Revelations from the Bursting of Three Tech Bubbles: How to Escape the 'AI Bubble'?

![]() 12/04 2025

12/04 2025

![]() 667

667

● Nearly every major disruptive innovation has been accompanied by bubbles and busts. Technologies may achieve great success, but behind them lie investors whose assets have vanished.

● The bursting of tech bubbles can be seen as a result of the split between financial capital and production capital.

● The resonance of 'high uncertainty + strong narrative + tradable assets' can trigger a speculative frenzy.

By | Haoran

This article is an original piece by Shangyin Media. For reprints, please contact the background team.

The 'AI Bubble' Debate

In the past two months, concerns over an 'AI bubble' have been growing in the market.

A few days ago, I saw a report that Polymarket, the world's largest prediction platform, had launched bets on 'when the AI bubble will burst.' It listed indicators such as a 50% plunge in Nvidia's stock price, OpenAI or Anthropic declaring bankruptcy or being acquired, and a 40% drop in semiconductor ETFs. As a result, 15% of people believe the AI bubble will burst by March next year, while 40% think it will happen by the end of next year.

This indicates that many people have become more cautious about the prospects of AI, shifting from optimism to prudence.

Concerns about the future of AI are based on a series of signs.

First, the valuations of giants involved in AI have soared too rapidly.

According to CICC data, since ChatGPT ignited the AI wave in 2022, the 'Magnificent Seven' stocks in the U.S. – Microsoft, Nvidia, Amazon, and Google – have surged by up to 283%, far outpacing the 69% gain in the S&P 500 index (excluding these stocks) over the same period.

The same is true in the Chinese market, with notable gains for Alibaba, Tencent, SMIC, Horizon Robotics, and Cambricon.

Second, AI infrastructure is experiencing a 'spending frenzy,' potentially leading to overinvestment.

According to UBS data, AI-related spending is expected to reach $375 billion this year and surpass $500 billion next year. However, current revenues in the AI sector are far from matching such massive investments.

Researchers have found that the capital expenditure-to-revenue ratio in the AI industry is currently 6:1, much higher than during other historical tech bubbles (2:1 for the railroad bubble and 4:1 for the dot-com bubble).

Third, AI companies are engaging in 'circular trading' games.

AI firms are investing in each other, creating internal revenue loops. For example, Nvidia invested $2 billion in xAI, which then borrowed $12.5 billion to purchase Nvidia chips. Microsoft invested $13 billion in OpenAI, which committed to spending $50 billion on Microsoft's cloud services, prompting Microsoft to buy $100 billion worth of Nvidia chips in return.

This 'supplier financing' model blurs the lines between customers, suppliers, and investors, reminiscent of practices seen during the dot-com bubble. For instance, Cisco once funded its customers (telecom operators) to purchase its equipment for large-scale fiber network construction, creating false demand and leading to excess capacity and a subsequent industry collapse.

As a result, many believe the current 'AI bubble' mirrors the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s. Even industry titans like Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates, Google CEO Sundar Pichai, and OpenAI CEO Sam Altman have acknowledged the existence of a bubble, comparing its risks to those of the dot-com era.

So, how should we view the 'AI bubble'?

Revelations from the Bursting of Three Tech Bubbles

Revelations from the Bursting of Three Tech Bubbles

The term 'bubble' is neutral and not inherently bad. Every technological innovation is accompanied by investment and entrepreneurial enthusiasm. These seemingly 'far-fetched' impulses are what drive industrial progress.

However, when more people join in and become overly optimistic about technological innovation, technology transitions from small-scale experimentation to large-scale adoption, often straying from reality. In such cases, an inflating bubble gradually evolves into an unavoidable systemic risk, harboring deep crises.

The key lies in recognizing which stage the bubble has reached and how to identify the risks it harbors.

Mark Twain once said, 'History doesn't repeat itself, but it often rhymes.' This is particularly evident in technological revolutions. Nearly every major disruptive innovation has been accompanied by bubbles and busts. While technologies may achieve great success, behind them lie investors whose assets have vanished.

The steam era saw canal and railroad bubbles.

After Britain's Industrial Revolution in the 18th century, factories and mechanized production emerged, but trains had not yet been invented. During this period, cargo ships handled bulk transportation, leading to a canal-digging frenzy in Britain. Massive funds and labor were poured into canals, causing canal stock prices to soar. This made canal investments high-risk, requiring long operating cycles to recoup costs. However, railroads did not give canals such an opportunity, gradually replacing them and ultimately causing canal stock prices to collapse.

