What Does the "Generalization Ability" Often Mentioned in Large Autonomous Driving Models Refer To?

![]() 12/10 2025

12/10 2025

![]() 499

499

When discussing large autonomous driving models, several evaluation dimensions frequently come up, such as perception accuracy, decision-making stability, system robustness, and whether the model possesses "generalization ability." Compared to easily quantifiable metrics like accuracy and latency, the term "generalization ability" appears more abstract and is often used vaguely.

It lacks intuitive evaluation criteria, yet it determines whether the model can truly transcend its training data and handle unknown situations on real roads. Clearly understanding what it refers to, why it is challenging, and how to evaluate it is the first step in grasping the capability boundaries of large autonomous driving models.

What is Generalization Ability?

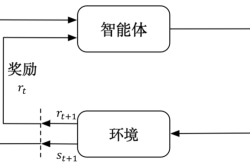

Generalization ability refers to whether a machine learning model can apply what it has learned during training to new, unseen situations. To illustrate with a simple example, training is akin to a teacher teaching a set of example problems, while generalization is the student's ability to solve new problems using the learned methods.

For autonomous driving, generalization ability means that the trained perception, prediction, and planning modules not only perform well under laboratory conditions but also remain reliable on real roads. Whether it's on daily streets or in scenarios not fully encountered during training, such as rainy days, nights, or construction zones, the system must continuously make reasonable and safe judgments and decisions. It is not a performance metric that can be measured by a single score but rather a comprehensive reflection of the stability and trustworthiness of the entire autonomous driving system in unknown environments and complex conditions.

Why Does Autonomous Driving Place Particular Emphasis on Generalization?

Unlike most pure vision or recognition tasks, autonomous driving bears responsibility for traffic safety. Data can never be exhaustive; there are countless roads worldwide, varying traffic habits across different countries, various weather and lighting combinations, temporary construction, and strange road signs, as well as random behaviors of drivers and pedestrians.

The samples encountered during training are limited, while real-world variations are far more complex. Scenarios such as children suddenly darting out from behind cars, cargo spills, reversed temporary signs, extreme rainstorms, or icy roads—"rare but dangerous" tail scenarios—rarely appear in training sets but have more severe consequences when they occur. If the model cannot generalize in these scenarios, it cannot be considered qualified for autonomous driving.

Besides safety reasons, generalization also determines the system's scalability and commercial deployment costs. Good generalization means that the same model can be reused in more cities and broader operational design domains (ODDs), saving costs associated with repeated data collection and labeling.

Why is Generalization So Difficult?

Generalization ability in large models has always been an important evaluation metric, but ensuring sufficient generalization is challenging. The training sets of large models and their actual deployment environments often do not follow the same distribution. A training set collected during the daytime, in clear weather, and in urban areas cannot guarantee performance at night, in rural areas, or in another city.

For large models, it is easy to "memorize" training samples without truly understanding the underlying patterns, a phenomenon known as overfitting. The model itself may be highly capable, but if the training data is not sufficiently diverse or the constraints are inappropriate, it may latch onto small features that only hold true in the training data as a basis for judgment. This approach may seem effective during training but fails when the environment or scenario changes, leading to a decline in model performance.

Autonomous driving is a multi-module, multi-sensor, and multi-task system where errors between perception, prediction, planning, and control can amplify. Sensors also have their weaknesses: cameras are limited in backlight or low-light conditions, radar lacks detail resolution, and LiDAR performance degrades in certain weather or when obstructed. The varying failure modes of different sensors make the behavior of large models in new environments even more unpredictable.

Additionally, an often-overlooked issue is whether the model is "accurately measured." Many times, people only focus on the average scores on validation sets or leaderboards. Some models may appear to perform well, but these numbers only reflect common scenarios and do not indicate how they will behave in rare, complex, or dangerous situations. Some truly risky scenarios may be precisely masked by average metrics.

