AI Bubble Original Sin: Is NVIDIA an Addictive 'Poison Pill' for AI?

![]() 12/03 2025

12/03 2025

![]() 440

440

Marked by the release of ChatGPT at the end of 2022, the AI frenzy over the past three years has seen a speculative frenzy across every segment, from computing power, storage, networking, manufacturing, power infrastructure, software applications, to even edge devices.

However, as the third anniversary approaches, when the pillars of AI infrastructure announced unprecedented large-scale AI infrastructure projects around the time of their third-quarter reports, the market suddenly seemed to lose its soul, beginning to worry about an AI investment bubble.

While some in the industry have made a fortune, others have suffered losses to the point of frantically seeking financing. Where does the problem lie? Why is financing so dazzlingly complex and varied?

In this piece, Dolphin Research carefully examines these issues through the financial statements of core companies in the industrial chain, attempting to understand whether AI investment has truly reached a bubble stage. If there is indeed a bubble, where does its original sin lie?

I. Dazzling Financing? Severe Distortion in Industrial Chain Profit Distribution

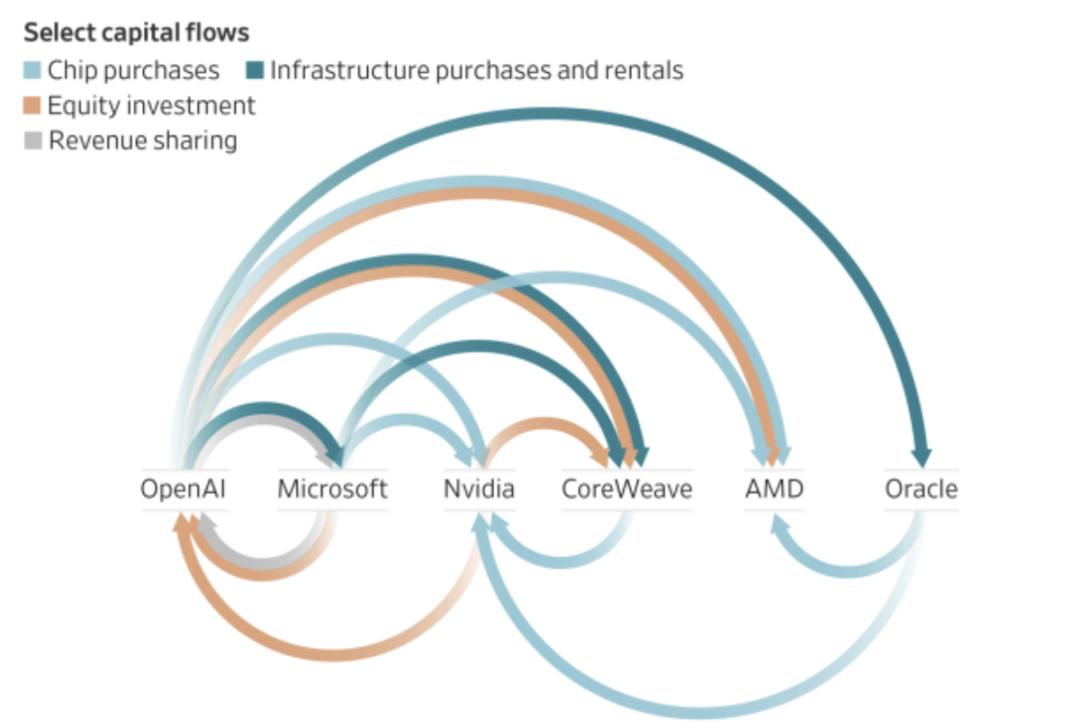

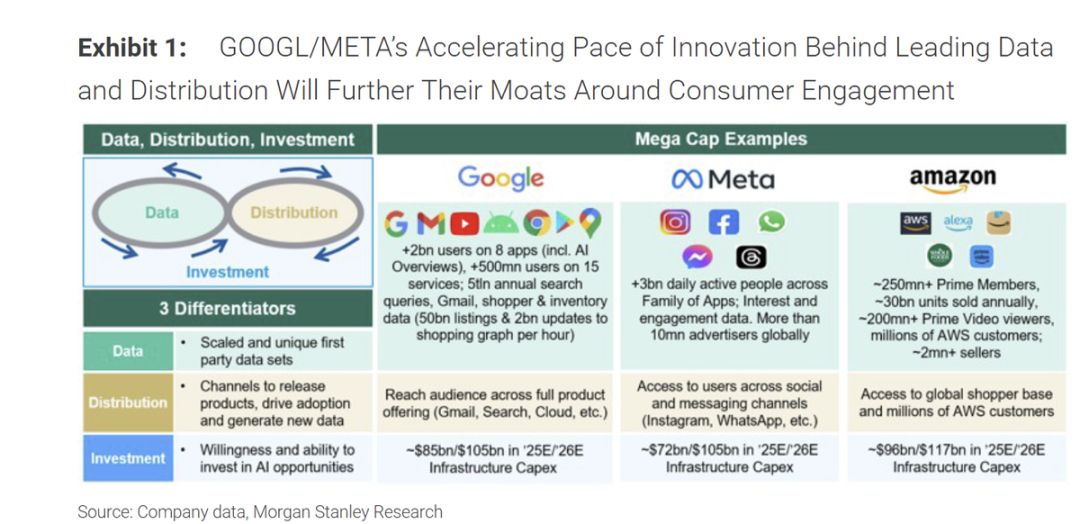

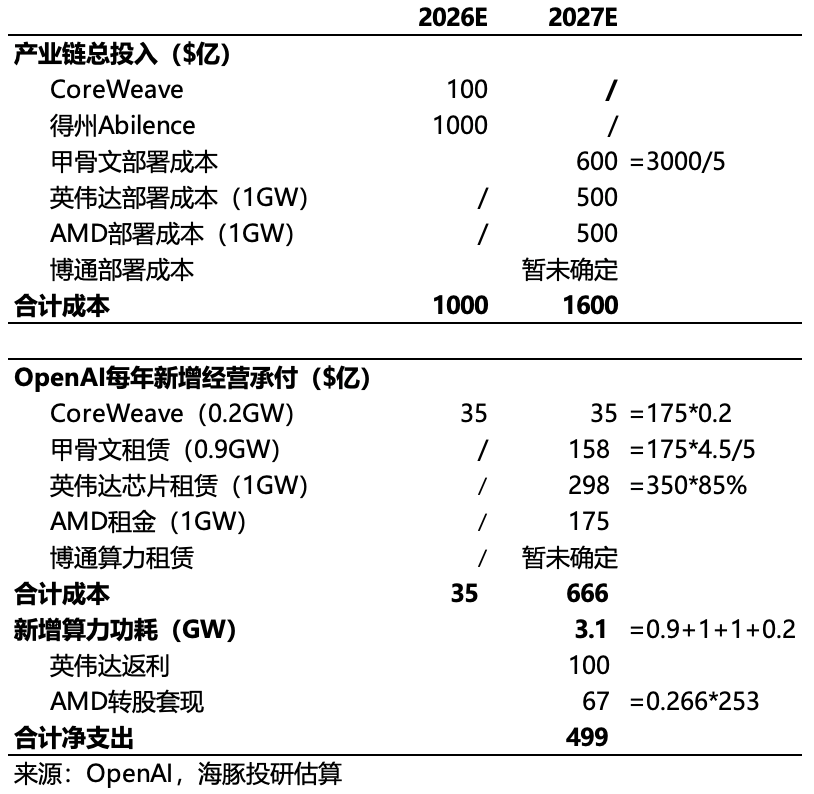

The following chart may already be familiar to many. The biggest issue with this chart is that the end-users of the entire industrial chain, namely OpenAI's users, generate a revenue scale in the overall capital cycle that is too small compared to the investment, and thus are not depicted in the chart.

However, the core message of this chart is essentially that downstream clients use upstream supply chain funds to finance their own businesses—a simple yet ancient supply chain financing method.

