Robotic Dreams Blossom in Shenzhen, Pricing Power Thrives in Zhengzhou

![]() 12/04 2025

12/04 2025

![]() 533

533

The year 2025 is drawing to a close amidst unprecedented noise and intensity.

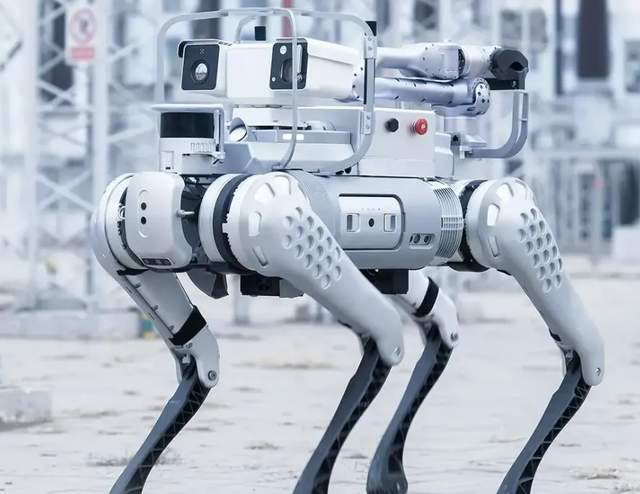

Over the past two days, the atmosphere in WeChat groups dedicated to robotics has grown exceedingly nuanced. On the surface, everyone is marveling at the launch video of Shenzhen’s Zhongqing T800, particularly its impressive aerial roundhouse kick. Yet, behind closed doors, at private gatherings, industry insiders discuss one topic with deep-seated anxiety: the starting price of 180,000 yuan.

If that price doesn't already pose a significant threat to traditional manufacturers, consider that Unitree Technology, known for its relentless price reductions, has already slashed the price of its G1 model to just 99,000 yuan.

This scenario is not only surreal but, I dare say, somewhat unsportsmanlike.

A year ago, humanoid robots were the million-yuan darlings of laboratories, untouchable treasures reserved for elite universities and research institutions. Today, their prices have plummeted to the level of a ride-hailing car—becoming mere industrial consumables.

This isn't just a discount; it's a halving, a crushing, bone-shattering price collapse.

Who's driving this change? The tech enthusiasts of Shenzhen’s Nanshan District? The scientists of Beijing’s Haidian? No.

If you limit your focus to Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen, you’ll never grasp the true nature of this battle. The real answer lies in China’s seemingly low-key yet fiercely competitive central industrial belt.

In previous articles, we discussed the speed of the Pearl River Delta and the precision of the Yangtze River Delta. In this piece, titled "The Cost War," we must shift our gaze to Zhengzhou, Wuhan, and Wuhu.

It is this central industrial corridor that is leveraging the same ruthless efficiency it applied to building iPhones and cars to drive robot prices to unprecedented lows.

Research and development may take place in Shenzhen, but the march towards affordability must head towards Zhengzhou.

To comprehend the brutality of this cost war, we must delve into the numbers. Once you see them, you’ll realize just how exorbitantly profitable—or desperate—the robot industry once was.

If you dissected a mainstream humanoid robot in 2023, you’d find a precision instrument built with gold.

Unfolding the bill of materials, three major cost drivers emerge: planetary roller screws, frameless torque motors, and harmonic reducers.

These three components alone account for 60% of the total cost.

Especially that unassuming screw—previously imported from Switzerland or Germany at exorbitant prices due to extreme precision requirements and low production volumes. A single screw cost 20,000 yuan, and a robot needed a dozen or more. Just purchasing the screws could cost as much as a compact car.

At that stage, everyone was hand-assembling prototypes in first-tier city offices. Engineers tinkered nervously, yield rates were abysmal, and supply chains were scattered like stars. Selling a robot for 500,000 yuan? That was charity—far from covering R&D costs.

But what Zhongqing T800 has accomplished this time truly captures the essence of the situation.

Its launch event took place in the glitzy surroundings of Shenzhen with futuristic PPTs, but its production base was毫不犹豫ly placed in Zhengzhou, Henan.

Shortly before the launch, Zhongqing announced a 200-acre manufacturing base in Zhengzhou, planning to produce 5,000 units annually.

Why Zhengzhou? Many assume it’s just about cheap land. But that’s a superficial view. Zhengzhou holds a trump card: the world’s most mature electronic contract manufacturing ecosystem. It’s home to Foxconn, hundreds of thousands of skilled workers accustomed to precision assembly, and a railway logistics network that spans the globe.

The industrial logic here is ruthless: the robot cost war is ultimately a scale war.

Shenzhen’s Nanshan District is ideal for innovation and prototyping—it’s where products are defined. But to mass-produce 180,000-yuan robots at iPhone-like scales, you must relocate.

You must go to regions with broader land, cheaper energy, and denser labor. Only there, on those roaring assembly lines, can you push the processing cost of each screw to its physical limits.

Shenzhen defines the product, but Zhengzhou determines affordability.

Here, the specialty isn’t spicy duck necks—it’s the dimensional reduction slaughter of automotive supply chains.