Similar to canal investments, railroads were later hyped as the 'lifeblood' of the new industrial age. Massive funds flooded into Britain's railway industry, with many even investing on leverage. As a result, rail lines were laid everywhere, including in remote areas lacking the commercial capacity to support them. Industry-wide returns dwindled, with revenues amounting to only a quarter of what builders had expected. This, combined with a shift from loose to tight monetary policy, brought the speculative frenzy to an abrupt halt.

In the electrical era, investment booms in aviation, automobiles, and power infrastructure triggered localized crises. Many investors suffered heavy losses during these technological transformations because a technology's journey from inception to widespread adoption involves lengthy exploration of technical routes and business models. Most people struggle to seize opportunities and often fall into traps.

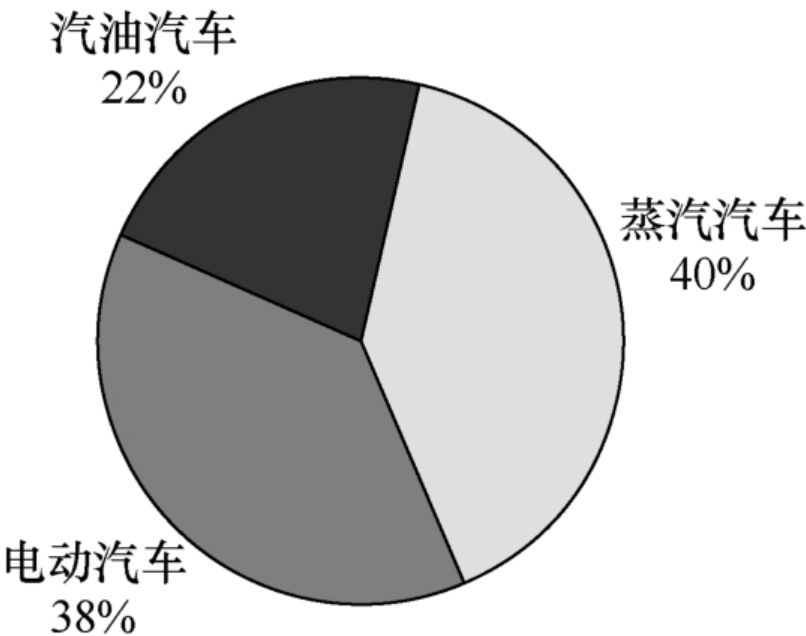

Take the automotive industry as an example. In its early stages, the technical route was uncertain, with three competing power sources: improved steam engines, electric motors, and gasoline engines. While we now know that gasoline-powered cars emerged victorious, steam and electric motors initially dominated the market due to their technical maturity and promising prospects, respectively.

U.S. auto market share in 1900. Source: 'Bubble Escape: A Brief History of Technological Progress and Tech Investments'

Even if you had correctly identified gasoline engines as the winning technology and invested in companies using them, you would still face fierce competition. At its peak, the U.S. had hundreds of auto manufacturers, with more than half failing within six years.

Even if you had accurately identified future winners like General Motors and Ford, you would need to buy in at the right time and sell at the right time. General Motors twice teetered on the brink of bankruptcy in the early 20th century, causing many to give up too soon and miss its eventual turnaround. However, during the Great Depression, auto stocks, including GM's, plummeted again, trapping those who failed to sell in time.