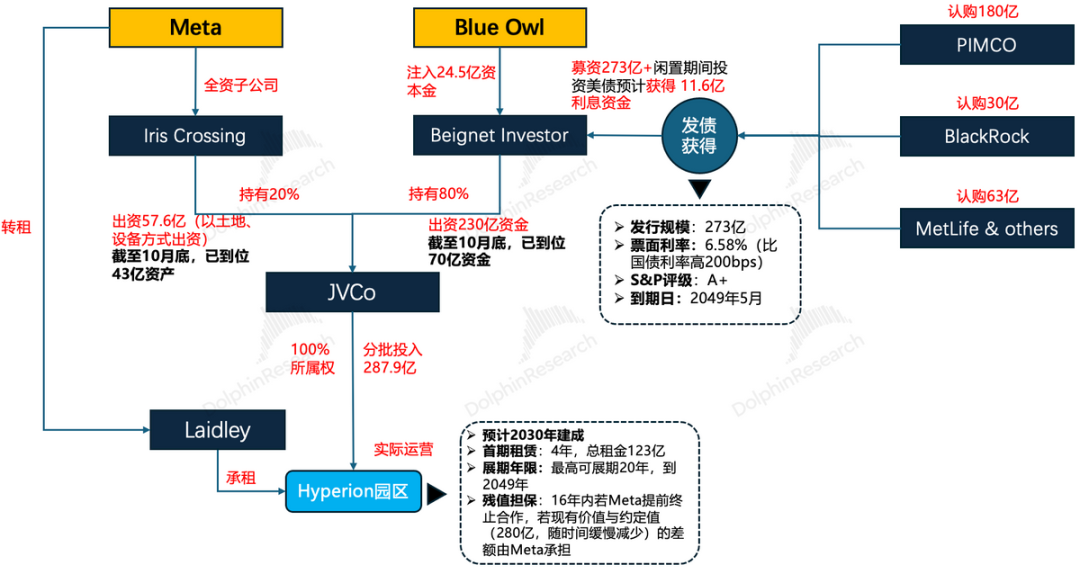

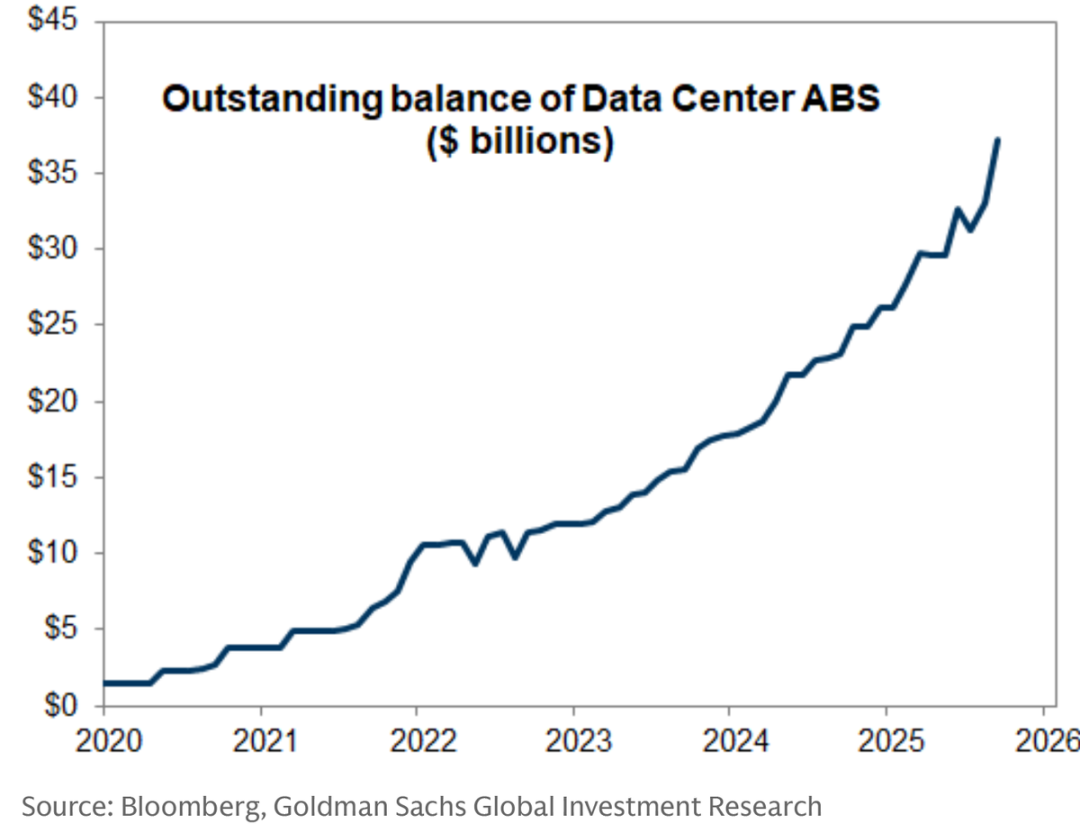

Meanwhile, as primary market model giants engage in supply chain financing, secondary market application giants have gradually and widely adopted on-balance-sheet and off-balance-sheet bond financing (a detailed analysis can be found here).

However, the question remains: why, when chipmakers like NVIDIA are reaping huge profits and the entire market is proclaiming AI as the next technological revolution, does AI pioneer OpenAI need to engage in such a massive financing scheme? Why do once-wealthy U.S. stock giants like Google and Meta now rely on debt to sustain their future development?

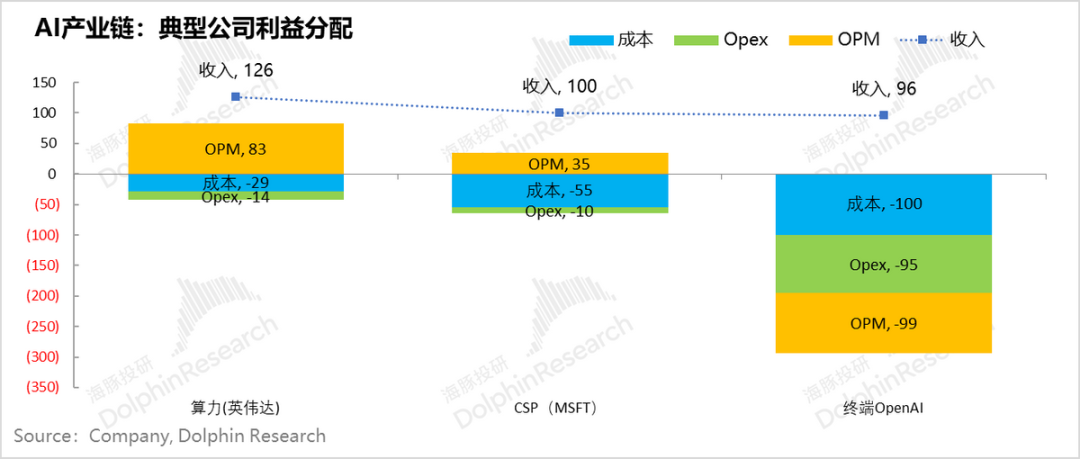

The answer is simple: in the early stages of the AI industry, profit distribution along the industrial chain is severely uneven, with the upstream essentially 'cleaning up.'

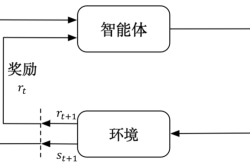

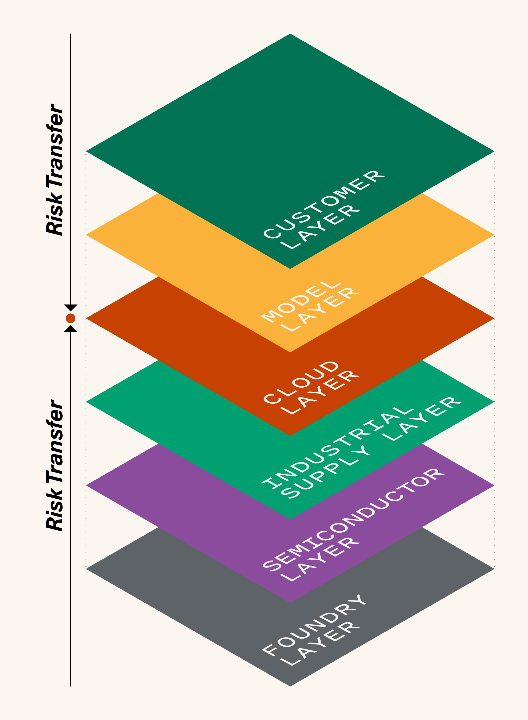

The main AI industrial chain primarily consists of five types of players: wafer foundries (TSMC) – computing power providers (NVIDIA) – cloud service providers (Microsoft) – model developers (OpenAI) – and end-user scenarios, divided into five layers.

