Data Workers: The Unsung Heroes Propelling the Trillion-Dollar Embodied AI Industry

![]() 12/04 2025

12/04 2025

![]() 610

610

As we stand in awe of every deft maneuver executed by robots, it's crucial not to overlook the 'invisible hands' that meticulously chart their paths in the shadows. This isn't merely a matter of business models; it's a profound inquiry into technological ethics and societal values: What kind of humanistic foundation should underpin the intelligent future we aspire to? We're witnessing the ascent of colossal embodied AI structures, yet we must never forget who laid each brick.

Editor: Lv Xinyi

When data becomes the most significant bottleneck in the evolution of embodied AI, preventing it from fully transitioning into the physical realm as its 'soul,' the industry openly debates the merits of real-world data versus other data types, such as simulated and internet data. Real-world data is widely acknowledged as crucial for the development pace of embodied AI due to its superior quality and effectiveness in fine-grained operations. The belief persists that 'massive real-world datasets can dictate the tempo of embodied AI development.'

Yet, few discuss the substantial sacrifices made behind the scenes to gather robot real-world datasets.

This sacrifice is part of a somewhat overused business narrative, akin to how delivery riders hasten to fulfill the instant retail dreams of food delivery platforms. Data collectors play a similar role in embodied AI. By donning operational devices and repeatedly performing simple actions like picking up a water cup, they enable embodied AI to acquire grasping and placing capabilities.

However, due to the immense demand for data and the resulting shortage of data collectors, this task is often outsourced, leading to the creation of more stable embodied AI products amidst unstable working conditions.

Some hail this as an 'era of dividends,' offering a daily wage of 200 yuan without exposure to harsh weather conditions, making it a sought-after part-time gig. Others perceive it as a new profession on par with ride-hailing drivers and delivery riders, suitable for long-term development.

Pessimists, however, see a looming tragedy in this job. 'The work of data collectors is paving the way for Optimus to eventually replace human labor,' commented Business Insider in an article about Tesla's establishment of a data collection team. Through the data collected by these workers, robots become smarter, to the point where what they forge with their own hands may become their future competitors.

Regardless of perspective, this seems to be a new way to earn money in the short term, though the future remains uncertain, and no one holds the prophet's crystal ball. Amidst the industry's noise and restlessness, they resemble a group of 'modern-day gold prospectors,' but this time, they're not mining gold from the earth but extracting data from themselves.

The Pros and Cons of Data Workers

Almost all interviewed data collection practitioners describe this job as a 'tedious physical task.'

Tedium arises from the repetitive nature of the work: employees must wear data collection exoskeletons or remote operation devices, repeating actions such as gripping, picking up, placing, and carrying hundreds of times, akin to teaching a baby to walk as they guide robots to mimic human behavior. The physical aspect is evident in the low technical threshold of the job, with most positions explicitly preferring males and even requiring the ability to lift 15 kilograms.

Inside data collection centers, data collectors walk, grasp, and avoid obstacles in specific scenarios, with every movement precisely recorded to serve as a blueprint for robot behavior. Alternatively, they sit in front of computers, meticulously annotating vast amounts of video frame by frame with labels like 'this is a hand,' 'this is a door handle,' and 'this is a safe behavior.' They act as 'mirrors' and 'mentors' for robots in the digital world.

An interviewee from Business Insider stated bluntly that this job places a significant physical burden, 'almost equivalent to doing aerobic exercise all day.'

Frankly, this type of work shares a highly similar user profile with common part-time jobs like food delivery crowdsourcing, express sorting, and factory general labor, primarily consisting of males in labor-intensive positions with no technical requirements.

However, recruiters often attach 'preference conditions': they hope applicants have backgrounds in computer science, artificial intelligence, or experience in data collection. This job, labeled as 'low-value' and 'to be avoided' on social media, has paradoxically become an internship and employment choice for many computer science and AI junior college students.

These newcomers, mostly with relevant majors and junior college degrees, largely view it as an 'industry dividend.' Xiaolv, a junior college student who previously worked in medical robot data collection and annotation, and Xiaochen, a recent undergraduate in data science, both speak highly of this job. Xiaochen believes that satisfactory compensation, a relatively safe working environment, promising industry prospects, and personal interest drive his positive view. However, like most practitioners, he is aware of the job's instability and plans to accumulate experience as a stepping stone to explore more possibilities in the industry.

This career expectation of 'leapfrogging upward' mirrors the career planning of outsourced AI data annotators and AI trainers aspiring to become AI product managers at large firms. 'Stay close to the cutting-edge sector, accumulate experience from the ground up, and gradually advance,' or 'outstanding performers can become formal employees with social security benefits,' are narrative logics often used by HR to attract job seekers during recruitment.

However, if we expand our view from these 'professionally aligned' labor groups to a broader range of practitioners, we will discover many thought-provoking 'anomalies' among them.

Just as light and shadow coexist, when robots ultimately stand in the spotlight to receive applause, these data workers who taught them everything become invisible shadows.

More eerily, this data labor is undergoing 'alienation.' Much like how programmers have a love-hate relationship with the AI programming tools they create, data workers in labor-intensive positions are teaching their magnificent robots how to perform basic, tedious, and repetitive tasks.

An invisible layer is the sense of 'rootlessness.'

From the internet and mobile computing to large models and now embodied AI, technological trends come and go in waves, and data workers migrate with them, unable to take root. As technology iterates, data labor shifts.

Another aspect of 'drifting with the tide' is reflected in their labor relations. Their work is often obtained through multiple layers of outsourcing, resulting in fragile labor relationships. Once a project terminates, entire teams may disband instantly, with unemployment looming.