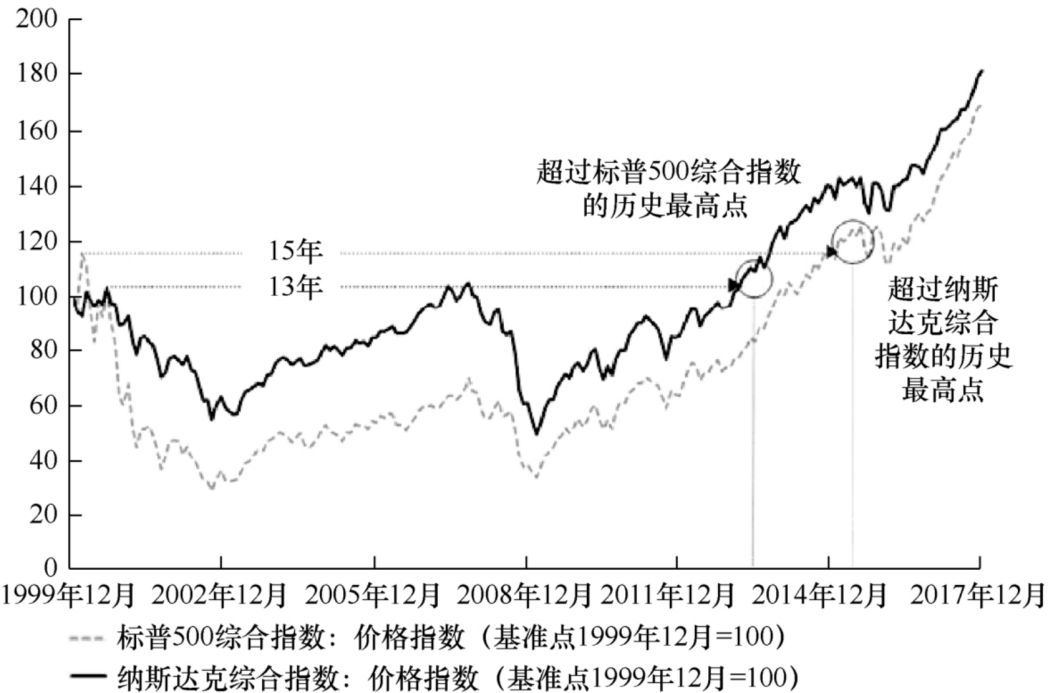

The information age saw an unprecedented bubble that, after bursting in 2000, left most stock markets reeling from losses for over a decade.

Why was the destruction so severe this time?

A key reason is that the dot-com bubble pushed the abandonment of dividends and cash flow as performance metrics to an extreme.

Investors were overly optimistic about the internet's disruptive power, believing it would completely overhaul traditional business models. While the internet did prove disruptive, reliable business models had not yet emerged. Companies like Netscape, which relied on browser license sales, and Yahoo, a portal website, were treated as benchmarks, with their stock prices multiplying several times over.

Traditional valuation methods were discarded, with benchmarks shifting from profitability to revenue, then to metrics like website 'clicks' and future revenue prospects.

As a result, even emerging companies without mature businesses could secure high valuations. A business plan with an 'e-' prefix and a '.com' suffix could fetch tens of millions of dollars in funding.

Of course, extreme optimism about internet technology was only one factor fueling the bubble. Other elements also played a role.

For instance, U.S. interest rates were low at the time, and capital inflows from the Asian financial crisis flooded the market, providing ample liquidity.

Additionally, public psychology played a part. As Robert Shiller noted in 'Irrational Exuberance,' by the late 1990s, the internet had entered households, offering richer entertainment and information than before. This led not only investors but also the general public to become extremely optimistic about the internet. They attributed economic growth, driven by recovery, to this shining new star, believing it to be the engine of new economic growth, despite the lack of profits among internet companies.

Moreover, the U.S. stood alone as a bright spot in the global economy. The Soviet Union had collapsed, Japan's economy was mired in stagnation, and Asia was gripped by a financial crisis. Only the U.S. economy was growing, factors seen as highly favorable for the U.S. stock market. Investing in U.S. stocks became a 'sure bet' for many, much like investing in real estate in previous years.

Internet technology and U.S. stocks thus became the center of attention, sparking a grand expansion. Internet stocks were in high demand, and Wall Street launched a steady stream of IPOs to meet public appetite.

The stock market bubble seemed to burst without warning, rather than through a gradual deflation. On March 10, 2000, the Nasdaq hit its all-time high. Days later, financial reports from major internet companies fell short of expectations, sparking investor panic. A 'Barron's' report titled 'Burn Rate' pointed out that among over 200 internet companies surveyed, 71% were unprofitable, and 51% would run out of cash within a year.

The Federal Reserve also sensed the bubble's magnitude and began raising interest rates. Once high-flying but profit-deficient stars were delisted. The September 11, 2001, attacks dealt another blow to the U.S. stock market. By October 2002, the Nasdaq had plummeted to a quarter of its peak value.