1.1) Starting with the Economics of Cloud Service Providers: Who Reaps the Profits, Who Gets the Hype, and Who Bears the Risks?

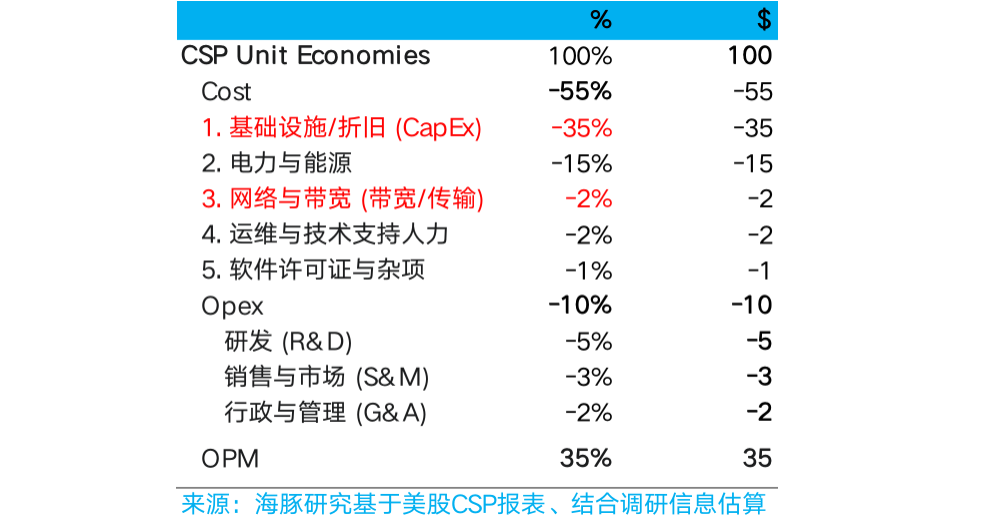

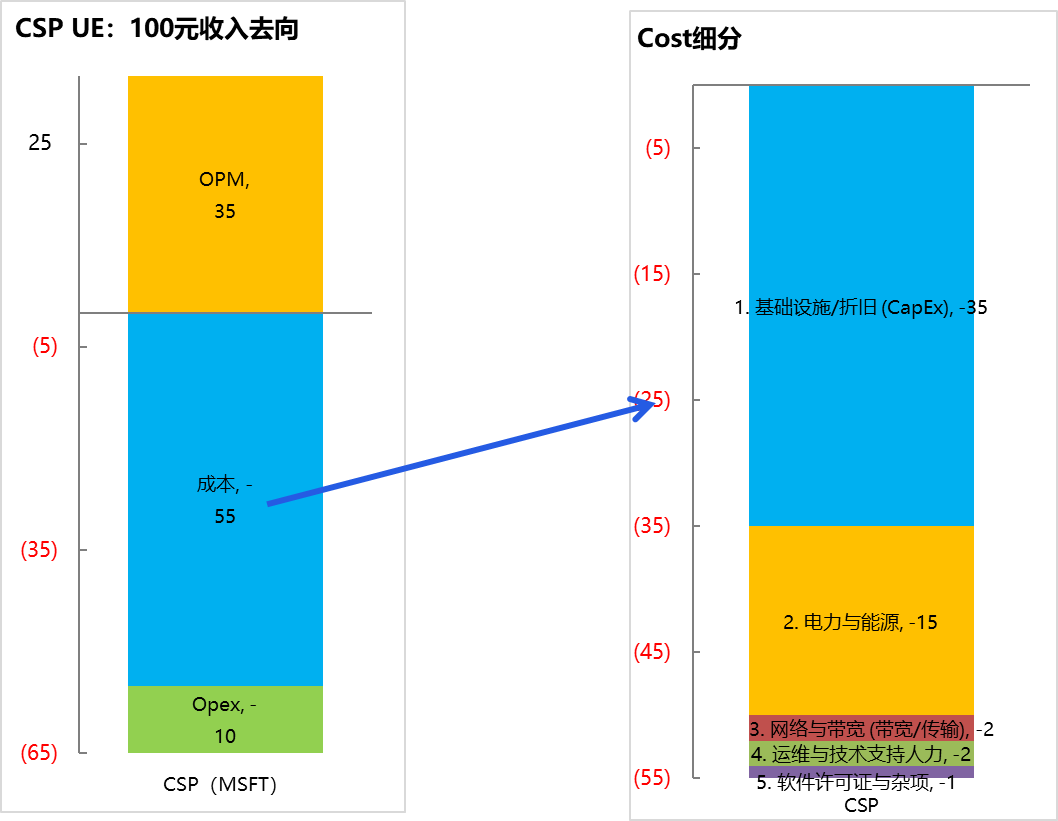

A. The Economics of Cloud Service Providers: For every 100 yuan in revenue – 55 yuan in costs, 10 yuan in operating expenses, and 35 yuan in profit;

Below, Dolphin Research uses a simple economic analysis of the industrial chain to provide a clear picture of the three-year AI boom. We know that cloud services are an industry with both high capital barriers and high technical barriers. The initial phase resembles construction—building the facility, installing cabinets, cabling, cooling, etc.—this is the 'hard' part of the data center.

The 'soft' part involves installing GPUs and CPUs, ensuring proper internal GPU connections, GPU-to-GPU connections, and connections with other devices, along with networking, bandwidth, and power. Once these elements are in place and technical personnel (technical personnel) complete the 'finishing touches,' a basic IaaS service is born.

From the above, it is clear that while cloud services sound high-tech, they essentially fall within the realm of operator businesses—combining heavy assets with technology to form cloud services and earning money through leasing them.

The core of this business is to keep costs low. For example, the most expensive GPUs, once installed, should last for a decade or more, unlike solar farms where panels need frequent replacement.

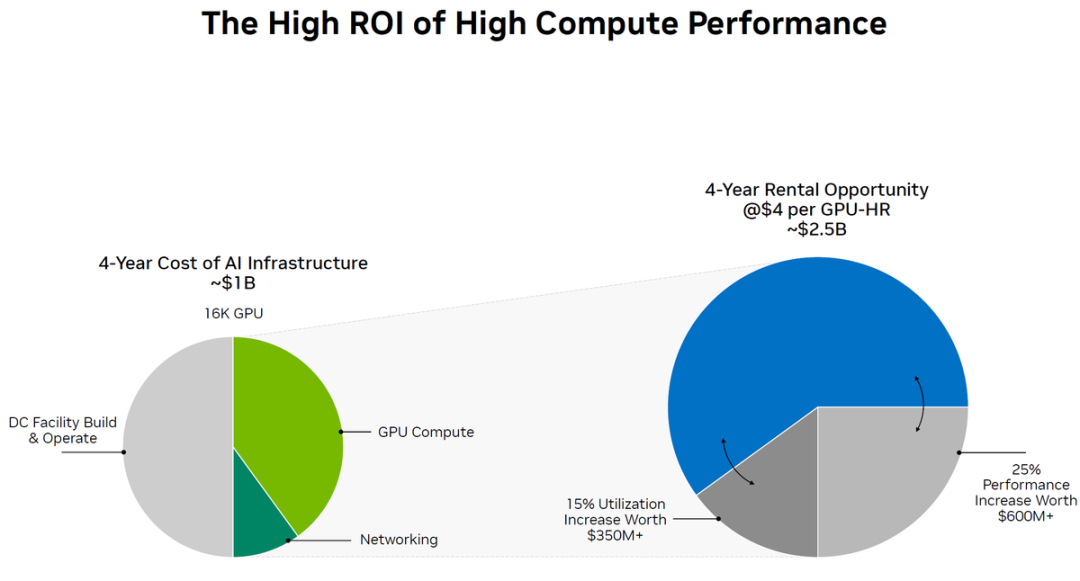

Source: NVIDIA NDR Materials

According to Dolphin Research's estimates, if cloud service providers use entirely new AI capacity to offer AI cloud services, for every 100 yuan earned, approximately 35 yuan goes toward amortizing the initial equipment (primarily GPUs) purchase. With GPU depreciation typically calculated over a five-year period by cloud service providers, the actual capital expenditure is 175 yuan.