In this wave of embodied AI, not to mention comparing with algorithm engineers earning millions annually, the salaries of data workers are no different from other physical labor jobs in recruitment groups. In data collection, for example, in first-tier cities like Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen, the daily wage generally ranges from 160 to 200 yuan, with an hourly wage just over 20 yuan. In data annotation, the price is even lower. This type of work involves target detection and recognition in client videos, labeling them for remote work nationwide. It is currently rapidly developing in third- and fourth-tier cities, driving down labor costs. They represent the most basic and least remunerated link in this high-value-added industrial chain. The low recruitment threshold means high substitutability and weak bargaining power.

Kate Crawford, a renowned political economy critic in the field of artificial intelligence, states in her book 'The Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence,' 'These workers engage in repetitive tasks that support the notion of AI as 'magic,' yet they never receive recognition for keeping the system running smoothly. Despite the critical importance of their work to the 'functioning' of AI systems, they are typically paid very little.'

In simpler terms, when intelligence showcases its breathtaking magic, those behind-the-scenes workers who support its operation do not receive the recognition they deserve, at least not in terms of monetary compensation.

Where Do the Current Conditions of Data Workers Come From?

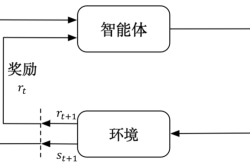

Returning to the origin of the question, where do these 'anomalies' of data workers stem from? The development of AI has spurred the birth of embodied AI, which inherits many of AI's underlying technological logics, one of which is the 'scaling law' of 'more data, better results.' To some extent, the intelligence level of embodied AI is proportional to the quality and quantity of data. The industry even once believed that to understand the complex physical world, embodied AI might need to reach data volumes on par with the 'internet.' Therefore, only by ensuring data is sufficiently clean, precise, and diverse can intelligence emerge from the law of scale.

Thus, embodied AI requires a massive amount of human labor for data collection and annotation to accumulate. These substantial labor costs become burdensome for startups. To 'travel light' amidst the rapid pace of Moore's Law breaking and model iterations, companies choose to outsource this foundational work to third parties.

From a capitalist perspective, this is understandable. The core capital of embodied AI companies must be invested in 'hardcore' areas such as algorithm development and hardware manufacturing. Outsourcing data work is a good way to reduce costs and increase efficiency. However, it must be emphasized that after outsourcing, the management chain lengthens, and the transmission of corporate norms (power) diminishes and becomes ineffective. This easily breeds chaos. Take annotation quality, for example: when an embodied AI company issues an operational manual for data collection or annotation for third-party employees to follow standard operating procedures, there exists a 'secondary qualification' between the 'embodied company-labor service company-third-party employee.' In other words, data originally required to meet standards by 'embodied company-full-time employee' becomes 'passed off' by third-party employees to the labor service company, which in turn 'passes it off' to the embodied AI company, ultimately affecting data quality. (This is the case in some scenarios.)

Returning to the issue of data workers' salaries, after undergoing multiple layers of outsourcing, salaries generally decrease like peeling an onion. You can see on the internet that wages vary among outsourcing parties for this job. A first-hand third party might offer a daily wage of 250 yuan, a second-hand labor service company might offer 200 yuan, and more layers of labor might reduce it to 150 yuan. Ultimately, these workers are treated as resources and passed around repeatedly. Of course, the devaluation of data workers' labor value is also reflected in the fact that the outsourcing project parties themselves may also 'struggle to make ends meet.' The Embodied AI Research Society also interviewed a project manager for a data collection project, who stated, 'Currently, cooperation with manufacturers is quite difficult. Some manufacturers require purchasing their robots to secure business. Now, many prefer to send people over to collect data at the client's site using the client's facilities. However, this essentially turns them into a pure human resources company.' When a company chooses to become a human resources outsourcing firm, it finds itself on the fringes of the embodied industrial chain, naturally unable to claim a significant share of the pie.

In summary, low-quality, poorly motivated data work may even backfire on the technology itself, leading to a decline in data quality. These chaos collectively reveal the 'wild growth' of the industry in its early stages.

Conclusion

As we immerse ourselves in the future blueprint painted by embodied AI, we should not overlook the 'data workers' who support technological iteration. Their career development and industrial evolution are inherently interdependent, not isolated individuals against a backdrop. From the workers' perspective, like Xiaochen, who attempts to 'become a formal manager,' is an ideal path achievable by only a few. More people face the dilemma of 'no skill accumulation, no employment security.' True career growth should revolve around 'experience transformation' and 'risk mitigation.' Bottom-level collectors can leverage their firsthand operational experience to transition into data quality control, such as screening effective action data, correcting redundant annotations, or participating in writing scenario-based collection manuals. They can transform experiences like 'how to enable robots to accurately recognize obstacles' and 'action norms in different scenarios' into industry standards, breaking free from the confines of pure physical labor.

From the industry's perspective, data workers will not indefinitely grow linearly with the construction of data collection factories. Future AI automatic annotation, world model generation, and simulation technology optimization of data collection schemes may gradually 'encroach' on the workers' livelihoods.

However, it is essential to understand that while automation at the 'perceptual' level (such as object recognition) may occur relatively quickly, at the 'cognitive' level requiring an understanding of complex interactions in the physical world (such as force, touch, and emergencies), high-quality human demonstration data will likely remain an irreplaceable 'textbook' for a considerable time.

As we stand in awe of every deft maneuver executed by robots, it's crucial not to overlook the 'invisible hands' that meticulously chart their paths in the shadows. This isn't merely a matter of business models; it's a profound inquiry into technological ethics and societal values: What kind of humanistic foundation should underpin the intelligent future we aspire to? We're witnessing the ascent of colossal embodied AI structures, yet we must never forget who laid each brick.