Stages of Bubble Development and Identification

Stages of Bubble Development and Identification

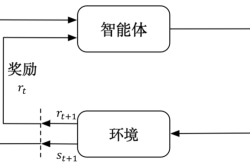

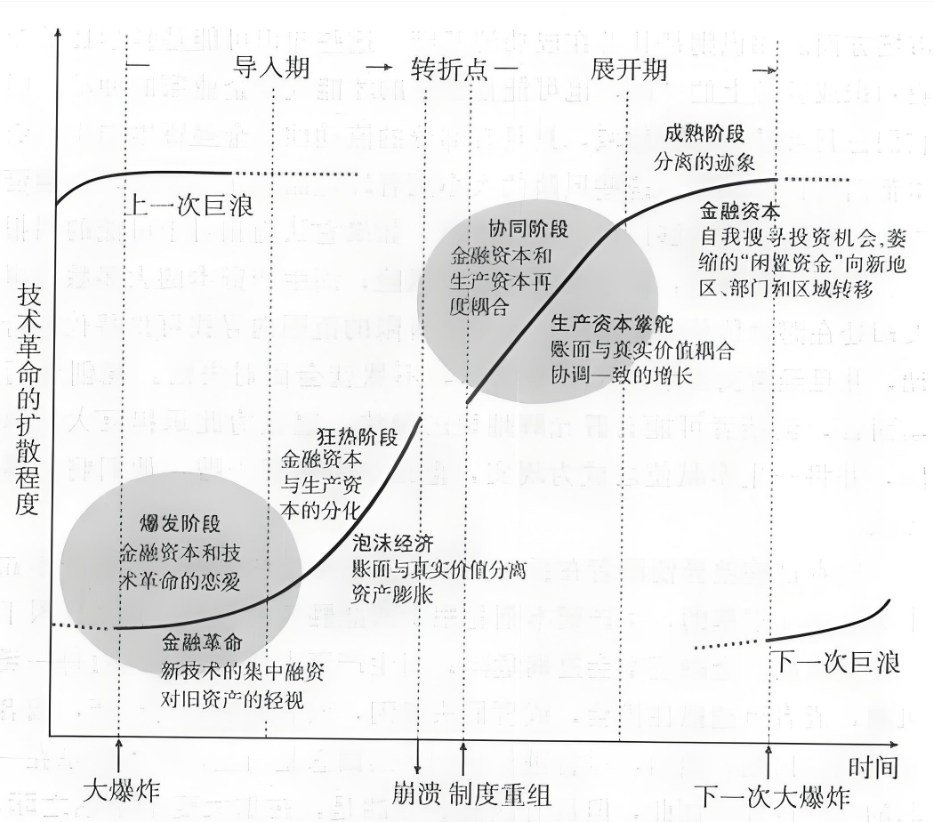

The bursting of tech bubbles can be seen as a result of the split between financial capital and production capital.

Production capital is used to purchase raw materials, equipment, and hire labor, directly participating in commodity production and circulation. Financial capital enters the production sphere indirectly through investments, loans, and securities trading.

Production capital operates in the real economy, requiring investments in machinery, technology R&D, talent recruitment and training, market expansion, and after-sales service. Financial capital, however, operates in the virtual realm, aiming to 'make money from money' by identifying and investing in promising projects. This means production capital yields returns over longer cycles, while financial capital does so more quickly.

From this perspective, it becomes clear that the severity of harm caused by tech bubbles depends on the degree of separation between financial and production capital.

In the electrical era, industries like automobiles and aviation produced only localized bubbles, causing far less damage than the railroad or dot-com bubbles. This is because financial capital did not overly detach from production capital, somewhat resembling today's new energy vehicle industry. Despite competition among dozens of brands and the presence of bubbles, it is largely seen as a manifestation of internal competition and overcapacity.

In contrast, the railroad and dot-com bubbles entered a stage of severe detachment from cash flow, dominated by financial capital. Financial capital believed it could create wealth through its own actions, treating production capital as mere fodder for manipulation and speculation. This led to a growing mismatch between book wealth and real wealth, as well as between genuine profits or dividends and capital gains. Ultimately, the bubbles collapsed in a crisis.

British economist Carlota Perez, in her book 'Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital,' explains the relationship between financial and production capital at different stages. The stage of severe divergence is when bubbles burst, marking the most destructive period of tech transformations. However, it is also when new technologies leverage abundant funding for crazy trial-and-error, laying new infrastructure, and popularizing new technologies and industries through short-term wealth creation, making their use a 'common sense.'

The post-bubble collaboration stage, where financial and production capital collaborate, is the 'golden age' for technology to truly transform industries. Financial capital returns to reality, constrained by new rules and institutions, and begins serving production capital again. Most industries start widely adopting new technologies, with production capital regaining control and creating genuine growth and dividends.

This has also been proven in reality. During the 'Railway Bubble', stock prices were pushed up by high expectations around 1850 and collapsed due to panic in 1857. However, the real production dividends only became apparent in the early 1860s after the completion of the national railway network.