If NVIDIA supplies the GPUs, then roughly 125 yuan (over 70%) comes from GPU (including networking equipment) revenue, with the remainder from CPUs, storage, networking equipment, etc.

Beyond fixed costs, there are expenses for energy, electricity, bandwidth, and operations. Operating expenses mainly cover R&D, sales, and administrative costs. Ultimately, the book operating profit from 100 yuan in revenue is 35 yuan.

Note: Data is based on an estimated profit margin between AWS and Azure, combined with a simulation comparing the ROI of GPU cloud leasing with traditional methods.

From these numbers, a clear issue emerges:

① In the early stages of AI infrastructure, cloud service providers only have paper profits but are severely cash-strapped: In this simple model, cloud service providers appear to earn 35 yuan, but in reality, their entire 100 yuan in revenue is insufficient to cover the 175 yuan needed upfront for GPU equipment. In other words, CSPs only earn paper profits while their actual investments are in the red.

② Data centers are frantically seeking financing: Previously supported by cash cow businesses, major cloud providers now face a new reality. Emerging cloud players like CoreWeave, Nebius, Crusoe, Together, Lambda, Firmus, and Nscale, lacking established cash flow businesses, now widely rely on asset-backed securities for financing to provide cloud services.

B. How Does 100 Yuan in Cloud Service Revenue Flow into NVIDIA and OpenAI's Books?

① Computing Power Provider (NVIDIA) – A Profitable Equipment Stock

The cost for cloud service providers becomes revenue for NVIDIA. For every 100 yuan in cloud service revenue, 35 yuan goes toward equipment depreciation. Over a five-year depreciation period, approximately 175 yuan in equipment must be procured upfront to provide these services.

NVIDIA's GPUs account for roughly 70% of the procurement value, meaning that for every 100 yuan in cloud service revenue, 125 yuan is already spent on GPU equipment purchases from NVIDIA.

Clearly, as the highest-value single component in cloud service providers' procurement of production materials, NVIDIA has reaped enormous profits in the early stages of AI infrastructure development.

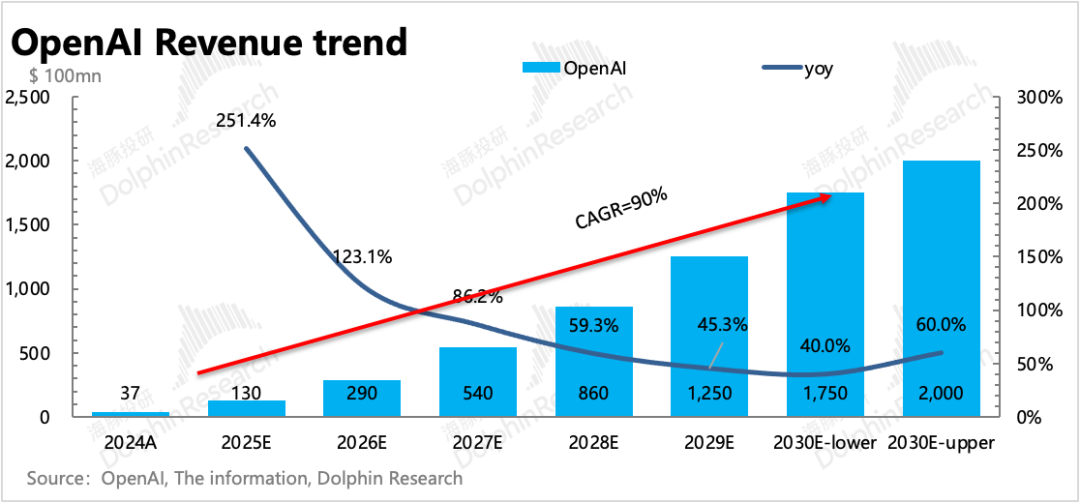

② Current State of OpenAI – 800 Million WAU, But Bleeding Money

Within the entire industrial chain, OpenAI—the demand side of cloud services—is the source of demand. Its solvency determines the health of this chain's cycle. However, based on OAI's current revenue-generating capacity, despite investing heavily in computing power resources, the results can only be described as using a 'golden shovel' to dig for 'dirt.'

First, the 100 yuan in GPU leasing revenue earned by cloud service providers becomes the cloud service cost for OpenAI when providing services to its users. According to OpenAI's financial status for the first half of 2025 as disclosed by the media, 100 yuan in cloud expenses corresponds to only 96 yuan in company revenue. When factoring in R&D personnel expenses, marketing, and administrative costs (excluding stock-based compensation)—another 100 yuan in expenses—the company essentially loses 100 yuan.

C. Core Conflict: Severe Distortion in Industrial Chain Profit Distribution

When we combine the simplified economic analyses of these three companies, a stark picture of industrial chain profit distribution emerges: an extremely uneven allocation of profits, risks, and rewards among the core players in the industrial chain.

Upstream 'Shovel' Stocks – Represented by NVIDIA, computing power assets are light-asset businesses that, leveraging their monopoly position, enjoy rapid revenue growth, low accounts receivable risks, and high-profit quality, reaping enormous profits;

Midstream Resource Integrators – Cloud service providers shoulder substantial industrial chain investments and resource integration, with massive upfront investments. While they appear profitable on paper, they are severely cash-strapped and are, in fact, the largest risk bearers;

Downstream Application Providers – The cost of production materials (cloud services) is too high, while revenue is too low, barely covering a portion of cloud service costs. These application stocks are clearly losing money, and their health ultimately determines the viability of the entire industrial chain.

As profits continue to shift upstream in this industrial chain, contradictions among the main players in the AI industrial chain intensify, and the dynamic balance of industry competition begins to shift significantly:

① Computing Power – NVIDIA

NVIDIA, leveraging its monopoly on third-party GPUs, particularly its unique advantages in the training phase, has enjoyed the greatest benefits in the early stages of AI infrastructure development. However, its products are not consumables but capital goods that can be used for many years.

Its high growth, from an industry beta perspective, is primarily concentrated during the capacity expansion phase of AI data centers. The company's growth trajectory is highly dependent on the capital expenditure growth rate of cloud service providers. Once cloud providers' capital spending stabilizes at new highs and ceases to grow rapidly, corresponding chipmaker revenue will stagnate. Any miscalculation of the cycle, coupled with inventory write-downs, could cause profit margins to plummet.

In the latest quarter, NVIDIA's top four customers contributed 61% of its revenue, clearly indicating that its income is tied to the capital expenditure budgets of cloud service providers.

Source: NVIDIA 2025 NDR Materials

Under the pressure of maintaining a $4-5 trillion market cap, NVIDIA faces immense pressure to continuously deliver chips and prop up half of the U.S. stock market. Thus, its core objective is to keep selling chips—and more of them—through methods such as:

a. Expanding chip sales overseas, such as Trump leading GPU manufacturers to sign deals in the Middle East; while simultaneously losing the Chinese market, prompting Jensen Huang to warn that the U.S. could lose the AI war.

b. Rapid iteration: Creating a constant need for cloud service providers to upgrade their equipment. NVIDIA typically introduces a major product series update every 2-3 years, with some versions requiring entirely new data center construction standards to accommodate GPUs.

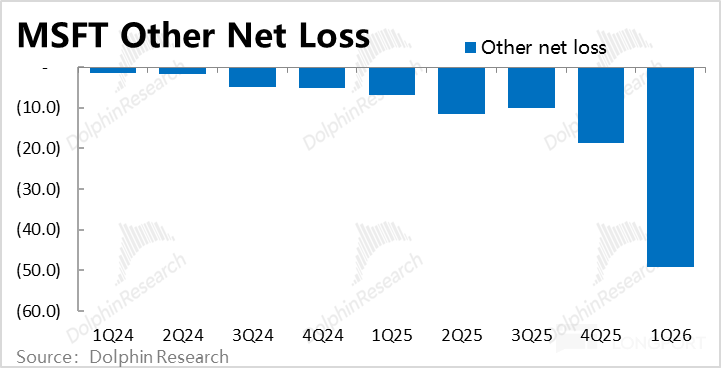

② Cloud Service Providers – Microsoft: Vertical Integration to Reduce Costs

Cloud service providers currently face supply shortages and seem to enjoy industry dividends, but in the long run, they bear the risk of capacity misallocation since they shoulder the majority of capital expenditures. Any misjudgment in demand could leave data centers idle, making them the most vulnerable link in the industrial chain. Specifically,

a. Short-term: Lower Gross Margins for Cloud Services

The immediate issue is that GPUs are too expensive, resulting in lower gross margins for GPU cloud services compared to traditional cloud services. According to Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, profits in the current AI cloud business come not from GPUs but from the deployment of other equipment (storage, networking, bandwidth, etc.)—in other words, today's AI data centers use GPUs as a draw, relying on bundled additional products to generate revenue.