At the same time, for autonomous driving to operate truly on the road, it must also meet legal and safety requirements. This means the system must not only perform well in most cases but also anticipate how to detect, monitor, and safely exit if the model makes errors in unfamiliar scenarios, rather than waiting for problems to occur before taking remedial action. The manifestation of these capabilities can all be attributed to the generalization ability of large models.

How to Improve the Generalization Ability of Large Models?

To truly enhance the generalization ability of large models, one cannot solely focus on data. While data is important, having a greater variety of data types is even more critical. In practical training, data needs to be collected under different cities, seasons, and road network structures, while also covering various camera and sensor configurations. Scenarios that are uncommon but prone to causing issues, such as rainy days, nights, construction zones, and temporary traffic signs, should also be included in the training process as much as possible. The role of data augmentation is not just to simply increase brightness or adjust contrast but to simulate variations that may be encountered in the real world in a targeted manner. When necessary, synthetic data can also be used to supplement scenarios that are difficult to collect in large quantities in reality.

To achieve these goals, the role of simulation becomes prominent. Through high-quality simulation, a large number of dangerous or extreme scenarios that are difficult to repeatedly collect in reality can be constructed, allowing large models to gain prior exposure. Of course, simulation cannot be haphazardly constructed. If the simulation environment differs too greatly from real roads, the large model will only learn the patterns of the virtual world and may encounter problems once deployed on real roads. Therefore, simulation needs to cover a variety of environmental changes and continuously use real data for calibration and correction, forming a closed loop that continuously aligns with the real world.

Many technical solutions also aim to make models more adaptable to new environments at the algorithmic level. For example, domain adaptation involves using a small portion of data from a new environment to make targeted adjustments to the model before formal deployment, allowing it to "acclimate to the new place." Domain generalization goes a step further, hoping that the model will not overly rely on a specific city or scenario during the training phase but instead learn more general judgment criteria. Transfer learning and meta-learning follow similar ideas: one brings general capabilities learned in an old environment to a new one, while the other enables the model to adapt more quickly to new scenarios.

Additionally, there are robust training methods that can make the model less sensitive to noise and perturbations. Confidence estimation and anomaly detection, on the other hand, expose uncertainties in a timely manner when the large model is "not very sure," preventing it from continuing to make overly aggressive judgments.

No single sensor is stable and reliable in all situations. To enhance the generalization ability of large models, the system's safety cannot be solely entrusted to a single perception source or model. Cameras, radar, LiDAR, positioning, and maps each have their advantages. By using them as complementary information sources and verifying each other through cross-validation and consistency checks, other channels can provide supplementary information when one sensor is affected. Through redundancy, the system can also gradually tighten its capabilities when uncertainty increases, transitioning from normal autonomous driving to a restricted mode, then to alerting for manual takeover, and finally executing a safe stop if necessary, rather than waiting for obvious errors to occur before reacting dramatically.

For the evaluation and verification of large models, one cannot simply look at "average performance" but must consider whether "scenarios are adequately covered." Before a vehicle is deployed on the road, there should be a comprehensive scenario library that clearly outlines which weather conditions, lighting conditions, intersection types, and sudden behaviors the system has covered. At the same time, pressure tests should be specifically conducted for rare but high-risk scenarios, rather than just looking at an overall accuracy rate. After the system goes live, it should not be left unattended; instead, continuous monitoring of actual performance should be carried out through log analysis, near-miss event replay, and other methods. Problems exposed during real-world operation should be reintroduced into the training process, forming a closed loop of continuous correction.

Final Remarks

When evaluating whether a large autonomous driving model is truly capable, one cannot merely look at how well it performs on a test set but also whether it can remain stable on real roads, in different cities, weather conditions, and with varying traffic participants. Generalization ability, in essence, evaluates whether the model has truly "learned to drive." Only large models that can still make reasonable and safe decisions in unseen scenarios have the potential to step out of the laboratory and be truly used on the road.

-- END --