Similarly, after the burst of the Internet bubble, the real dividends only truly materialized in the first decade of the 21st century, as it began to transform industries across the board.

Therefore, financial capital plays the role of pre-digesting uncertainty, while productive capital requires time to build infrastructure and transform organizational forms. Ultimately, wealth growth still relies on real output.

From the perspective of the relationship between financial capital and productive capital, the current development of AI seems to still be some distance away from the stage of frenzy. For example, AI giants rely more on endogenous cash flows, i.e., productive capital, with limited dependence on financial capital, and have achieved substantial and continuously growing revenues. Currently, the dynamic price-to-earnings ratios of the 'Magnificent Seven' stocks are around 30 times, whereas during the Internet bubble, they were commonly at 50 or 60 times.

Additionally, although AI technology continues to upgrade, its disruptive impact has not yet been significantly evident in the daily lives of the general public. AI large language models often make mistakes, humanoid robots are widely ridiculed, and AI's optimization of algorithms has not been particularly impressive.

This has not yet formed an 'irrational consensus' at the mass level, similar to that during the Internet bubble. At that time, people were leaving behind the industrial age and facing a new information-based world, with a lower threshold for perceiving technological changes, making it easier to feel a strong contrast, compounded by special international situations and psychological states.

However, its non-arrival does not mean it will not happen. From historical experience, disruptive innovations almost inevitably come with bubble bursts, varying only in scale. How can we avoid the harms caused by bubbles?

The book 'Bubbles and Crashes: Boom and Bust in Technological Innovation' mentions a key rule: technology itself does not create bubbles; it is only when 'high uncertainty + strong narrative + tradable vehicle' resonate together that a speculative frenzy is ignited.

Uncertainty Dimension

Uncertainty primarily involves the technological route, market competition, business models and value chains, as well as market demand. The more uncertainties there are among these factors, the greater the likelihood of sharp rises and falls. Conversely, if these become clear, the likelihood of bubbles will diminish.

Narrative Dimension

'Before a company truly takes off, it is essentially just a story about an 'imagined future.'' This means that behind every 'technological narrative' lies people's various expectations and speculations about the future—essentially, their 'bets' on future trends.

The strength of a 'technological narrative' depends, firstly, on the imagination space. The more future scenarios a technology can support in people's imaginations, the more easily it will attract widespread pursuit.

For example, during the railway bubble, railways were not only the arteries for transporting bulk goods but also related to urban expansion. If extended to everyone's doorstep, they would facilitate daily travel and greatly benefit the upgrading of international trade, thus attracting more investment. The Internet initially also created a beautiful vision for transforming various aspects of daily life, attracting people from different social strata to invest in the future.

Secondly, it depends on the duration until verification. The longer a narrative takes to be verified, the greater the likelihood of a bubble. Canals, railways, electricity, the Internet, and AI all require a long time to lay down infrastructure, during which a great deal of speculation can arise.

Finally, there is the threshold for understanding the narrative. Technologies are generally complex, but if a complex technology is explained in a way that is extremely relatable to ordinary life and the investment threshold is low, it will have greater transmissibility (this word means "dissemination power" or "spreadability" and is kept as is for contextual integrity).

Tradable Vehicle

This refers to companies that are highly bound to a certain technology and carry its technological narrative. Investors see them as explorers realizing the technology and buy into the 'technological narrative' by purchasing their stocks.

For example, Tesla emerged as a symbol of new energy vehicles, and Elon Musk, being a controversial figure, often attracts public attention. However, Tesla ultimately delivered on the promises in its story. But that wave of new energy vehicle manufacturing included not only Tesla but also a string of fleeting names like Fisker, Dyson, Bright, and Coda, all of whom carried this narrative and attracted some investors.

Generally, when there are too many of these vehicles and most lack actual performance support, relying solely on storytelling to drive valuations, the bubble will inflate further. During the Internet bubble, over 70% of more than 200 Internet companies had negative profits, which was already an extremely dangerous signal.

If we refine the above three points, we can gain some understanding of bubble identification. For instance, we can verify key points related to uncertainty, such as technological breakthroughs, production volumes, the formation of competitive barriers, and profit models. We can also assess whether the core narrative of a technology or company remains stable, gradually collapsing or becoming more robust, as well as the real performance of participating companies and the risk of cash flow disruptions.

Although these three points seem brief, they are quite complex. Therefore, it is still important to acknowledge one's own ignorance and refrain from investing in things one does not understand before gaining clarity, let alone following the crowd.