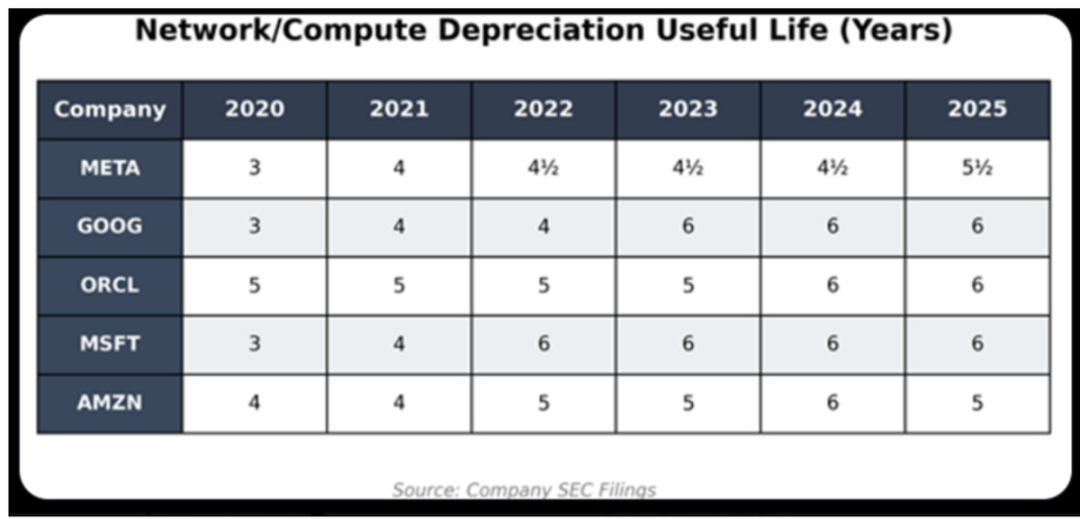

b. Amortization and Depreciation Risks of AI Computing Power

Operator businesses are capital-intensive, and the greatest fear is a too-short amortization and depreciation cycle for production material investments (similar issues have plagued wind farms and 3G-era telecom operators). NVIDIA's rapid product iteration (every two years) makes depreciation periods critical;

c. Risks of Pre-positioning Investment

Long-term resource integration and financial risks (capital expenditures) have been assumed; if customer profitability is insufficient, scene implementation is slow, or there is a sudden nonlinear iteration in technology (e.g., models becoming lighter, small models capable of completing large AI tasks on edge devices, or software iterations significantly reducing computational power demands), there may be insufficient utilization of subsequent production capacity. This could lead to misjudgments in production capacity and demand by cloud service providers, making them the primary risk bearers for the failure of major downstream customers. This risk manifests not as uncollectible accounts receivable but as wasted production capacity in data centers.

