no longer simple right/wrong judgments but based on 'user satisfaction.' They trained reward models on vast amounts of real conversations to capture subtle interaction metrics. This way, the model learns to elaborate more on complex questions and be concise with simple ones.

This is also an evolution of RLHF—from learning human preferences to learning what satisfies users. The model can also self-assess confidence during generation. If certainty is high, it ends the response early, saving computational resources. However, these belong to infrastructural optimizations that don't directly boost core reasoning capabilities. The real progress comes from improved post-training data quality, especially incorporating more edge cases like 'saying I don't know' and 'asking for confirmation,' making the model more cautious. Version 5.1 is merely a productized snapshot of their overall reasoning research.

Host: Is o4-mini's reasoning ability genuinely stronger, or is it an evaluation issue?

Lukasz: Many ask about the difference between o4-mini and o3. They're not simple upgrades but different design choices. o3 showcases our pursuit of extreme reasoning capabilities in reinforcement learning, while o4-mini represents a 'refined compression'—achieving similar effects with fewer resources. The key difference lies in 'computational volume during reasoning': o3 invests heavily in computation when answering, whereas o4-mini relies on more thorough optimization during training.

In practical use, o4-mini appears more 'usable' in most daily scenarios due to incorporating more general data like long conversations and tool usage. However, for truly complex logic or mathematical proofs, o3 remains stronger. The ideal approach is to use mini for general tasks and switch to Pro for deep reasoning.

We're also seeing a trend: 'autonomous research' is blurring the lines between training and reasoning. Models can now not only answer questions but also design experiments, write code, analyze results, and even generate their own training data, forming a self-improving loop. This is our core direction toward 2026.

I believe the true AGI milestone is when models can autonomously discover new algorithms, not just complete existing tasks. This requires reinforcement learning to support 'exploring the unknown,' not just verifiable tasks. We've already conducted internal experiments where models perform 'hypothesis-experiment' cycles in simulated environments, currently discovering simple mathematical theorems—though very primitive. But maybe one Monday morning, we'll find it proved a new theorem over the weekend. That moment might mark the beginning of AGI.

/ 05 /

GPT-5.2 may overcome AI's biggest flaw: learning to say 'I don't know'

Host: What excites you most in the next 6–12 months?

Lukasz: What excites me most is that multimodal reasoning is maturing. When AI can understand images and language simultaneously, it will truly empower fields like robotics and scientific research. It won't just guess words but begin simulating real-world logic in its mind. Another positive is that reasoning costs are dropping rapidly—future versions might even run on smartphones, giving everyone a true personal AI assistant.

The scientific domain might be disrupted first, similar to AlphaFold 3 and new material research. Language models won't just analyze data but actively propose hypotheses, design experiments, and interpret results. I speculate that by late 2026, we might see the first top-tier journal paper where AI proposes the core hypothesis and humans mainly verify it. That would be a historic moment.

Of course, challenges remain. The key is to teach AI to 'recognize what it doesn't know' and ask questions proactively instead of confidently making up nonsense—a current focus of reinforcement learning. Hopefully, by the time we discuss GPT-5.2, it will bring surprises in this area.

Host: What would you like to say to the audience?

Lukasz: AI development never stops; it just changes direction. If you feel overwhelmed, don't worry—no one can keep up entirely. The most astonishing applications often come from non-technical users who employ it in ways we didn't anticipate.

These issues will improve over time. A deeper problem lies in whether new challenges will emerge as fields like multimodality progress. We're continually seeking typical cases. While technological frontiers shift and certain processes become smoother, the key is whether entirely novel challenges arise. For example, if a tool changes from three teeth to four, people don't need to relearn the entire usage method.

I'm excited about generalization capabilities, considering it the core issue of machine learning and intelligent understanding. Pre-training differs because it mainly accumulates knowledge by scaling models and data rather than directly enhancing generalization. But true understanding should boost generalization.

The critical question is: Is understanding itself sufficient for powerful generalization, or is a simpler approach needed?

I believe the priority is to simplify the understanding process—that's the direction I'm passionate about. Current models still have limitations: they lack physical world experience, insufficient multimodal capabilities, and immature understanding mechanisms.

After breaking through these bottlenecks, we'll face a more fundamental question: Do we need entirely new architectures enabling models to autonomously grasp core patterns without learning every detail through massive data?

The best way to explore this question is to first solve all related sub-problems. Like driving in thick fog, you can't predict obstacle distances. We're moving forward rapidly and learning much in the process. The core challenge is achieving few-shot learning—the ability to generalize like children, which even the most powerful current models haven't achieved.

While advancing theoretical generalization, another key issue is architectural innovation. Beyond Transformers, many directions warrant exploration. Though some small models excel in specific tests, overall breakthroughs remain to be seen. Different research teams are driving foundational scientific progress—work that may not frequently appear in news but is crucial.

The development of computational resources is equally vital: more powerful GPUs make running experiments more feasible, promoting research progress. However, design remains the primary bottleneck. While AI coding assistants help implement ideas, having models execute tasks requiring long-term feedback—like week-long experimental processes—still faces challenges. This involves memory management issues, such as compressing key information to break context limits, but this capability requires specialized training.

Another important direction is connecting models with external tools. Current models can already use web searches and Python interpreters, but safely granting system permissions remains difficult. As model capabilities expand into math, science, and even finance, people naturally wonder: Could a universal model handle all tasks?

From a product perspective, we need to maintain human-centric values in technology. Current models still require fine-tuning, but the progress speed is encouraging. Take machine translation as an example: while GPT-4 is accurate enough for most scenarios, people still prefer human translation for important documents—essentially a trust issue. Certain jobs will continue being done by humans, but that doesn't mean societal efficiency won't improve.

In frontier research directions, I'm particularly focused on unified cross-domain learning capabilities. Robotics will be a crucial litmus test for multimodal abilities. When models truly understand the physical world, household robots might bring more significant societal impact than chatbots.

These breakthroughs will profoundly change our worldview. Though the path is challenging, I believe we're steadily progressing toward this direction.

By Lin Bai