Beyond geographical advantages, the central industrial belt wields a true killer weapon, a blade that terrifies traditional robot companies: the automotive supply chain.

Unfolding China’s industrial map, you’ll see the central region isn’t just a transportation hub—it’s the heart of China’s automotive industry.

Wuhan is Dongfeng’s stronghold, Wuhu is Chery’s hometown, and Hefei is a new energy vehicle powerhouse. When these automotive giants start building robots, it’s a dimensional reduction slaughter for traditional robot makers.

The current landscape resembles barbarians at the gates: Dongfeng Motor (Wuhan) has announced its humanoid robots will start factory work in 2026. Chery (Wuhu) just showcased its Mojia robot, also aimed at mass production.

In the eyes of these central automakers, what is a robot? Forget any lofty talk of silicon-based life—to them, it’s just an electric vehicle with two legs.

Since it’s a vehicle, it must be built like one. All previous logic is discarded. Custom motors for robots? Expensive. Now? They just repurpose automotive-grade motors from production lines, leveraging annual production scales of millions to halve costs instantly.

No need to reinvent batteries. Zhongqing T800’s solid-state battery offers 4-5 hours of runtime—a technology originally developed by new energy automakers to cure “range anxiety,” now deployed in robots. This is technological spillover.

As for the torso, CNC milling is out. Tesla-inspired “one-piece die-casting” is in—a magnesium-aluminum alloy skeleton emerges in one go, skipping finishing altogether.

For those accustomed to producing at scale, reducing a 20,000-yuan imported screw to a 500-yuan domestic one is routine. Their specialty is transforming luxury into industrial goods.

When Zhongqing T800 employs aerospace-grade magnesium-aluminum alloy die-casting, its cold, metallic shell resembles Iron Man’s armor. But the cost logic behind it reeks of automotive pragmatism. This isn’t about creating billion-dollar superheroes—it’s about building two-legged cars.

Extreme frugality: Solving rich problems with poor methods.

If shifting the supply chain is a strategic move, then technical route selection reveals a uniquely Chinese factory-style cunning and pragmatism. To hit the 99,000-yuan price point, Chinese manufacturers have displayed astonishing calculation—even bordering on miserliness.

First, they slashed LiDAR. Early robots sport multiple laser LiDAR sensors on their heads for navigation. A single high-end LiDAR could exceed $1,000. But on Unitree’s G1, you’ll rarely find those expensive sensors. Instead, it uses cameras costing a few dollars each.

The logic is simple: as AI models (the “brains”) grow smarter, the demands on “eyes” diminish. Software can compensate for expensive hardware. Even with 2D images, algorithms can reconstruct 3D worlds. This cut alone shaves tens of thousands off costs.

Next, material substitution. Carbon fiber was once mandatory for lightness—a noble but costly choice. Now? Central factories say: engineering plastics (PEEK) or even modified nylon work fine. With proper structural design and topological optimization, plastics can bear hundreds of kilograms, survive drops, and cost just a hundred yuan to replace.

This makeshift pragmatism may sound unsophisticated, even crude, but it’s the core secret behind China’s ability to reduce high-tech to commodity prices. In business, “good enough” often trumps “perfect.”

The central region decides victory: robots become appliances.

180,000 yuan for the T800, 99,000 yuan for the G1. These numbers mark a turning point: robots are no longer celestial artworks but large-scale household appliances.

Recall: 99,000 yuan matches the price of a BYD Qin sedan; 180,000 yuan equals two years’ salary for a skilled worker (assuming no spending). When robot prices approach or fall below annual wages, the math for replacing humans finally works.

Previously, factory owners avoided robots due to cost and repair headaches. Now, Zhongqing claims total operating costs are one-third of human labor; Unitree says replacing a joint module costs just a few hundred yuan. If you’re a boss, what’s your choice?

The war’s conclusion will unfold in the central region.

The game is now open: the Pearl River Delta births the robots (innovation, prototyping, definition); the Yangtze River Delta refines them (control systems, materials, breakthroughs); the central industrial belt will flood the world with them.

Future robots will roll off central assembly lines like Zhengzhou-made iPhones or Wuhan-made cars, shipping globally.

They need no souls—just cheapness, durability, and abundance.

Finally

From the lights of Shenzhen Bay to the precision workshops of the Yangtze River Delta, culminating in the roaring assembly lines of the central region, we see a clear roadmap for China’s robot cost reduction. The West proposes concepts (Boston Dynamics, Tesla), while China’s central factories refine them into commodity-priced industrial goods.

As T800s are assembled in Zhengzhou factories and Dongfeng’s robots begin factory work in Wuhan, we know the era of mass commercialization has arrived.

The bodies are built, prices slashed. Now, only the hardest step remains: installing a true soul into these cheap, robust bodies. After all, a 99,000-yuan body paired with an AI-impaired brain remains just a large toy.

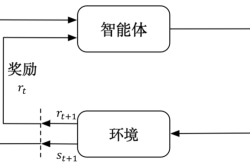

Next, we enter the war’s decisive phase—'The Intelligence War.' We’ll dissect the hype and truth behind large models, reinforcement learning, and embodied AI.