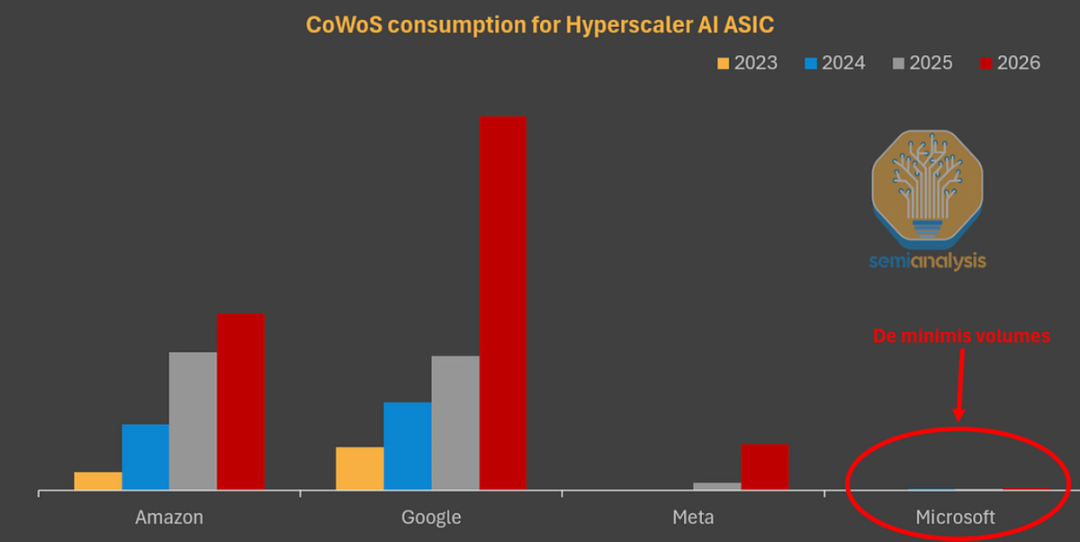

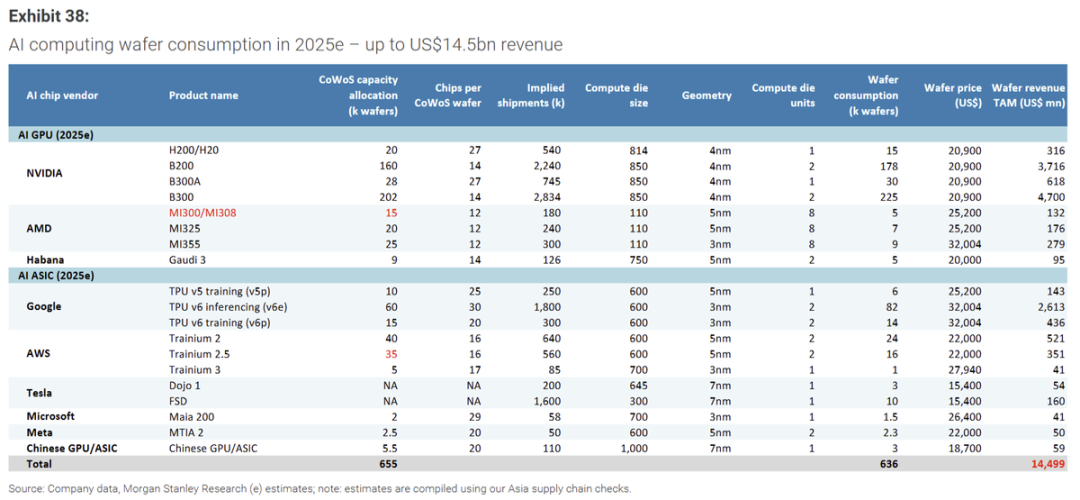

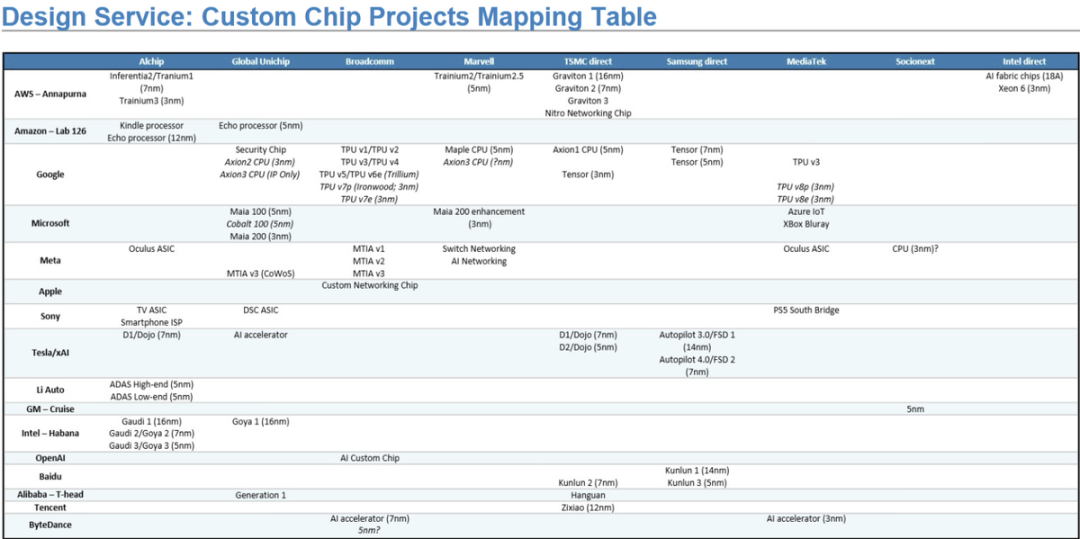

From the perspective of cloud service providers, a viable approach is to reduce the maximum cost item in data centers—GPU costs—such as bypassing the 'NVIDIA tax' by developing in-house 1P computing power chips. Although some design work may need to be outsourced to ASIC designers like Broadcom and Marvell, overall costs can be significantly reduced. Based on available data, constructing a 1GW computing power center using NVIDIA GPUs costs $50 billion, whereas using TPUs costs approximately $20-30 billion.

③ Major Risks in Downstream Applications (Including Models) – High Production Material Costs, Mismatched Revenues, and Cash Flow Disruption Risks

Here, OpenAI is selected as a representative of terminal scene application stocks (including the model layer).

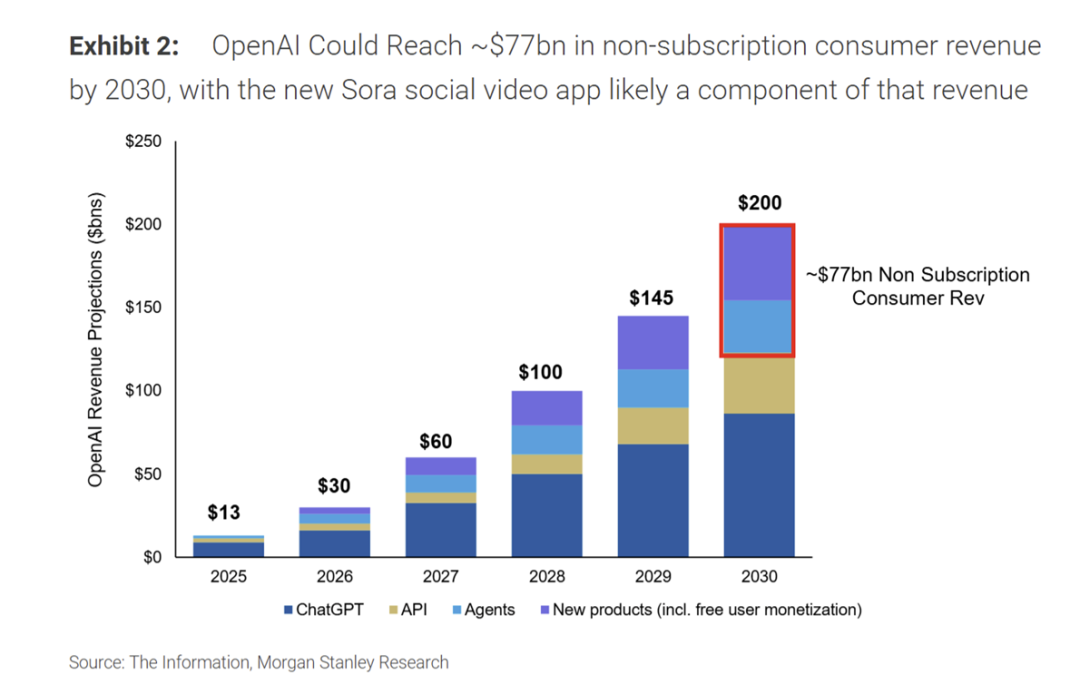

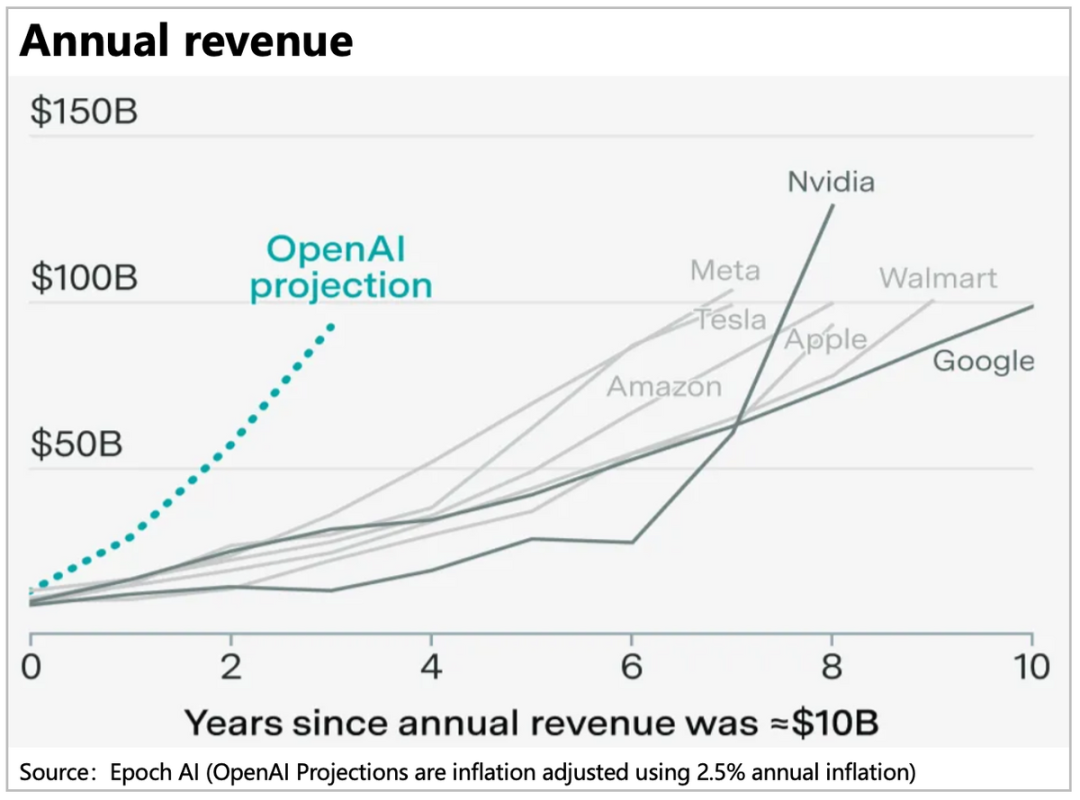

Rapid Revenue Growth: According to media reports, based on OpenAI's current monthly revenue growth rate, it is projected to reach an annualized revenue of $20 billion by the end of 2025, with a full-year revenue of $13 billion in 2025, representing a year-over-year increase of 250%.

Expenditure Soaring Even Faster: The issue here is that during periods of rapid revenue growth, there is no gradual reduction in the loss rate as revenue increases, as would typically occur in a normal business model. Instead, the growth rate of expenditures exceeds that of revenues, resulting in higher losses as revenues increase.

According to media reports, with a revenue of $13 billion in 2025, losses are estimated to be at least $15 billion. Based on Microsoft's financial report information (assuming a 40% stake), OpenAI's annualized losses are projected to exceed $30 billion.

OpenAI's current demands are evident. Firstly, cloud service costs are excessively high, leading to uneconomical revenues—the more revenue generated, the greater the losses. Secondly, due to the significant revenue gap, the company requires financing while also needing to further increase revenues. However, during this process, reliance on external cloud services leads to supplier capacity constraints, causing delays in product launches (e.g., Sora's delay and the high pricing of OpenAI Pulse dragging down penetration rates).

III. AI Industry Chain: Competition for Pricing Power Among Giants

AI technology (models) is iterating rapidly and gradually maturing to a deployable stage. However, deployment costs are excessively high—cloud service costs are prohibitive, preventing rapid expansion of technology in application scenarios.

The aforementioned economic simulations clearly reveal that high costs are attributable to severe markup in the industry chain—NVIDIA chips have a gross margin of 75% (a 4x markup), while CSPs (cloud services) have a gross margin of around 50% (a 2x markup). By the time OpenAI utilizes these resources, the cost of 'shovels' has become excessively high. Even applications with relatively steep growth trajectories in internet history cannot cover the even faster-rising costs.

Thus, competition within the industry chain has commenced!

NVIDIA, leveraging its high value and technological barriers in data centers, aims to deplete the value of cloud service providers, reducing them to mere contractors for GPUs. In contrast, cloud service providers view NVIDIA's 'taxation' as exorbitant and seek to eliminate NVIDIA's excess profits through in-house chip development.

Since Microsoft lifted the restriction requiring OpenAI to exclusively use Azure as its cloud service provider, OpenAI has explicitly expressed its intention to build its own data centers. OpenAI seems determined to eliminate excess premiums at every stage of the upstream supply chain, ideally driving computing power prices down to commodity levels and fostering application prosperity.

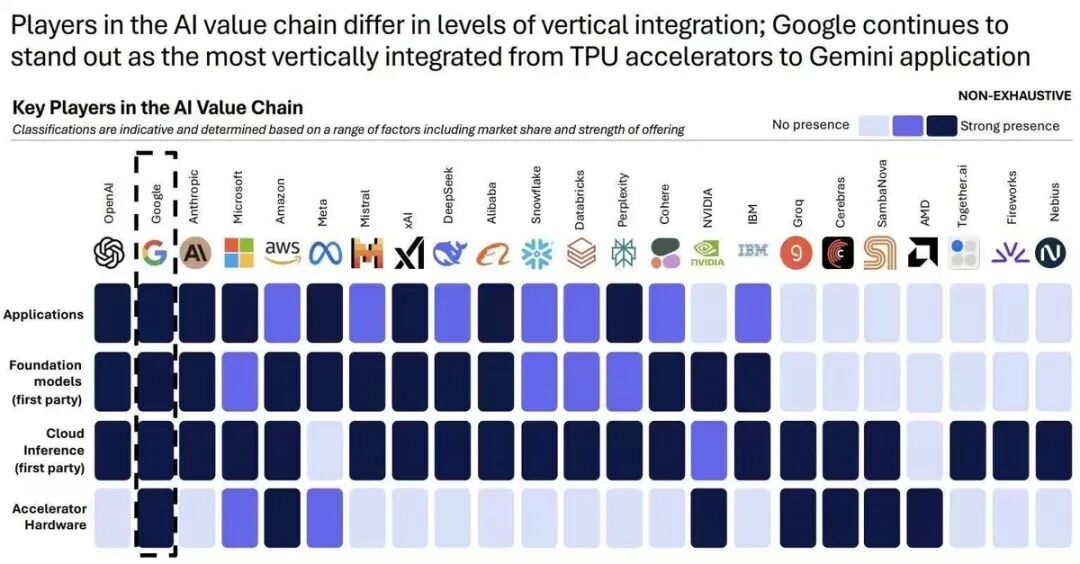

Consequently, the most favored business model by the end of 2025 and the current most popular investment trend, 'full-stack AI,' essentially represents vertical integration of the industry chain. Although the three major players operate differently, they are all striving towards vertical integration:

① NVIDIA: NVIDIA + Emerging Cloud Players = Weakening the Industrial Position of Major CSPs

Relying on its monopoly in GPUs, NVIDIA supports a host of emerging cloud platforms (e.g., Coreweave, Nebius) that depend on NVIDIA for supply prioritization by offering priority access to the latest Rack systems and capacity repurchase agreements. Notably, NVIDIA's repurchase guarantee for Coreweave stands out.

These new cloud players, which have generally secured substantial financing, mostly rely on NVIDIA's supply tilt (supply prioritization) or financial support, ultimately utilizing NVIDIA chips for their capacity. Through this strategy, NVIDIA effectively restricts GPU options for other small cloud service providers besides major CSPs.

However, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella indirectly expressed in an interview that 'some people believe providing cloud services simply involves buying a bunch of servers and plugging them in.' Implicitly, cloud services are a highly complex business with significant barriers to entry. Otherwise, the global cloud service market, despite its vast size, would not be dominated by just a few players.

From this perspective, the newly hyped cloud service providers this year are, to some extent, downstream agents (resellers) elevated by NVIDIA's supply prioritization amid GPU shortages. If long-term industry supply and demand balance out and competition logics shift towards normal technology, capital, channel, and scale-oriented business models, the survival of these new cloud players remains uncertain.

It seems that AI new cloud players are more akin to transitional products in the industry chain competition during the first half of the AI infrastructure boom, rather than competitors capable of rivaling cloud service giants in a balanced supply-demand endgame.

② Cloud Service Providers: Cloud Service Providers + ASIC Designers + Downstream Products = Weakening NVIDIA's Chip Monopoly Premium

a. Currently, companies with significant GPU usage have largely embarked on in-house chip development efforts. Besides cloud service providers, major downstream customers with substantial usage, such as Meta, ByteDance, and Tesla, are also developing ASIC chips.

In the ASIC chip self-development sub-chain, ASIC design outsourcing providers like Broadcom, Marvell, AIchip, AUC, and MediaTek are high-value assets.

b. The Bargaining Power of Secondary Suppliers as Alternatives

The earliest and most renowned self-developed chip is Google's TPU, developed in collaboration with Broadcom, which directly supplies Gemini 3's development. Meanwhile, Amazon also initiated self-developed GPU research early on (Trainium for training and Inferentia for inference).

According to NVIDIA's financial report (Anthropic's first use of NVIDIA collaboration), Anthropic's model development primarily relies on Amazon's cloud and Trainium chips.

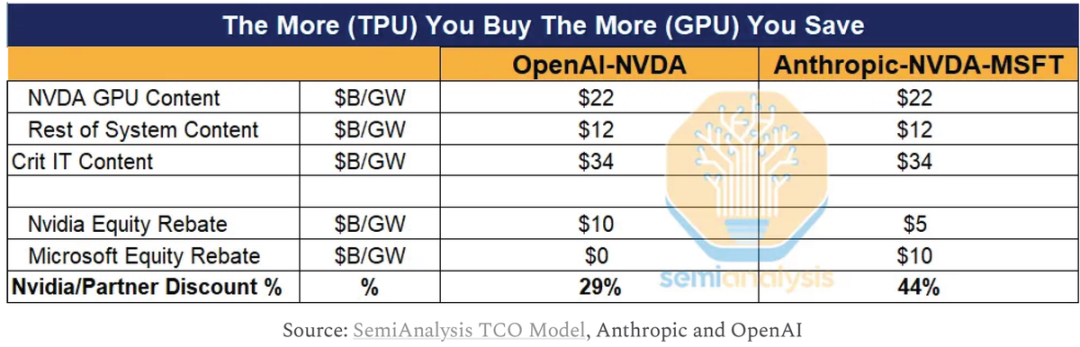

The two leading models globally, Gemini and Anthropic, have achieved leading positions in model training without significant reliance on NVIDIA (Gemini uses none, while Anthropic uses minimal amounts), clearly impacting NVIDIA's pricing power in the computing industry.

Under the influence of such cases, downstream customers can force NVIDIA to indirectly lower prices by threatening to use TPUs (even without actual deployment), thereby locking in downstream customer orders through financing guarantees, equity financing, and residual capacity guarantees. Essentially, customers have driven down the cost of deploying GPUs.

These are tangible manifestations of NVIDIA's computing power status being threatened.

c. Downstream Product Penetration: Fully AI-Equipped Product Lines Defending Against ChatGPT's Rise

These cloud players in the intermediate stage, whose core businesses often extend further downstream into model and software application scenarios, not only prevent NVIDIA from encroaching on their cloud business through vertical integration upwards but also equip their entire product lines with AI to compete with ChatGPT and prevent disruption.

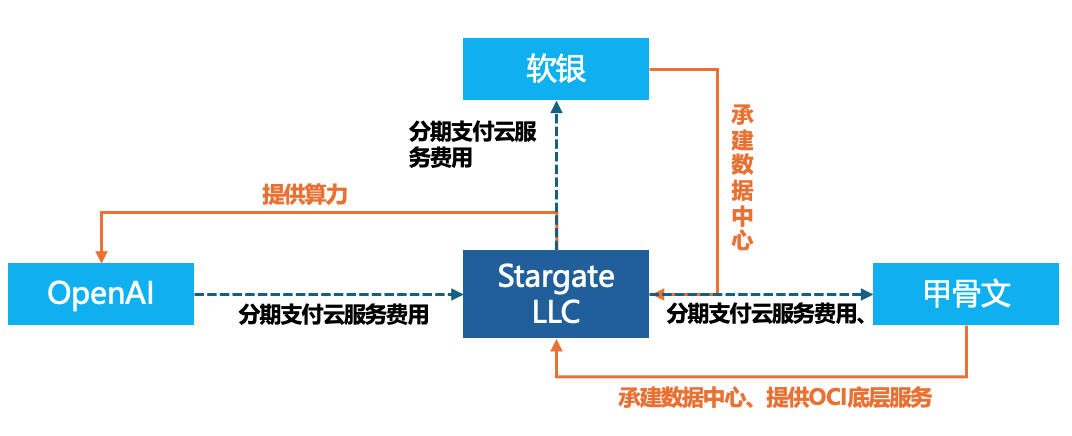

③ OpenAI: Industry Chain Autonomy = Stargate

As a new company operating in the model factory and application scenario space, OpenAI, under substantial losses, seeks to avoid being constrained by giants and leverage its influence to build a largely autonomous industry chain through financing. OpenAI's broad vision includes a 50-50 split between self-developed and externally sourced upstream computing power (AMD's 6GW as backup capacity), midstream cloud services fully subordinate to its will to maintain technological leadership, and promote AI applications.

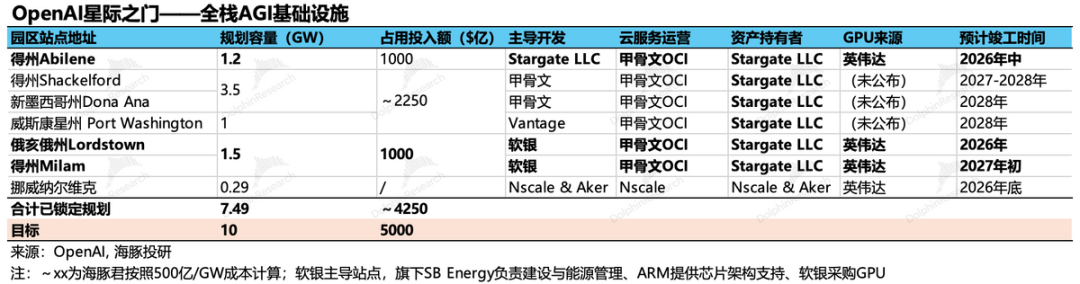

a. Building Data Centers: OpenAI + Financing + Chip Manufacturers + Oracle = Stargate

From the perspective of the company's equity structure design, Stargate is essentially a large-scale emerging cloud company (with a designed capacity of 10GW) dedicated to serving OpenAI's computing power needs. Through initial investment and equity participation, OpenAI holds a 40% stake in Stargate, strengthening its dominance over computing infrastructure.

b. Binding Orders: As a cloud service terminal customer deeply constrained by high computing costs and insufficient supply, OpenAI's best interest lies in abundant and cheap computing power. Leveraging upstream suppliers' FOMO (fear of missing out) psychology, OpenAI binds all available capacity, using future revenue expectations as repayment capability to lock in chip supplies.

However, for OpenAI to genuinely fulfill these payment commitments, its annualized revenue must reach $100 billion within three years from the current $20 billion. No current giant has achieved such revenue growth within a few years. Reasonably, one might infer that OpenAI's intention could be to intentionally create supply overshoots to drive down computing costs.

When asked about the possibility of computing power oversupply, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman openly expressed his desire for it: 'There will definitely be multiple rounds of computing oversupply, whether it occurs within 2-3 years or 5-6 years, probably several times along the way.'

IV. Conclusion: 2026 Investment Theme – Structural Oversupply of Computing Power + Industry Chain Profit Shift?

From the aforementioned analysis, it is evident that the current AI industry chain suffers from excessive profit concentration upstream (similar to the new energy vehicle (NEV) boom, where profits were once highly concentrated in lithium miners like Ganfeng and Tianqi Lithium). This has left downstream players struggling with scene applications akin to digging with golden shovels—the cost of production materials is excessively high, and the value of what is dug up cannot justify these costs.

Therefore, under the current industry chain contradictions, the next AI investment opportunities lie in the shift of industry chain profits and structural supply overshoots. Only by driving down computing costs can downstream prosperity be achieved.

The so-called structural overcapacity, for example, the construction speed of traditional power and computer rooms cannot keep up, leading to idle computing power. Meanwhile, as industrial profits shift downward, key tracking points include the deployment speed of models in end-user scenarios, potential impacts on SaaS stocks, AI penetration in end-side products, and new hardware brought by AI, such as robots and AI glasses.

So far, Dolphin Research has begun to see signs of profit shifting downward in the industrial chain. For instance, NVIDIA's customers can now use TPU as a bargaining chip to demand more favorable supply terms from NVIDIA (in fact, under the same selling price, equity investment is required, which is an indirect form of product price reduction).

Below, Dolphin Research provides several judgments that can be continuously tracked and verified:

a. NVIDIA may have very little chance of enjoying another Davis Double Play in the future. Its stock price can only rely on earnings growth and is unlikely to benefit from valuation expansion. This will suppress the valuation of computing power independently, without affecting TSMC's logic.

b. The news that Google has started selling bare chips instead of higher-margin TPU cloud leasing indicates, on one hand, that Google does not face issues in the production scheduling of its proprietary chips (related to TSMC's capacity arrangement issues).

On the other hand, the real shortage in the industry is expected to shift to the construction of IDC data centers by 2026 (such as issues related to water pollution and power consumption in data center construction). Investments in this area are not barriers to business but rather mismatches in capacity. It is essential to closely monitor the construction pace of newly initiated data centers.

c. Startups: The barrier to entry for AI gaming is too high. Emerging companies like OpenAI face significant challenges in disrupting incumbents. Over-betting on assets linked to the OpenAI chain is unwise.

- END -

// Reprint Authorization

This article is an original piece by Dolphin Research. Reprinting requires authorization.

// Disclaimer and General Disclosure

This report is intended solely for general comprehensive data purposes, designed for users of Dolphin Research and its affiliated entities for general browsing and data reference. It does not take into account the specific investment objectives, investment product preferences, risk tolerance, financial situation, or special needs of any individual receiving this report. Investors must consult with independent professional advisors before making investment decisions based on this report. Any person making investment decisions using or referring to the content or information mentioned in this report assumes full risk. Dolphin Research shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect liabilities or losses that may arise from the use of the data contained in this report. The information and data presented in this report are based on publicly available sources and are provided for reference purposes only. Dolphin Research strives to ensure, but does not guarantee, the reliability, accuracy, and completeness of the relevant information and data.

The information or opinions mentioned in this report shall not, under any jurisdiction, be regarded or construed as an offer to sell securities or an invitation to buy or sell securities, nor shall they constitute advice, inquiries, or recommendations regarding relevant securities or related financial instruments. The information, tools, and materials contained in this report are not intended for, nor are they intended to be distributed to, jurisdictions where the distribution, publication, provision, or use of such information, tools, and materials contradicts applicable laws or regulations, or where it would subject Dolphin Research and/or its subsidiaries or affiliated companies to any registration or licensing requirements in such jurisdictions, nor to citizens or residents of such jurisdictions.

This report solely reflects the personal views, insights, and analytical methods of the relevant contributors and does not represent the stance of Dolphin Research and/or its affiliated entities.

This report is produced by Dolphin Research, and its copyright is solely owned by Dolphin Research. Without the prior written consent of Dolphin Research, no institution or individual may (i) produce, copy, duplicate, reproduce, forward, or distribute in any form whatsoever, copies or replicas, and/or (ii) directly or indirectly redistribute or transfer them to any unauthorized person. Dolphin Research reserves all related rights.